Relationship Between Transport and Development in the Thames Gateway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Representations and Evidence Received

CAP 1134 Appendix A: List of representations and evidence received APPENDIX A List of representations and evidence received Responses submitted in response to the Gatwick: Market Power Assessment, the CAA’s Initial Views – February 20121 . David Starkie, regulatory and competition economist . Gatwick Airport Limited (GAL) . Virgin Atlantic Airways (VAA) Responses submitted in response to the Consultation on Gatwick Market Power Assessment (CAP 1052)2 . British Airways (BA) . easyJet . GAL . Gatwick Airport Consultative Committee . VAA Stakeholder meetings / teleconference held3 Airlines . Aer Lingus . Air Asia X . Air Berlin . Air Malta . Aurigny 1 Non-confidential versions of these submissions are available on the CAA's website. 2 Non-confidential versions of these submissions are available on the CAA's website. 3 Included in this are airlines that met the CAA Board as part of the consultation process. 1 CAP 1134 Appendix A: List of representations and evidence received . BA . bmi regional . Cathay Pacific . Delta . easyJet . Emirates . Flybe . Jet2 . Lufthansa . Monarch . Norwegian Air Shuttle . Ryanair . Thomas Cook . TUI Travel . VAA . Wizz Air Airport operators: . Birmingham Airport Holdings Limited . East Midlands International Airport Limited . Gatwick Airport Limited . Heathrow Airport Limited . London Luton Airport Operations Limited . London Southend Airport Company Limited . Manchester Airports Group PLC . Stansted Airport Limited 2 CAP 1134 Appendix A: List of representations and evidence received Cargo carriers . British Airways World Cargo . bmi Cargo . DHL . Emirates Sky Cargo . FedEx . Royal Mail . TNT Express Services . [] Other stakeholders . Agility Logistics . Airport Coordination Limited UK . Gatwick Airport Consultative Committee . Stop Stansted Expansion Information gathered under statutory powers (section 73 Airports Act 1986 / section 50 Civil Aviation Act 2012) . -

Archaeological Papers Published

INDEX OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PAPERS PUBLISHED IN 1907 [BEING THE SEVENTEENTH ISSUE OF THE SERIES AND COMPLETING THE INDEX FOR THE PERIOD 1891-1907] COMPILED BY BERNARD GOMME PUBLISHED BY ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & COMPANY LTD 10, ORANGE STREET, LEICESTER SQUARE, W.C. UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES 1908 CONTENTS [Those Transactions for the first time included in the index are marked with an asterisk,* the others are continuations from the indexes of 1891-190G. Transactions included for the first time are indexed from 1891 onwards.} Anthropological Institute, Journal, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, Ireland, Proceedings of Royal Society, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, London, Proceedings of Royal Society, 2nd S. vol. xxi. pt. 2. Antiquaries, Newcastle, Procceedings of Society, vol. x., 3rd S. vol. ii. Antiquaries, Scotland, Proceedings of Society, vol. xli. Archaoologia ^Eliana, 3rd S. vol. iii. Archssologia Cambrensis, 6th S. vol. vii. Archaeological Institute, Journal, vol. Ixiv. Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire Archaeological Journal, vols. xii. (p. 97 to end), xiii. Biblical Archsoology, Society of, Proceedings, vol. xxix. Birmingham and Midland Institute, Transactions, vol. xxxii. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Transactions, vols. xxix. pt. 2, xxx. pt. 1 (to p. 179). British Academy, Proceedings, 1905 and 1900. British Archieological Association, Journal, N.S. vol. xiii. British Architects, Royal Institute of, Journal, 3rd S. vol. xiv. British Numismatic Journal, 1st S. vol. iii. British School at Athens, Annual, vol. xii. British School at Rome, Papers, vol. iv. Buckinghamshire Architectural and Archaeological Society, Records, vol. ix. pt. 4 (to p. 324). Cambridge Antiquarian Society, Transactions, vol. -

Tfl RIVER CROSSINGS CONSULTATION EXERCISE and the REDBRIDGE RESPONSE: BRIEFING PAPER

TfL RIVER CROSSINGS CONSULTATION EXERCISE AND THE REDBRIDGE RESPONSE: BRIEFING PAPER 1. Overview Building upon previous consultations, Transport for London is presently undertaking a public consultation exercise seeking views upon a revised set of options for new crossings of the River Thames east of Silvertown. (A proposed new tunnel under the Thames linking Silvertown with the North Greenwich peninsular has already attracted support and will be the subject of separate consultation later this year). The four options upon which views are now sought comprise: A new modern ferry at Woolwich A ferry service at Gallions Reach A bridge at Gallions Reach A bridge at Belvedere. The location of these options is shown in Appendix A in a separate document accompanying this one. For each separate proposal, views are invited whether respondents Strongly Support/Support/Neither/ Oppose/ Strongly Oppose. The public consultation deadline is 12th September, but Boroughs have been given until 30th September to respond. The purpose of this paper is to draw attention to this consultation, summarise broadly the features of the emerging options and to seek a steer on the stance to be followed in LB Redbridge’s formal reply. 2. Background It is important to be aware of previous formal LB Redbridge positions conveyed to TfL in respect of new river crossings proposals. Those stances are summarised in Appendix B to this paper. The salient context surrounding the options now being considered is summarised below: TfL consultation in recent years has yielded support from a majority of respondents to provision of new Thames crossings, with businesses in east and south-east London very supportive. -

London Southend Airport

LONDON SOUTHEND AIRPORT NOISE ACTION PLAN Adopted by the Secretary of State for Environment Food and Rural Affairs March 2012 CONTENTS Section Page INTRODUCTION 1 STRATEGIC NOISE MAPPING 2006 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE AIRPORT 2 THE AUTHORITY RESPONSIBLE 3 THE LEGAL CONTEXT 3 International and National Regulatory Framework for Aircraft 3 Noise Local Policy Framework 5 EXISTING NOISE LIMITS 5 The Lease 5 Planning Conditions 6 Noise Abatement Procedures 6 SUMMARY OF THE RESULTS OF NOISE MAPPING 7 EVALUATION OF THE ESTIMATED NUMBER OF PEOPLE 10 EXPOSED TO NOISE, IDENTIFICATION OF PROBLEMS AND SITUATIONS THAT NEED TO BE IMPROVED PUBLIC CONSULTATION 11 EXISTING AND FUTURE NOISE REDUCTION MEASURES 13 FINANCIAL INFORMATION 16 EVALUATION 17 EXPECTED OUTCOME 17 APPENDIX A DEFRA Noise Maps 18 INTRODUCTION 1 This Noise Action Plan has been prepared in accordance with the Environmental Noise (England) Regulations 2006 (as amended) (the “Regulations”). These Regulations transposed the EU Environment Noise Directive (2002/49/EC), known as END, relating to the assessment and management of environmental noise into UK legislation and make the preparation of a Noise Action Plan for a number of different noise sources, including airports, a legal requirement. 1 2 Government, through the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), issued guidelines in March 2009 to airport operators to explain how to prepare Noise Action Plans. The guidelines are detailed and airport operators must have regard to them in drawing up their Noise Action Plans. The sections in this Noise Action Plan follow those suggested in the guidelines. The guidelines also outline the requirements for consulting on the draft plans. -

Fastrack B Gravesend to Temple Hill Via Bluewater Shopping Centre - Valid from Sunday, August 29, 2021 to Thursday, November 11, 2021

Fastrack B Gravesend to Temple Hill via Bluewater Shopping Centre - Valid from Sunday, August 29, 2021 to Thursday, November 11, 2021 Monday to Friday - Gravesend Garrick Street B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B Temple Hill Joyce Green Lane Terminus 0528 0558 0622 0642 0657 0707 0718 0729 0741 0754 0807 0820 0833 0845 0857 0908 0918 0928 0940 0950 1000 1010 1020 Dartford Home Gardens 0539 0609 0634 0654 0712 0723 0735 0747 0759 0811 0823 0835 0848 0900 0911 0921 0931 0941 0951 1001 1011 1021 1031 Dartford Darent Valley Hospital 0550 0620 0645 0705 0724 0736 0748 0800 0812 0824 0836 0848 0901 0913 0923 0933 0943 0953 1003 1013 1023 1033 1043 Bluewater Bus Station 0555 0625 0651 0711 0731 0743 0755 0807 0819 0831 0843 0855 0907 0919 0929 0939 0949 0959 1009 1019 1029 1039 1049 Greenhithe Railway Station 0600 0630 0656 0716 0736 0748 0800 0812 0824 0836 0847 0859 0911 0923 0933 0943 0953 1003 1013 1023 1033 1043 1053 Ingress Park Ingress Abbey 0602 0632 0659 0719 0740 0751 0803 0815 0827 0838 0849 0901 0913 0925 0935 0945 0955 1005 1015 1025 1035 1045 1055 Swanscombe The George and Dragon 0607 0637 0704 0725 0747 0758 0809 0820 0832 0843 0853 0905 0917 0929 0939 0949 0959 1009 1019 1029 1039 1049 1059 Ebbsfleet International Railway Station 0614 0644 0711 0732 0754 0805 0816 0827 0839 0850 0900 0911 0923 0935 0945 0955 1005 1015 1025 1035 1045 1055 1105 Gravesend Garrick Street 0623 0653 0721 0742 0804 0816 0828 0838 0850 0901 0911 0921 0932 0944 0954 1004 1014 1024 1034 1044 1054 1104 1114 B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B -

Buses As Rapid Transit

BBuusseess aass RRaappiidd TTrraannssiitt A transport revolution in waiting WWeellccoommee ttoo BBRRTT--UUKK RT is a high profile rapid transit mode that CONTACT BRT-UK combines the speed, image and permanence of The principal officers of BRT-UK are: light rail with the cost and flexibility of bus. BRT-UK Chair: Dr Bob Tebb Bseeks to raise the profile of, and develop a centre b of excellence in, bus rapid transit. b Deputy Chair: George Hazel BRT-UK does not seek to promote bus-based rapid transit b Secretary: Mark Curran above all other modes. BRT-UK seeks to enhance b Treasurer: Alex MacAulay understanding of bus rapid transit and what it can do, and b Membership: Dundas & Wilson allow a fair and informed comparison against other modes. External promotion: George Hazel BRT-UK is dedicated to the sharing of information about b evolving bus-based rubber-tyred rapid transit technology. b Website: Alan Brett For more information please contact us at [email protected]. b Conference organisation: Bob Menzies ABOUT BRT-UK BRT-UK MEMBERSHIP Membership of BRT-UK has been set at £250 for 2007/08. Objectives of the association Membership runs from 1st April-31st March. Membership is payable by cheque, to BRT-UK. Applications for membership The objectives of BRT-UK are: should be sent to BRT-UK, c/o Dundas & Wilson, 5th Floor, b To establish and promote good practice in the delivery Northwest Wing, Bush House, Aldwych, London, WC2B 4EZ. of BRT; For queries regarding membership please e-mail b To seek to establish/collate data on all aspects of BRT -

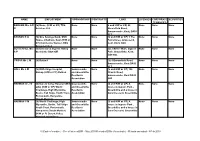

H/W Or CP) TRS None None S and H/W Or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd

NAME EMPLOYMENT SPONSORSHIP CONTRACTS LAND LICENSES CORPORATE SECURITIES TENANCIES BARHAM Mrs A E (S) None, (H/W or CP) TRS None None S and H/W or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd. Broomfield Road, Swanscombe, Kent, DA10 0LT BASSON K G (S) One Savings Bank, OSB None None (S and H/W or CP) 1 The None None None House, Chatham, Kent.(H/W or Turnstones, Gravesend, CP) Call Centre Worker, RBS Kent, DA12 5QD Group Limited BUTTERFILL Mrs (S) Director at Ingress Abbey None None (S) 2 Meriel Walk, Ingress None None None S P Greenhthe DA9 9UR Park, Greenhithe, Kent, DA9 9GL CROSS Ms L M (S) Retired None None (S) 4 Broomfield Road, None None None Swanscombe, Kent DA10 0LT HALL Ms L M (S) NHS Kings Hospital, Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) 156 None None None Sidcup (H/W or CP) Retired and Greenhithe Church Road, Residents Swanscombe, Kent DA10 Association 0HP HARMAN Dr J M (S) Darent Valley Hospital (Mid- Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None wife) (H/W or CP) World and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Challenge, High Wycombe, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Bucks. Tall Ships Youth Trust, Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe Portsmouth, Hampshire (Youth Mentor) HARMAN P M (S) World Challenge, High Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None Wycombe, Bucks. Tall Ships and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Youth Trust, Portsmouth, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Hampshire (Youth Mentor) Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe (H/W or P) Darent Valley Hospital (midwifery) V:\Code of conduct - Dec of Interest\DPI - May 2015\Record of DPIs (for website) - PHarris amended - 8 Feb 2018 HARRIS PC (S) Retired. -

London, a World-Class City an Introduction to the Berkeley Group

LONDON, A WORLD-CLASS CITY AN INTRODUCTION TO THE BERKELEY GROUP Our ambition on every site is to create a beautiful, successful place. TONY PIDGLEY, CBE CHAIRMAN, THE BERKELEY GROUP 2 LONDON, A WORLD-CLASS CITY London is an extraordinary city, a magnet for people I believe it’s the talent of our architects and the and a hub of creativity and enterprise. Its architecture clients who commission them that keeps London and public spaces play a huge part in this appeal. fresh. Together they continually create places that They define the ‘picture postcard’ view that makes flex to the changing needs of our workforce, our London such a big draw for visitors. education, and our lifestyles. Yet it is the city’s ability to refresh and renew itself, The best new development has a great sense of respect blending contemporary buildings and public realm for London’s neighbourhoods. Despite all the pressures with the historic fabric, that is so intrinsic to its that come with growth, it recognizes that we are drawn success. International headquarters sit alongside to beautiful, sociable spaces. Places that feel authentic Elizabethan pubs and modern homes. You find arts and truly designed for people. venues forged from heritage buildings to make Today, neighbourhoods throughout London are set space for our contemporary creative spirit. to change, driven by the urgency of providing more Above all, London remains a collection of villages. homes for everyone within a finite footprint. The quality Neighbourhood shops and restaurants, local parks and of architecture and new development always matters. attractions, all produce a global world city and yet still But perhaps now more than ever, it seems to me feel intimate, local and familiar at the same time. -

'Ungovernable'? Financialisation and the Governance Of

Governing the ‘ungovernable’? Financialisation and the governance of transport infrastructure in the London ‘global city-region’ February 2018 Peter O’Briena* Andy Pikea and John Tomaneyb aCentre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS), Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK NE1 7RU. Email: peter.o’[email protected]; [email protected] bBartlett School of Planning, University College London, Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, 620 Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London, UK WC1H 0NN. Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author 1 Abstract The governance of infrastructure funding and financing at the city-region scale is a critical aspect of the continued search for mechanisms to channel investment into the urban landscape. In the context of the global financial crisis, austerity and uneven growth, national, sub-national and local state actors are being compelled to adopt the increasingly speculative activities of urban entrepreneurialism to attract new capital, develop ‘innovative’ financial instruments and models, and establish new or reform existing institutional arrangements for urban infrastructure governance. Amidst concerns about the claimed ‘ungovernability’ of ‘global’ cities and city-regions, governing urban infrastructure funding and financing has become an acute issue. Infrastructure renewal and development are interpreted as integral to urban growth, especially to underpin the size and scale of large cities and their significant contributions within national economies. Yet, oovercoming fragmented local jurisdictions to improve the governance and economic, social and environmental development of major metropolitan areas remains a challenge. The complex, and sometimes conflicting and contested inter-relationships at stake raise important questions about the role of the state in wrestling with entrepreneurial and managerialist governance imperatives. -

London City Airport Master Plan 2006

Master Plan November 2006 Master Plan November 2006 At a more local level, the Airport is a force restrictions we impose will continue. Foreword for regeneration which has not only created Alongside this the opening of the extension jobs and prosperity in the immediate area, of the DLR to the Airport in December but has also helped to spearhead the 2005 means we now have significantly success of landmarks like Canary Wharf improved public transport links with a and ExCel London and drive recent and higher proportion of passengers (49%) future extensions to the Docklands Light accessing the Airport by rail than any other Railway (DLR). UK airport. These links will be strengthened further by the operation of Crossrail in the We are also very well placed to continue future, and LCA is a key supporter of this to drive the economic prosperity flowing project. from the London Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2012. Through co-operating with a wide variety of interested bodies, we will seek to further But to do all this, we need to grow. In improve our already good environmental 2003 the Government published its Aviation record concentrating on reducing our White Paper which required all UK airports contribution to climate change and man- to set out master plans to grow through to aging all emissions, particularly waste. In 2030 to meet the increase in passenger addition, we support the aviation industry’s demand. One of the key objectives of this inclusion in the EU Emissions Trading paper was to maximise the use of existing Scheme, which will allow the issue of runways and infrastructure to delay, aviation greenhouse gas emissions to be reduce and in some cases eliminate the effectively and responsibly addressed. -

Opportunity and Intensification Areas – 2009 Compared with 2008 London Plan

Opportunity and Intensification Areas – 2009 compared with 2008 London Plan Opportunity Areas – Policy Comparison The policies for the Opportunity and Intensification Areas are broadly similar for both the 2008 and 2009 London Plans. The differences are as follows: In the 2008 plan the areas are structured and broken down into the relevant sub-regional areas and form part of sub-regional policy, whereas in the updated plan there is a single table provided which covers all of the areas. The 2009 London Plan omits references to, “deliver good design, including public realm, open space and where appropriate, tall buildings.” In the 2008 Plan authorities should “seek to exceed” minimum housing targets for relevant sites whereas the 2009 Plan refers to “optimizing density” and “contributing to meeting the minimum guidelines”. This change of approach may account for some of the alterations in housing projections for some of the sites, both upwards and downwards. Map of Opportunity and Intensification Areas – 2009 London Plan Map of Opportunity and Intensification Areas – 2008 London Plan Comparison of Targets for Employment and Housing in Intensification Areas, 2008 versus 2009 London Plan Area 2008 London Plan 2009 London Plan Change Housing Housing Minimum Minimum Homes 2001 - 2026 Canada Water/Surrey Quays 2000 2500 +500 Dalston N/A 1700 +1700 Farringdon/Smithfield 100 1000 +900 Haringey Heartlands/Wood Green 1700 1000 -700 Harrow and Wealdstone N/A 1500 +1500 Holborn 200 200 0 Kidbrooke 2400 4400 +2000 Mill Hill East 3500 2100 -1400 -

Camilla Ween Lessons from London

Camilla Ween Lessons from London Harvard Loeb Fellow February 2008 1 Developing a World City 2 Better integration of the River Thames 3 Planning for growth 4 Balancing new and old 5 2000 London changed! Greater London Authority Mayor Ken Livingstone 6 Greater London Authority: • Mayor’s Office • Transport for London • London Development Agency • Fire and Emergency Planning • Metropolitan Police 7 What helped change London • Greater London Authority established in 2000 • Spatial Development Strategy - London Plan • Transport for London • Congestion Charge Scheme • Major transport schemes • Role of Land Use Planning • Sustainable travel and ‘soft’ measures 8 Spatial Development Strategy 9 London Plan A coherent set of policies • Climate Change Action Plan • Waste • Noise • Biodiversity • Children’s play space • Flood • Access etc etc 10 11 Transport for London • Overground rail • Underground • Buses • Trams • Taxis • River Services • Cycling • Walking 12 Transport for London • Budget ca $15 Bn • Carries 3 billion passengers pa 13 Transport for London Steady increase in journeys (2007): • Bus up 3.6% • Underground up 4.5% • Docklands Light Rail 16% 14 Transport Strategy 15 Congestion Charge Scheme • First zone introduced 2003 • Area doubled 2007 16 16 Congestion Charging 17 17 Congestion Charge Scheme • Number-plate recognition • Central call-centre billing • Many options for paying: - Buy on the day - Text messaging - Internet 18 Congestion Charging • $16 per day (multiple re-entry) • 7.00 am to 6.00 pm • Monday to Friday • Weekends free 19 Congestion Charging Benefits: • 21 % Traffic reduction • 30% Congestion reduction in first year • 43 % increase in cycling within zone • Reduction in Accidents • Reduction in key traffic pollutants • $250m raised for improving transport 20 Congestion Charging • Public transport accommodating displaced car users • Retail footfall higher than rest of UK • No effect on property prices 21 Major Transport Schemes Being developed: • Crossrail • New tram systems • Major interchanges - e.g.