Recess Appointments in the Age of Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Lawyers Obey the Law?

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 1996 Should Lawyers Obey the Law? William H. Simon Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation William H. Simon, Should Lawyers Obey the Law?, 38 WM. & MARY L. REV. 217 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/880 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHOULD LAWYERS OBEY THE LAW? WmLiAM H. SIMON" At the same time that it denies authority to nonlegal norms, the dominant view of legal ethics (the "Dominant View") insists on deference to legal ones. "Zealous advocacy" stops at the "bounds of the law."' By and large, critics of the Dominant View have not chal- lenged this categorical duty of obedience to law. They typically want to add further public-regarding duties,' but they are as insistent on this one as the Dominant View. Now the idea that lawyers should obey the law seems so obvi- ous that it is rarely examined within the profession. In fact, however, once you start to think about it, the argument for a categorical duty of legal obedience encounters difficulties, and these difficulties have revealing implications for legal ethics generally. The basic difficulty is that the plausibility of a duty of obedi- ence to law depends on how we define law. -

Publicaonp ' ;INSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C

4 4 DOCOMENTAESOME. ED 210 372 UD 021 863 TITLE Th4 54ual4Rights Amendment: Guaranteeing Equa°1 Rights for Wompn Under t 'he Constitution. ClearigTjhouse PublicaonP ' ;INSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C.. *- PUB DATE Jun 81 NOTE 32p.; Not available in papei copy due tc reproduction ,quality of original document. EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS- . DESCRIPTORS , *Civil Rights Legislation: *Constitutional_ Law; Equal Educatioh; Equal Opportunities (Jobs); *Equal Protection: Federal State Relationship; Females; *Laws; *Sex fairness IDENTIFIERS *Equal Rights Amendment ,ABSTRACT This repOrt examines the effects that the ratification of thy Equal Rights Amendment will have on laws concerning women. Tfie amendment's impacts on divorced, married, and emtioTed women, on women in the military and in school, and on women 'dependent on pensions, insurance, and social securiy/ete all analyzed. A discussion of the 'Constitutional rhmificaticns of the Amerdment on the Stakes and"courts is also included. (APM) 1 .4 I. a *******i*****i****************************************************** .4 * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are they best that can be made "lc * . from'the original decument. e * 6 1 *******************************************f**************************0 7, 4 k The Equal .Rights Amendment: r4 r/ .G usranteeirig Equal Rights for yVonlyen Uncle! The Constitution LLI United States, Commission on Civil Rights Clearinghouse Puttation 68 June 1981 A X I ti "" p 4 O U.S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IERICI /Thisdocument has been reproduced as received from the person or orgerozahon ongtnahng a Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quaint Points of Anew or opinions stated as this docu 'bent do not r.tec4tsarity represent official NIE position or policy For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, 1.7.8, Oovemm °Mee, Washington, D.C. -

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

Congressional Oversight Manual

Congressional Oversight Manual Frederick M. Kaiser Specialist in American National Government Walter J. Oleszek Senior Specialist in American National Government Todd B. Tatelman Legislative Attorney June 10, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30240 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Congressional Oversight Manual Summary The Congressional Research Service (CRS) developed the Congressional Oversight Manual over 30 years ago, following a three-day December 1978 Workshop on Congressional Oversight and Investigations. The workshop was organized by a group of House and Senate committee aides from both parties and CRS at the request of the bipartisan House leadership. The Manual was produced by CRS with the assistance of a number of House committee staffers. In subsequent years, CRS has sponsored and conducted various oversight seminars for House and Senate staff and updated the Manual as circumstances warranted. The last revision occurred in 2007. Worth noting is the bipartisan recommendation of the House members of the 1993 Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress (Rept. No. 103-413, Vol. I): [A]s a way to further enhance the oversight work of Congress, the Joint Committee would encourage the Congressional Research Service to conduct on a regular basis, as it has done in the past, oversight seminars for Members and congressional staff and to update on a regular basis its Congressional Oversight Manual. Over the years, CRS has assisted many members, committees, party leaders, and staff aides in the performance of the oversight function, that is, the review, monitoring, and supervision of the implementation of public policy. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

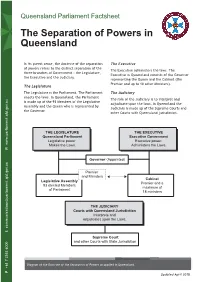

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

Congress's Contempt Power: Law, History, Practice, and Procedure

Congress’s Contempt Power and the Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas: Law, History, Practice, and Procedure Todd Garvey Legislative Attorney May 12, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34097 Congress’s Contempt Power and the Enforcement of Congressional Subpoenas Summary Congress’s contempt power is the means by which Congress responds to certain acts that in its view obstruct the legislative process. Contempt may be used either to coerce compliance, to punish the contemnor, and/or to remove the obstruction. Although arguably any action that directly obstructs the effort of Congress to exercise its constitutional powers may constitute a contempt, in recent times the contempt power has most often been employed in response to non- compliance with a duly issued congressional subpoena—whether in the form of a refusal to appear before a committee for purposes of providing testimony, or a refusal to produce requested documents. Congress has three formal methods by which it can combat non-compliance with a duly issued subpoena. Each of these methods invokes the authority of a separate branch of government. First, the long dormant inherent contempt power permits Congress to rely on its own constitutional authority to detain and imprison a contemnor until the individual complies with congressional demands. Second, the criminal contempt statute permits Congress to certify a contempt citation to the executive branch for the criminal prosecution of the contemnor. Finally, Congress may rely on the judicial branch to enforce a congressional subpoena. Under this procedure, Congress may seek a civil judgment from a federal court declaring that the individual in question is legally obligated to comply with the congressional subpoena. -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges. -

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body Karen Arland Ice Miller LLP September 27, 2017 Ice on Fire Separation of Powers Division of governmental authority into three branches – legislative, executive and judicial, each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach A constitutional doctrine of checks and balances designed to protect the people against tyranny 1 Ice on Fire Historical Background The phrase “separation of powers” is traditionally ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Also known as “Montesquieu’s tri-partite system,” the theory was the division of political power between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary as the best method to promote liberty. 2 Ice on Fire Constitution of the United States Article I – Legislative Section 1 – All legislative Powers granted herein shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. Article II – Executive Section 1 – The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. Article III – Judicial The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. 3 Ice on Fire Indiana Constitution of 1816 Article II - The powers of the Government of Indiana shall be divided into three distinct departments, and each of them be confided to a separate body of Magistracy, to wit: those which are Legislative to one, those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judiciary to another: And no person or collection of persons, being of one of those departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted. -

3. the Powers and Tools Available to Congress for Conducting Investigative Oversight A

H H H H H H H H H H H 3. The Powers and Tools Available to Congress for Conducting Investigative Oversight A. Congress’s Power to Investigate 1. The Breadth of the Investigatory Power Congress possesses broad and encompassing powers to engage in oversight and conduct investigations reaching all sources of information necessary to carry out its legislative functions. In the absence of a countervailing constitutional privilege or a self-imposed restriction upon its authority, Congress and its committees have virtually plenary power to compel production of information needed to discharge their legislative functions. This applies whether the information is sought from executive agencies, private persons, or organizations. Within certain constraints, the information so obtained may be made public. These powers have been recognized in numerous Supreme Court cases, and the broad legislative authority to seek information and enforce demands was unequivocally established in two Supreme Court rulings arising out of the 1920s Teapot Dome scandal. In McGrain v. Daugherty,1 which considered a Senate investigation of the Justice Department, the Supreme Court described the power of inquiry, with accompanying process to enforce it, as “an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function.” The court explained: A legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change; and where the legislative body does not possess the requisite -

Appointment and Confirmation of Executive

Appointment and Confirmation of Executive Branch Leadership: An Overview name redacted Specialist in American National Government name redacted Analyst in Government Organization and Management June 22, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44083 Appointment and Confirmation of Executive Branch Leadership: An Overview Summary The Constitution divides the responsibility for populating the top positions in the executive branch of the federal government between the President and the Senate. Article II, Section 2 empowers the President to nominate and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to appoint the principal officers of the United States, as well as some subordinate officers. These positions are generally filled through the advice and consent process, which can be divided into three stages: • First, the White House selects and clears a prospective appointee before sending a formal nomination to the Senate. • Second, the Senate determines whether to confirm a nomination. For most nominations, much of this process occurs at the committee level. • Third, the confirmed nominee is given a commission and sworn into office, after which he or she has full authority to carry out the duties of the office. The President may also be able to fill vacancies in advice and consent positions in the executive branch temporarily through other means. If circumstances permit and conditions are met, the President could choose to give a recess appointment to an individual. Such an appointment would last until the end of the next session of the Senate. Alternatively, in some cases, the President may be able to designate an official to serve in a vacant position on a temporary basis under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act or under statutory authority specific to the position. -

The Separation of Powers Doctrine: an Overview of Its Rationale and Application

Order Code RL30249 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application June 23, 1999 (name redacted) Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress ABSTRACT This report discusses the philosophical underpinnings, constitutional provisions, and judicial application of the separation of powers doctrine. In the United States, the doctrine has evolved to entail the identification and division of three distinct governmental functions, which are to be exercised by separate branches of government, classified as legislative, executive, and judicial. The goal of this separation is to promote governmental efficiency and prevent the excessive accumulation of power by any single branch. This has been accomplished through a hybrid doctrine comprised of the separation of powers principle and the notion of checks and balances. This structure results in a governmental system which is independent in certain respects and interdependent in others. The Separation of Powers Doctrine: An Overview of its Rationale and Application Summary As delineated in the Constitution, the separation of powers doctrine represents the belief that government consists of three basic and distinct functions, each of which must be exercised by a different branch of government, so as to avoid the arbitrary exercise of power by any single ruling body. This concept was directly espoused in the writings of Montesquieu, who declared that “when the executive