Carbon Markets: the Simple Facts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

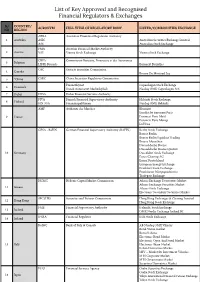

List of Key Approved and Recognised Financial Regulators & Exchanges

List of Key Approved and Recognised Financial Regulators & Exchanges S/ COUNTRY/ ACRONYM FULL TITLE OF REGULATORY BODY LISTED/COMMODITIES EXCHANGE NO REGION APRA Australian Prudential Regulation Authority 1 Australia ASIC Australian Securities Exchange Limited ASE Australian Stock Exchange FMA Austrian Financial Market Authority 2 Austria VSE Vienna Stock Exchange Vienna Stock Exchange CBFA Commission Bancaire, Financiere et des Assurances 3 Belgium LIFFE Brussels Euronext Bruxelles OSC Ontario Securities Commission 4 Canada Bourse De Montreal Inc 5 *China CSRC China Securities Regulatory Commission Finanstilsynet Copenhagen Stock Exchange 6 Denmark Dansk Autoriseret Markedsplads Nasdaq OMX Copenhagen A/S 7 Dubai DFSA Dubai Financial Services Authority FIVA Finnish Financial Supervisory Authority Helsinki Stock Exchange 8 Finland FIN-FSA Finansinspektionen Nasdaq OMX Helsinki AMF Authorite des Marches Bluenext Eurolist by Euronext Paris 9 France Euronext Paris Matif Euronext Paris Monep LCH SA GFSA - BaFIN German Financial Supervisory Authority (BAFIN) Berlin Stock Exchange Boerse Berlin Boerse Berlin Equiduct Trading Boerse Muenchen Duesseldorfer Boerse Duesseldorfer Boerse Quotrix 10 Germany Dusseldorf Stock Exchange Eurex Clearing AG Eurex Deutschland European Energy Exchange Frankfurt Stock Exchange Frankfurter Wertpapierboerse Tradegate Exchange HCMC Hellenic Capital Market Commission Athens Exchange Derivatives Market Athens Exchange Securities Market 11 Greece Athens Stock Exchange Electronic Secondary Securities Market SFC (HK) -

Annotated Presentation of Regulated Markets and National Provisions

15.7.2011 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 209/21 Annotated presentation of regulated markets and national provisions implementing relevant requirements of MiFID (Directive 2004/39/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council) (2011/C 209/13) Article 47 of the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (Directive 2004/39/EC, OJ L 145, 30.4.2004) authorises each Member State to confer the status of ‘regulated market’ on those markets constituted on its territory and which comply with its regulations. Article 4, paragraph 1, point 14 of Directive 2004/39/EC defines a ‘regulated market’ as a multilateral system operated and/or managed by a market operator, which brings together or facilitates the bringing together of multiple third-party buying and selling interests in financial instruments — in the system and in accordance with its non-discretionary rules — in a way that results in a contract, in respect of the financial instruments admitted to trading under its rules and/or systems, and which is authorised and functions regularly and in accordance with the provisions of Title III of Directive 2004/39/EC. Article 47 of Directive 2004/39/EC requires that each Member State maintains an updated list of regulated markets authorised by it. This information should be communicated to other Member States and the European Commission. Under the same article (Article 47 of Directive 2004/39/EC), the Commission is required to publish a list of regulated markets, notified to it, on a yearly basis in the Official Journal of the European Union. The present list has been compiled pursuant to this requirement. -

T H E Kyoto Mechanisms & Global C L I M a T E C H a N

T h e Kyoto Mechanisms & Global c l i m a t e c h a n g e Coordination Issues and Domestic Po l i c i e s Prepared for the Pew Center on Global Climate Change by Er ik Ha i t es M ARGAR E E C O N SU L TA N TS I N C . Mal ik Amin Asl am E NVOR K R E S E AR C H A N D D EV E L O P M E N T O RGA N I S AT I O N Sept emb er 2000 Contents Foreword ii E xecutive Summary iii I. Introduction 1 A. The Benefits of Emissions Trading 1 B. The Kyoto Mechanisms 2 C. Implementation Issues 4 D. The Kyoto Mechanisms and Domestic Policies 5 E. Equity, Environmental Integrity, and Economic Efficiency 6 II. Proposed Rules for the Kyoto Mechanisms 9 A. Participation by Legal Entities 9 B. Substitution Among Mechanisms (Fungibility) 10 C. Supplementarity 12 D. Penalties, Enforcement, and Liability 13 E. International Review of Projects 15 F. The Need To Demonstrate Additionality 17 G. Approval by Annex B Parties 19 H. Date When Projects Can Begin To Generate Allowances 20 + I. Eligibility of Sink Enhancement Projects 21 J. Levies on Transactions 21 K. Contribution to Sustainable Development 23 III. Coordination of the Kyoto Mechanisms with Domestic Policies 24 A. Potential Purchase and Use of Kyoto Mechanism Allowances by Legal Entities 25 B. Potential Sales of Kyoto Mechanism Allowances by Legal Entities 29 C. Coordination of Domestic Policies with the Rules of the Kyoto Mechanisms 31 + I V. -

EU ETS Handbook ©Istock

EU ETS Handbook ©iStock Climate Action Contents Using the guide 3 What is the EU ETS? 4 Benefits of cap-and-trade 5 History of the EU ETS 7 EU legislative structure and the EU ETS 9 How does the EU ETS contribute to meeting the EU’s climate policy goals? 12 How does the EU ETS contribute to a competitive economy? 14 How does the EU ETS work? 16 Main EU ETS features over the years 18 Design structure 20 What GHG emissions does the EU ETS cover? 20 What is the cap on GHG emissions? 22 How are allowances allocated? 24 How allocation has evolved 26 Auctioning in the EU ETS 28 Auctioning bodies and venues 29 Distribution of auctioning rights 31 Auctioning in practice 32 Use of auction revenues 35 Transitional free allocation for modernisation of the power sector (Article 10c) 36 NER300 fund for demonstration projects 38 Free allocation in the EU ETS 40 Timing of determining free allocation 41 Free allocation shifts compliance costs 42 From national allocation to EU-wide allocation; NAPs to NIMs 43 Calculating free allocation using benchmarks 44 Limit on total free allocation: Correction factors 46 What is a benchmark? 47 The process of developing the benchmarks 48 Product benchmark curves and values 49 Product benchmark for free allocation 51 Fall-back approaches for free allocation 53 Historical Activity Level 55 Cross-boundary energy - Who should receive free allocation? 56 Capacity changes/Changes in emissions 58 When is an installation a new entrant? 59 Addressing the risk of carbon leakage 60 Addressing the risk of carbon leakage: Compensation -

Titelfolie Logo Dachmarke

Carbon Markets – General Introduction Urs Brodmann First Climate IATA / IETA Workshop Singapore, 22 March 2017 Your partner for climate protection and sustainability – since 1999 First Climate is a globally leading carbon market service provider. We Our products and develop emission reduction projects, originate and trade carbon credits services at a glance and manage portfolios of carbon assets. We act as a consultant to corporate and public sector clients. CO2-Compliance Services Climate Neutral Services Carbon/Water Project Development Green Energy Services Public Climate Action Carbon Asset Management Water Management Services Pellets2go 2 Facts & Figures Facilitated over VERs retired on More than 500 200,000,000 EUR in behalf of our clients: corporate clients project finance 24.000.000 Generated Renewable energy 32.000.000 We support more than certificates sourced on CERs 200 carbon offset projects behalf of more than 150 clients 3 Outline 1. Introduction to Carbon Markets 2. Key Concepts for Baseline & Credit Mechanisms 3. Credit Types and Standards 4. Carbon Markets to Date; Supply/Demand Considerations 4 Compliance vs. Voluntary Markets • Carbon markets exist both under compliance schemes and as voluntary programs • Compliance markets are created and regulated by mandatory regional , national, and international carbon reduction regimes, such as the Kyoto Protocol an the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) • Voluntary markets function outside of the compliance markets and enable companies, governments and individuals to purchase -

Carbon Markets 101 the ULTIMATE GUIDE to GLOBAL OFFSETTING MECHANISMS

Carbon markets 101 THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO GLOBAL OFFSETTING MECHANISMS Version 2.0 July 2020 co2 co2 co2 co2 co2 1 Introduction Contents This briefing gives an overview of the current discussions under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement which establishes the foundation for market-based climate measures after 2020. It lays out key lessons from the Kyoto Protocol markets, highlights essential issues within the Article 6 negotiations, and provides recommendations on how to solve them. It concludes with an overview of non-Article 6 carbon Introduction 3 markets, which have ties to the Article 6 discussions, such as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), a carbon market specifically designed for airlines. Trading greenhouse gas emissions 3 Distinguishing between two forms of carbon markets 3 Trading greenhouse gas emissions UN carbon markets 4 Carbon markets are one of the tools to tackle the climate change problem, i.e. the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Since we only have one atmosphere, it does not matter where the emissions are released, because they will soon spread around the Lessons from the Kyoto Protocol for the Article 6 markets 4 earth, creating a greenhouse effect. Following this logic, if a group of people, countries or companies agrees to limit their emissions to a certain amount (aka adopt a “carbon budget”), it does not matter how much each person emits, or where they do so, as long as the The Clean Development Mechanism 4 whole group does not emit more than what they committed to. Since it doesn’t matter where we reduce emissions, the argument behind carbon trading is that the best way to take climate action is to reduce emissions where it is easiest (i.e. -

EU Emissions Trading the Role Of

School of Management and Law EU Emissions Trading: The Role of Banks and Other Financial Actors Insights from the EU Transaction Log and Interviews SML Working Paper No. 12 Johanna Cludius, Regina Betz ZHAW School of Management and Law St.-Georgen-Platz 2 P.O. Box 8401 Winterthur Switzerland Department of Business Law www.zhaw.ch/abl Author/Contact Johanna Cludius [email protected] Regina Betz [email protected] March 2016 ISSN 2296-5025 Copyright © 2016 Department of Business Law, ZHAW School of Management and Law All rights reserved. Nothing from this publication may be reproduced, stored in computerized systems, or published in any form or in any manner, including electronic, mechanical, reprographic, or photographic, without prior written permission from the publisher. 3 Abstract This paper is an empirical investigation of the role of the financial sector in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS). This topic is of particular interest because non-regulated entities are likely to have played an important part in increasing the efficiency of the EU ETS by reducing trading transaction costs and providing other services. Due to various reasons (new rules and regulations, reduced return prospects, VAT fraud investigations) banks have reduced their engagement in EU Emissions Trading and it is unclear how this will impact on the functioning of the carbon market. Our regression analysis based on data from the EU Transaction Log shows that large companies and companies with extensive trading experience are more likely to interact with the financial sector, which is why we expect banks’ pulling out of the EU ETS to affect larger companies more significantly. -

Effects of Carbon Pricing on EU Equity Markets

Stockholm School of Economics Master Thesis in Finance Effects of Carbon Pricing on EU Equity Markets Andrii Shekhirev* 2011.06.20 The current work examines whether the price changes of European Union Allowance (EUA) contracts for emitting carbon dioxide affect the price dynamics of the European equity markets. The author uses the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) and Vector Error Correction (VECM) models in four specifications to investigate the linkages between the EUA market and major stock indexes of 27 EU countries which are participating in the second phase of the European Emissions Trading System. The regression models, together with Granger causality testing, suggest that stock markets of several developed European countries exhibit significant negative responses to EUA price shocks. In particular, CAC 40 (France), DAX 30 (Germany), AEX (the Netherlands), and FTSE MIB (Italy) indexes have been found to react to the EUA market movements. This may serve as a hint for the growing importance of the price of carbon as an additional risk factor for businesses given that emission quotas are being consistently tightened every year. Author: Andrii Shekhirev Supervisor: Cristian Huse Discussant: Huizi Zeng Date of Presentation: June 13th, 2011 Final Thesis: June 20th, 2011 Keywords: emissions trading, carbon markets, market linkages, ETS, price shocks, vector autoregression, VAR, Granger causality *[email protected] Andrii Shekhirev Effects of Carbon Pricing on EU Equity Markets Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... -

CHAPTER 1: EU ETS: Origins, Description and Markets in Europe

CO2 Markets Maria Mansanet Bataller Motivation Climate Change Importance Increasingly Kyoto Protocol: International Response to Climate Change Flexibility Mechanisms EMISSIONS TRADING CARBON MARKETS The presentation is organized as follows… Carbon Trading Origins. Carbon Trading in Europe : the EU ETS. Carbon Markets in Europe. Linking with UN Carbon Markets. Conclusion and final remarks The presentation is organized as follows… Carbon Trading Origins. Carbon Trading in Europe : the EU ETS. Carbon Markets in Europe. Linking with UN Carbon Markets. Conclusion and final remarks Origins of the EU ETS Kyoto Protocol ( UNFCCC). 1997 & 2005 55 Parts of the Convention including the developed countries representing 55% of their total emissions. Global emissions by 5% from 1990. Commitment period 2008 - 2012. 6 GHG: CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, and SF6. ol Canada otoc r Liechtenstein oto P y New he K Zealand to t e Australia anc t s i D Japan ) Switzerland % United States 2005 ( Norway ange 1990- h Monaco c ons i s s Croatia i em al e Iceland R Russian et Federation g r a Ukraine o T ot y K 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 10 Commitments by Country 40 30 20 -1 -5 -2 -3 -4 -6 Spain Austria ol oc ot Luxembourg r Italy o P ot y Portugal he K Denmark t o Ireland e t anc Slovenia t EU-15 Dis Belgium Netherlands ) % Germany Greece 2005 ( France Finland United Kingdom hange 1990- Sweden c ons Czech Rep. i s Slovakia is Poland Hungary Real em Romania Bulgaria get r Estonia a Lithuania o T ot y Latvia K 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 60 50 40 30 20 10 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 Commitments in Europe Kyoto Flexibility Mechanisms Realization Emission Reduction Projects Joint Implementation (art. -

2015 Registration Document | 02

2015 REGISTRATION DOCUMENT | 02 CONTENTS Risks 2 5 Operating and fi nancial review 75 Strategic Risks 3 5.1 Overview 76 Financial Risks 5 5.2 Material contracts and related party Operational Risks 6 Transactions 96 5.3 Legal Proceedings 98 5.4 Insurance 100 Presentation of the Group 9 1 5.5 Liquidity and Capital Resources 101 1.1 Company Profi le 10 5.6 Tangible Fixed Assets 102 1.2 Strategy 12 1.3 Description of the Business 13 Financial Statements 103 1.4 Regulation 25 6 6.1 Consolidated Income Statement 104 6.2 Consolidated Statement Corporate Governance 29 2 of Comprehensive Income 105 2.1 Corporate Governance 30 6.3 Consolidated Balance Sheet 106 2.2 Management & Control Structure 32 6.4 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 107 2.3 Report of the Supervisory Board 43 6.5 Consolidated Statement of Changes 2.4 Remuneration report 45 in Parent’s Net Investment 2.5 Corporate Social Responsibility 50 and Shareholders’ Equity 108 6.6 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 110 3 Selected historical combined fi nancial 6.7 Euronext N.V. Company Financial Statements information and other fi nancial for the year ended 31 December 2015 151 information 57 6.8 Notes to Euronext N.V. Financial Statements 153 6.9 Other information 167 4 General description of the Company and its share capital 61 Glossary 169 4.1 Legal Information on the Company 62 G 4.2 Share Capital 62 4.3 Shareholder structure 64 4.4 Share Classes and Major Shareholders 64 4.5 General Meeting of Shareholders and Voting Rights 69 4.6 Anti-Takeover Provisions 70 4.7 Obligations of Shareholders and Members of the Managing Board to Disclose Holdings 70 4.8 Short Positions 71 4.9 Market Abuse Regime 72 4.10 Transparency Directive 72 4.11 Dutch Financial Reporting Supervision Act 73 4.12 Dividends and Other Distributions 73 4.13 Financial Calendar 74 - 2015 Registration document 2015 Registration Document including the Annual Financial Report Euronext N.V. -

The Government of the Republic of Croatia 3940

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA 3940 Pursuant to Article 48 paragraph 3 of the Air Protection Act (Official Gazette 178/2004 and 60/2008), the Government of the Republic of Croatia, at its session on 5 December 2008, adopted the following REGULATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE FLEXIBLE MECHANISMS OF THE KYOTO PROTOCOL GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1 (1) This Regulation prescribes the manner of carrying out the procedure for implementing the flexible mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol, the members of the Committee for the assessment of project activities or programmes, and the manner of reporting on their implementation. (2) This Regulation shall apply to the manner of implementing the Kyoto Protocol flexible mechanisms, i.e.: – project activities of the Clean Development Mechanism, – project activities of the Joint Implementation Mechanism on the territory and outside the territory of the Republic of Croatia, –international greenhouse gas emission trading. Article 2 The provisions of this Regulation shall not apply to: – project activities which involve use of nuclear energy, – project activities in relation to land-use, land-use change and forestry if genetically modified organisms or invasive foreign species are used. Article 3 (1) For the purpose of this Regulation, the following definitions apply: 1. Annex I Party to the UNFCCC – party specified in Annex I to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (hereinafter referred to as: the UNFCCC) that has ratified the Kyoto Protocol, 2. Clean Development Mechanism – Kyoto Protocol instrument for the implementation of project activities for reducing or eliminating emissions in countries which are not parties to Annex I to the UNFCCC, 3. -

NYSE Euronext and APX to Establish NYSE Bluetm, a Joint Venture Targeting Global Environmental Markets

NYSE Euronext and APX to Establish NYSE BlueTM, a Joint Venture Targeting Global Environmental Markets • NYSE Euronext will contribute its ownership in BlueNext in return for a majority interest in the joint venture; • APX, a leading provider of operational infrastructure and services for the environmental and energy markets, will contribute its business in return for a minority interest in the venture; • NYSE Blue will focus on environmental and sustainable energy initiatives, and will further NYSE Euronext’s efforts to increase its presence in environmental markets globally while attracting new partners and customers. New York, September 7, 2010 -- NYSE Euronext (NYX) today announced plans to create NYSE BlueTM, a joint venture that will focus exclusively on environmental and sustainable energy markets. NYSE Blue will include NYSE Euronext’s existing investment in BlueNext, the world’s leading spot market in carbon credits, and APX, Inc., a leading provider of regulatory infrastructure and services for the environmental and sustainable energy markets. NYSE Euronext will be a majority owner of NYSE Blue and will consolidate its results. Shareholders of APX, which include Goldman Sachs, MissionPoint Capital Partners, and ONSET Ventures, will take a minority stake in NYSE Blue in return for their shares in APX. Subject to customary closing conditions, including APX shareholder approval and regulatory approvals, the APX transaction is expected to close by the end of 2010. NYSE Blue will provide a broad offering of services and solutions including integrated pre-trade and post-trade platforms, environmental registry services, a front-end solution for accessing the markets and managing environmental portfolios, environmental markets reference data, and the BlueNext trading platform.