The Mont Pelerin Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Removing Obstacles on the Path to Economic Freedom1

Removing Obstacles on the Path to Economic Freedom1 John B. Taylor Mont Pelerin Society Fort Worth, Texas May 22, 2019 My remarks on removing obstacles on the path to economic freedom touch on themes raised at Mont Pelerin Society meetings for many years. But here I emphasize that the obstacles often change their form over time and pop up in surprising ways. I see two basic kinds of obstacles. First are obstacles based on claims that the principle ideas of economic freedom are wrong or do not work. The principle ideas of economic freedom include the rule of law, predictable policies, reliance on markets, attention to incentives, and limitations on government.2 This first kind of obstacle largely promotes the opposite of these principles, arguing that the rule of law should be replaced by arbitrary government actions, that policy predictability is no virtue, that market prices can be replaced by central decrees, that incentives matter little, and that government does not need to be restrained. Many were making such claims at the time that the Mont Pelerin Society was founded in 1947. Communist governments were taking hold. Socialism was creeping up everywhere. “The common objective of those who met at Mont Pelerin was undoubtedly to halt and reverse current political, social, and economic trends toward socialism,” as R. M. Hartwell described the first meeting in his history of the Mont Pelerin Society.3 Despite many successes, these claims have returned today in renewed calls for socialism and criticism of free market capitalism as a way to improved standards of living. -

The Mont Pelerin Society

A SPECIAL MEETING THE MONT PELERIN SOCIETY JANUARY 15–17, 2020 FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE: IDEAS AND ACTIONS FOR A FREE SOCIETY CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY RUSSELL ROBERTS HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1 1 MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY Prepared for the January 2020 Mont Pelerin Society Meeting Hoover Institution, Stanford University Russ Roberts John and Jean De Nault Research Fellow Hoover Institution Stanford University [email protected] 1 2 According to many economists and pundits, we are living under the dominion of Milton Friedman’s free market, neoliberal worldview. Such is the claim of the recent book, The Economists’ Hour by Binyamin Applebaum. He blames the policy prescriptions of free- market economists for slower growth, inequality, and declining life expectancy. The most important figure in this seemingly disastrous intellectual revolution? “Milton Friedman, an elfin libertarian…Friedman offered an appealingly simple answer for the nation’s problems: Government should get out of the way.” A similar judgment is delivered in a recent article in the Boston Review by Suresh Naidu, Dani Rodrik, and Gabriel Zucman: Leading economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman were among the founders of the Mont Pelerin Society, the influential group of intellectuals whose advocacy of markets and hostility to government intervention proved highly effective in reshaping the policy landscape after 1980. Deregulation, financialization, dismantling of the welfare state, deinstitutionalization of labor markets, reduction in corporate and progressive taxation, and the pursuit of hyper-globalization—the culprits behind rising inequalities—all seem to be rooted in conventional economic doctrines. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Ralph Nader Radio Hour Ep 236 Transcript

RALPH NADER RADIO HOUR EP 236 TRANSCRIPT David Feldman: From the KPFK Studios in Southern California… Steve Skrovan: … It’s the Ralph Nader Radio Hour. “Stand up, stand up You’ve been sitting way too long” Steve Skrovan: Welcome to the Ralph Nader Radio Hour. My name is Steve Skrovan. My co-host David Feldman is observing Yom Kippur as we record this. He’s atoning, which is ironic because I think one of the things I expect him to atone for is not being here today. So it’s just kind of a vicious circle for him. But we also have the man of the hour, Ralph Nader. Hello Ralph. Ralph Nader: Hello everybody. Steve Skrovan: We have another special program today. In a lot of ways, our guest today, Phil Donahue, is the father of us all here in broadcasting, not to mention podcasting. That’s because the original Phil Donahue Show was born in Dayton, Ohio--not exactly a travel hub for the country’s movers and shakers. His show was one of the first, if not the first, if I’m not mistaken, to use conference-call technology to engage with guests on the phone who couldn’t make the trip to Dayton. On our show here, we do much the same thing, except we’re all in remote locations. I’m in Los Angeles, David is generally in New York, Ralph is in D.C., and our guests have come to us from all over the country and the world. So Phil Donahue literally invented the modern daytime talk show. -

Guide to the Mothers Against Drunk Driving Papers

Guide to the Mothers Against Drunk Driving Papers NMAH.AC.1262 Andrea Bishop and Vanessa Broussard Simmons Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series 1: Materials Relating to the Death of Carime Lightner, 1980-1992............... 3 Series 2: Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) Organization, 1980-1990, undated..................................................................................................................... 4 Series 3: Media and Publications, 1980-1990, undated.......................................... -

Amity Shlaes, Esteemed Scholar and Author, a 2021 Bradley Prize Winner Award Recognizes Extraordinary Talent, Dedication to American Exceptionalism

For Immediate Release Contact: Christine Czernejewski July 29, 2021 414-982-6684 Amity Shlaes, Esteemed Scholar and Author, a 2021 Bradley Prize Winner Award recognizes extraordinary talent, dedication to American exceptionalism Milwaukee, WI - The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation announced today that distinguished scholar and author Amity Shlaes is one of three winners of the 2021 Bradley Prizes. The honor recognizes individuals whose outstanding achievements reflect The Bradley Foundation’s mission to restore, strengthen and protect the principles and institutions of American exceptionalism. Shlaes will receive the award at the 17th annual Bradley Prizes ceremony on Monday, September 13th at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. “Amity’s exhaustive research and analysis of American economic history continues to inform influential decision makers,” said Rick Graber, President and CEO of The Bradley Foundation. “Her insight into how well-intentioned government programs have had the opposite effect of what they set out to achieve, provides valuable lessons for today. The Bradley Foundation is proud to honor Amity for her scholarship, which has contributed to important dialogue on economic policy.” Shlaes chairs the board of the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation, the official foundation dedicated to preserving and promoting the legacy of America’s 30th president. The Coolidge Foundation is the sponsor of the popular Coolidge Scholarship, a full college scholarship for academic merit, and the Coolidge Senators program, which hosts 100 students each summer for a stay in Washington at Coolidge House to learn them about the values of President Coolidge. Shlaes’ most recent book is Great Society: A New History. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Forms of Government

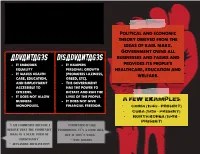

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

The Mont Pelerin Society: a MANDATE RENEWED

1 The Mont Pelerin Society: A MANDATE RENEWED By Deepak Lal Ladies and Gentlemen, Welcome to this special meeting of the MPS. In this address I would like to explain why it has been called at such short notice and how I hope it provides a renewal of the mandate our founders set for the society.1 After being anointed with the Presidency of this august body in Tokyo (in early September), my wife and I went on to a lecture tour in China. We were in Shanghai on a tour of the magnificent Suzhou industrial estate outside Shanghai, with MPS member Steven Cheung. On the afternoon of the 15th September Steve received a call on his Blackberry that Lehman Brothers had gone into bankruptcy. Steve opined that this marked the end of American capitalism. I thought this somewhat hyperbolic. But, on getting back to London at the end of September, as I was tending my roses, my neighbor, a Thatcherite heart surgeon, said over the hedge that, given the recent events in the capital markets, did I still stand by the views I had expressed in my last book on "Reviving the Invisible Hand".2 I replied that even a severe trade cycle downturn would not undermine the well tested classical liberal principles I had espoused. Though, Gordon Brown might be in trouble having repeatedly congratulated himself for having abolished boom and bust. Two subsequent events shattered this complacency. I had been following a political betting site called Betfair on which some youngsters at the Tokyo MPS meeting were placing bets on a McCain victory. -

Education Policy and Friedmanomics: Free Market Ideology and Its Impact

Education Policy and Friedmanomics: Free Market Ideology and Its Impact on School Reform Thomas J. Fiala Department of Teacher Education Arkansas State University Deborah Duncan Owens Department of Teacher Education Arkansas State University April 23, 2010 Paper presented at the 68th Annual National Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association Chicago, Illinois 2 ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of neoliberal ideology, and in particular, the economic and social theories of Milton Friedman on education policy. The paper takes a critical theoretical approach in that ultimately the paper is an ideological critique of conservative thought and action that impacts twenty-first century education reform. Using primary and secondary documents, the paper takes an historical approach to begin understanding how Friedman’s free market ideas helped bring together disparate conservative groups, and how these groups became united in influencing contemporary education reform. The paper thus considers the extent to which free market theory becomes the essence of contemporary education policy. The result of this critical and historical anaysis gives needed additional insights into the complex ideological underpinnings of education policy in America. The conclusion of this paper brings into question the efficacy and appropriateness of free market theory to guide education policy and the use of vouchers and choice, and by extension testing and merit-based pay, as free market panaceas to solving the challenges schools face in the United States. Administrators, teachers, education policy makers, and those citizens concerned about education in the U.S. need to be cautious in adhering to the idea that the unfettered free market can or should drive education reform in the United States. -

The Contagion of Capital

The Jus Semper Global Alliance In Pursuit of the People and Planet Paradigm Sustainable Human Development March 2021 ESSAYS ON TRUE DEMOCRACY AND CAPITALISM The Contagion of Capital Financialised Capitalism, COVID-19, and the Great Divide John Bellamy Foster, R. Jamil Jonna and Brett Clark he U.S. economy and society at the start of T 2021 is more polarised than it has been at any point since the Civil War. The wealthy are awash in a flood of riches, marked by a booming stock market, while the underlying population exists in a state of relative, and in some cases even absolute, misery and decline. The result is two national economies as perceived, respectively, by the top and the bottom of society: one of prosperity, the other of precariousness. At the level of production, economic stagnation is diminishing the life expectations of the vast majority. At the same time, financialisation is accelerating the consolidation of wealth by a very few. Although the current crisis of production associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has sharpened these disparities, the overall problem is much longer and more deep-seated, a manifestation of the inner contradictions of monopoly-finance capital. Comprehending the basic parameters of today’s financialised capitalist system is the key to understanding the contemporary contagion of capital, a corrupting and corrosive cash nexus that is spreading to all corners of the U.S. economy, the globe, and every aspect of human existence. TJSGA/Essay/SD (E052) March 2021/Bellamy Foster, Jonna and Clark 1 Free Cash and the Financialisation of Capital “Capitalism,” as left economist Robert Heilbroner wrote in The Nature and Logic of Capitalism in 1985, is “a social formation in which the accumulation of capital becomes the organising basis for socioeconomic life.”1 Economic crises in capitalism, whether short term or long term, are primarily crises of accumulation, that is, of the savings-and- investment (or surplus-and-investment) dynamics. -

Peter J. Boettke

PETER J. BOETTKE BB&T Professor for the Study of Capitalism, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, & University Professor of Economics and Philosophy Department of Economics, MSN 3G4 George Mason University Fairfax, VA 22030 Tel: 703-993-1149 Fax: 703-993-1133 Web: http://www.peter-boettke.com http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/cf_dev/AbsByAuth.cfm?per_id=182652 http://www.coordinationproblem.org PERSONAL Date of birth: January 3, 1960 Nationality: United States EDUCATION Ph.D. in Economics, George Mason University, January, 1989 M.A. in Economics, George Mason University, January, 1987 B.A. in Economics, Grove City College, May, 1983 TITLE OF DOCTORAL THESIS: The Political Economy of Soviet Socialism, 1918-1928 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Academic Positions 1987 –88 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, George Mason University 1988 –90 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, School of Business Administration, Oakland University, Rochester, MI 48309 1990 –97 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, New York University, New York, NY 10003 1997 –98 Associate Professor, Department of Economics and Finance, School of Business, Manhattan College, Riverdale, NY 10471 1998 – 2003 Associate Professor, Department of Economics, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030 (tenured Fall 2000) 2003 –07 Professor, Department of Economics, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030 2007 – University Professor, George Mason University 2011 – Affiliate Faculty, Department of Philosophy, George Mason University FIELDS OF INTEREST