Rock Climbing Survey Results, Obed Wild And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines Compiled for the Victorian Climbing Community Revision: V04 Published: 15 Sept 2020 1 Contributing Authors: Matthew Brooks - content manager and writer Ashlee Hendy Leigh Hopkinson Kevin Lindorff Aaron Lowndes Phil Neville Matthew Tait Glenn Tempest Mike Tomkins Steven Wilson Endorsed by: Crag Stewards Victoria VICTORIAN CLIMBING MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES V04 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 2 Foreword - Consultation Process for The Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines The need for a process for the Victorian climbing community to discuss widely about best rock-climbing practices and how these can maximise safety and minimise impacts of crag environments has long been recognised. Discussions on these themes have been on-going in the local Victorian and wider Australian climbing communities for many decades. These discussions highlighted a need to broaden the ways for climbers to build collaborative relationships with Traditional Owners and land managers. Over the years, a number of endeavours to build and strengthen such relationships have been undertaken; Victorian climbers have been involved, for example, in a variety of collaborative environmental stewardship projects with Land Managers and Traditional Owners over the last two decades in particular, albeit in an ad hoc manner, as need for such projects have become apparent. The recent widespread climbing bans in the Grampians / Gariwerd have re-energised such discussions and provided a catalyst for reflection on the impacts of climbing, whether inadvertent or intentional, negative or positive. This has focussed considerations of how negative impacts on the environment or cultural heritage can be avoided or minimised and on those climbing practices that are most appropriate, respectful and environmentally sustainable. -

Rescue of an Injured Climber from the Redguard Route in Eldorado Canyon State Park

Rescue of an injured climber from the Redguard Route in Eldorado Canyon State Park On the morning of the June 26th 2010, Boulder County dispatch notified Rocky Mountain Rescue Group (RMRG) of an injured climber in need of assistance on Redgarden Wall in Eldorado Canyon State Park. The ensuing rescue took three hours, involved 32 mountain rescue personnel, medical personnel from three agencies, Boulder County Sherriff Officers, and Colorado State Park personnel. Events Leading to the Accident [Based on a detailed summary of the accident written by Bill Wright, one of the climbers. RMRG sincerely appreciates Bill Wright's public support. However, other than receiving rescue services, he is not affiliated with RMRG. His words and opinions are his own. Two experienced climbers were attempting to complete 100 pitches of climbing within a single day in Eldorado Canyon State Park. After already climbing 29 pitches, the team started the Redguard route, traditionally a 7-pitch climb rated 5.8 on the Redgarden Wall. To achieve the 100-pitch goal the team was simul-climbing, a method where neither the leader nor follower has an active belay; rather they climb at approximately the same speed with a near taught rope and several pieces of rock protection between them. When the lead climber was about 300 feet above the ground, he fell an estimated 120 - 140 feet and came to a stop apparently inverted and unconscious, 15 - 30 feet above a large ledge. The follower was able to raise the attention of a runner passing on the trails below who then called 911. -

Anchors BODY04

Part 2 of 3 Why Fixed Anchors Are Needed ecreational rock climbing, ranging from traditional mountain- Sport climbing evolved through technological advances in eering to sport climbing, is increasing on national forests. climbing equipment. This type of climbing is usually done on a RR Recreational rock climbing has occurred on national forests single pitch, or face, and often relies on bolts. Sport climbing for many years, inside and outside of designated wilderness. differs from traditional rock climbing where more strategic, and Rock climbers routinely use fixed anchors to assist them in sometimes horizontal, movement is favored over a quick vertical their climb and to help them navigate dangerous terrain safely. climb and descent. Bolted routes increase the margin of safety The safest, most common reliable fixed anchor is an expansion for climbers. bolt, a small steel bolt placed in a hole that has been drilled into the rock (figure 1). Frequently, a “hanger” is attached to an Traditional rock climbing uses removable protection such as expansion bolt to accommodate a carabiner or sling (figure 2). nuts, stoppers, or cam devices, placed into a crack of the rock formation (figure 3). Traditional rock-climbing protection devices require sound judgment for placements. These protection devices are rated for strength in pounds or metric units of force called kilonewtons. A kilonewton rating measures the amount of force that would break a piece of equipment during a fall. Even traditional climbing requires bolts to be placed at the top of a vertical crag for rappelling if there is no other way of descending. Figure 1—An expansion bolt is placed in a drilled hole into the rock. -

The Development of Equipment to Reduce Risk in Rock Climbing

The development of equipment to reduce risk in rock climbing R. A. Smith Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Shef®eld, UK. Abstract The historical development of protection systems for rock climbing is summarized. Rapid advances in the design and availability of equipment since 1945 has enabled climbers to fall with much reduced risk of death or serious injury. Mention is made of the wider application of climbing protection equipment to industrial situations and some ideas for the discussion of climbing equipment in teaching examples are introduced. Keywords: Rock climbing, mountaineering, rope, protection equipment, impact loads, falls. Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are nought without prudence, and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste; look well to each step; and from the beginning think what may be the end (Whymper, 1871). Review of the development of rock climbing To the uninitiated, the joining of a team of protection systems climbers together on a rope represents a source of danger since, should one slip, the remainder are pulled off. Indeed some of the earliest mountain- Beginnings eering accidents in the European Alps seemed to Rock climbing, a branch of the wider sport of substantiate this idea, and the term rope was used as mountaineering, involves an element of risk. This is a noun to describe the system of the climbers and one of its attractions. In the approximately their connecting rope. One well-documented clas- 120 years since the inception of rock climbing as sic accident occurred on 14 July 1865. -

Yellow Spur Rope Failure Investigation by Rocky Mountain Rescue Group

Yellow Spur Rope Failure Investigation by Rocky Mountain Rescue Group March 6, 2011 On the morning of June 22, 2010, Joseph Miller fell while leading the second pitch of the Yellow Spur1 route on the Redgarden Wall in Eldorado Canyon State Park2. During the fall the climber’s rope failed, resulting in a fatal ground fall. Due to the unusual occurrence of a climbing rope failure, the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group3 (RMRG) conducted an accident investigation focused on the cause of the failure. This report contains the activities, findings and conclusions of that investigation. The intent of this report is to objectively determine what most likely happened during the accident. RMRG has no special relationship with any of the individuals or equipment manufacturers mentioned herein nor did RMRG receive any compensation for conducting this investigation. We encourage others to replicate our testing of this or similar scenarios. Figure 1a shows a photo of the Yellow Spur route with the area of the accident outlined in yellow. The second pitch of the route starts from a tree and traverses to climber’s left before heading up a dihedral (Figure 1b). The route was closed temporarily following the accident in order to gather on-site information in support of the initial investigation conducted by the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office (BCSO). Prior to re-opening the route, a detailed inspection of the second pitch of the route was performed by RMRG, and photographs were taken of the climbing protection placed by Miller during the climb. Interviews Interviews with a number of nearby climbers who witnessed the events leading to the fall and/or the fall itself were conducted by RMRG. -

Wilderness Rock Climbing Indicators

WILDERNESS ROCK CLIMBING INDICATORS AND CLIMBING MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS IN THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE by Katherine Y. McHugh A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Geography, Applied Geospatial Sciences Northern Arizona University December 2019 Approved: Franklin Vernon, Ph.D., chair Mark Maciha, Ed.D. Erik Murdock, Ph.D. H. Randy Gimblett, Ph.D. ABSTRACT WILDERNESS ROCK CLIMBING INDICATORS AND CLIMBING MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS IN THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE KATHERINE Y. MCHUGH This pilot study addresses the need to characterize monitoring indicators for wilderness climbing in the National Park Service (NPS) as which are important to monitoring efforts as components in climbing management programs per Director’s Order #41, Section 7.2 Climbing. This research adopts a utilitarian conceptual framework suited to applied management objectives. Critically, it advances analytical connections between science and management through an integrative review of the resources informing park planning; including law and policy, climbing management documents, academic research on climbing management, recreation ecology, and interagency wilderness character monitoring strategies. Monitoring indicators include biophysical, social, and administrative topics related to climbing and are conceptually structured based on the interagency wilderness character monitoring model. The wilderness climbing indicators require both field and administrative monitoring; field monitoring of the indicators should be implemented by climbing staff and skilled volunteers as part of a patrol program, and administrative indicators mirror administrative wilderness character monitoring methods that can be carried out by a park’s wilderness coordinator or committee. Indicators, monitoring design, and recommended measures were pilot tested in two locations: Grand Canyon and Joshua Tree National Parks. -

2016 Tacoma Mountaineers Intermediate Climbing Manual

TACOMA MOUNTAINEERS Intermediate Climbing Manual 2016 Table of Contents Welcome to the Tacoma Mountaineers _______________________________________________________________________ 3 Course Information _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 Course Description _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 2016 Intermediate Course Roster _______________________________________________________________________________ 7 Course Policies and Requirements _____________________________________________________________________________ 11 General Notes __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Late for Lecture / Absenteeism Policy _______________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Conservation Requirement ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Winter Overnight Requirement ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Basic Climbing Field Trip Teaching Requirement __________________________________________________________________________ 12 Mentor Program ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 13 Rope Leader, Climb Leader, & Graduation Policies __________________________________________________________ 15 Rope Lead Process ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Climbing Equipment Research2.Pdf

SCIENCE VERSUS THE MOUNTAIN AN ANTHOLOGY OF CLIMBING EQUIPMENT by James Allison WRTG 2010, Section 45 Tamara Evans November 10, 2000 On a warm, June afternoon my partner and I crested the top of Crescent Crack, a gorgeous granite rock climb in Little Cottonwood Canyon. We gazed above us at the next formation. The Coffin loomed above, aptly named not because of a grim history, but because of the six-sided rock roof above that assumed the shape of its namesake. An inviting hand and finger crack spanned vertically the mottled granite face that stretched out below the coffin-shaped roof. Neither my partner nor I wanted to stop for the day, and we soon concurred to continue climbing, rather than to take the available descent route. The weather was great, and having climbed the Coffin before, I knew it was a superb route. Soon we were on our way up. I rhythmically secured my hands and feet in the solid, beautiful crack, absorbed in the movement and nuances of the climb. I had climbed numerous times before with my partner, who was down below belaying me (passing a rope through a device ready to hold a fall). I had complete trust in her attentiveness and ability to hold my weight should I fall. The climb was sustained and enjoyably challenging. Soon I reached the base of the roof, and while hunching over, I underclinged the crack between the roof and the wall. I lackadaisically fumbled with my equipment, aiming to secure a new point of protection at the roof. -

Rope System Analysis

Rope System Analysis By Stephen W. Attaway Abstract This paper presents an analysis of the loads in a typical climbing rope system subjected to a dynamic loading from a fall. Several examples are illustrated to show how to calculate the force on ropes and anchors subjected to dynamic loads that are experienced by a falling rock climber. The force in a rope that is generated when a falling weight is arrested depends on how fast the weight is stopped. We will use the energy method to solve for the maximum strain energy in the rope. The effects of friction, dynamic rope modulus, and rope condition will also be considered. We developed some rules of thumb to help a lead climber place fall protection and understand the limitations. The amount of ‘safe’ lead out depended on the amount of rope that is between the belayer and the climber, the type and condition of the belay rope, and the type of anchor used. Motivation friction, rope condition, and belay device will be considered. Finally, we will consider how much “lead out” is safe for a Rock Climbing is a technical sport. A good understand- given rope and anchor system. Several areas for research on ing of the mechanics of anchor placement, rope behavior, dynamic rope behavior are suggested. and impact dynamics is important to climber safety. On June 23, 1996, three climbers fell to their death on the Methods of rock climbing fall protection Warpy Moople route on the formation called Muralla Grande located in the Sandia Mountains east of Albuquerque, NM. -

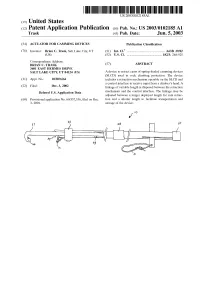

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0102185 A1 Trask (43) Pub

US 2003.0102185A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0102185 A1 Trask (43) Pub. Date: Jun. 5, 2003 (54) ACTUATOR FOR CAMMING DEVICES Publication Classification (76) Inventor: Brian C. Trask, Salt Lake City, UT (51) Int. Cl." ..................................................... A63B 29/02 (US) (52) U.S. Cl. ................................................. 182/3; 248/925 Correspondence Address: BRIAN C. TRASK (57) ABSTRACT 36O1 EAST HERMES DRIVE SALT LAKE CITY, UT 84124 (US) A device to retract cams of Spring-loaded camming devices (SLCD) used in rock climbing protection. The device (21) Appl. No.: 10/309,666 includes a retraction mechanism operable on the SLCD and a control interface to receive input from a climbers hand. A (22) Filed: Dec. 3, 2002 linkage of variable length is disposed between the retraction Related U.S. Application Data mechanism and the control interface. The linkage may be adjusted between a longer deployed length for cam retrac (60) Provisional application No. 60/337,536, filed on Dec. tion and a shorter length to facilitate transportation and 3, 2001. Storage of the device. Patent Application Publication Jun. 5, 2003. Sheet 1 of 3 US 2003/0102185 A1 N N V N ls Wr Y O As ax As Ya I re \g 14.N 3n. was M was N Y Patent Application Publication Jun. 5, 2003. Sheet 2 of 3 US 2003/0102185 A1 Patent Application Publication Jun. 5, 2003. Sheet 3 of 3 US 2003/0102185 A1 US 2003/0102185 A1 Jun. 5, 2003 ACTUATOR FOR CAMMING DEVICES 0008. A need exists for a tool to assist in retrieving cams which walk too deep into a crack for either a free-climber or RELATED APPLICATIONS an aid-climber to remove either by hand or with the assis tance of a commercially available device. -

Fixed Hardware Guidelines

THE ACTION COMMITTEE FOR ELDORADO'S FIXED HARDWARE GUIDELINES 2 February 2015 PURPOSE Climbing in Eldorado Canyon State Park Park has increased dramatically over the past thirty years. As a result of this growth, Eldorado climbers have increasingly been called upon to make decisions concerning the installation and replacement of fixed hardware as members of a larger community that extends to future users of the Park as well as those currently climbing here. The very nature of establishing a new route in Eldorado has changed dramatically. Because of their impact on the climbing community as a whole, new climbing routes requiring fixed hardware in Eldorado are now considered first and foremost a community service, and are only secondarily a means of personal expression for the individual establishing the climb. Thus, the Action Committee for Eldorado (ACE) encourages applications for new anchors and for new routes which are capable of being led safely by an Eldorado leader competent at the grade. The community's desire for growth in the Park must be balanced with a respect for the existing routes that have shaped the climbing that exists there today. Toward this end, ACE exists as a public forum to assist and regulate the installation of fixed hardware in Eldorado with the goal of facilitating controlled growth of quality routes and anchors in the Canyon. INTRODUCTION In the late 1980s, the placement of bolts became a topic of controversy in the Boulder area. During that time, Boulder Mountain Parks and City and County Open Space (BMP) prohibited the placement of new bolts: an extreme reaction, despite Boulder City Council's direction to BMP staff to create a process allowing the creation of new routes. -

Adventure Education (AP) 1

Adventure Education (AP) 1 AP 2500 Natural History and Ecology for Adventure Educators (3) ADVENTURE EDUCATION (AP) Explores the natural history and ecology of natural communities in the Northeastern US, with an emphasis on the North Woods. Provides a AP 2010 Foundations of Adventure Education (3) foundation of ecological literacy for the Adventure Educator by studying Provides a first hand experience on the use of adventure programming specific ecosystems in the region. Skills developed include creation of for personal growth and the building of a healthy community. Challenges a nature journal, identification and classification of flora and fauna, and students to explore their personal connection with the natural world via a the promotion of nature-connectedness. Additional course fee required. wilderness solo experience. Helps students explore the field of Adventure Springs. Education as a potential profession for themselves. Topics include: Prerequisite(s): AP 2010. rationale and benefits of Adventure Education's application in recreation, AP 3101 Immersion Wilderness Expedition (4) education, developmental and therapeutic settings; professional Part of the Fall Immersion Semester. Presents an in-depth coverage preparation requirements; public land resources; environmental issues; of the planning, logistical preparation, risk management, technical trends in Adventure Education. Additional course fee required. Falls and and environmental skills of extended wilderness travel. Students plan, Springs. organize, and participate in a series of wilderness trips lasting from Prerequisite(s): Adventure Education majors and minors only. 4 to 15 days. Topics include: Leave No Trace ethics; backpacking; AP 2210 Adventure Education Teaching Theories and Methods (3) canoe camping; nutrition; meal planning; outdoor cooking; stove use; Covers learning theories and teaching methods pertinent to Adventure campsite selection; modern and traditional technology used in wilderness Education.