Research: Report Neighbourhood Watch Building New Communities: Learning Lessons from the Thames Gateway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Papers Published

INDEX OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PAPERS PUBLISHED IN 1907 [BEING THE SEVENTEENTH ISSUE OF THE SERIES AND COMPLETING THE INDEX FOR THE PERIOD 1891-1907] COMPILED BY BERNARD GOMME PUBLISHED BY ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & COMPANY LTD 10, ORANGE STREET, LEICESTER SQUARE, W.C. UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES 1908 CONTENTS [Those Transactions for the first time included in the index are marked with an asterisk,* the others are continuations from the indexes of 1891-190G. Transactions included for the first time are indexed from 1891 onwards.} Anthropological Institute, Journal, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, Ireland, Proceedings of Royal Society, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, London, Proceedings of Royal Society, 2nd S. vol. xxi. pt. 2. Antiquaries, Newcastle, Procceedings of Society, vol. x., 3rd S. vol. ii. Antiquaries, Scotland, Proceedings of Society, vol. xli. Archaoologia ^Eliana, 3rd S. vol. iii. Archssologia Cambrensis, 6th S. vol. vii. Archaeological Institute, Journal, vol. Ixiv. Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire Archaeological Journal, vols. xii. (p. 97 to end), xiii. Biblical Archsoology, Society of, Proceedings, vol. xxix. Birmingham and Midland Institute, Transactions, vol. xxxii. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Transactions, vols. xxix. pt. 2, xxx. pt. 1 (to p. 179). British Academy, Proceedings, 1905 and 1900. British Archieological Association, Journal, N.S. vol. xiii. British Architects, Royal Institute of, Journal, 3rd S. vol. xiv. British Numismatic Journal, 1st S. vol. iii. British School at Athens, Annual, vol. xii. British School at Rome, Papers, vol. iv. Buckinghamshire Architectural and Archaeological Society, Records, vol. ix. pt. 4 (to p. 324). Cambridge Antiquarian Society, Transactions, vol. -

H/W Or CP) TRS None None S and H/W Or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd

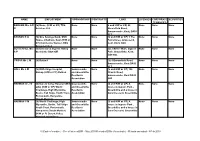

NAME EMPLOYMENT SPONSORSHIP CONTRACTS LAND LICENSES CORPORATE SECURITIES TENANCIES BARHAM Mrs A E (S) None, (H/W or CP) TRS None None S and H/W or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd. Broomfield Road, Swanscombe, Kent, DA10 0LT BASSON K G (S) One Savings Bank, OSB None None (S and H/W or CP) 1 The None None None House, Chatham, Kent.(H/W or Turnstones, Gravesend, CP) Call Centre Worker, RBS Kent, DA12 5QD Group Limited BUTTERFILL Mrs (S) Director at Ingress Abbey None None (S) 2 Meriel Walk, Ingress None None None S P Greenhthe DA9 9UR Park, Greenhithe, Kent, DA9 9GL CROSS Ms L M (S) Retired None None (S) 4 Broomfield Road, None None None Swanscombe, Kent DA10 0LT HALL Ms L M (S) NHS Kings Hospital, Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) 156 None None None Sidcup (H/W or CP) Retired and Greenhithe Church Road, Residents Swanscombe, Kent DA10 Association 0HP HARMAN Dr J M (S) Darent Valley Hospital (Mid- Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None wife) (H/W or CP) World and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Challenge, High Wycombe, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Bucks. Tall Ships Youth Trust, Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe Portsmouth, Hampshire (Youth Mentor) HARMAN P M (S) World Challenge, High Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None Wycombe, Bucks. Tall Ships and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Youth Trust, Portsmouth, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Hampshire (Youth Mentor) Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe (H/W or P) Darent Valley Hospital (midwifery) V:\Code of conduct - Dec of Interest\DPI - May 2015\Record of DPIs (for website) - PHarris amended - 8 Feb 2018 HARRIS PC (S) Retired. -

History from Old Site

I n the middle of the 19th century, following the introduction of competency exams in 1851, the need for pre-sea training was recognised for potential officers in the Royal and Merchant Navy. This led to a group of London ship owners founding the 'Thames Nautical Training College' in 1862. The Admiralty was approached for the loan of a suitable ship and was allocated the 'two-decker' HMS 'Worcester', a sister ship of the 'Trincomalee' (former 'Foudroyant') now restored and preserved at Hartlepool. At the time, the Royal Navy was starting to replace their fleet of 'wooden walls' with iron clad vessels. They had a vast surplus of such vessels and the 1473 ton 50 gun 'Worcester' was then laid up in the Nore. She had been built in Deptford Yard in 1843 and nearly £1,000 was spent on her conversion to a training ship prior to her being moved to her first base in Blackwall Reach. Within a year she was moved to Erith, thence in 1869 to Southend before finally moving in 1871 to what became a base forever associated with the 'Worcester' - the village of Greenhithe on the Kent shore and where successive ships remained until 1978. I ngress Abbey. Over fifty years passed before a permanent shore base was established in 1920, with the purchase of the Ingress Abbey estate which provided space for playing fields, offices, a sanatorium, laundry and a swimming pool. Starting with just 18 cadets, the numbers grew rapidly and there was soon a waiting list for entry. Official recognition soon followed - the Board of Trade allowed two years satisfactory 'Worcester' training to count in part towards a watchkeeping certificate, and in 1867 Queen Victoria instituted a Gold Medal for presentation annually. -

Relationship Between Transport and Development in the Thames Gateway

Relationship between transport and development in the Thames Gateway Contents Front cover......................................................................................................................2 Strategic overview and summary..................................................................................3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................8 2. The scope of the Thames Gateway in 2003 ............................................................11 3. Transport analysis....................................................................................................30 4. Potential scale of development ................................................................................34 5. Transport and development interaction ................................................................48 6. Strategic focus in the Thames Gateway .................................................................62 7. Phasing of transport and development...................................................................66 8. Conclusions ...............................................................................................................69 9. Appendix A: Travel characteristics and capacities...............................................72 10. Appendix B: Planning aspiration forecasts for SE sub areas ............................86 11. Appendix C: Examples from the Netherlands.....................................................89 12. Appendix -

The Services General for Surgical Practice

JAN. 26, 1946 OBITUARY MEDICAL JOURNAL tion in London in 1910 and president of the Otological Section later. After qualifying he held successivelv house posts at of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1915. Educated at the Morpeth Dispensary, Sheffield Royal Hospital, Sheffield General City of London School and St. Thomas's Hospital, he took Infirmary, and Essex and Colchester Hospital. In 1896 he the Conjoint ciplonias in 1897, the M.B.Lond. in 1899, and the settled in practice at Byfleet, Surrey, where he became medical B.S. two years later, and was admitted F.R.C.S. in 1902. His officer and public vaccinator to the Chertsey Union, and medical early posts at St. Thomas's were those of house-surgeon, house- officer to the Post Office. He moved to Sydenham in 1910, and physician, surgical registrar, and surgical tutor. Atter studying in 1914 became M.O.H. for Stevenage and assistant medical otology and rhinology at clinics in Germany he was elected inspector of schools for Hertfordshire. He served as a captain. aural surgeon to St. Thomas's in 1904, and held that post until in the R.A.M.C. in the war of 1914-18. He was for a time a his retirement in 1932. He was also aural surgeon to the member of the Lord Chancellor's Pension Appeal Board. Dr. London Fever Hospital for three years, and clinical teacher in Watson was the author of Handbook for Nurses, which passed otology and rhinology at the Royal Army Medical College. through eleven editions, Handbook for Senior Nurses and Mid- Marriage published a number of papers on his specialty in the wives, and Anaesthesia and Analgesia for Nurses and Midwvives. -

3818 Supplement to the London Gazette, 30 Maech, 1920

3818 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 30 MAECH, 1920. Miss Gladys Miargare.t Boyd. Louis Kirwan Brindley, Esq. Junior Administrative Assistant, War Works Managier and Deputy General Office. ' ' Manager., National' Filling Factory, Park Hugh Boyd, Esq. Royal, Ministry, of Munitions. Member of Belfast Local War Pensions William Brindley, Esq. Committee. Divisional Officer of Household Fuel and . Miss Katharine Faraday Boyd. Lighting Order Branch, Coal Mines Depart- Services in connection with War Refugees. ment, Board of Trade. Thomas Boydell, Esq. John Thomas Brinnand, Esq. Junior Inspector of Mines, Home Office. 'Chief 'Clerk, Shropshire Territorial Force Miss Irene Florinda Maud Boyle. Association. Temporary Clerk, Foreign Office, and Maud Isabel, Mrs. Brisley. British Delegation, Peace Conference. Divisional Secretary, Wandsworth Divi- Louise Judith, Lady Boyle. sion, British Red Cross iSoioiety. •Bed Cross Services, Third Avenue . Ernest 'George Brittain, Esq. Auxiliary Hospital, Hove. Technical Expert, Messrs. 'James .Spioer Percy Boyle, Esq. and Sons, Limited. •Traffic Ageint, Weyanouth, Gkreat'Western Charles Douglas Britten, Esq. ' Railway. Costings Investigation Department, Ad- Wallace Braby, Esq. miralty. Work in connection with Edith Cavell Reginald Wellesley Britten, Esq. Homes of Best for Nurses. Head of Division in War Trade Depart- Albert Edward Bradiburn, Esq. ment. Secretary, Cold Storage Department, Miss Elllen Alice Britton. Ministry of Food. Quartermaster, Tiverton Auxiliary Hos- Beryl Angelica Selby, ,Mrs. Bradford. pital', Devon. Cocntroller of Women Staff, Air Ministry. Miss Margaret Emily Broadbent. Miss Laura Katherine Bradshaw. Commandant and Officer in Charge, Rad- Senior Superintendent, London Diocesan don Court Auxiliary Hospital, Latchford, Rest Huts for Munition Workers. Cheshire. Ralph Hoilinshed Brady, Esq. Miss Anna Maria Hennen Broadwood. -

Uses of Historic Buildings for Residential Purposes (Colliers 2015)

= Use of Historic Buildings for Residential Purposes SCOPING REPORT – DRAFT 3 JULY 2015 PREPARED FOR HISTORIC ENGLAND COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL PROPERTY CONSULTANTS LIMITED Company registered in England and Wales no. 7996509 Registered office: 50 George St London W1U 7DY Tel: +44 20 7935 4499 www.colliers.com/uk [email protected] Version Control Status FINAL Project ID JM32494 Filename/Document ID Use of Historic Buildings for Residential 160615 Last Saved 23 October 2015 Owner David Geddes COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 2 of 66 use use of historic buildings for residential purposes DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 4 2 Literature Review 5 / 2.1 Introduction 5 2015 2.2 English Heritage / Historic England 5 - 10 - 2.3 General Issues 19 23 13:01 2.4 Case Study Orientated Books 21 2.5 Journal Articles 25 2.6 Architectural Journal Building Reports 25 3 Case Studies 26 4 Main Developers 53 4.1 Kit Martin CBE 53 4.2 Urban Splash 54 4.3 City and Country 55 4.4 PJ Livesey Group 57 4.5 Others 57 5 Conclusions 59 5.1 General 59 5.2 Country Houses 60 5.3 Large Instiutions 61 5.4 Mills and Factories 62 5.5 Issues that Could be Explored in Stage 2 62 COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 3 of 66 use use of historic buildings for residential purposes DRAFT 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this study is to investigate what might be done by the public sector to encourage conversion of large heritage assets at risk to residential use. It complements a survey that Historic England has commissioned of owners of historic buildings used for residential purposes, and also a review of the work of / Building Preservation Trusts in converting historic buildings for residential use. -

DEVELOPMENT CONTROL BOARD AGENDA Thursday 8 December 2005

DEVELOPMENTCONTROLBOARD AGENDA Thursday8December2005 GuidetotheAgenda 1. APOLOGIESFORABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONSOFINTEREST To receive any declarations of interest Members may wish to make including the term(s) of the Grant of Dispensation(s) by theStandardsCommittee. 3. CONFIRMATIONOFTHEMINUTESOFTHEMEETINGHELD (Pages3-10) ON10NOVEMBER2005 4. 05/00283/FUL (Pages11- FORMERWESTHILLHOSPITALSITE,WESTHILL, 28) DARTFORD BARRATTSOUTHLONDON Redevelopment of land to provide 239 residential units, including associated parking, open space, improved access arrangements, restoration of chapel to provide day nursery, conversionofpolicestationtoretailuse,newhealthcentreand Red Cross centre with associated parking & demolition of existingRedCrossbuilding. RECOMMENDATION: Refusal 5. 05/00516/FUL (Pages29- 39HIGHFIELDROAD,DARTFORD,KENT 38) NORTHWESTKENTMUSLIMASSOCIATION Application for the Variation of Condition 4 of Planning Permission DA/01/00276/COU in respect of increasing the numberofpersonsallowedfrom50to80personsonFridays between1200noon&1400hours. RECOMMENDATION: Refusal 1 6. 04/01247/FUL (Pages39- LANDSOUTHOFBOBDUNNWAYATTHEROUNDABOUT 48) JUNCTIONOPPOSITEJOYCEGREENLANE,DARTFORD GLAXOSMITHKLINEPLC ConstructionofanewlinkroadandaccessfromBobDunnWay roundabout,southtotheGlaxoSmithKlinesiteplusprovisionfor futureaccesstoJoyceGreenLane. RECOMMENDATION: Approval 7. 05/00968/FUL (Pages49- REARGARDENOF182HEATHLANE,DARTFORD,KENT 54) MRDFRY Erectionofaparttwo/partsinglestoreydetached3bedroom housewithassociatedcarparkingandlandscaping. -

Conservation Management Plans Relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016

Conservation Management Plans relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016 Site name Site location County Country Historic Author Date Title Status Commissioned by Purpose Reference England Register Grade Abberley Hall Worcestershire England II Askew Nelson 2013, May Abberley Hall Parkland Plan Final Higher Level Stewardship (Awaiting details) Abbey Gardens and Bury St Edmunds Suffolk England II St Edmundsbury 2009, Abbey Gardens St Edmundsbury BC Ongoing maintenance Available on the St Edmundsbury Borough Council Precincts Borough Council December Management Plan website: http://www.stedmundsbury.gov.uk/leisure- and-tourism/parks/abbey-gardens/ Abbey Park, Leicester Leicester Leicestershire England II Historic Land 1996 Abbey Park Landscape Leicester CC (Awaiting details) Management Management Plan Abbotsbury Dorset England I Poore, Andy 1996 Abbotsbury Heritage Inheritance tax exempt estate management plan Natural England, Management Plan [email protected] (SWS HMRC - Shared Workspace Restricted Access (scan/pdf) Abbotsford Estate, Melrose Fife Scotland On Peter McGowan 2010 Scottish Borders Council Available as pdf from Peter McGowan Associates Melrose Inventor Associates y of Gardens and Designed Scott’s Paths – Sir Walter Landscap Scott’s Abbotsford Estate, es in strategy for assess and Scotland interpretation Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff Wales (Awaiting details) 1997 Restoration Plan (Awaiting Rhondda Cynon Taff CBorough Council (Awaiting details) details) Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff -

7.2 Detailed Baseline

THE LONDON RESORT PRELIMINARY ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION REPORT Appendix 7.2 Detailed Baseline INTRODUCTION Chapter 7: Land use and socio-economics reports the existing socio-economic and employment conditions relevant to the study areas of the London Resort, and assesses the impact of the London Resort upon those baseline conditions. However, it is important to outline the baseline conditions in more detail than Chapter 7: Land use and socio-economics. This appendix reviews the baseline conditions at a more detailed geography and presents additional metrics and industry specific data. This appendix follows the same structure as the baseline presented in the chapter, where data relevant to each effect is listed in order of the effects assessed. Chapter 7: Land use and socio-economics concludes on the sensitivity of each receptor relevant to each effect, that sensitivity is not repeated in this appendix. The study areas are consistent with that presented in the main chapter, as shown in Table 7.2.1 below. Notably, the listed study area abbreviations are used throughout the appendix. Study areas considered in the London Resort Geographical Definition Rationale Study Area The DCO Order Limits. The PSB study area is used for effects which The Project Site Refer to Figure 7.1 in are at the Project Site level. It is used for the Boundary (PSB) Chapter 7 for a map of assessment of displacement / loss of the PSB businesses. The CIA is used to assess the displacement / loss of community uses, such as open spaces, Community A 500m radius around public rights of way and other recreational or Impact Area (CIA) the PSB community facilities as the community uses affected will be in or near the Project Site. -

Brochure PDF 00.Pdf

SUCCESS www.crestnicholson.com/thepier INGRESS PARK A SUCCESS STORY A new era continuing a legacy Crest Nicholson immediately appreciated the potential Public space has also been given careful consideration, of Ingress Park’s inspiring riverside location, knowing it and residents and visitors alike can enjoy a riverside could be developed into one of the premier residential piazza, grass amphitheatre and tree lined boulevard addresses in the south east. This is precisely what has leading down to the river. been achieved in the many years since work began here. Today, Ingress Park offers an unrivalled combination of The latest addition to the waterside phase at The Pier bespoke house designs in a spectacular 72-acre setting are Darbyshire and Oarmans Houses, sleek, modern that combines views of the Thames and parkland originally apartment buildings with many apartments affording landscaped by Capability Brown. spectacular dual aspect views. The centrepiece of the development is Ingress Abbey, built There is also private allocated parking and access via a lift in 1833 in ornate Gothic style. The abbey has been restored to your new apartment, as well as secure cycle storage in to its former grandeur and is now used for commercial the basement. purposes. However, it is not the only reminder of the location’s past; in the grounds, the original follies have Ingress Park is now close to completion, and this multi also been rediscovered and cleared of overgrown foliage: award-winning regeneration has become a highly they now form part of the Heritage Trail at Ingress Park. sought after residential location and a well-established community. -

Notes from the Unpublished Papers of Dorothy Stroud

A list of landscapes that have been attributed to ‘Capability’ Brown This list, now in its fifth edition(16th December, 2016), has been compiled by John Phibbs from the work of others, primarily Dorothy Stroud, but also David Brown, Karen Lynch, Nick Owen, Susanne Seymour, Roger Turner, Peter Willis, and, in particular, my collaborator, Steffie Shields, who has checked and added to its drafts. The lists have also been shown to and commented on by the County Gardens Trusts. Great credit is due to all parties for their help. The list of attributions to Brown has elicited a good deal of correspondence for which I am very grateful, and among many others, thanks are due to Don Josey, Surrey Gardens Trust; Terence Reeves-Smyth and Patrick Bowe from Ireland; S.V.Gregory, Staffordshire Gardens Trust; Joanna Matthews, Oxfordshire Gardens Trust; Christine Hodgetts, Warwickshire Gardens Trust; the Dorset Gardens Trust; Kate Harwood, Hertfordshire Gardens Trust; Val Bott, Susan Darling and Barbara Deason, London Parks & Gardens Trust; Janice Bennetts, Wendy Bishop, Michael Cousins, Dr Patrick Eyres, Jane Furze, Tony Matthews, Jenifer White and Min Wood. Many correspondents have written with material about what Brown might have done at various places. I have to emphasise that the attributions list attempts to include all the places where he might have offered advice. It asks neither whether that advice was acted on, nor whether he was paid. The determination of what might have been done at any of these places is a distinct process and will always be open to question. The aim of this list is to assess the likelihood of each and all of the attributions that have been made to Brown.