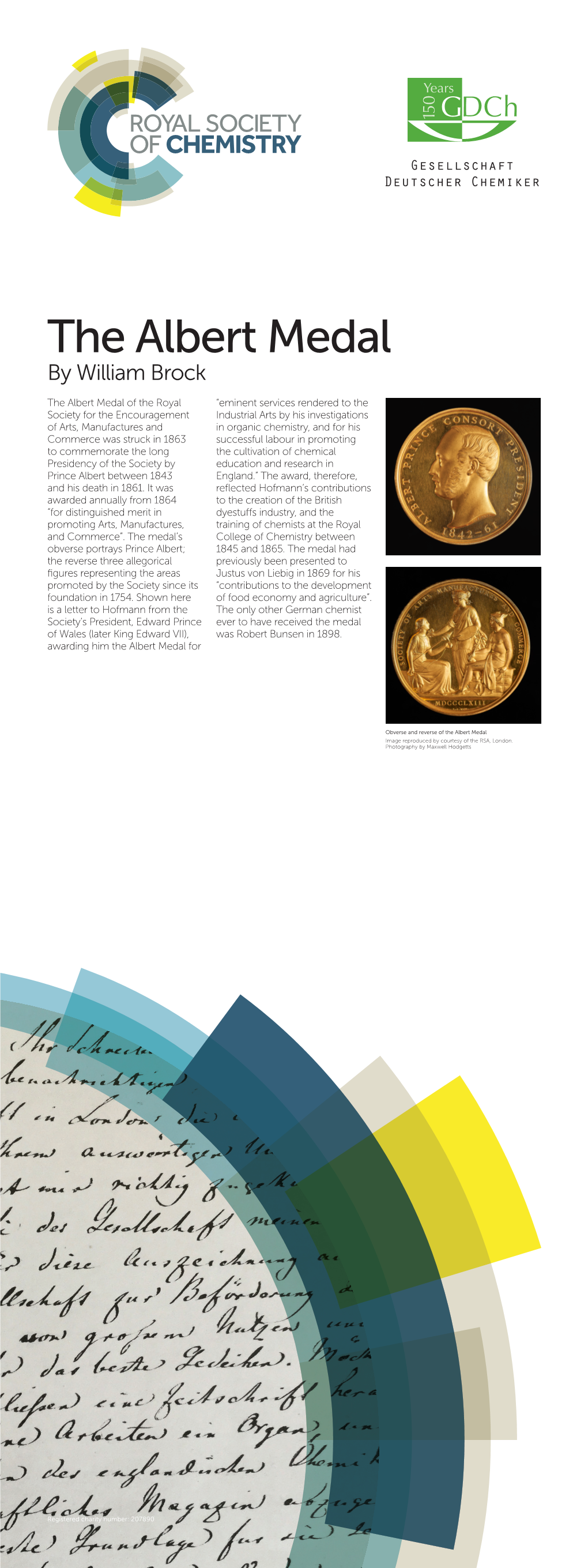

The Albert Medal by William Brock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sturm Und Dung: Justus Von Liebig and the Chemistry of Agriculture

Sturm und Dung: Justus von Liebig and the Chemistry of Agriculture Pat Munday, Montana Tech, Butte, Montana 59701-8997, USA In August of 1990, I completed a PhD dissertadon titled "Sturm und Dung: Justus von Liebig and the Chemistry of Agriculture"1 as a graduate Student with the Program in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology at Comell University. In this work, I tried to utilize the historical tools I had lear- ned from the members my doctoral committee, Chaired by Professor Dr. L. Pearce Williams; the other two members of my committee were Professor Dr. Isabel V. Hüll and Professor Dr. Margaret W. Rossiter. Briefly, these tools included: a thorough mastery of the secondary literature; utilizadon of primary and manuscript sources, especially manuscript sources neglected by previous historians; and "a radical cridque of central institudons and sacred cows" achieved, in part, through "focussing on eccentricity and contradiction. "2 As mentors for my life and models3 for my work, I thank Professors Williams, Hüll, and Rossiter, and apologize for my shortcomings as their Student. I have published a few articles cannibalized from my dissertadon.4 Since I now am fortunate enough to work with an insdtudon that emphasizes teaching over the publication of obscure books, I have never been pressured to publish my dissertadon as such. Based on my correspondence and rare attendance at Pro- fessional meetings, I thought my work on Liebig had been received lukewannly at best. It therefore came as a great surprise when, because of my dissertadon, I received one of the two 1994 Liebig-Wöhler-Freundschafts Preise sponsored by Wilhelm Lewicki and awarded by the Göttinger Chemische Gesellschaft. -

Biography: Justus Von Liebig

Biography: Justus von Liebig Justus von Liebig (1803 – 1873) was a German chemist. He taught chemistry at the University of Giessen and the University of Munich. The University of Giessen currently bears his name. Liebig is called the father of fertilizers. He confirmed the hypothesis concerning the mineral nutrition of plants, which became the basis for the development of modern agricultural chemistry. Liebig’s research is considered a precursor to the study of the impact of environmental factors on organisms. He formulated the law of the minimum, which states that the scarcest resource is what limits a given organism. He also developed a process for producing meat extract and founded the company Liebig Extract of Meat Company whose trademark was the beef bouillon cube, which he invented. Justus von Liebig was born into a middle class In 1824, at the age of 21, Liebig became a family from Darmstadt on May 12, 1803. As a professor at the University of Giessen. While in child, he was already fascinated by chemistry. Germany, he founded and edited the magazine When he was 13 years old, most of the crops in the Annalen der Chemie, which became the leading Northern Hemisphere were destroyed by a journal of chemistry in Germany. volcanic winter. Germans were among the most In 1837, he was elected a member of the Royal affected. It is said that this experience influenced Swedish Academy of Sciences, and in 1845, started the subsequent work of Liebig and the working at the University of Munich, where he establishment of his company. remained until his death. -

Monday Morning Plenary

By Kelpie Wilson Biochar in the 19th Century The role of agricultural chemist Justus Liebig 19th century “bloggers” spread the charcoal meme Charcoal in a campaign to save the starving Irish Charcoal and the London Sewage Question Charcoal and food security Some Final Questions Justus von Liebig 1803 - 1873 Justus Liebig is recognized as one of the first genuine experimental chemists. At a young age, he established a laboratory at Giessen that was the envy of Europe. Beginnings of Chemical Agriculture Through his experimental work, Liebig established the "law of the minimum," that states that plant growth is constrained by the least available nutrient in the soil. These discoveries spurred a growing fertilizer industry that mined and shipped huge amounts of guano, bonemeal, lime and other fertilizers from all parts of the world to fertilize the fields of Europe and eliminate the need for crop rotations and fallow periods to replenish the soil. Vitalism or Physical Determinism? In Liebig’s time, the chemical approach to agriculture was new. The prevailing theories invoked the principle of vitalism. Vitalism: A doctrine that the functions of a living organism are due to a vital principle distinct from physicochemical forces. Believers in vitalism thought that black soil contained an organic life force or "vitalism" that could not be derived from dead, inorganic chemicals. This theory was based on the well-known fact that "virgin" soil from recently cleared forests was black and fertile. Early chemists extracted this black substance and called it “humus”. Was vitalism a relic of ancient religion? The Greek Goddess Gaia – Goddess of the Fertile Earth Black Virgin images found in churches throughout Europe may represent the vital principle of the black soil. -

History Group Newsletter

HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER News, views and a miscellany published by the Royal Meteorological Society’s Special Interest Group for the History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Issue No.2, 2015 CONTENTS VALETE AND THANK YOU Valete and thank you .................................. 1 In this issue ................................................. 1 from Malcolm Walker Forthcoming meetings ................................ 2 All members of the History Group should know The year without a summer, 1816 ............... 3 by now that I have stepped down as Chairman After the death of Admiral FitzRoy .............. 3 of the Group. I had planned to do this in 2016, Jehuda Neumann Memorial Prize ............... 11 by which time I would have chaired the Group Did you know? ............................................ 11 for nineteen years. My hand has been forced, Forgotten met offices – Butler’s Cross ......... 12 however, by the onset of cancer. Mountaintop weather ................................. 15 Mountaintop weather continued ................ 16 The Group was founded towards the end of Operational centenary ................................ 17 1982 and held its first meetings in 1983. I have Units and Daylight Saving Time ................... 20 been a member of the Group’s committee The Royal Meteorological Society in 1904 ... 22 from the outset. Publications by History Group members ..... 23 I have received a very large number of letters, The troubled story of the Subtropical Jet .... 24 cards and emails expressing best wishes and The Met Éireann Library .............................. 29 goodwill for a speedy and full recovery from Recent publications .................................... 30 Different views of the Tower of the Winds .. 31 my illness. I am so very grateful for the many National Meteorological Library and Archive 31 kind words you have written, especially for the 2015 members ........................................... -

"Early Roots of the Organic Movement: a Plant Nutrition Perspective"

and beast. But that which came from earth there is nothing more beneficial than to turn up a Early Roots of the must return to earth and that which came crop of lupines, before they have podded, eitherwith Organic Movement: from air to air. Death, however, does not the plough or the fork, or else to cut them and bury destroy matter but only breaks up the union them them in heaps at the roots of trees and vines.” A Plant Nutrition of its elements which are then recombined Though Pliny and subsequent writers over into other forms. (Browne, 1943) the centuries extolled the benefits of manuring Perspective from a scientific viewpoint, little advance was This atomic, cyclic, and nonconvertible chain made on the reasons for these benefits. Generally, ofelements through thesoil-plant-animal system the Aristotelian concept of the four elements held Ronald F. Korcak was opposed by Aristotle’s (384-322 BC) mutual sway into the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages, convertibility of the four elements: earth, water, generally, represent a quiescent period devoid of fire, and air. Since, according to Aristotle, the any advances in scienceand technology-no less material constituents of the world were formed in the understanding of plant mineral nutrition. from unions of these four elements, plants assimi- Some notable exceptions to this void would have Additional index words. humus theory, lated minute organic matter particles through their profound influences on the development of a theory Justus von Liebig, plant nutrition roots which were preformed miniatures (Browne, of plant nutrition near the end of the Middle Ages. -

Before Radicals Were Free – the Radical Particulier of De Morveau

Review Before Radicals Were Free – the Radical Particulier of de Morveau Edwin C. Constable * and Catherine E. Housecroft Department of Chemistry, University of Basel, BPR 1096, Mattenstrasse 24a, CH-4058 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-207-1001 Received: 31 March 2020; Accepted: 17 April 2020; Published: 20 April 2020 Abstract: Today, we universally understand radicals to be chemical species with an unpaired electron. It was not always so, and this article traces the evolution of the term radical and in this journey, monitors the development of some of the great theories of organic chemistry. Keywords: radicals; history of chemistry; theory of types; valence; free radicals 1. Introduction The understanding of chemistry is characterized by a precision in language such that a single word or phrase can evoke an entire back-story of understanding and comprehension. When we use the term “transition element”, the listener is drawn into an entire world of memes [1] ranging from the periodic table, colour, synthesis, spectroscopy and magnetism to theory and computational chemistry. Key to this subliminal linking of the word or phrase to the broader context is a defined precision of terminology and a commonality of meaning. This is particularly important in science and chemistry, where the precision of meaning is usually prescribed (or, maybe, proscribed) by international bodies such as the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry [2]. Nevertheless, words and concepts can change with time and to understand the language of our discipline is to learn more about the discipline itself. The etymology of chemistry is a complex and rewarding subject which is discussed eloquently and in detail elsewhere [3–5]. -

Justus Liebig Life and Work

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA CHIMICA 13,2004 JUSTUS LIEBIG LIFE AND WORK by Helmut Gebelein Justus Liebig University, Department of Chemical Didactics, Heinrich Buff-Ring 58, 35392 Giessen, Germany Fig. 1. Freiherr Justus von Liebig, 1864 Liebig was not only one of the most prominent chemists of the 19th century, he had also done important work in agriculture and in nutrition. He even wrote articles about philosophical problems, he improved a special method of fresco painting, and with his Chemical Letters he produced one of the best books on chemistry for the laymen. A similar work on modern chemistry is still lacking. Liebig was born on the 12th of May 1803, in Darmstadt, a town some 20 kilometres to the south of Frankfurt. At this time Darmstadt was the capital of Hessen-Darmstadt, one of the small German states. Duke Ludwig 1 of Hessen-Darmstadt was interested in the advancement of the sciences. He even had a university at Giessen, founded in 1607. This university is today called Justus Liebig-University after its most prominent scientific scholar. Liebig’s father had a drysalt and hardware shop and he owned a small laboratory where he produced drugs and materials, e.g. pigments for colours. Through the father’s laboratory Justus became interested in chemical processes already in his youth and he wanted to become a chemist. He read all the books on chemistry he could get hold of. The court library where he borrowed most of these books was unfortunately not very up to date. He could not learn modern chemistry in this way. -

Justus Liebig, Organic Analysis, and Chemical Pedagogy

Justus Liebig, Organic Analysis, and Chemical Pedagogy Monday, October 4, 2010 Transformation of Organic Chemistry, 1820-1850 • Enormous increase in the number of “organic” compounds • ~100 in 1820, thousands by 1860. • doubling approximately every nine years • The majority of these compounds are artificial. • Change in meaning of “organic” • Relative unimportant branch of chemistry to the largest and most important branch of chemistry • Natural history to experimental science • Chemistry as Wissenschaft, not an ancillary to medicine • Professionalization of chemists Monday, October 4, 2010 Transformation of Organic Chemistry, 1820-1850 Reasons for this transformation: • Recognition of isomerism. • Explanation of isomerism by “arrangement.” • The rapid adoption of Berzelian notation as “paper tools” • Justus Liebig’s invention of the Kaliapparat for organic analysis Monday, October 4, 2010 Combustion Analysis of Organic Compounds CxHyOz+ oxygen ––> carbonic acid gas + water • carbonic acid gas = carbon content • water = hydrogen content • oxygen calculated by difference • nitrogen determined by a separate combustion analysis: CxHyOzNa+ oxygen ––> carbonic acid gas + nitrogen + water Monday, October 4, 2010 Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778-1850) Louis Jacques Thénard (1777-1857) Monday, October 4, 2010 Monday, October 4, 2010 Jöns Jakob Berzelius (1779-1848) Monday, October 4, 2010 Monday, October 4, 2010 Justus von Liebig (1800-1873) Monday, October 4, 2010 Monday, October 4, 2010 Justus von Liebig • Born 1803 in Darmstadt • 1821: University of Erlangen, influenced by Karl Wilhelm Gottlob Kastner • Intending a teaching career • October 1822-March 1824: Paris • Worked closely with Gay-Lussac on the composition of fulminates • Decides that he is capable of Wissenschaft, not just teaching • April 1824: Außerordentlicher Professor at University of Gießen. -

Pride and Prejudice in Chemistry

Bull. Hist. Chem. 13 - 14 (1992-93) 29 reactions involving oxygen - perhaps a faint resonance of the voisier?) of the fact that the weight of the chemical reagents historical association of that principle with Lavoisier. before and after a reaction must be unchanged, but rather the Such silence is perhaps doubly surprising since not only had explicit enunciation of a particular principle and the kinds of Lavoisier enunciated the principle of the conservation of assumptions which finally made that enunciation reasonable in matter in 1789, but in Germany Immanuel Kant had laid down ways it hadn't been before. The parallel and explicit formula- a similar principle in his influential Metaphysical Foundations tion of both conservation principles as fundamental principles f Natural Science of 1786. For Kant, the first principle of of the sciences of chemistry and physics was in the first mechanics was that "in all changes in the corporeal world the instance the work of Robert Mayer. Lavoisier notwithstand- quantity of matter remains on the whole the same, unincreased ing, it appears to me that, for the larger scientific community, and undiminished." Yet Kant also assigned to matter primitive the general recognition of the principle of the conservation of attractive and repulsive forces, and the "dynamical" philoso- matter went hand in hand with, and was only made possible by phies of nature which were popular in early 19th-century the general acceptance of the principle of the conservation of Germany tended to eliminate matter entirely in favor of its energy during the second half of the 19th century. -

Bernhard Riemann on the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Bases

Classic Texts in the Sciences Jürgen Jost Editor Bernhard Riemann On the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Bases of Geometry Bernhard Riemann On the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Bases of Geometry Classic Texts in the Sciences Series Editors Olaf Breidbach () Jürgen Jost Classic Texts in the Sciences offers essential readings for anyone interested in the origin and roots of our present-day culture. Considering the fact that the sciences have significantly shaped our contemporary world view, this series not only provides the original texts but also extensive historical as well as scientific commentary, linking the classic texts to current developments. Classic Texts in the Sciences presents classic texts and their authors not only for specialists but for anyone interested in the background and the various facets of our civilization. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11828 Jürgen Jost Editor Bernhard Riemann On the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Bases of Geometry Editor JurgenR Jost Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences Leipzig, Germany ISSN 2365-9963 ISSN 2365-9971 (electronic) Classic Texts in the Sciences ISBN 978-3-319-26040-2 ISBN 978-3-319-26042-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-26042-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016936876 Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 51-03, 53-03, 53B20, 53Z05, 00A30, 01A55, 83-03 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

A Distinctly Human Quest

ehind t b h y e r s c o c A DistinctlyDistinctly HumanHuman QuestQuest t t i i e e s s n n e e c c The Demise of Vitalism and the h h e e T T Search for Life’s Origins Stanley Miller “Beilstein,” said Harold Urey, describing his thoughts in Harvey asked questions and conducted studies that 1953 on his graduate student Stanley Miller's ongoing overthrew Galen's ideas and resulted in the now accepted experiment to synthesize amino acids from inorganic idea that blood circulates through the body. However, matter. He meant that the experiment would revolutionize while he provided a mechanical view of blood circulation, chemistry and produce more work than Friedrich he maintained that blood was a spiritual fluid. This is Beilstein's 100-volume Handbuch der Organische understandable given that he was unable to provide a Chemie. But as quickly as chemists and biologists hailed mechanical explanation for body heat or energy. Vitalism Miller for determining a possible mechanism for the persisted into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. formation of life on Earth, they turned on his idea as Those accepting some sort of vitalistic position included incomplete. Miller's experiment demonstrated how amino most of the well known figures in the history of the life acids and other organic compounds could be formed on a sciences. At this time vitalism, the view that living prehistoric Earth with an atmosphere featuring the right processes could not all be explained by chemistry and combination of chemicals. But it almost never happened. -

Beginnings of Microbiology and Biochemistry: the Contribution of Yeast Research

Microbiology (2003), 149, 557–567 DOI 10.1099/mic.0.26089-0 Review Beginnings of microbiology and biochemistry: the contribution of yeast research James A. Barnett Correspondence School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK [email protected] With improvements in microscopes early in the nineteenth century, yeasts were seen to be living organisms, although some famous scientists ridiculed the idea and their influence held back the development of microbiology. In the 1850s and 1860s, yeasts were established as microbes and responsible for alcoholic fermentation, and this led to the study of the roˆ le of bacteria in lactic and other fermentations, as well as bacterial pathogenicity. At this time, there were difficulties in distinguishing between the activities of microbes and of extracellular enzymes. Between 1884 and 1894, Emil Fischer’s study of sugar utilization by yeasts generated an understanding of enzymic specificity and the nature of enzyme–substrate complexes. Overview microbiological occurrence. And, as for many years there had been a widely accepted analogy between fermentation and Early in the nineteenth century, even the existence of living disease, the germ theory of fermentation implied a germ microbes was a matter of debate. This article describes how theory of disease. There were, however, passionate con- biologists, studying yeasts as the cause of fermentation, troversies arising from the difficulty of distinguishing came to recognize the reality of micro-organisms and began between microbial action and enzymic action and towards to characterize them. However, it was not until the last the end of the nineteenth century, work on yeast sugar quarter of the nineteenth century that people knew with any fermentations gave convincing evidence of the specificity of certainty that microbes are important causes of diseases.