OFAC Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ransom Where?

Ransom where? Holding data hostage with ransomware May 2019 Author With the evolution of digitization and increased interconnectivity, the cyberthreat landscape has transformed from merely a security and privacy concern to a danger much more insidious by nature — ransomware. Ransomware is a type of malware that is designed to encrypt, Imani Barnes Analyst 646.572.3930 destroy or shut down networks in exchange [email protected] for a paid ransom. Through the deployment of ransomware, cybercriminals are no longer just seeking to steal credit card information and other sensitive personally identifiable information (PII). Instead, they have upped their games to manipulate organizations into paying large sums of money in exchange for the safe release of their data and control of their systems. While there are some business sectors in which the presence of this cyberexposure is overt, cybercriminals are broadening their scopes of potential victims to include targets of opportunity1 across a multitude of industries. This paper will provide insight into how ransomware evolved as a cyberextortion instrument, identify notorious strains and explain how companies can protect themselves. 1 WIRED. “Meet LockerGoga, the Ransomware Crippling Industrial Firms” March 25, 2019; https://www.wired.com/story/lockergoga-ransomware-crippling-industrial-firms/. 2 Ransom where? | May 2019 A brief history of ransomware The first signs of ransomware appeared in 1989 in the healthcare industry. An attacker used infected floppy disks to encrypt computer files, claiming that the user was in “breach of a licensing agreement,”2 and demanded $189 for a decryption key. While the attempt to extort was unsuccessful, this attack became commonly known as PC Cyborg and set the archetype in motion for future attacks. -

Advanced Persistent Threats

THREAT RESEARCH Defending Against Advanced Persistent Threats Introduction As the name “Advanced” suggests, APT (advanced persistent threat) is one of the most sophisticated and organized forms of network attacks that keep cybersecurity professionals up at night. Unlike many hit & run traditional cyberattacks, an APT is carried out over a prolonged period of time by skilled threat actors who strategize multi-staged campaigns against their targets, employing clandestine tools & techniques such as Remote Administration Tools (RAT), Toolkits, Backdoor Trojans, Social Engineering, DNS Tunneling etc. These experienced cybercriminals are mostly backed & well-funded by nation states and corporation-backed organizations to specifi cally target high value organizations with the following objectives in mind: a Theft of Intellectual Property & classifi ed data i.e. Cyber Espionage a Access to critical & sensitive communications a Access to credentials of critical systems a Sabotage or exfi ltration of databases a Theft of Personal Identifi able Information (PII) a Access to critical infrastructure to perform internal reconnaissance To achieve the above goals, APT Groups use novel techniques to obfuscate their actions and easily bypass traditional security barriers that are not advancing at the same rate as the sophisticated attack patterns of cybercriminals. To understand the evolved behavioral pattern of APT Groups in the year 2020, a review of their latest activities revealed interesting developments and a few groundbreaking events¹: a Southeast Asia -

Post-Mortem of a Zombie: Conficker Cleanup After Six Years Hadi Asghari, Michael Ciere, and Michel J.G

Post-Mortem of a Zombie: Conficker Cleanup After Six Years Hadi Asghari, Michael Ciere, and Michel J.G. van Eeten, Delft University of Technology https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity15/technical-sessions/presentation/asghari This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 24th USENIX Security Symposium August 12–14, 2015 • Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-1-939133-11-3 Open access to the Proceedings of the 24th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Post-Mortem of a Zombie: Conficker Cleanup After Six Years Hadi Asghari, Michael Ciere and Michel J.G. van Eeten Delft University of Technology Abstract more sophisticated C&C mechanisms that are increas- ingly resilient against takeover attempts [30]. Research on botnet mitigation has focused predomi- In pale contrast to this wealth of work stands the lim- nantly on methods to technically disrupt the command- ited research into the other side of botnet mitigation: and-control infrastructure. Much less is known about the cleanup of the infected machines of end users. Af- effectiveness of large-scale efforts to clean up infected ter a botnet is successfully sinkholed, the bots or zom- machines. We analyze longitudinal data from the sink- bies basically remain waiting for the attackers to find hole of Conficker, one the largest botnets ever seen, to as- a way to reconnect to them, update their binaries and sess the impact of what has been emerging as a best prac- move the machines out of the sinkhole. This happens tice: national anti-botnet initiatives that support large- with some regularity. The recent sinkholing attempt of scale cleanup of end user machines. -

ERP Applications Under Fire How Cyberattackers Target the Crown Jewels

ERP Applications Under Fire How cyberattackers target the crown jewels July 2018 v1.0 With hundreds of thousands of implementations across the globe, Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) applications are supporting the most critical business processes for the biggest organizations in the world. This report is the result of joint research performed by Digital Shadows and Onapsis, aimed to provide insights into how the threat landscape has been evolving over time for ERP applications. We have concentrated our efforts on the two most widely-adopted solutions across the large enterprise segment, SAP and Oracle E-Business Suite, focusing on the risks and threats organizations should care about. According to VP Distinguished Analyst, Neil MacDonald “As financially motivated attackers turn their attention ‘up the stack’ to the application layer, business applications such as ERP, CRM and human resources are attractive targets. In many organizations, the ERP application is maintained by a completely separate team and security has not been a high priority. As a result, systems are often left unpatched for years in the name of operational availability.” Gartner, Hype Cycle for Application Security, 2017, July 2017 1 1 Gartner, Hype Cycle for Application Security, 2017, Published: 28 July 2017 ID: G00314199, Analyst(s): Ayal Tirosh, https://www.gartner.com/doc/3772095/hype-cycle-application-security- 02 Executive Summary With hundreds of thousands of implementations across the globe, Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) applications support the most critical business processes and house the most sensitive information for the biggest organizations in the world. The vast majority of these large organizations have implemented ERP applications from one of the two market leaders, SAP and Oracle. -

PARK JIN HYOK, Also Known As ("Aka") "Jin Hyok Park," Aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case Fl·J 18 - 1 4 79

AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the RLED Central District of California CLERK U.S. DIS RICT United States ofAmerica JUN - 8 ?018 [ --- .. ~- ·~".... ~-~,..,. v. CENT\:y'\ l i\:,: ffl1G1 OF__ CAUFORN! BY .·-. ....-~- - ____D=E--..... PARK JIN HYOK, also known as ("aka") "Jin Hyok Park," aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case fl·J 18 - 1 4 79 Defendant. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best ofmy knowledge and belief. Beginning no later than September 2, 2014 and continuing through at least August 3, 2017, in the county ofLos Angeles in the Central District of California, the defendant violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 371 Conspiracy 18 u.s.c. § 1349 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud This criminal complaint is based on these facts: Please see attached affidavit. IBJ Continued on the attached sheet. Isl Complainant's signature Nathan P. Shields, Special Agent, FBI Printed name and title Sworn to before ~e and signed in my presence. Date: ROZELLA A OLIVER Judge's signature City and state: Los Angeles, California Hon. Rozella A. Oliver, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title -:"'~~ ,4G'L--- A-SA AUSAs: Stephanie S. Christensen, x3756; Anthony J. Lewis, x1786; & Anil J. Antony, x6579 REC: Detention Contents I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 II. PURPOSE OF AFFIDAVIT ......................................................................1 III. SUMMARY................................................................................................3 -

The Botnet Chronicles a Journey to Infamy

The Botnet Chronicles A Journey to Infamy Trend Micro, Incorporated Rik Ferguson Senior Security Advisor A Trend Micro White Paper I November 2010 The Botnet Chronicles A Journey to Infamy CONTENTS A Prelude to Evolution ....................................................................................................................4 The Botnet Saga Begins .................................................................................................................5 The Birth of Organized Crime .........................................................................................................7 The Security War Rages On ........................................................................................................... 8 Lost in the White Noise................................................................................................................. 10 Where Do We Go from Here? .......................................................................................................... 11 References ...................................................................................................................................... 12 2 WHITE PAPER I THE BOTNET CHRONICLES: A JOURNEY TO INFAMY The Botnet Chronicles A Journey to Infamy The botnet time line below shows a rundown of the botnets discussed in this white paper. Clicking each botnet’s name in blue will bring you to the page where it is described in more detail. To go back to the time line below from each page, click the ~ at the end of the section. 3 WHITE -

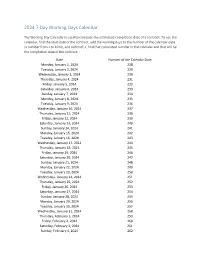

2024 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2024 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Monday, January 1, 2024 228 Tuesday, January 2, 2024 229 Wednesday, January 3, 2024 230 Thursday, January 4, 2024 231 Friday, January 5, 2024 232 Saturday, January 6, 2024 233 Sunday, January 7, 2024 234 Monday, January 8, 2024 235 Tuesday, January 9, 2024 236 Wednesday, January 10, 2024 237 Thursday, January 11, 2024 238 Friday, January 12, 2024 239 Saturday, January 13, 2024 240 Sunday, January 14, 2024 241 Monday, January 15, 2024 242 Tuesday, January 16, 2024 243 Wednesday, January 17, 2024 244 Thursday, January 18, 2024 245 Friday, January 19, 2024 246 Saturday, January 20, 2024 247 Sunday, January 21, 2024 248 Monday, January 22, 2024 249 Tuesday, January 23, 2024 250 Wednesday, January 24, 2024 251 Thursday, January 25, 2024 252 Friday, January 26, 2024 253 Saturday, January 27, 2024 254 Sunday, January 28, 2024 255 Monday, January 29, 2024 256 Tuesday, January 30, 2024 257 Wednesday, January 31, 2024 258 Thursday, February 1, 2024 259 Friday, February 2, 2024 260 Saturday, February 3, 2024 261 Sunday, February 4, 2024 262 Date Number of the Calendar Date Monday, February 5, 2024 263 Tuesday, February 6, 2024 264 Wednesday, February -

LAZARUS UNDER the HOOD Executive Summary

LAZARUS UNDER THE HOOD Executive Summary The Lazarus Group’s activity spans multiple years, going back as far as 2009. Its malware has been found in many serious cyberattacks, such as the massive data leak and file wiper attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014; the cyberespionage campaign in South Korea, dubbed Operation Troy, in 2013; and Operation DarkSeoul, which attacked South Korean media and financial companies in 2013. There have been several attempts to attribute one of the biggest cyberheists, in Bangladesh in 2016, to Lazarus Group. Researchers discovered a similarity between the backdoor used in Bangladesh and code in one of the Lazarus wiper tools. This was the first attempt to link the attack back to Lazarus. However, as new facts emerged in the media, claiming that there were at least three independent attackers in Bangladesh, any certainty about who exactly attacked the banks systems, and was behind one of the biggest ever bank heists in history, vanished. The only thing that was certain was that Lazarus malware was used in Bangladesh. However, considering that we had previously found Lazarus in dozens of different countries, including multiple infections in Bangladesh, this was not very convincing evidence and many security researchers expressed skepticism abound this attribution link. This paper is the result of forensic investigations by Kaspersky Lab at banks in two countries far apart. It reveals new modules used by Lazarus group and strongly links the tools used to attack systems supporting SWIFT to the Lazarus Group’s arsenal of lateral movement tools. Considering that Lazarus Group is still active in various cyberespionage and cybersabotage activities, we have segregated its subdivision focusing on attacks on banks and financial manipulations into a separate group which we call Bluenoroff (after one of the tools they used). -

Marked for Disruption: Tracing the Evolution of Malware Delivery Operations Targeted for Takedown

Marked for Disruption: Tracing the Evolution of Malware Delivery Operations Targeted for Takedown Colin C. Ife¢, Yun Sheny, Steven J. Murdoch¢, and Gianluca Stringhiniz ¢University College London, yNorton Research Group, zBoston University ¢yUnited Kingdom, zUnited States {colin.ife,s.murdoch}@ucl.ac.uk,[email protected],[email protected] ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION The malware and botnet phenomenon is among the most signif- Malware delivery has evolved into a major business for the cyber- icant threats to cybersecurity today. Consequently, law enforce- criminal economy and a complex problem for the security commu- ment agencies, security companies, and researchers are constantly nity. The botnet – a network of malware-infected devices that is seeking to disrupt these malicious operations through so-called controlled by a single actor through one or more command and takedown counter-operations. Unfortunately, the success of these control (C&C) servers – is one phenomenon that has benefited takedowns is mixed. Furthermore, very little is understood as to from the malware delivery revolution. Diverse distribution vectors how botnets and malware delivery operations respond to takedown have enabled such malicious networks to expand more quickly and attempts. We present a comprehensive study of three malware de- efficiently than ever before. Once established, these botnets canbe livery operations that were targeted for takedown in 2015–16 using leveraged to commit a wide array of secondary computer crimes, global download metadata provided by Symantec. In summary, we such as data theft, financial fraud, coercion (ransomware), send- found that: (1) Distributed delivery architectures were commonly ing spam messages, distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, used, indicating the need for better security hygiene and coordina- and unauthorised cryptocurrency mining [1, 14, 17, 47, 48]. -

Council Decision (Cfsp)

L 246/12 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 30.7.2020 COUNCIL DECISION (CFSP) 2020/1127 of 30 July 2020 amending Decision (CFSP) 2019/797 concerning restrictive measures against cyber-attacks threatening the Union or its Member States THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in particular Article 29 thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 17 May 2019 the Council adopted Decision (CFSP) 2019/797 (1). (2) Targeted restrictive measures against cyber-attacks with a significant effect which constitute an external threat to the Union or its Member States are among the measures included in the Union’s framework for a joint diplomatic response to malicious cyber-activities (the cyber diplomacy toolbox) and are a vital instrument to deter and respond to such activities. Restrictive measures can also be applied in response to cyber-attacks with a significant effect against third States or international organisations, where deemed necessary to achieve common foreign and security policy objectives set out in the relevant provisions of Article 21 of the Treaty on European Union. (3) On 16 April 2018 the Council adopted conclusions in which it firmly condemned the malicious use of information and communications technologies, including in the cyber-attacks publicly known as ‘WannaCry’ and ‘NotPetya’, which caused significant damage and economic loss in the Union and beyond. On 4 October 2018 the Presidents of the European Council and of the European Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (the ‘High Representative’) expressed serious concerns in a joint statement about an attempted cyber-attack to undermine the integrity of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in the Netherlands, an aggressive act which demonstrated contempt for the solemn purpose of the OPCW. -

APT and Cybercriminal Targeting of HCS June 9, 2020 Agenda

APT and Cybercriminal Targeting of HCS June 9, 2020 Agenda • Executive Summary Slides Key: • APT Group Objectives Non-Technical: managerial, strategic • APT Groups Targeting Health Sector and high-level (general audience) • Activity Timeline Technical: Tactical / IOCs; requiring • TTPs in-depth knowledge (sysadmins, IRT) • Malware • Vulnerabilities • Recommendations and Mitigations TLP: WHITE, ID#202006091030 2 Executive Summary • APT groups steal data, disrupt operations, and destroy infrastructure. Unlike most cybercriminals, APT attackers pursue their objectives over longer periods of time. They adapt to cyber defenses and frequently retarget the same victim. • Common HPH targets include: • Healthcare Biotechnology Medical devices • Pharmaceuticals Healthcare information technology • Scientific research • HPH organizations who have been victim of APT attacks have suffered: • Reputational harm Disruption to operations • Financial losses PII/PHI and proprietary data theft • HC3 recommends several mitigations and controls to counter APT threats. TLP: WHITE, ID#202006091030 3 APT Group Objectives • Motivations of APT Groups which target the health sector include: • Competitive advantage • Theft of proprietary data/intellectual capital such as technology, manufacturing processes, partnership agreements, business plans, pricing documents, test results, scientific research, communications, and contact lists to unfairly advance economically. • Intelligence gathering • Groups target individuals and connected associates to further social engineering -

Mcafee Labs Threats Report August 2014

McAfee Labs Threats Report August 2014 Heartbleed Heartbleed presents a new cybercrime opportunity. 600,000 To-do lists The Heartbleed vulnerability Lists of Heartbleed-vulnerable exposed an estimated 600,000 websites are helpful to users but websites to information theft. can also act as “to-do” lists for cyber thieves. Unpatched websites Black market Despite server upgrades, many Criminals continue to extract websites remain vulnerable. information from Heartbleed- vulnerable websites and are selling it on the black market. McAfee Phishing Quiz Phishing continues to be an effective tactic for infiltrating enterprise networks. Average Score by Department (percent of email samples correctly identified) Only 6% of all test takers correctly 65% identified all ten email samples as phishing or legitimate. 60% 80% 55% of all test takers fell for at least one of the seven phishing emails. 50% 88% of test takers in Accounting & 0 Finance and HR fell for at least one of the seven phishing emails. Accounting & Finance Human Resources Other Departments The McAfee Phishing Quiz tested business users’ ability to detect online scams. Operation Tovar During Operation Tovar—The Gameover Zeus and CryptoLocker takedown: For CryptoLocker For Gameover Zeus more than 125,000 more than 120,000 domains were blocked. domains were sinkholed. Since the announcement of Operation Tovar: 80,000 times Copycats ****** McAfee Stinger, a free ****** are on the rise, creating tool that detects and ****** new ransomware or removes malware financial-targeting (including Gameover Zeus malware using the leaked and CryptoLocker), was Zeus source code. downloaded more than 80,000 times. McAfee joined global law enforcement agencies and others to take down Gameover Zeus and CryptoLocker.