An Exploration of Teaching Music to Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Key to Staying Committed

THE KEY TO STAYING COMMIttED Special thanks to the Simply Music team, Stephanie Iadanza, Jose Rivera and Cheri Schulzke for their brilliant work on project management, design and editing. © 2018 Neil Moore, for The Piano Coach, LLC. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means whatsoever, without written permission from Neil Moore, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews. ISBN: 978-0-9800326-2-8 If you would like more information about the Simply Music Piano program or other Simply Music programs & services please visit: simplymusic.com or call +1 800 746 7597 Contents I - Foreword 7 II - Introduction 11 1 - Sticking with Music Lessons 15 2 - Challenging Our Assumptions 19 3 - Our Objective: Establishing a Foundation 25 4 - Distinguishing the Method from the Relationship 31 5 - The Six Components of All Long-Term Relationships 35 6 - Recognizing the Long-Term Relationship 41 7 - What Seems Wrong is Actually Right! 45 8 - The Opportunity 53 9 - Why Music? 59 10 - About Parents Being Involved 63 11 - Method Coach & Life Coach 67 12 - Being Aligned 71 13 - Your Long-Term Relationship 75 14 - The Choice 77 I have been closely connected with Simply Music since its inception in 1998, and have known Neil Moore as a friend for much longer. In this long association with teachers, students and others impacted by Neil’s work, I have listened to countless stories of the ways its influence stretches far beyond the realm of music. Over and over, people find that the things they learn from Simply Music affect their broader lives in numerous ways, some surprising and profound. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Piedmont Performing Arts School

Fall Dates: Crocker Elementary Quantity Student Piano Workshop Workshops begin Piano Workshop A 3:05-4:00pm 230.00 Monday Sept. 14th Piano Workshop B 4:05-5:00pm 230.00 Student home materials Includes DVD, notes, and . Holidays/Recital practice chart ($45 Value) 1 included Piedmont Performing th Off Oct 12 (Columbus Day) Arts School Off Oct 26th (Labor Day) Please note: There will now be a Crocker Highlands Drama Program late fee of $25 for all late payments starting after the first Ages 8-10 (3-5 grades) th class. Recitals Nov. 16 If payment is not received by Class A -Class from 3:05pm-3:30pm the 2nd week your child will be Fall 2009 BRAND NEW Recital- 3:30pm - 4:00pm dropped from piano. Class B - Class from 4:05pm-4:30pm Total enclosed: __________ PIANO WORKSHOPS Recital- 4:30pm - 5:00pm Send to: PPAS MONDAYS 3311 Kempton Ave. Oakland, CA 94611 Sept. 14th-Nov 16th What Others Say About Simply Music: "This is a wonderful music program and the results are A: 3:05pm-4:00pm astounding! Even if you don’t consider yourself musically and talented, this program is designed for you! It is easy to B: 4:05pm-5:00pm understand and easy to play a full repertoire of beautiful songs from a variety of genres. I also think this program could be a major breakthrough for children with a variety of cognitive delays and learning disabilities. I love the Simply Music approach.” Dr. Anne Margaret Wright (Psy.D.) Name/Age Educational Consultant-The Old Schoolhouse Magazine Parents Names Telephone (d) Telephone (e) Email: Kristin Fairfield "Simply Music has broken the mould and set a new standard for what can be accomplished in a very short Mailing Address period of time.” Licensed Simply Music Teacher Tel: (510) 484-6932 Michelle Masoner [email protected] My child will go where after piano Piedmontperformingartsschool.org Board Member Sacramento Board of Education About Simply Music… About The Teacher Simply Music is a remarkable, Australian- developed piano and keyboard program that Kristin Fairfield (Director PPAS) learned offers a breakthrough in music education. -

Lessons for Students of All Ages!

9121 Wicker Avenue, Suite 1, St. John, IN 46373 Lessons and Music Education Discover How to Express Your Musicality! www.revolutionmusicschool.com Lessons for Students of All Ages! Student Handbook 2021-2022 Revolution Music School – Student Handbook 01AUG2021 Page 1 219-558-0519 www.revolutionmusicschool.com 2021-2022 Annual Update We have revised some policies to help handle the growing studio. These policy changes are mentioned below and explained within. Attendance and Make-ups As a rule, we do not refund for missed or canceled lessons. The group has lessons regardless of one student’s attendance. We do my best to accommodate missed lessons. Sometimes this does not always work out depending on what other classes are studying. We have placed a cap on the number of rescheduled lessons allowed per student to 2 for the year. Requirements for make-ups are also described, including giving a 7-day notice of lesson to be missed and completion of the make-up within 2 weeks. Finally, there will no longer be make-ups for missed or canceled make-up lessons. Tuition Tuition is a set monthly fee due by the 1st of each month. We pay your monthly education fees to Simply Music, per student, regardless of holidays or missed lessons due payable on the 1st. The cost of the monthly prorated tuition will remain at $90.00 for group lessons and $135.00 for private lessons. Last year we decided instead to add an extra week of vacation which will not be refunded or reimbursed. My vacation weeks will remain at four weeks for the 2021-2022 year. -

Simply Music Rhapsody Kids Make Music: Lessons 21-30

Simply Music Rhapsody Kids Make Music: Lessons 21-30 www.simplymusicrhapsody.com Contents Lesson 21: Lesson Plans . Page 3 Lesson at a Glance . Page 6 Lyrics . Page 7 Lesson 22: Lesson Plans . Page 9 Lesson at a Glance . Page 12 Lyrics . Page 13 Lesson 23: Lesson Plans . Page 15 Lesson at a Glance . Page 17 Lyrics . Page 18 Lesson 24: Lesson Plans . Page 20 Lesson at a Glance . Page 22 Lyrics . Page 23 Lesson 25: Lesson Plans . Page 25 Lesson at a Glance . Page 27 Lyrics . Page 28 Lesson 26: Lesson Plans . Page 30 Lesson at a Glance . Page 32 Lyrics . Page 33 Lesson 27: Lesson Plans . Page 35 Lesson at a Glance . Page 37 Lyrics . Page 38 Lesson 28: Lesson Plans . Page 40 Lesson at a Glance . Page 42 Lyrics . Page 43 Lesson 29: Lesson Plans . Page 45 Lesson at a Glance . Page 47 Lyrics . Page 48 Lesson 30: Lesson Plans . Page 50 Lesson at a Glance . Page 53 Lyrics . Page 54 Lessons 21-30: Song Notation . Page 56 (011713) Simply Music Rhapsody: Kids Make Music: Lessons 21-30 | © Licensed to Simply Music. All rights reserved. Page 2 of 85 21 Kids Make Music Lesson Plan 21 - Complete lesson available. What’s Activity Title Comments Needed Gathering Kangaroos Kangaroos: Gathering Drum Drum from Carnival Find different ways to play the drum in response to the music. Track of the Animals Suggest that the music indicates kangaroos jumping and pausing by Camille to look. Saint-Saëns Tideo: Tideo Encourage the children to sing “tideo.” Keep the beat on the drum Guitar/Ukulele (Ukulele) while singing hello to each child. -

Program Notes

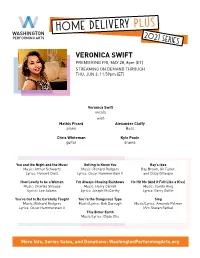

Home delivery plus 2021 SeRIeS VERONICA SWIFT PREMIERING FRI, MAY 28, 8pm (ET) STREAMING ON DEMAND THROUGH THU, JUN 3, 11:59pm (ET) Veronica Swift vocals with Mathis Picard Alexander Claffy piano Bass Chris Whiteman Kyle Poole guitar drums You and the Night and the Music Getting to Know You Ray’s Idea Music: Arthur Schwartz Music: Richard Rodgers Ray Brown, Gil Fuller, Lyrics: Howard Dietz Lyrics: Oscar Hammerstein II and Dizzy Gillespie How Lovely to be a Woman I’m Always Chasing Rainbows He Hit Me (And it Felt Like a Kiss) Music: Charles Strouse Music: Harry Carroll Music: Carole King Lyrics: Lee Adams Lyrics: Joseph McCarthy Lyrics: Gerry Goffin You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught You’re the Dangerous Type Sing Music: Richard Rodgers Music/Lyrics: Bob Dorough Music/Lyrics: Amanda Palmer Lyrics: Oscar Hammerstein II (Arr. Steven Feifke) This Bitter Earth Music/Lyrics: Clyde Otis More Info, Series Sales, and Donations: WashingtonPerformingArts.org 1 from the artist This show for Washington Performing Arts is not see a light that points towards a fuller sense of only a comeback after a year-long hiatus of no self. As a result, the songs I’ve picked for this gigs, but it is a rebirth. Originally, I was planning show encompass some of This Bitter Earth’s on performing my new album, This Bitter Earth message, but we have also included new songs in its entirety, however, I find that after a whole that mix classical with rock and roll, funk, and two years of playing these songs and recording jazz. -

Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter Shelley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Judy Tsou Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music Theory ©Copyright 2013 Peter Shelley University of Washington Abstract Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter James Shelley Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Jonathan Bernard Music Theory By now most scholars are fairly sure of what minimalism is. Even if they may be reluctant to offer a precise theory, and even if they may distrust canon formation, members of the informed public have a clear idea of who the central canonical minimalist composers were or are. Sitting front and center are always four white male Americans: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. This dissertation negotiates with this received wisdom, challenging the stylistic coherence among these composers implied by the term minimalism and scrutinizing the presumed neutrality of their music. This dissertation is based in the acceptance of the aesthetic similarities between minimalist sculpture and music. Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood,” which occupies a central role in the history of minimalist sculptural criticism, serves as the point of departure for three excursions into minimalist music. The first excursion deals with the question of time in minimalism, arguing that, contrary to received wisdom, minimalist music is not always well understood as static or, in Jonathan Kramer’s terminology, vertical. The second excursion addresses anthropomorphism in minimalist music, borrowing from Fried’s concept of (bodily) presence. -

Copyright Infringement of Music: Determining Whether What Sounds Alike Is Alike

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 15 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Winter 2013 Article 1 2013 Copyright Infringement of Music: Determining Whether What Sounds Alike Is Alike Margit Livingston Joseph Urbinato Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Margit Livingston and Joseph Urbinato, Copyright Infringement of Music: Determining Whether What Sounds Alike Is Alike, 15 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 227 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol15/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT JOURNAL OF ENTERTAINMENT AND TECHNOLOGY LAW VOLUME 15 WINTER 2013 NUMBER 2 Copyright Infringement of Music: Determining Whether What Sounds Alike Is Alike Margit Livingston* and Joseph Urbinato** ABSTRACT The standard for copyright infringement is the same across different forms of expression. But musical expression poses special challenges for courts deciding infringement disputes because of its unique attributes. Tonality in Western music offers finite compositional choices that will be pleasing or satisfying to the ear. The vast storehouse of existing public domain music means that many of those choices have been exhausted. Although independent creation negates plagiarism, the inevitable similarity among musical pieces within the same genre leaves courts in a quandary as to whether defendant composers infringed earlier copyrighted works or simply found their own way to a similar melody, harmony, rhythm, or formal structure. -

July 2015 Edition of the AAA Newsletter

NewsletterAMERICAN ACCORDIONISTS’ ASSOCIATION A bi-monthly publication of the American Accordionists’ Association Julu-August 2015 From the Editor Welcome to the July 2015 edition of the AAA Newsletter. As the final preparations are being made for our annual AAA Festival, we remind you to make plans to attend this exciting event to be held in Alexan- dria, VA, featuring renowned American and International guests, a competition held in honor of the late Faithe Deffner with an unprecedented cash prize of- fering, workshops, concerts, a Festival Orchestra and numerous social events. We invite and encourage you to submit your news items for publication in the future issues of this Newsletter. Our membership is involved in a variety of activities, and we know our readers would love to hear about these things. At any one moment, our members are performing on Broadway, at the White House, in concert both here and abroad, producing fesitvals, undertaking various International projects, working on commissions and many other accordion happenings. We thank you in advance for keeping our readers informed. As always, my thanks to immediate Past President Linda Reed and Rita Davidson for their kind assistance with the AAA Newsletter both in the final production and with providing important news items for publication. Items for the September Newsletter can be sent to me at [email protected] or to the of- ficial AAA e-mail address at: [email protected] Please include ‘AAA Newsletter’ in the subject box, so that we don’t miss any items that come in. Text should be sent within the e- mail or as a Word file attachment. -

1 U2 and Igor Stravinsky: Textures, Timbres, and the Devil Dr. Dan

U2 and Igor Stravinsky: Textures, Timbres, and the Devil Dr. Dan Pinkston Introduction At first glance, Igor Stravinsky and U2 have little in common. A Russian composer known for ballets and symphonies and four Irish rock stars inhabit different musical genres and approaches. This paper argues that although Stravinsky and U2 are from separate musical worlds, each occupies a similar place of importance within that world, and has a parallel record of artistic achievement and influence. In addition, similarities in their musical thinking and their spiritual response to fame and success will be discussed. The parallels in their musical and spiritual development are fascinating, and as this paper will show, give the listener a new perspective on hearing the music of both U2 and Stravinsky. I. The Music: Textures, Timbres, and the Minimalist Connection Texture and Timbre in the Early Works Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) initially made his mark on the musical world with a series of ballets in the early 20th century. These works, written for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russe, caused a stir in the Parisian musical scene, and Igor Stravinsky became an overnight musical phenomenon.1 The first of these ballets, The Firebird (1910), showed Stravinsky’s complete assimilation of the styles and techniques of contemporary composers such as Claude Debussy, and predecessors such as Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The work was completely modern, if not radical, and revealed that the young Stravinsky was part of an artistic movement that was breaking with the Germanic traditions of the 19th century. One of the prominent features of this new French Impressionistic and Russian Nationalistic music was the prominence of instrumental color, or timbre, in the identity of the music. -

Summer Is Taking Shape in Curtis Park by Sue Staats Viewpoint Staff Writer Music in the Park July 28

A Publication of the Sierra Curtis Neighborhood Association Vol. 35, No. 1 2791 - 24th Street, Sacramento, CA 95818 • 452-3005 • www.sierra2.org July 2013 Senior housing SUMMER is taking shape in Curtis Park By Sue Staats Viewpoint staff writer Music in the Park July 28 ffordable senior housing in Versatile Curtis Park Village moved a step musicians with a Acloser to reality June 11 when the City bold, American Council approved the plan for the The drawing depicts the housing complex Domus repertoire will 91-unit complex. It will be built and Development plans for Curtis Park Village. fire up their managed by Domus Development. instruments for a To be called Curtis Park Court, it “a great place for seniors to continue to thrive couple of hours the complex will launch new housing within the and maintain independence.” Seniors will enjoy Sunday evening 72-acre Curtis Park Village, according to Domus large indoor and outdoor community areas, July 28 for the West of Next performs July 28. president Meea Kang. Most of the 91 apartments raised-bed community gardens, and a secure bike second Music in will have one bedroom, a few will be studios or room to encourage use of the many planned bike the Park concert this summer. The band West of Next have two bedrooms. The housing is designed to paths. The building entrance will feed directly will be on stage with their new member, Lillian be affordable to seniors on a fixed income. Rents into the pedestrian bridge that will connect to McLeod. She’s an experienced actress and singer will start at $400 a month for studios and top out at the Sacramento City College light rail station. -

World of Music / Cultural Diversity in Music Education

World of Music / Cultural Diversity in Music Education ISME CMA seminar: Community Music in the Modern Metropolis Most music education in the world has been organised around the great tradition of Western classical music. This has led to an infrastructure that extends not only from Vienna to Los Angeles, but also from Cape Coast to Kuala Lumpur. Unfortunately, this solid structure has its limitations in terms of flexibility. As a consequence, many large institutions for music education at all levels have difficulty in responding to new social and artistic realities, especially in the multi-ethnic, multi-musical cities at the beginning of the third millennium. By its very nature and practice, community music can play a major role in leading the way to new approaches to music education across the board. This was the central thought behind the Community Music Activities (CMA) seminar in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 5-10 August 2002. The target gorup consisted of international professionals from various areas of music education. All participants were actively involved in the seminar, where everyone brought in their own experiences in formal and informal ways. The seminar had the following subthemes: ● Key issues and definitions of community music, defining the parameters ● Community music in practice and institutions for music education ● Community music, cultural diversity and identity ● Community music and policies of funding ● Community music and new teaching methods The seminar was organised by Rotterdam Conservatoire. As an institution for higher music education, the Conservatoire has experience with all sorts of music: classical, jazz, pop, and world music. Since twelve years there is a separate department for world music with programmes for tango, flamenco, latin, Turkish and Indian music.