Washington Monument Grounds Historic District Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider There are so many things to do when visiting D.C., many for free, and here are a few you may have not done before. They may make it worthwhile to come to D.C. early or to stay to the end of the weekend. Getting to the Sites: • D.C. Sites and the Pentagon: Metro is a way around town. The hotel is four minutes from the Metro’s Mt. Vernon Square/7th St.-Convention Center Station. Using Metro or walking, or a combination of the two (or a taxi cab) most D.C. sites and the Pentagon are within 30 minutes or less from the hotel.1 Googlemaps can help you find the relevant Metro line to use. Circulator buses, running every 10 minutes, are an inexpensive way to travel to and around popular destinations. Routes include: the Georgetown-Union Station route (with a stop at 9th and New York Avenue, NW, a block from the hotel); and the National Mall route starting at nearby Union Station. • The Mall in particular. Many sites are on or near the Mall, a five-minute cab ride or 17-minute walk from the hotel going straight down 9th Street. See map of Mall. However, the Mall is huge: the Mall museums discussed start at 3d Street and end at 14th Street, and from 3d Street to 14th Street is an 18-minute walk; and the monuments on the Mall are located beyond 14th Street, ending at the Lincoln Memorial at 23d Street. -

Potomac Flats.Pdf

Form 10-306 STATE: (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) ———m COMMON: East and West Potomac Parks AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: area bounded by Constitution Avenue, 17th Street, Indepen dence Avenue, Washington Channel, Potomac River and Rock Creek Park CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL ^ongressman Washington Walter E. Fauntroy, D.C. STATE: CODE COUNTY: District of Columbia 11 District of Columbia 001 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC [X] District Q Building |XJ Public Public Acquisition: CD Occupied Yes: QSite CD Structure CD Private CD In Process I | Unoccupied I | Restricted CD Object CD Both I | Being Considered [ | Preservation work Qg) Unrestricted in progress LDNo PRESENT USE (Check One of More as Appropriate) I | Agricultural [XJ Government ffi Park 1X1 Transportation | | Commercial CD Industrial CD Private Residence CD Other (Specify) CD Educational CD Military [ | Religious I | Entertainment [~_[ Museum I | Scientific National Park Service, Department of the Interior REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) STREET AND NUMBER: National Capital Parks 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. CITY OR TOWN: CODE Washington COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: None exists—parks are reclaimed land TITLE OF SURVEY: National Park Service survey in compliance with Executive Order 11593 DATE OF SURVEY: [29 Federal CD State CD County CD Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: 09 National Capital Parks STREET AND NUMBER: 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. Cl TY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 11 ©-©--- - - "- © - - _--_ -.- _---..-- . _ - B& Exc9\\en* [~~| Good- v'Q FVir - "^Q Deteriorated : - fH Ruins "-': - PI Unexposed : CONDWIOK -=."'-". -

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt. Phone Fax Code ABLI RegionType Unit U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Alaska Region (FWS) HASKETT,GEOFFREY [email protected] 1011 East Tudor Road Phone: 907‐ 786‐3309 Anchorage, AK 99503 Fax: 907‐ 786‐3495 Naitonal Park Service(NPS) Alaska Region (NPS) MASICA,SUE [email protected] 240 West 5th Avenue,Suite 114 Phone:907‐644‐3510 Anchoorage,AK 99501 Bureau of Indian Affairs(BIA) Alaska Region (BIA) VIRDEN,EUGENE [email protected] Bureau of Indian Affairs Phone: 907‐586‐7177 PO Box 25520 Telefax: 907‐586‐7252 709 West 9th Street Juneau, AK 99802 Anchorage Agency Phone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Indian Affairs Telefax:907 271‐4477 3601 C Street Suite 1100 Anchorage, AK 99503‐5947 Telephone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Land Manangement (BLM) Alaska State Office (BLM) CRIBLEY,BUD [email protected] Alaska State Office Phone: 907‐271‐5960 222 W 7th Avenue #13 FAX: 907‐271‐3684 Anchorage, AK 99513 United States Geological Survey(USGS) Alaska Area (USGS) BARTELS,LESLIE lholland‐[email protected] 4210 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99508‐4626 Phone:907‐786‐7055 Fax: 907‐ 786‐7040 Bureau of Ocean Energy Management(BOEM) Alaska Region (BOEM) KENDALL,JAMES [email protected] 3801 Centerpoint Drive Phone: 907‐ 334‐5208 Suite 500 Anchorage, AK 99503 Ralph Moore [email protected] c/o Katmai NP&P (907) 246‐2116 ANIA ANTI AKR NPRES ANIAKCHAK P.O. Box 7 King Salmon, AK 99613 (907) 246‐3305 (907) 246‐2120 Jeanette Pomrenke [email protected] P.O. -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

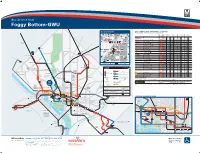

Bus Service from Foggy Bottom-GWU

Bus Service from Foggy Bottom-GWU Silver Spring BUS BOARDING MAP BUS SERVICE AND BOARDING LOCATIONS The table shows approximate minutes between buses; check schedules for full details 1/4 mile Best radius West End walking Branch Western MONDAY TO FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY distance Ritz-Carlton e Library v BOARD AT One A L St e L St Washington ir ROUTE DESTINATION BUS STOP AM RUSH MIDDAY PM RUSH EVENING DAY EVENING DAY EVENING t t h s S Eastern Ave S Avenue Pe Circle p George t t h n d m n t r t S s Suites y a S 4 Washington lv 3 a A H S METROBUS h 2 2 n d t t ia University A D n s 5 v e ew 2 1 2 Hospital N 2 The hington C 2 as ir 30N 30S 33 Friendship Heights m 10-20 10-20 7-15 15-30 10-20 15-30 10-20 15-30 Melrose J W CD George 30N 36 Naylor Rd m 15-25 20 15 15-30 20-30 20-30 30 30 29 K St Washington K St 29 BF Bethesda Statue C International 30S 32 Southern Ave m 15-25 20 10-15 15-30 20-30 20-30 20-40 20-40 Finance BF P Corporation t e B nn C s 31 Friendship Heights m 30 30 12-20 30 30 30 30 30 ylv Takoma s a DF nia w George Washington Western Ave Queen Annes Ln Av o University Hospital e n 31 32 36 Potomac Park 3-6 6-14 7-20 10-20 10-15 12-30 12-20 30 S I St E L1 Chevy Chase Circle F 33 Federal Triangle B 5-15 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 Georgia Ave I St e I St Military Rd v 38B Ballston-MU m 12-25 20 15 20-30 30 30 30 30 A Connecticut Ave Riggs Rd Foggy Bottom- CD re E 31 t GWU Inn hi S s GWU 38B Farragut N&W 12 20 9-15 20-30 30 30 30 30 33 h m Military Rd t mp 5 A a 80 2 Academic & Marvin 30N H Doubletree 16th St 14th St Fort Totten Galloway -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Washington

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2009 Washington Monument Grounds Washington Monument Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Washington Monument Grounds Washington Monument Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. In addition, -

The George Washington University

The George Washington University Degree Programmme Does your University accept the Yes. HKCEE grades are considered direct equivalents to GCSE HKCEE and HKALE for exams. The HKALE grades are equivalent to GCE A-level. admission to your University? What are the entry requirements HKALE grades A-C. for a student with HKCEE and HKCEE in a broad range of subjects – the majority should be grade HKALE qualifications entering A-B. your University? Do students with HKCEE and Students must take the SAT or ACT and have an official score report HKALE qualifications have to sit sent from the College Board to the George Washington University. an entrance examination to enter your University? Is there a language proficiency Students must submit an official TOEFL score (Test of English as a test that students with HKCEE Foreign Language) unless the student scores a 550 or higher on the and HKALE qualifications critical reading section of the SAT. wishing to enter your University must take? Is there a standard on an For TOEFL minimum requirements visit: international English scale that http://gwired.gwu.edu/adm/apply/international.html students with HKCEE and HKALE qualifications wishing to enter your University must reach? Are there any other tests that No. students with HKCEE and HKALE qualifications wishing to enter your University must take? When must they be taken? Is there an entry quota that No. applies to students with HKCEE and HKALE qualifications wishing to enter your University? Where can information be Up-to-date information can be found -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

Staff Recommendation

STAFF RECOMMENDATION NCPC File No. 7060 THE NATIONAL MALL NATIONAL MALL PLAN Washington, DC Submitted by the National Park Service November 23, 2010 Abstract The National Park Service has submitted the National Mall Plan for the management and stewardship of the land in its jurisdiction on the National Mall. The plan is a framework for future decision-making and implementation of physical improvements for the protection of the National Mall’s renowned natural and cultural resources, new visitor amenities and services, additional accommodations for First Amendment demonstrations and special events, better- linked circulation in a range of modes, accessibility throughout the Mall, additional opportunities for active and passive recreation, and improved visitor information and education. The National Park Service’s goal for the National Mall is that it be a model in sustainable urban park development, resource protection, and management. Commission Action Requested by Applicant Approval of the National Mall Plan, pursuant to 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) and (d)). Executive Director’s Recommendation The Commission: Approves the National Mall Plan, as shown on NCPC Map File No. 1.41(78.00)43205. Notes that: • The National Mall Plan is based on the Preferred Alternative presented and analyzed in the National Park Service’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, Record of Decision, and Section 106 Programmatic Agreement. NCPC File No. 7060 Page 2 • Additional compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act will be required for the development and implementation of many of the National Mall Plan’s proposed projects, and that the siting and design of individual projects are subject to the Commission’s review and approval. -

From HFC's Director

National Park Service HFCU.S. Department of the Interior onMEDIA May / June | 2008 Issue 23 Yellowstone National Park’s In This Issue “Roving Ranger” videocasts enable visitors to download interpretive content from Interpretive the Web to their own digital Techniques in device, and then play back 2 New Media the content during their park visit. New technology like this gives our audiences greater control over when, What New where, and how they receive Media Products interpretive information. 5 are Parks Using Learn more about new me- Today? dia products like this starting on page 5. (NPS Photo) New Employees and Staff News 6 at Harpers Ferry From HFC’s Director Center New media—digital and often web-based—off er the interpretation and education pro- HFC Products fessional many opportunities to deliver information to our many audiences. More than 11 Receive Awards ever before, these tools allow us to target our messages to very specifi c demographics and create a whole new palette of experiences for visitors. New Film Pre- Each of the “new media” technologies has its own content requirements, operational mieres at Home- regimes, and investment and life cycle costs. As a result, some are more successful in park 14 stead National environments than others. In this issue, we take a look at a few of the new technologies Monument that have been used in our parks and hear from experienced park professionals about the challenges, successes, and lessons learned as they have implemented new media products in their park. New Graphic 15 Identity Website Even though many of these exciting new media solutions are by design “user generated” Launched at the park site, Harpers Ferry Center looks forward to helping parks prepare their con- tent and create standards that benefi t the NPS system-wide. -

Exclusive Rulebookrulebook

SARATOGA 1 The Turning Point of the American Revolution, 1777 EXCLUSIVEEXCLUSIVE RULEBOOKRULEBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Prepare for Play .................................................... 2 7. Special Scenario Rules ......................................... 6 2. How to Win ........................................................... 2 8. Historical Scenario, “Freeman’s Farm” ................ 7 3. Special Rules ........................................................ 3 9. Scenario Victory Conditions ................................. 7 4. Variants ................................................................ 4 10. Special Scenario Rules ......................................... 8 5. Saratoga “Next Day” Scenario Setup ................... 4 Historical Article: Saratoga .......................................... 9 6. Scenario Victory Conditions ................................. 5 Counter scans ............................................................... 15 GMT Games, LLC Ammo Depletion Log .................................................. 16 P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com © 2006 and 2017 GMT Games, LLC 3rd Edition 2 SARATOGA 1.4 Scenario Length Introduction The scenario begins on Turn 1, and ends on Turn 12, unless ei- This, the Third Edition of Saratoga, contains significant differ- ther side achieves a Decisive or Substantial victory before then. ences from previous editions including rules changes or modifi- cations, changes in terrain, and new or re-named units. Terrain 1.5. Player Order and Initiative and -

K. Savage, “The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight

The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight to Erect a National Memorial Author(s): Kirk Savage Reviewed work(s): Source: Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Winter, 1987), pp. 225-242 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181181 . Accessed: 26/01/2012 09:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Winterthur Portfolio. http://www.jstor.org The Self-made Monument George Washington and the Fight to Erect a National Memorial Kirk Savage HE 555-FOOT OBELISK on the Mall in Even in his own time Washington and the nation Washington, D.C., is one of the most con- he led were largely products of the collective im- spicuous structures in the world, standing agination. America was then-and to some extent alone on a grassy plain at the very core of national remains-an intangible thing, an idea: a voluntary power-approximately the intersection of the two compact of individuals rather than a family, tribe, great axes defined by the White House and the or race.