Contextualizing Sabahattin Ali's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond

m Mittelpunkt dieses Bandes steht das Werk des türkischen Autors und Übersetzers aus dem Deutschen Sabahattin Ali, der mit seinem Roman KürkI Mantolu Madonna (Die Madonna im Pelzmantel) zu posthumem Ruhm gelangte. Der Roman, der zum Großteil in Deutschland spielt, und andere seiner Werke werden unter Aspekten der Weltliteratur, (kultureller) Übersetzung und Intertextualität diskutiert. Damit reicht der Fokus weit über die bislang im Vordergrund stehende interkulturelle Liebesgeschichte 2016 Türkisch-Deutsche Studien in der Madonna hinaus. Weitere Beiträge beschäftigen sich mit Zafer Şenocaks Essaysammlung Jahrbuch 2016 Deutschsein und dem transkulturellen Lernen mit Bilderbüchern. Ein Interview mit Selim Özdoğan rundet diese Ausgabe ab. The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond herausgegeben von Şeyda Ozil, Michael Hofmann, Jens-Peter Laut, Yasemin Dayıoğlu-Yücel, Cornelia Zierau und Kristin Dickinson Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch ISBN: 978-3-86395-297-6 Universitätsverlag Göttingen ISSN: 2198-5286 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Şeyda Ozil, Michael Hofmann, Jens-Peter Laut, Yasemin Dayıoğlu-Yücel, Cornelia Zierau, Kristin Dickinson (Hg.) The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch 2016 erschienen im Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2017 The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond Herausgegeben von Şeyda Ozil, Michael Hofmann, Jens-Peter Laut, Yasemin Dayıoğlu-Yücel, Cornelia Zierau und Kristin Dickinson in Zusammenarbeit mit Didem Uca Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch 2016 Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2017 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.dnb.de> abrufbar. Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. -

Literary Translation from Turkish Into English in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 1990-2010

LITERARY TRANSLATION FROM TURKISH INTO ENGLISH IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND IRELAND, 1990-2010 a report prepared by Duygu Tekgül October 2011 Making Literature Travel series of reports on literary exchange, translation and publishing Series editor: Alexandra Büchler The report was prepared as part of the Euro-Mediterranean Translation Programme, a co-operation between the Anna Lindh Euro-Mediterranean Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures, Literature Across Frontiers and Transeuropéenes, and with support from the Culture Programme of the European Union. Literature Across Frontiers, Mercator Institute for Media, Languages and Culture, Aberystwyth University, Wales, UK This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. 1 Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 4 1.1 Framework .......................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Method and scope ................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Conclusions ......................................................................................................... 5 1.3.1 Literary translation in the British Isles ................................................................... 5 1.3.2 Literature translated from Turkish – volume and trends .............................................. 6 1.3.3 Need for reliable data on published translations -

Istanbul: Memories and the City Genre: Memoir

www.galaxyimrj.com Galaxy: An International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ISSN: 2278-9529 Title of the Book: - Istanbul: Memories and the City Genre: Memoir. Author: Orhan Pamuk. Paperback: 400 pages. Publisher: Vintage; Reprint edition (11 July 2006). Language: English. Reviewed By: Syed Moniza Nizam Shah Research Scholar Department of English University of Kashmir Turkey’s only Nobel Prize laureate (till date) Orhan Pamuk is undoubtedly one of the most significant and a widely debated novelist of the contemporary world literature. Seldom does a novelist in his fifties merit and receive the kind of critical attention that has come to Orhan Pamuk. He is the bestselling novelist in contemporary Turkey. His novels have been studied meticulously by critics such as Maureen Freely, MehnazM.Afridi, ErdağGöknar, Kader Konuk, SibelErol et al. Pamuk was born in a Muslim family in Nistantasi, a highly Westernized district in Istanbul. He was educated at Roberts College, the elite, secular American high school in Istanbul, a city which bifurcates or connects Asia and Europe. Presently, he is a professor in the Humanities at Columbia University, where he teaches comparative literature and writing. His upbringing and schooling in a highly secularized Istanbul made him a typical Istanbul like man who is torn between the traditional values of the city (century’s old Ottoman culture) and Kemalist Cultural ideology/Kemalism. Pamuk is deeply attached to his city—Istanbul, where he was born and breaded and continues to live in. Whether Pamuk is writing about the contemporary Turkey as in The Museum of Innocence or historical times as in My Name is Red, the city of Istanbul has almost been the main character/setting in his novels. -

1.Sınıf AKTS Bilgileri

Dersin Dönemi: 1. Yarıyıl Dersin Kodu Dersin Adı T U K AKTS OZ101 Türk Dili I 2 0 2 2 Ders İçeriği: Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı ile ilgili konular DERS BİLGİLERİ Ders Adı Kodu Yarıyıl T+U Kredi AKTS Saat Türk Dili I OZ101 1 2+0 2 2 Ön Koşul Dersleri - Dersin Dili Türkçe Dersin Seviyesi Lisans Dersin Türü Zorunlu Dersin Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Koordinatörü Dersi Verenler Dr. Öğr Dersin Yok Yardımcıları Bu dersin amacı öğrencilerin ana dilleri Türkçeyi düzgün ve kurallarına uygun olarak sözlü ve yazılı ifadede en etkin bir biçimde kullanmasına yardımcı olmaktır. Dil bilinci kazandırmanın yanı sıra ders, öğrencilere Dersin Amacı Türk edebiyatı hakkında bilgi vermeyi; edebi türlerden örneklerle öğrencinin metin analizi yapma, yorumlama ve eleştirel düşünme becerisini geliştirmeyi hedeflemektedir. Dersin İçeriği Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı ile ilgili konular Dersin Öğrenme Çıktıları DERS İÇERİĞİ Hafta Konular Ön Hazırlık Dil Hakkında Genel Bilgi Dil nedir, dilin doğuşu, dil ve 1 iletişim, dil ve düşünce, dil ve toplum, dil ve kültür. 2 Dil Bilgisi Ses Bilgisi 3 Dil Bilgisi Yazım Kuralları 4 Dil Bilgisi Noktalama İşaretleri 5 Dil Bilgisi Anlatım Bozuklukları Türkçe Kültürü “Türkçe Üzerine”, Alev Alatlı 6 “Değişen Türkçemiz” “Türkçe Sorunu”, Murat Belge Türkçe Kültürü “Türkçenin Geleceği”, Hayati Develi “Türkçenin Güncel Sorunları”, Prof. Dr. Cahit 7 KAVCAR “Türkçenin Güncel Sorunları”, Prof. Dr. Şükrü Haluk Akalın 8 ARA SINAV Hikâye Kültürü “Pandomima”, Sami Paşazade Sezai “Ecir ve Sabır”, Hüseyin 9 Rahmi Gürpınar “Ferhunde Kalfa”, Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil Hikâye -

Faculty of Humanities

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES The Faculty of Humanities was founded in 1993 due to the restoration with the provision of law legal decision numbered 496. It is the first faculty of the country with the name of The Faculty of Humanities after 1982. The Faculty started its education with the departments of History, Sociology, Art History and Classical Archaeology. In the first two years it provided education to extern and intern students. In the academic year of 1998-1999, the Department of Art History and Archaeology were divided into two separate departments as Department of Art History and Department of Archaeology. Then, the Department of Turkish Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 1999-2000 , the Department of Philosophy was founded in the academic year of 2007-2008 and the Department of Russian Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 2010- 2011. English prep school is optional for all our departments. Our faculty had been established on 5962 m2 area and serving in a building which is supplied with new and technological equipments in Yunusemre Campus. In our departments many research enhancement projects and Archaeology and Art History excavations that students take place are carried on which are supported by TÜBİTAK, University Searching Fund and Ministry of Culture. Dean : Vice Dean : Prof. Dr. Feriştah ALANYALI Vice Dean : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Erkan İZNİK Secretary of Faculty : Murat TÜRKYILMAZ STAFF Professors: Feriştah ALANYALI, H. Sabri ALANYALI, Erol ALTINSAPAN, Muzaffer DOĞAN, İhsan GÜNEŞ, Bilhan -

Ova, Ali Asker-Yüksek Lisans.Pdf

i T.C. ARDAHAN ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ TÜRK D İLİ VE EDEB İYATI ANAB İLİM DALI GAR İP Şİİ R AKIMI: İLKELER İN Şİİ RE YANSIMASI Ali Asker OVA YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ Ardahan-2016 ii T.C. ARDAHAN ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ TÜRK D İLİ VE EDEB İYATI ANAB İLİM DALI GAR İP Şİİ R AKIMI: İLKELER İN Şİİ RE YANSIMASI YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ Ali Asker OVA Yrd. Doç. Dr. Vedi A ŞKARO ĞLU Ardahan-2016 i ii iii ÖNSÖZ Tüm süreç boyunca beni bir an olsun yalnız bırakmayan değerli e şim Dr. Fatima Ova'ya; meslek hayatım boyunca bana rehberlik eden ve uzun yıllardır dostlu ğunu esirgemeyen, bu çalı şmada da bana yol gösteren ö ğretmen arkada şım Cafer Yıldırım'a; akademik hayata ilk adımlarımı atarken deste ğini hiçbir zaman esirgemeyen sevgili hocam, a ğabeyim Yrd. Doç. Dr. O ğuz Şim şek'e; yüksek lisans e ğitimim boyunca bana daima yol gösteren Ardahan Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Sekreteri Selma Akyol'a; bu çalı şmamla beni ı şığa karı ştıran de ğerli danı şman hocam, üstadım Yrd. Doç. Dr. Vedi A şkaro ğlu'na sonsuz te şekkürlerimi sunarım. iv ÖZET İnsan, edebiyatın merkezindeki konumunu tarih sahnesinde kimi zaman kaybetmi ş, kimi zaman da yeniden kazanmı ştır. Edebi akımlar, do ğa, kültür, estetik, bakı ş açısı ve dil gibi pek çok unsura ba ğlı olarak kendilerini tanımlama yoluna gitmi şlerdir. Sanatın ne şekilde algılandı ğı ve eserlerin üretim tarzı genellikle poetika adı verilen bazen açık bir manifesto ile ortaya serimlenen bazen de dolaylı bir biçimse sadece sanatsal üretimlerle kendini ortaya konan ilkelere göre adlandırılır ve geli şimini gösterir. -

My Father's Suitcase

My Father’s Suitcase 1 My Father’s Suitcase First Published in 2007 by Route www.route-online.com PO Box 167, Pontefract, WF8 4WW, UK e-mail: [email protected] Byteback book number 16 BB016 The text included here is used with kind permission from the Nobel Foundation. Text © The Nobel Foundation 2006. Translation from Turkish by Maureen Freely Further presentations and lectures by Nobel Prize recipients can be found on the website www.nobelprize.org Full details of the Route programme of books can be found on our website www.route-online.com Route is a fiction imprint of ID Publishing www.id-publishing.com All Rights Reserved This book is restricted to use by download from www.route-online.com No reproduction of this text in any other form of publication is allowed without written permission This publication was supported by Arts Council England 2 My Father’s Suitcase Contents Orhan Pamuk 4 Bibliographical Notes My Father’s Suitcase 7 The Nobel Lecture Orhan Pamuk’s Works 22 3 My Father’s Suitcase Orhan Pamuk Biographical Notes Orhan Pamuk was born 7 June 1952 in Istanbul into a prosperous, secular middle-class family. His father was an engineer as were his paternal uncle and grandfather. It was this grandfather who founded the family’s fortune. Growing up, Pamuk was set on becoming a painter. He graduated from Robert College then studied architecture at Istanbul Technical University and journalism at Istanbul University. He spent the years 1985-1988 in the United States where he was a visiting researcher at Columbia University in New York and for a short period attached to the University of Iowa. -

Madonna in a Fur Coat Free

FREE MADONNA IN A FUR COAT PDF Sabahattin Ali,Maureen Freely,Alexander Dawe | 176 pages | 05 May 2016 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780241206195 | English | London, United Kingdom Madonna in a Fur Coat Summary & Study Guide Published to a muted response in Turkey in the s, was revived there more than three years ago and has remained a bestseller ever since. And even if you do see it all, and there are tiny holes here and there, it will not diminish the delight of reading this classic of modern Turkish literature, which although first published to a muted response in Turkey in the s was revived there more than three years ago and has remained a bestseller ever since. It resonates with literary allusions and has a message that Turkish youth has apparently adopted with rare fervour. Sabahattin Ali may not be the most familiar of literary figures to western readers, but he was a major voice in 20th-century Turkey as a newspaper owner and editor. He was highly political, suffered imprisonment for sedition and was deemed sufficiently dangerous by the authorities to have been murdered in while crossing the border into Bulgaria, possibly during interrogation by the national secret service. No one knows what really happened, nor have the whereabouts of his remains ever Madonna in a Fur Coat located. Considering his background as a socialist dissident, Ali may not seem the most likely author of this gorgeously melancholic romance featuring a timid antihero and an infuriatingly independent femme fatale with a world-weary attitude to the ways of men. -

How Could the Popularity of Kürk Mantolu Madonna in Turkey Over the Last Decade Be Explained?

How could the popularity of Kürk Mantolu Madonna in Turkey over the last decade be explained? Jirapon Boonpor S1653032 MA Middle Eastern Studies Professor Dr Erik-Jan Zürcher Leiden University Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One Kürk Mantolu Madonna’s Past Receptions 15 Chapter Two Book Readers’ particularities and Kürk Mantolu Madonna’s characteristics 30 Chapter Three Contextualising Popular Views and Romantic Realism 47 Conclusion 66 Bibliography 70 1 Introduction “Madonna in a Fur Coat makes a glorious comeback.”1 “Sabahattin Ali’s Madonna in a Fur Coat – the surprise Turkish bestseller”2 “The mysterious woman who inspired a bestselling novel”3 These are some of the several newspapers and magazines’ headlines appearing in mid 2016 when the English translated version - Madonna in a Fur Coat - of the Turkish novel Kürk Mantolu Madonna was released. These articles introduce the decades-old Turkish novel which has gained an unprecedented degree of popularity, rather surprisingly, in the past decade in Turkey. Kürk Mantolu Madonna is a story written in Turkish language by Sabahattin Ali, a Turkish journalist, poet and writer who is remembered for his Leftist political stance and articulated criticism towards the Turkish Republic’s Kemalist one-party state of the 1930s and 1940s. Born in 1907 in the Ottoman sancak (district) of Gümülcine (modern-day Greek city of Komitini) in the eastern part of the Ottoman eyalet (province) of Rumelia, Sabahattin Ali was a citizen of the Ottoman Empire and then the newly established Turkish Republic. Therefore, he witnessed his native empire’s transforming into a nation-state. Apart from that, Ali experienced the development in Europe leading up to World War II while studying in Potsdam, Germany from 1928 to 1930. -

1 Beyond Secularism: Orhan Pamuk's Snow and the Contestation Of

Konturen 1 (2008) 1 Beyond Secularism: Orhan Pamuk’s Snow and the Contestation of ‘Turkish Identity’ in the Borderland Ülker Gökberk Reed College This paper explores the multifaceted discourse on Islam in present-day Turkish society, as reflected upon in Orhan Pamuk’s 2002 novel Snow. The revival of Islam in Turkish politics and its manifestation as a lifestyle that increasingly permeates urban environments, thus challenging the secular establishment, has occasioned a crisis of ‘Turkish identity’. At the core of this vehemently contested issue stands women’s veiling, represented by its more moderate version of the headscarf. The headscarf has not only become a cultural marker of the new Islamist trend, it has also altered the meanings previously attached to socio-cultural signifiers. Thus, the old binaries of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity,’ ‘backwardness’ and ‘progress,’ applied to Islamic versus Western modes of living and employed primarily by the secularist elites and by theorists of modernization, prove insufficient to explain the novel phenomenon of Islamist identity politics. New directions in social and cultural theory on Turkey have launched a critique of modernization theory and its vocabulary based on binary oppositions. I argue that Pamuk participates, albeit from the angle of poetic imagination, in such a critique. In Snow the author explores the complexities pertaining to the cultural symbolism circulating in Turkey. The ambiguity surrounding the headscarf as a new cultural marker constitutes a major theme in the novel. I demonstrate that Snow employs multiple perspectives pertaining to the meaning of cultural symbols, thus complicating any easy assessment of the rise of Islam in Turkey. -

Sabahattin Ali

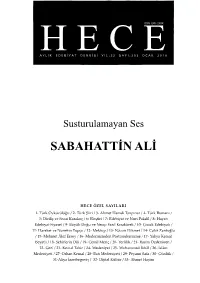

AYLIK EDEBİYAT DERGİSİ YIL:22 SAYI:253 OCAK 2018 Susturulamayan Ses SABAHATTİN ALİ HECE ÖZEL SAYILARI 1- Turk Öykuculuğu / 2- Turk Şiiri / 3- Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar / 4- Turk Romanı / 5- Diriliş ve Sezai Karakoç / 6- Eleştiri / 7- Edebiyat ve Nuri Pakdil / 8- Hayat- Edebiyat-Siyaset / 9- Buyuk Doğu ve Necip Fazıl Kısakurek / 10- Çocuk Edebiyatı / 11- Hareket ve Nurettin Topçu / 12- Mektup / 13- Nâzım Hikmet / 14- Cahit Zarifoğlu / 15- Mehmet Âkif Ersoy / 16- Modernizmden Postmodernizme / 17- Yahya Kemal Beyatlı / 18- Şehirlerin Dili / 19- Cemil Meriç / 20- Yerlilik / 21- Rasim Özdenören / 22- Gezi / 23- Kemal Tahir / 24- Medeniyet / 25- Muhammed İkbâl / 26- İslâm Medeniyeti / 27- Orhan Kemal / 28- Batı Medeniyeti / 29- Peyami Safa / 30- Gunluk / 31-Aliya İzzetbegoviç / 32- Dijital Kultur / 33- Ahmet Haşim HE CE AY LIK EDE BİYAT DER GİSİ ISSN 1301-210X YIL: 22 SA YI: 253 Ocak 2018 (Her ayın bi rin de ya yım la nır.) Ya yın Tü rü: Ye rel Sü re li He ce Ya yın cı lık Ltd.Şti. Adı na Sa hi bi ve Yazı İşleri Müdürü: Ö. Fa ruk Er ge zen Genel Yayın Yönetmeni Rasim Özdenören Yayın Kurulu Âtıf Bedir, Cafer Haydar, Hayriye Ünal, İbrahim Demirci, Yusuf Turan Günaydın Özel Sayı Editörleri Ramazan Korkmaz-İbrahim Tüzer Yö ne tim Ye ri Ko nur Sk. No: 39/1 Kı zı lay/An ka ra İletişim Tel: (312) 419 69 13 Fax: (312) 419 69 14 P.K. 79 Ye ni şe hir/An ka ra İn ter net Ad re si: www.he ce .com.tr e-ma il: he ce@he ce.com.tr twitter.com/hecedergi facebook.com/hecedergisi Tek nik Ha zır lık: Mustafa Kemiksiz Ka pak: Sa ra kus ta (www.sa ra kus ta.com.tr) Bas kı: Dumat Ofset (www.dumat.com.tr) 2018 Yı lı Abo ne Be de li: Yıl lık: 180 TL. -

Assoc. Prof. MEHMET GÜNEŞ

Assoc. Prof. MEHMET GÜNEŞ Personal Information WEmeabi:l :h mttpgsu:n//[email protected]/mgunes EDodcutocraatteio, Mna Irnmfaorar mUnaivteiorsnity, Institute of Turkic Studies, Yeni Türk Edebiyatı (Yl) (Tezli), Turkey 2004 - 2009 UPonsdtegrrgardaudautaet, eM, Oarnmdoarkau zU Mniavyeırss iÜtyn,i vInesrtsiittuetsei , oFfe Tnu-Erkdiecb Siytuadt iFeask, Yüeltneis iT, üTrükr kE dDeilbi iVyaet Eı (dYelb)i y(Tateız Bliö),l üTmurük, eTyu 2rk0e0y2 1- 929060 4- 2000 FEnogrliesihg, nB2 L Uapnpgeru Iangteersmediate Dissertations TDüorcktoiyraatt eA,r Aakştaı rGmüanldarüız E'ünns tRitoümsüa, nY, eHniik Taüyerk v Ee dTeiybaiytraotıl a(rYıln)d (aT eSzolsi)y,a 2l 0M0e9seleler (1909-1958), Marmara Üniversitesi, APorasştgtırramdaulaatreı , EHnasytiattü Msüe, cYmenuia Tsıünrdka E Eddeebbiyi aMtıu (hYtel)v (aT (eŞziliir) ,v 2e0 H0i4kaye, 1926-1929), Marmara Üniversitesi, Türkiyat RMeodseranr Tcuhr kAisrhe Laisterature Ascsaodcieatme Picro Tfeistsloers, M/ aTrmasakras University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Turkish Language and Literature, 2013 - ACossnitsitnaunet sProfessor, Marmara University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Turkish Language and Literature, 2012 - 2013 RLecsteuarrecrh, MAsasrimstanrat, UMnairvmerasritay U, Fnaivceurltsyit oy,f FAarctus latyn do fS Aciretns caensd, T Sucrieknische sL, aTnugrukaisghe Laanndg Luiategrea atunrde L, 2it0e0ra9t u- r2e0, 122003 - 2009 Advising Theses MGüünceaşd eMle.,' yYea kBuapk ıKş,a Pdoris tKgarraadousamtea, nZo.EğRluS, ÖHZa(lSidtue dEednipt) ,A 2d0ıv1a9r,Peyami Safa Ve Tarık Buğra'nın Romanlarında Millî GüÜnNeEşŞ M M.,. ,S Paeity Faamiki SAabfa'snıyına nrıokm'ına nelsaerrınledrain adşek ,b Piyoosgtgrraafidku uantes,u Er.lAarte, şP(oSsttugdreandtu)a, t2e0, 1D9.ÇAKIR(Student), 2019 GüÜnNeEşŞ M M.,. ,T Saanitz iFmaaikt dAebvarsiı yTaünrıkk ’şıniir einsedrel ebriirn pdaer baidyioggmra foikla urnaksu bralatır f, ePlosesftegsria (d1u8a3te9, -D18.Ç8a5k)ır, (DSotuctdoernatt)e, , 2Ü0.G1Ö9KMEN(Student), G20ü1n8eş M., Aşk-ı Memnu, Dudaktan Kalbe, Ağrı Dağı Efsanesi, Şu Çılgın Türkler, Midas'ın Kulakları, IV.