The Break-Up of the Ksar: Settlement Change and Common Property Institutions on the Saharan Frontier Draft Paper Not for Citatio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF. Ksar Seghir 2500Ans D'échanges Inter-Civilisationnels En

Ksar Seghir 2500 ans d’échanges intercivilisationnels en Méditerranée • Première Edition : Institut des Etudes Hispanos-Lusophones. 2012 • Coordination éditoriale : Fatiha BENLABBAH et Abdelatif EL BOUDJAY • I.S.B.N : 978-9954-22-922-4 • Dépôt Légal: 2012 MO 1598 Tous droits réservés Sommaire SOMMAIRE • Préfaces 5 • Présentation 9 • Abdelaziz EL KHAYARI , Aomar AKERRAZ 11 Nouvelles données archéologiques sur l’occupation de la basse vallée de Ksar de la période tardo-antique au haut Moyen-âge • Tarik MOUJOUD 35 Ksar-Seghir d’après les sources médiévales d’histoire et de géographie • Patrice CRESSIER 61 Al-Qasr al-Saghîr, ville ronde • Jorge CORREIA 91 Ksar Seghir : Apports sur l’état de l’art et révisoin critique • Abdelatif ELBOUDJAY 107 La mise en valeur du site archéologique de Ksar Seghir Bilan et perspectives 155 عبد الهادي التازي • مدينة الق�رص ال�صغري من خﻻل التاريخ الدويل للمغرب Préfaces PREFACES e patrimoine archéologique marocain, outre qu’il contribue à mieux Lconnaître l’histoire de notre pays, il est aussi une source inépuisable et porteuse de richesse et un outil de développement par excellence. A travers le territoire du Maroc s’éparpillent une multitude de sites archéologiques allant du mineur au majeur. Citons entre autres les célèbres grottes préhistoriques de Casablanca, le singulier cromlech de Mzora, les villes antiques de Volubilis, de Lixus, de Banasa, de Tamuda et de Zilil, les sites archéologies médiévaux de Basra, Sijilmassa, Ghassasa, Mazemma, Aghmat, Tamdoult et Ksar Seghir objet de cet important colloque. Le site archéologique de Ksar Seghir est fameux par son évolution historique, par sa situation géographique et par son urbanisme particulier. -

Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco

sustainability Article Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco Teresa Gil-Piqueras * and Pablo Rodríguez-Navarro Centro de Investigación en Arquitectura, Patrimonio y Gestión para el Desarrollo Sostenible–PEGASO, Universitat Politècnica de València, Cno. de Vera, s/n, 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article is presented after ten years of research on the earthen architecture of southeast- ern Morocco, more specifically that of the natural axis connecting the cities of Midelt and Er-Rachidia, located North and South of the Moroccan northern High Atlas. The typology studied is called ksar (ksour, pl.). Throughout various research projects, we have been able to explore this territory, documenting in field sheets the characteristics of a total of 30 ksour in the Outat valley, 20 in the mountain range and 53 in the Mdagra oasis. The objective of the present work is to analyze, through qualitative and quantitative data, the main characteristics of this vernacular architecture as a perfect example of an environmentally respectful habitat, obtaining concrete data on its traditional character and its sustainability. The methodology followed is based on case studies and, as a result, we have obtained a typological classification of the ksour of this region and their relationship with the territory, as well as the social, functional, defensive, productive, and building characteristics that define them. Knowing and puttin in value this vernacular heritage is the first step towards protecting it and to show our commitment to future generations. Keywords: ksar; vernacular architecture; rammed earth; Morocco; typologies; oasis; High Atlas; sustainable traditional architecture Citation: Gil-Piqueras, T.; Rodríguez-Navarro, P. -

1 Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia

Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia: Late Iron Age – Second Century AD Jonathan Wynne Rees Thesis submitted in requirement of fulfilments for the degree of Ph.D. in Archaeology, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London University of London 2012 1 I, Jonathan Wynne Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changes which occurred in the cultural landscapes of northwest Iberia, between the end of the Iron Age and the consolidation of the region by both the native elite and imperial authorities during the early Roman empire. As a means to analyse the impact of Roman power on the native peoples of northwest Iberia five study areas in northern Portugal were chosen, which stretch from the mountainous region of Trás-os-Montes near the modern-day Spanish border, moving west to the Tâmega Valley and the Atlantic coastal area. The divergent physical environments, different social practices and political affinities which these diverse regions offer, coupled with differing levels of contact with the Roman world, form the basis for a comparative examination of the area. In seeking to analyse the transformations which took place between the Late pre-Roman Iron Age and the early Roman period historical, archaeological and anthropological approaches from within Iberian academia and beyond were analysed. From these debates, three key questions were formulated, focusing on -

English/French

World Heritage 36 COM WHC-12/36.COM/8D Paris, 1 June 2012 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-sixth Session Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 24 June – 6 July 2012 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8D: Clarifications of property boundaries and areas by States Parties in response to the Retrospective Inventory SUMMARY This document refers to the results of the Retrospective Inventory of nomination files of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. To date, seventy States Parties have responded to the letters sent following the review of the individual files, in order to clarify the original intention of their nominations (or to submit appropriate cartographic documentation) for two hundred fifty-three World Heritage properties. This document presents fifty-five boundary clarifications received from twenty-five States Parties, as an answer to the Retrospective Inventory. Draft Decision: 36 COM 8D, see Point IV I. The Retrospective Inventory 1. The Retrospective Inventory, an in-depth examination of the Nomination dossiers available at the World Heritage Centre, ICOMOS and IUCN, was initiated in 2004, in parallel with the launching of the Periodic Reporting exercise in Europe, involving European properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. The same year, the Retrospective Inventory was endorsed by the World Heritage Committee at its 7th extraordinary session (UNESCO, 2004; see Decision 7 EXT.COM 7.1). -

Revisiting Colonized Morocco: New Approaches and Recent Trends

Vendredi 5 juillet 2019 - Première session Atelier 32 Salle : 11 Revisiting Colonized Morocco: New Approaches and Recent Trends In the field of Modern North African studies in the last decades, the history of colonized Morocco has suffered from the boom of research dealing with Algeria, especially in the French academia; and to add to that, Spanish colonialism in the Northern zone occupies a marginal position in the field of Moroccan studies. A series of recent works tend to make this assertion evolve: this interdisciplinary panel aims to make new trends visible and to create an international space for reflection on Moroccan history in connexion to the Spanish protectorate and its legacies. The communications will focus on the colonial and postcolonial history of Spanish colonialism in Morocco, with a set of questions linked to its distinctive features, peculiarities and long-term consequences in the global history of Modern North Africa. Moroccan Nationalism in the Spanish Protectorate is still underestimated while it proved crucial for Moroccan national emancipation. Its significance in the history of the national movement needs to be reassessed, as a “hub of transnational anti-colonial activism” (Stenner). Spanish colonial administration, while presenting itself as liberal and more open-minded than its French neighbour, even playing on the sense of a supposed “Hispano-Arab fraternity”, proved ambivalent. The policy towards the press published in Arabic is a relevant case study in this framework, as it navigated between tolerance and repression (Velasco de Castro). The Spanish colonial policies regarding colonized populations, and notably the Jewish minority, is also an interesting point to study as “Hispano-Arab fraternity” rhetoric coexisted with “philo-Sephardism”. -

Er-Rachidia, Morocco): an Inventory

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLIV-M-1-2020, 2020 HERITAGE2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra) International Conference, 9–12 September 2020, Valencia, Spain THE KSOUR OF THE MDAGRA OASIS (ER-RACHIDIA, MOROCCO): AN INVENTORY T. Gil-Piqueras 1, 2, *, P. Rodríguez-Navarro 1, 2 1 Dept. Architectural Graphic Expression, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain - ([email protected],es, [email protected]) 2 Research Centre PEGASO, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain Commission II - WG II/8 KEY WORDS: Mdagra, Ksar, Fortified Architecture, Vernacular Architecture, Rammed Earth, Pre-Saharan Oasis, Morocco ABSTRACT: The Mdagra Oasis is located in the province of Er-Rachidia, in southern Morocco. The objective of this contribution is to present an unparalleled inventory of the ksour existing in that oasis, the result of several years of study and field exploration. During the Saadi period (16th century), this area of the Ziz basin was a compulsory stop for traders on the route of caravans crossing the High Atlas. Later, during the Alauita period, the area was consolidated, and for more than 400 years many important cities were constructed using rammed earth, as Ksar es Souq or Sidi Bou Abdellah Ksar. This is how the oasis came to have an important community integrated by Berbers, Arabs and Jews. Today, most of the oasis’ ksour are abandoned for different reasons and remain in a state of advanced ruin. Through fieldwork, we have been able to identify, record, analyze and classify 53 earthen human settlements, providing an unprecedented study of all of them. Subsequently, a first typological classification was proposed based on aspects such as the implementation in the territory, the external morphology, the urban organization, or the occupation area. -

Tunisie Tunisia

TUNISIETUNISIA ROUTEUMAYYAD DES OMEYYADES ROUTE Umayyad Route TUNISIA UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route Tunisia. Umayyad Route 1st Edition, 2016 Copyright …… Index Edition Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí Introduction Texts Mohamed Lamine Chaabani (secrétaire général de l’Association Liaisons Méditerranéennes); Mustapha Ben Soyah; Office National du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT) Umayyad Project (ENPI) 5 Photographs Office National du Tourisme Tunisien; Fundación Pública Andaluza El legado andalusí; Tunisia. History and heritage 7 Association Environnement et Patrimoine d’El Jem; Inmaculada Cortés; Carmen Pozuelo; Shutterstock Umayyad and Modern Arab Food. Graphic Design, layout and maps José Manuel Vargas Diosayuda. Diseño Editorial Gastronomy in Tunis 25 Printing XXXXXX Itinerary Free distribution ISBN Kairouan 34 978-84-96395-84-8 El Jem 50 Legal Deposit Number XXXXX-2016 Monastir 60 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, nor transmitted or recorded by any information Sousse 74 retrieval system in any form or by any means, either mechanical, photochemical, electronic, photocopying or otherwise without written permission of the editors. Zaghouan 88 © of the edition: Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí. Tunis 102 © of texts: their authors © of pictures: their authors Bibliography 138 The Umayyad Route is a project funded by the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) and led by the Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí. It gathers a network of partners in seven countries -

Image of the Noble Abdelmelec in Peele's the Battle of Alcazar

English Language and Literature Studies; Vol. 6, No. 2; 2016 ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Image of the Noble Abdelmelec in Peele’s The Battle of Alcazar Fahd Mohammed Taleb Al-Olaqi1 1 Department of English & Translation, University of Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Fahd Mohammed Taleb Al-Olaqi, Department of English & Translation, Faculty of Science and Arts - Khulais, University of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. P. O. B. 355, Khulais 21921, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 30, 2016 Accepted: April 18, 2016 Online Published: April 28, 2016 doi:10.5539/ells.v6n2p79 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ells.v6n2p79 Abstract There is no ambiguity about the attractiveness of the Moors and Barbary in Elizabethan Drama. Peele’s The Battle of Alcazar is a historical show in Barbary. Hence, the study traces several chronological texts under which depictions of Moors of Barbary were produced about the early modern stage in England. The entire image of Muslim Moors is being transmitted in the Early Modern media as sexually immodest, tyrannical towards womanhood and brutal that is as generated from the initial encounters between Europeans and Arabs from North Africa in the sixteenth century and turn out to be progressively associated in both fictitious and realistic literatures during the Renaissance period. Some Moors are depicted in such a noble manner especially through this drama that has made them as if it was being lately introduced to the English public like Muly (Note 1) Abdelmelec. -

07.Tunez.Recorrido Vii

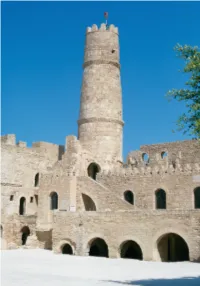

ITINERARY VII The Ribat Towns Mourad Rammah VII.1 MONASTIR VII.1.a The Ribat VII.1.b Sidi al-Ghedamsi Ribat (option) VII.2 LEMTA VII.2.a The Ribat (option) VII.3 SOUSSE VII.3.a The Ribat VII.3.b The Great Mosque VII.3.c Al-Zaqqaq Madrasa VII.3.d Qubba bin al-Qhawi VII.3.e Sidi ‘Ali ‘Ammar Mosque VII.3.f Buftata Mosque VII.3.g The Kasbah and the Ramparts The Ribat, Monastir. 185 ITINERARY VII The Ribat Towns Monastir The assaults of the Byzantine fleet along the itary and religious purpose were reflected coast following the Muslim Conquest in their robust and austere architecture, forced the Ifriqiyans to build a continuous characterised by the use of stone and vaults line of defence consisting of fortresses made of rubble and the banishment of called ribats. They rose along the coastline wood coverings and light structures. This from Tangier to Alexandria and communi- type of architecture spread across the cated via the use of fires lit up at the top of whole of the Tunisian Sahel, and Sousse and the towers. The ribats served as a refuge for Monastir became the two ribat-towns par the inhabitants of the surrounding coun- excellence. tryside and were lived in by warrior Whilst all making reference to the same monks. The prolonged stays and visits of school of architecture, they nevertheless the most illustrious Ifriqiyan scholars, each underwent a slightly different evolu- jurisconsults and ascetics reinforced the tion. Sousse became in the 3rd/9th century spiritual prestige of these buildings, trans- the headquarters of the Aghlabid fleet and forming them into veritable monastery- the most important naval military base, fortresses and centres of learning that which was involved in the Conquest of Sici- transmitted Arab-Muslim culture along the ly in 211/827, as well as being the crucible north coast of North Africa. -

CHAIN Las Otras Orillas

CHAIN Cultural Heritage Activities and Institutes Network Las otras orillas Sevilla and other places, 16-25/11/17 Enrique Simonet, Terrazas de Tánger (1914) The course is part of the EU Erasmus+ teacher staff mobility programme and organised by the CHAIN foundation, Netherlands A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa, Born in the West, far from the land of palms. I said to it: how like me you are, far a way and in exile, In long separation from family and friends. You have sprung from soil in which you are a stranger; And I, like you, am far from home. Contents Las otras orillas - a course story line ........................................................................................... 5 San Salvador (in Sevilla) ........................................................................................................... 8 Seville: The Cathedral St. Mary of the See ................................................................................. 10 Seville: Mudéjar Style ............................................................................................................. 12 Seville: How to decipher the hidden language of monuments' decoration ....................................... 14 Córdoba: A Muslim City on the remains of a Roman Colony ......................................................... 17 The Mezquita in Cordoba ......................................................................................................... 19 Streets of Córdoba ................................................................................................................ -

THE BATTLE of ALCAZAR by George Peele

ElizabethanDrama.org presents the Annotated Popular Edition of THE BATTLE OF ALCAZAR by George Peele First Published 1594 Featuring complete and easy-to-read annotations. Annotations and notes © Copyright Peter Lukacs and ElizabethanDrama.org, 2019. This annotated play may be freely copied and distributed. 1 THE BATTLE OF ALCAZAR BY GEORGE PEELE First Published 1594 The Battell of Alcazar, fovght in Barbarie, betweene Sebastian king of Portugall, and Abdelmelec king of Marocco. With the death of Captaine Stukeley. An it was sundrie times plaid by the Lord high Admirall his seruants. Imprinted at London by Edward Allde for Richard Bankworth, and are to be solde at his shoppe in Pauls Churchyard at the signe of the Sunne. 1 5 9 4. DRAMATIS PERSONS. Introduction to the Play The Usurper and His Supporters: In The Battle of Alcazar, George Peele recounts one of the oddest military expeditions in European history, the The Moor, Muly Mahamet. failed 1578 invasion of Morocco by a ragtag army led by Muly Mahamet, his son. Portugal's King Sebastian. Sebastian was a young man with Calipolis, wife of the Moor. a dream of bringing a Crusade into Africa, but whose com- Pisano, a Captain of the Moor. bination of obstinacy and lack of experience produced a national catastrophe, matched in its results perhaps only The Rightful Ruler and His Supporters: by the Scottish defeat at Flodden. No one can pretend that Alcazar will ever rank among Abdelmelec, uncle of the Moor, and rightful ruler the greatest of Elizabethan dramas, but the story is intriguing of Morocco. -

Ciudades Imperiales Y Paisajes De Marruecos

CIUDADES IMPERIALES Y PAISAJES DE PRECIO ORIENTATIVO 660 € MARRUECOS Marrakech, Casablanca, Rabat, Meknes, Fez, Ifran, Errachidia, Erfoud, Gargantas del Todra, Ouarzazate y Ait Ben Hadou. 8 días / 7 noches. Viajar por las ciudades imperiales supone descubrir su historia milenaria y sus monumentos, el legado de gloriosas dinastías pasadas. Día 1 Ciudad de Origen - Marrakech (Media pensión) puertas doradas del Palacio Real. Visitaremos la antigua Vuelo de salida a la ciudad de Marrakech. Traslado al Medina con su Medersa de Bou Anania, la fuente Nej- hotel. Cena y alojamiento. jarine, una de las más bellas de la medina, la Mezquita Karaouine que alberga uno de los principales centros Día 2 Marrakech - Casablanca (Media pensión) culturales del Islam y es la sede de la universidad de Fez, Desayuno en el hotel. Visita de la ciudad de Marrakech de y el Mausoleo de Moulay Idriss. Nos detendremos en SERVICIOS INCLUIDOS · Vuelos en línea regular, clase turista. medio día. La visita comienza por los Jardines de la el famoso barrio de los curtidores, único en el mundo. · Compensación huella de CO2 de todos los vuelos. Menara en cuyo centro se encuentra un estanque del Almuerzo libre antes de continuar nuestra visita por esta · Alojamiento en hoteles previstos (o similares), en Siglo XII. Encaminaremos nuestros pasos hacia el majes- bellísima ciudad con sus barrios artesanos divididos por régimen de media pensión (sin bebidas), excepto en tuoso minarete de la Kutubia. Continuamos visitando el gremios. Cena y alojamiento. categoría A. Palacio de la Bahía, la farmacia Berebere y los zocos. La · Salida en regular con chofer y guías locales en español visita termina en la Plaza de Jemaa el Fna, declarada Patri- Día 5 Fez - Ifran - Midelt - Errachidia - Erfoud en Marrakech.