The University of Michigan a ,,,, Transportation Research Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizational Structure General Meetingofstockholders President Andc.E.O

64 Organizational Structure As of July 1, 2010 General Meeting of Stockholders Textile Material & Fabric Division Textile Material & Fabric Department Apparel Division Fabric & Apparel Department Brand Marketing Division 1 Apparel Department 1 Operational Structure Brand Marketing Division 2 Apparel Department 2 Planning & Administration Department Board of Corporate Auditors, Textile Company Brand Marketing Department 1 Affiliate Administration Department Brand Marketing Department 2 Corporate Auditors Headquarters Management Committee IT Business Development Department Brand Marketing Department 3 Industrial Textile & Lifestyle Department Chief Financial Officer CFO Office Marine Department Plant & Project Department No. 1 Investor Relations Department Machinery Company Plant Project & Marine Division Plant & Project Department No. 2 Corporate Auditors’ Office Automobile & Construction Machinery Division Automobile Department No. 1 Group Accounting Support & IFRS Office Planning & Administration Department Automobile Department No. 2 Chief Compliance Officer Affiliate Administration Department Automobile Business Promotion Department Isuzu Business Department Chief Information Officer Construction Machinery Department Audit Division ICT, Aerospace & Information Technology Business Department Board of Directors Electronics Company ICT & Media Division Media & Internet Business Department Secretariat Aerospace & Industrial Systems Division Mobile Network Business Department Planning & Administration Department Aerospace & Defense Department -

The Automobile in Japan

International and Japanese Studies Symposium The Automobile in Japan Stewart Lone, Associate Professor of East Asian History, Australian Defence Force Academy, Canberra Japan and the Age of Speed: Urban Society and the Automobile, 1925-30 p.1 Christopher Madeley, Chaucer College, Canterbury Kaishinsha, DAT, Nissan and the British Motor Vehicle Industry p.15 The Suntory Centre Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines London School of Economics and Political Science Discussion Paper Houghton Street No. IS/05/494 London WC2A 2AE July 2005 Tel: 020-7955-6699 Preface A symposium was held in the Michio Morishima room at STICERD on 7 April 2005 to discuss aspects of the motor industry in Japan. Stewart Lone discussed the impact which the introduction of the motor car had on Japan’s urban society in the 1920s, especially in the neighbourhood of the city of Kyoto. By way of contrast, Christopher Madeley traced the relationship between Nissan (and its predecessors) and the British motor industry, starting with the construction of the first cars in 1912 by the Kaishinsha Company, using chassis imported from Swift of Coventry. July 2005 Abstracts Lone: The 1920s saw the emergence in Kansai of modern industrial urban living with the development of the underground, air services; wireless telephones, super express trains etc. Automobiles dominated major streets from the early 1920s in the new Age of Speed. Using Kyoto city as an example, the article covers automobile advertising, procedures for taxis, buses and cars and traffic safety and regulation. Madeley: Nissan Motor Company had a longer connection with the British industry than any other Japanese vehicle manufacturer. -

Teaching the Trade War

s the table below hows, the United States has an enor mous bi lateral merchandise Lrade deficit with Japan. Much of the deficit reflect:.. the fac1 that the United State:-. tend:, to cxporl raw materials anJ a few military goud-, 10 Japan. whi le importing large amount:- or· manufactured items. The deficit in automobile vehicle:-. parts. and engines alone i~ equal 10 about 577c uf the total U.S.-Jupan trade deficit. Thar defrcir is in turn equal to PART 1 WITH ELLEN FROST roughly 43 % of the total U.S. trade deficit. P ETER Efforts LO lower the U.S. deficit include Prel-iiclenL Nixon·s threat to Let's take automobiles first. When Japa invoke the Trading with the Enemy act Lo gel Prime Minister Tanaka to ~el nese claim that U.S. auto makers can't sell ··voluntary .. textile quotn1- in 1968. the 1971 Smith:-.onian Agreement whid1 cars in Japan because they have not made allowed the value of the yen to floai upwards, a 1981 agreement 10 lim it (until recently) either right-hand drive cars Japane,e automobile import:-. the MOSS (Market Oriented Sector Specific l or cars at the low horsepower level (under 2,000 cc) that constitute 80% of the Japa talks begun in 1985 to olvc specilil: trade problem:,. the 1986 Semicon hese market, don't they have a point? ductor Trade Agrccmem wherein the Japanese government stateJ privately Eu.EN that it ·'expects'' the U.S. market share to reach 20%. the SIi (Structural The primary issue is not engine size or hnpediment Initiative) of 1988 under which Japan pledged lo deregulate steering wheels. -

A HISTORY of JAPAN's GOVERNMENT-BUSINESS RELATIONSHIP the Passenger Car Industry CENTER for JAPANESE STUDIES the UNIVERSITY of MICHIGAN

A HISTORY OF JAPAN'S GOVERNMENT-BUSINESS RELATIONSHIP The Passenger Car Industry CENTER FOR JAPANESE STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN MICHIGAN PAPERS IN JAPANESE STUDIES No. 20 A HISTORY OF JAPAN'S GOVERNMENT-BUSINESS RELATIONSHIP The Passenger Car Industry by PHYLLIS A. GENTHER Ann Arbor Center for Japanese Studies The University of Michigan 1990 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 1990 Center for Japanese Studies The University of Michigan 108 Lane Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1290 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Genther, Phyllis Ann. A history of Japan's government-business relationship: the passenger car industry / by Phyllis A. Genther. p. x, 242. cm. 23 — (Michigan Papers in Japanese Studies : no 20) Thesis (doctoral)—George Washington University. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-939512-40-8 1. Automobile Industry and trade—Government policy—Japan—History. I. Title. II. Series. HD9710.J32G46 1990 338.4'76292'0952-dc20 89-77218 CIP Index: AEIOU, Inc. oo Printed in the United States ISBN 978-0-939512-40-9 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12807-5 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90207-1 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ CONTENTS PREFACE ix CHAPTER 1: GOVERNMENT-BUSINESS RELATIONSHIPS IN GLOBAL COMPETITION 1 The Automobile Industry 2 Perspectives on Government-Business Relationships -

Passenger Cars

Passenger Cars Overall Trends cover, and the EU as a whole achieved a rate of 103.9%. 1 Introduction The increase in sales in Japan brought a slight produc- In 2014, the recovery of the European and U.S. mar- tion increase, bringing the rate to 101.1%. The vigorous kets, the ongoing, if slower, growth of the Chinese mar- U.S. market sustained high production levels, but as the ket, and the expansion of the market in ASEAN nations demand centered on SUVs, passenger car production (except Thailand), Central Europe and the Middle and dropped to 97.4% (Table 1). Near East led to worldwide sales of 60.88 million vehicles The ranking for passenger car production by manufac- in the 49 main countries, representing 103% of the previ- turing country remains unchanged from last year, with ous year. While recovery and growth in individual coun- the Hyundai Group in first place, followed by Toyota, tries were clearly affected by events such as the Ukrai- the Volkswagen Group, BMW and Daimler, in second to nian crisis and the drop in crude oil prices, the global fifth place. Honda, which increased production in Japan, market as a whole continued to grow. rose to 6th place, while Mazda, which reduced domestic In the 2014 Japanese market, last minute demand production, dropped to 7th place. Honda, Suzuki, Fuji between January and March ahead of the raising of Heavy Industries and Mitsubishi increased production in the consumption tax in April, as well as the remaining Japan, while Toyota, Mazda and Nissan reduced it, and backlog of orders in April and later, boosted sales of pas- senger cars, bringing them over 4.6 million vehicles for Table 1 Passenger car production in leading manufacturing countries the first time in eight years. -

Fact Book 2016

SUBARU CORPORATION Fact Book 2016 Corporate Communications Dept. SUBARU Fact book 2016 54 Corporate Information Contents ※Click title to jump to the details. Corporate Information 1 Profile 3 Aerospace Company 2 Mid-term Management Vision 4 1 Aircraft Production 31 3 Board Directors / Executive Officers 7 4 Organization 9 5 Domestic facilities 10 Industrial Products Company 6 Main Affiliates (Japan) 11 ※The Industrial Products Company will be integrated with the Subaru Automotive Business with effect from October 1, 2016. 7 Main Affiliates (Overseas) 12 1 Sales of General-Purpose Engines 32 8 Employees 13 2 Production of General-Purpose Engines 9 Facilities 14 (including on-board use) 32 3 Product Lineup 33 4 Specified dealers of Subaru products 33 Business Results 1 Consolidated Sales and Profits 15 2 Non-Consolidated Sales and Profits 16 Eco Technologies Company 34 3 Capital Expenditures, Depreciation and ※Eco Technology Company was discontinued in March R&D Expenses 16 2013. Share Information History 1 Share Information 17 1 Pre-Fuji Heavy Industries 35 2 Fuji Heavy Industries 36 NOTES: Automotive Business *The fiscal years stated in the Fact Book begin on April 1 of the previous year and end on March 31 of the year 1 Production 18 indicated. 2 Sales 20 3 Export 21 4 Brand Statement and Core Technologies 22 5 Product Lineup 25 6 Domestic sales agents 29 7 Overseas market overview 30 SUBARU Fact book 2016 2 Corporate Information 1 Profile Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd.(FHI) Name *FHI will change its company name to “SUBARU CORPORATION” with effect from April 1, 2017. -

Health Newsletter 11 February 99

BDA Business Development Asia ASIA IS A BUSINESS IMPERATIVE… NOW MORE THAN EVER ASIAN AUTOMOTIVE NEWSLETTER Issue 34, December 2002 A bimonthly newsletter of developments in the auto and auto components markets CONTENTS CHINA INTRODUCTION ................................................ 1 China will allow car companies to set up financing CHINA ............................................................... 1 units, making it possible for Ford, GM, Honda, Volkswagen AG, and other automakers to offer loans INDIA ................................................................ 3 direct to Chinese consumers for the first time. Chinese INDONESIA ...................................................... 4 and foreign companies with RMB8bn (US$967m) or JAPAN .............................................................. 4 more in total assets, a capital base of at least KOREA ............................................................. 4 RMB500m (US$60m) and a capital adequacy ratio of MALAYSIA ........................................................ 5 at least 10% can apply to set up financing businesses PHILIPPINES .................................................... 5 under a draft proposal. Auto financing ventures will be TAIWAN ............................................................ 5 allowed to issue bonds, borrow from banks with THAILAND ......................................................... 5 guarantees, accept deposits from shareholders and vehicle buyers, and offer car loans and leasing services. (October 8, 2002) INTRODUCTION -

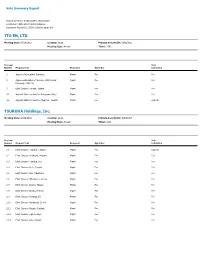

Vote Summary Report

Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 07/01/2019 to 06/30/2020 Location(s): State Street Global Advisors Institution Account(s): SPDR Solactive Japan ETF ITO EN, LTD. Meeting Date: 07/24/2019 Country: Japan Primary Security ID: J25027103 Meeting Type: Annual Ticker: 2593 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Accounting Transfers Mgmt For For 2 Approve Allocation of Income, With a Final Mgmt For For Dividend of JPY 20 3 Elect Director Tanaka, Yutaka Mgmt For For 4.1 Appoint Statutory Auditor Nakagomi, Shuji Mgmt For For 4.2 Appoint Statutory Auditor Miyajima, Takashi Mgmt For Against TSURUHA Holdings, Inc. Meeting Date: 08/09/2019 Country: Japan Primary Security ID: J9348C105 Meeting Type: Annual Ticker: 3391 Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Proponent Mgmt Rec Instruction 1.1 Elect Director Tsuruha, Tatsuru Mgmt For Against 1.2 Elect Director Horikawa, Masashi Mgmt For For 1.3 Elect Director Tsuruha, Jun Mgmt For For 1.4 Elect Director Goto, Teruaki Mgmt For For 1.5 Elect Director Abe, Mitsunobu Mgmt For For 1.6 Elect Director Mitsuhashi, Shinya Mgmt For For 1.7 Elect Director Ogawa, Hisaya Mgmt For For 1.8 Elect Director Okada, Motoya Mgmt For For 1.9 Elect Director Yamada, Eiji Mgmt For For 1.10 Elect Director Murakami, Shoichi Mgmt For For 1.11 Elect Director Atsumi, Fumiaki Mgmt For For 1.12 Elect Director Fujii, Fumiyo Mgmt For For 1.13 Elect Director Sato, Harumi Mgmt For For Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 07/01/2019 to 06/30/2020 Location(s): State Street Global Advisors Institution Account(s): SPDR Solactive Japan ETF TSURUHA Holdings, Inc. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74- 21,688

INFORMATION T O USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced t e c h means to p H o to g ra p h and reproduce this document have been used, the quai**y is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation1 of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns whic^* may appear on t h i s reproduction. 1. The sign or "targ et" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed i s "Missing Page(s)"- If it was possible to obtain the missing Page(s) or se c tio n , they are spliced i n to the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting Thru an image and duplicating adjacent Pagesto insure V o u complete c o n tin u ity . 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication That the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during e x p o su re and thus cau se a blurred image. You will find a good image of -c n e page in the a d ja c e n t frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being Photographed the photographer- followed a definite method in "sectioning" t h e material. It is custom ary to begin photoing at the upper •eft hand corr»®r of a lar9e sheet an d to continue photoing from left to fight in equal sections with a s m a l l overlap. -

Student Formula Japan Formula SAE

2018 ® Series 2018 Student Formula Japan Formula SAE 2017 Student Formula Japan Competition Winner Kyoto Institute of Technology 2018 Monozukuri Design Competition Since 2003 Student Formula JapanOfficial Program 2017 Student Formula Japan Spirit of Excellence Award for EV class Nagoya University EV 2018. Ogasayama Sports Park - ECOPA - 9/4TUE 8SAT Organizer Contents Message of Congratulations/President’s Message Awards ����������������������������������������������� 8 ���������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Organizer/Support/Committee Members ����� 9 Outline of Events�������������������������� 2 Team Information (Vehicle Specifications) ������������������������������������������������ Registered Teams ��������������������� 3 10 ~ 21 Schedule of Events ����������������� 4 Team Information (Members and Sponsors) �����������������������������������������������22 ~ 00 Sponsors ������������������������������� 5~6 Notices ���������������������������������������������� 7 Message of Congratulations/President’s Message Celebrating 2018 Student Formula Japan I would like to extend my heartfelt congratulations on the occasion of the 16th Student Formula Japan. As innovation progresses at a breakneck pace and technology makes bewildering advances, it is necessary to nurture the talent to spur the structural industrial reforms that will tie technological break- throughs such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data, or the Internet of things (IoT) into the fabric of so- ciety and move us closer to the fourth industrial revolution -

Annual Report 2006

Annual Report 2006 KEY FIGURES VOLKSWAGEN GROUP Volume Data 2006 2005 % Vehicle sales (units) 5,720,096 5,192,576 + 10.2 Production (units) 5,659,578 5,219,478 + 8.4 Employees at Dec. 31 324,875 344,902 – 5.8 Financial Data (IFRSs), € million 2006 20051] % Sales revenue 104,875 93,996 + 11.6 Operating profit before special items 4,383 2,889 + 51.7 Special items 2,374 351 x Operating profit 2,009 2,538 – 20.8 Profit before tax from continuing operations 1,793 1,621 + 10.6 Profit from continuing operations 1,955 1,050 + 86.2 Profit from discontinued operations 795 70 x Profit after tax 2,750 1,120 + 145.4 Cash flows from operating activities 14,470 10,709 + 35.1 Cash flows from investing activities 11,911 10,365 + 14.9 Automotive Division2] Cash flows from operating activities 11,745 8,112 + 44.8 Cash flows from investing activities 6,114 5,721 + 6.9 of which: investments in property, plant and equipment 3,644 4,316 – 15.6 as a percentage of sales revenue 3.8 5.0 capitalized development costs 1,478 1,432 + 3.2 as a percentage of sales revenue 1.5 1.7 Net cash flow 5,631 2,391 + 135.5 Net liquidity at Dec. 31 7,133 706 x Return ratios in % 2006 20051] Return on sales before tax (continuing operations) 1.7 1.7 Return on investment after tax (Automotive Division) 2.0 2.4 Return on equity before tax (Financial Services Division)3] 16.9 18.2 1] Restated. -

Formula SAE Japan 2019

学生Formula_日本大会2019第17回_A4_表_英.ai 2019 Formula SAE Japan Formula SAE® Series 2018 Competition Winner Osaka University 2019 Monozukuri Design Competition Since 2003 Formula SAE Japan 2018 Spirit of Excellence Award for EV Class Nagoya University EV ICV & EV Class 2019 8.27TUE 31SAT Ogasayama Sports Park - ECOPA - Organizer CONTENTS Message of Congratulations/President’s Message Awards ����������������������������������������������� 8 ���������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Organizer/Support/Committee Members ����� 9 About Formula SAE Japan ���� 2 Team Information (Vehicle Specifications) Registered Teams ��������������������� 3 ������������������������������������������������ 10 ~ 19 Schedule of Events ����������������� 4 Team Information (Members and Sponsors) �����������������������������������������������20 ~ 44 Sponsors ������������������������������� 5~6 Notices ���������������������������������������������� 7 OutlineOutline of Events of Events OutlineOutline of Events of Events 1. Purpose of Competition Outline of Events Outline To developof Events human resources that, through the support of government, industry, Aboutand academia, Formula will contribute SAEto the development Japan and promotion of both automobile 1.technology Purpose and of industry Competition by having the students play the main role in planning, designing, and constructing an automobile on their own in a competition of comprehensive To develop human monozukuri resources skills. that, through the support of government, industry, 1.and