Smithsonian Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Definition of Folklore: a Personal Narrative

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Near Eastern Languages and Departmental Papers (NELC) Civilizations (NELC) 2014 A Definition of olklorF e: A Personal Narrative Dan Ben-Amos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers Part of the Folklore Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Oral History Commons Recommended Citation Ben-Amos, D. (2014). A Definition of olklorF e: A Personal Narrative. Estudis de Literatura Oral Popular (Studies in Oral Folk Literature), 3 9-28. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/141 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/nelc_papers/141 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Definition of olklorF e: A Personal Narrative Abstract My definition of folklore as "artistic communication in small groups" was forged in the context of folklore studies of the 1960s, in the discontent with the definitions that were current at the time, and under the influence of anthropology, linguistics - particularly 'the ethnography of speaking' - and Russian formalism. My field esearr ch among the Edo people of Nigeria had a formative impact upon my conception of folklore, when I observed their storytellers, singers, dancers and diviners in performance. The response to the definition was initially negative, or at best ambivalent, but as time passed, it took a more positive turn. Keywords context, communication, definition, performance, -

The Contagion of Capital

The Jus Semper Global Alliance In Pursuit of the People and Planet Paradigm Sustainable Human Development March 2021 ESSAYS ON TRUE DEMOCRACY AND CAPITALISM The Contagion of Capital Financialised Capitalism, COVID-19, and the Great Divide John Bellamy Foster, R. Jamil Jonna and Brett Clark he U.S. economy and society at the start of T 2021 is more polarised than it has been at any point since the Civil War. The wealthy are awash in a flood of riches, marked by a booming stock market, while the underlying population exists in a state of relative, and in some cases even absolute, misery and decline. The result is two national economies as perceived, respectively, by the top and the bottom of society: one of prosperity, the other of precariousness. At the level of production, economic stagnation is diminishing the life expectations of the vast majority. At the same time, financialisation is accelerating the consolidation of wealth by a very few. Although the current crisis of production associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has sharpened these disparities, the overall problem is much longer and more deep-seated, a manifestation of the inner contradictions of monopoly-finance capital. Comprehending the basic parameters of today’s financialised capitalist system is the key to understanding the contemporary contagion of capital, a corrupting and corrosive cash nexus that is spreading to all corners of the U.S. economy, the globe, and every aspect of human existence. TJSGA/Essay/SD (E052) March 2021/Bellamy Foster, Jonna and Clark 1 Free Cash and the Financialisation of Capital “Capitalism,” as left economist Robert Heilbroner wrote in The Nature and Logic of Capitalism in 1985, is “a social formation in which the accumulation of capital becomes the organising basis for socioeconomic life.”1 Economic crises in capitalism, whether short term or long term, are primarily crises of accumulation, that is, of the savings-and- investment (or surplus-and-investment) dynamics. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Masa Bulletin

masa bulletin IN THIS COLUMN we shall run discussions of MASSIVE MASA MEETING: As Yr. F. E. issues raised by the several chapters of the Amer writes this it is already two weeks beyond the ican Studies Association. This is in response to a date on which programs and registration forms request brought to us from the Council of the were to have been mailed. The printer, who has ASA at its Fall 1981 National Meeting. ASA had copy for ages, still has not delivered the pro members with appropriate issues on their minds grams. Having, in a moment of soft-headedness, are asked to communicate with their chapter of allowed himself to be suckered into accepting ficers, to whom we open these pages, asking only the position of local arrangements chair, he has that officers give us a buzz at 913-864-4878 to just learned that Haskell Springer, program alert us to what's likely to arrive, and that they chair, has been suddenly hospitalized, so that he keep items fairly short. will, for several weeks at least, have to take over No formal communications have come in yet, that duty as well. Having planned to provide though several members suggested that we music for some informal moments in the Spen prime the pump by reporting on the discussion cer Museum of Art before a joint session involv of joint meetings which grew out of the 1982 ing MASA and the Sonneck Society, he now finds that the woodwind quintet in which he MASA events described below. plays has lost its bassoonist, apparently irreplac- Joint meetings, of course, used to be SOP. -

A Business Lawyer's Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read

585 A Business Lawyer’s Bibliography: Books Every Dealmaker Should Read Robert C. Illig Introduction There exists today in America’s libraries and bookstores a superb if underappreciated resource for those interested in teaching or learning about business law. Academic historians and contemporary financial journalists have amassed a huge and varied collection of books that tell the story of how, why and for whom our modern business world operates. For those not currently on the front line of legal practice, these books offer a quick and meaningful way in. They help the reader obtain something not included in the typical three-year tour of the law school classroom—a sense of the context of our practice. Although the typical law school curriculum places an appropriately heavy emphasis on theory and doctrine, the importance of a solid grounding in context should not be underestimated. The best business lawyers provide not only legal analysis and deal execution. We offer wisdom and counsel. When we cast ourselves in the role of technocrats, as Ronald Gilson would have us do, we allow our advice to be defined downward and ultimately commoditized.1 Yet the best of us strive to be much more than legal engineers, and our advice much more than a mere commodity. When we master context, we rise to the level of counselors—purveyors of judgment, caution and insight. The question, then, for young attorneys or those who lack experience in a particular field is how best to attain the prudence and judgment that are the promise of our profession. For some, insight is gained through youthful immersion in a family business or other enterprise or experience. -

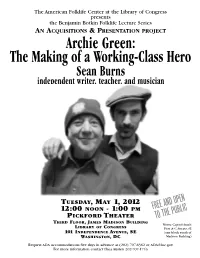

Archie Green, a Botkin Series Lecture by Sean Burns, American Folklife

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress presents the Benjamin Botkin Folklife Lecture Series AN ACQUISITIONS & PRESENTATION PROJECT Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns independent writer, teacher, and musician TUESDAY, MAY 1, 2012 D OPENFREE AN 12:00 NOON - 1:00 PM PICKFORD THEATER PUBLICTO THE THIRD FLOOR, JAMES MADISON BUILDING Metro: Capitol South LIBRARY OF CONGRESS First & C Streets, SE 101 I NDEPENDENCE AVENUE, SE (one block south of WASHINGTON, DC Madison Building) Request ADA accommodations five days in advance at (202) 707-6362 or [email protected] For more information contact Thea Austen 202-707-1743 Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns Respected as one of the great public intellectuals and his subsequent development of laborlore as a of the twentieth century, Archie Green (1917-2009), public-oriented interdisciplinary field. Burns will through his prolific writings and unprecedented explore laborlore’s impact on labor history, folklore, public initiatives on behalf of workers’ folklife, and American cultural studies and place these profoundly contributed to the philosophy and implications within the context of the larger “cultural practice of cultural pluralism. For Green, a child of turn” of the humanities and social sciences during Ukrainian immigrants, pluralism was the life-source the last quarter of the 20th century. When Green of democracy, an essential antidote to advocated in the late 1960s for the Festival of authoritarianism of every kind, which, for his American Folklife to include skilled manual laborers generation, most notably took the forms of fascism displaying their craft on the National Mall, this was and Stalinism. -

NASA's First A

NASA’s First A Aeronautics from 1958 to 2008 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications Public Outreach Division History Program Office Washington, DC 2013 The NASA History Series NASA SP-2012-4412 NASA’s First A Aeronautics from 1958 to 2008 Robert G. Ferguson Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ferguson, Robert G. NASA’s first A : aeronautics from 1958 to 2008 / Robert G. Ferguson. p. cm. -- (The NASA history series) (NASA SP ; 2012-4412) 1. United States. National Aeronautics and Space Administration--History. 2. United States. National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics--History. I. Title. TL521.312.F47 2012 629.130973--dc23 2011029949 This publication is available as a free download at http://www.nasa.gov/ebooks. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Chapter 1: The First A: The Other NASA ..................................1 Chapter 2: NACA Research, 1945–58 .................................... 25 Chapter 3: Creating NASA and the Space Race ........................57 Chapter 4: Renovation and Revolution ................................... 93 Chapter 5: Cold War Revival and Ideological Muddle ............141 Chapter 6: The Icarus Decade ............................................... 175 Chapter 7: Caught in Irons ................................................... 203 Chapter 8: Conclusion .......................................................... 229 Appendix: Aeronautics Budget 235 The NASA History Series 241 Index 259 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Before naming individuals, I must express my gratitude to those who have labored, and continue to do so, to preserve and share NASA’s history. I came to this project after years of studying private industry, where sources are rare and often inaccessible. By contrast, NASA’s History Program Office and its peers at the laboratories have been toiling for five decades, archiving, cataloging, interviewing, supporting research, and underwriting authors. -

THE JOHNSONS and THEIR KIN of RANDOLPH

THE JOHNSONS AND THEIR KIN of RANDOLPH JESSIE OWEN SHAW 514 - 19th Street, N.W. Washington 6, D. C. October 15, 1955 Copyright 1955 by Jessie Owen Shaw PRINTED IN USA BY McGREGOR & WERNER. INC. WASHINGTON. b. C. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The compiler desires to express her deep apprecia tion to each one of the many friends whose interest, encour agement and contribution of material have made this book possible. Those deserving particular mention are: Joseph H. Alexander, Selmer, Tenn.; Henry H. Beeson, Dallas, Tex.; Augustine W. Blair, High Point; Mrs. Evelyn Gray Brooks, Warwick, Va.; George D. Finch, Mrs. Eva Leach Hoover and Will R. Owen, Thomasville; Miss Blanche Johnson, Knox ville, Tenn.; the late Miss Emma Johnson, Trinity; Mrs. Myrtle Douglas Loy, Plainfield, Mo.; W. Ernest Merrill, Radford, Va.; John R. Peacock, High Point; Mrs. Erma John son VanWinkle, Clinton, Mo.; the late R. Clark Welborn, Baldwin C it y, Kans.; Mrs. Audrey Stone Williamson, Lexington. iii To the memory of Henry Johnson Who gave his life for American Independence iv PREFACE The historic interest of a place centers in the people, or families who found, occupy and adorn them, and connects them with the stirring legends and important events in the annals of the place. Robert Louis Stevenson spent years tracing his Highland ancestry because he felt that through ancestry one becomes a part of the movement of a country's tradition and history. To be proud of one's ancestry, or to wish to be proud of it, is an almost universal instinct. At a very early age every normal child begins to boast of the superiority of his, or her immediate ancestors to the immediate ancestors of other children. -

Thespectator N[ W S Present Pope Cuts Protested Turns Back the Clock - Lernoux Bybodettepenning Staff Reporter

Seattle nivU ersity ScholarWorks @ SeattleU The peS ctator 5-18-1989 Spectator 1989-05-18 Editors of The pS ectator Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator Recommended Citation Editors of The peS ctator, "Spectator 1989-05-18" (1989). The Spectator. 1833. http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator/1833 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The peS ctator by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. McGowan SU's year SU choir profiled in sports performs —p. 5 -pp. 6-7 -p. 8 Ml Non-Profit Org. 2 im U.S.POSTAGEPAID Seattle,WA the PermitNo.2783 Spectator May 18, 1989 SEATILEUN I V E I S I T V ASSUreviews this year's ups and downs TheRepresentativeCouncil ofASSU andorganizations, saidSteve Cummins, devoted a portion of its meeting last executive vicepresident,whonoted that Friday to reviewing its there were approximately 15 new orre- accomplishments andshortcomings this startup clubs this year. year. He expressed satisfaction with the In addition to theState of the Student accomplishment andsaida new funding process, which received high marks mechanism due tobe passed in the next from faculty,staff andadministrators for couple of weeks will allow even more Robert Heilbroner speaks to faculty members at a meeting Tuesday. the substantial documentation and groups to be funded by A.SSU next specific nature of its recommendations year. for student needs, thegroupas a whoJe "We've initiated a change in the expressed satisfaction with its work budgeting system so that we can allow Heilbroner visit drafting various codes and increasing for fund raising," Cummins said. -

"So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" a Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler

~~~~ 8 - ·t"§, · .. ~.JLJ.J.... ~ .... "So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" A Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler RICHARD KURIN Our friend Ralph did not feel above anyone. He quickly became a symbol of the Smithsonian helped people to learn to enjoy their differ under Secretary S. Dillon Ripley1 energizing ences. "Be aware of your time and your place, II the Mall. It showed that the folks from back he said to every one of us. "Learn to love the beau home had something to say in the center of 1 ty that is closest to you. II So I thank the Lord for the nation S capital. The Festival challenged sending us a friend who could teach us to appre America1s national cultural insecurity. ciate the skills of basket weavers, potters, and Neither European high art nor commercial bricklayers - of hod carriers and the mud mix pop entertainment represented the essence of ers. I am deeply indebted to Ralph Rinzler. He did American culture. Through the Festival1 the not leave me where he found me. Smithsonian gave recognition and respect to - Arthel 11 Doc" Watson the traditions/ wisdom1 songs1 and arts of the American people themselves. The mammoth Lay down, Ralph Rinzler, lay down and take 1976 Festival became the centerpiece of the your rest. American Bicentennial and a living reminder of the strength and energy of a truly wondrous o sang a Bahamian chorus on the and diverse cultural heritage - a legacy not to National Mall at a wake held for Ralph be ignored or squandered. -

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 the WEST and WORKERS, 1870

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 THE WEST AND WORKERS, 1870-1930, Blackwell Companion to the History of the American West, William Deverell, ed. (forthcoming) "Is there something unique about Seattle's labor history that helps explain what is going on?" the reporter for a San Jose newspaper asks me on the phone during the World Trade Organization protests that filled Seattle streets with 50,000 unionists, environmentalists, students, and other activists in the closing days of the last millennium. "Well, yes and no," I answer before launching into a much too complicated explanation of how history might inform the present without explaining it and how the West does have some particular traditions and institutional configurations that have made it the site of bold departures in the long history of American class and industrial relations but caution that we probably should not push the exceptionalism argument too far. "Thanks," he said rather vaguely as we hung up 20 minutes later. His story the next day included a twelve word quotation.1 The conversation, I realize much later, revealed some interesting tensions. Not long ago the information flow might have been reversed, the historian might have been calling the journalist to learn about western labor history, a body of 2 research that until the 1960s had not much to do with professional historians, particularly those who wrote about the West. And his disappointment at my long-winded equivocations had something to do with those disciplinary vectors. He had been hoping to tap into an argument that journalists know well but that academics have struggled with. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief.