June 2019: Occupational Folklife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Masa Bulletin

masa bulletin IN THIS COLUMN we shall run discussions of MASSIVE MASA MEETING: As Yr. F. E. issues raised by the several chapters of the Amer writes this it is already two weeks beyond the ican Studies Association. This is in response to a date on which programs and registration forms request brought to us from the Council of the were to have been mailed. The printer, who has ASA at its Fall 1981 National Meeting. ASA had copy for ages, still has not delivered the pro members with appropriate issues on their minds grams. Having, in a moment of soft-headedness, are asked to communicate with their chapter of allowed himself to be suckered into accepting ficers, to whom we open these pages, asking only the position of local arrangements chair, he has that officers give us a buzz at 913-864-4878 to just learned that Haskell Springer, program alert us to what's likely to arrive, and that they chair, has been suddenly hospitalized, so that he keep items fairly short. will, for several weeks at least, have to take over No formal communications have come in yet, that duty as well. Having planned to provide though several members suggested that we music for some informal moments in the Spen prime the pump by reporting on the discussion cer Museum of Art before a joint session involv of joint meetings which grew out of the 1982 ing MASA and the Sonneck Society, he now finds that the woodwind quintet in which he MASA events described below. plays has lost its bassoonist, apparently irreplac- Joint meetings, of course, used to be SOP. -

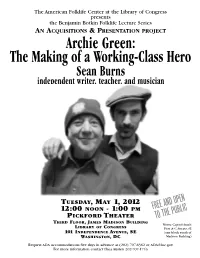

Archie Green, a Botkin Series Lecture by Sean Burns, American Folklife

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress presents the Benjamin Botkin Folklife Lecture Series AN ACQUISITIONS & PRESENTATION PROJECT Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns independent writer, teacher, and musician TUESDAY, MAY 1, 2012 D OPENFREE AN 12:00 NOON - 1:00 PM PICKFORD THEATER PUBLICTO THE THIRD FLOOR, JAMES MADISON BUILDING Metro: Capitol South LIBRARY OF CONGRESS First & C Streets, SE 101 I NDEPENDENCE AVENUE, SE (one block south of WASHINGTON, DC Madison Building) Request ADA accommodations five days in advance at (202) 707-6362 or [email protected] For more information contact Thea Austen 202-707-1743 Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns Respected as one of the great public intellectuals and his subsequent development of laborlore as a of the twentieth century, Archie Green (1917-2009), public-oriented interdisciplinary field. Burns will through his prolific writings and unprecedented explore laborlore’s impact on labor history, folklore, public initiatives on behalf of workers’ folklife, and American cultural studies and place these profoundly contributed to the philosophy and implications within the context of the larger “cultural practice of cultural pluralism. For Green, a child of turn” of the humanities and social sciences during Ukrainian immigrants, pluralism was the life-source the last quarter of the 20th century. When Green of democracy, an essential antidote to advocated in the late 1960s for the Festival of authoritarianism of every kind, which, for his American Folklife to include skilled manual laborers generation, most notably took the forms of fascism displaying their craft on the National Mall, this was and Stalinism. -

"So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" a Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler

~~~~ 8 - ·t"§, · .. ~.JLJ.J.... ~ .... "So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" A Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler RICHARD KURIN Our friend Ralph did not feel above anyone. He quickly became a symbol of the Smithsonian helped people to learn to enjoy their differ under Secretary S. Dillon Ripley1 energizing ences. "Be aware of your time and your place, II the Mall. It showed that the folks from back he said to every one of us. "Learn to love the beau home had something to say in the center of 1 ty that is closest to you. II So I thank the Lord for the nation S capital. The Festival challenged sending us a friend who could teach us to appre America1s national cultural insecurity. ciate the skills of basket weavers, potters, and Neither European high art nor commercial bricklayers - of hod carriers and the mud mix pop entertainment represented the essence of ers. I am deeply indebted to Ralph Rinzler. He did American culture. Through the Festival1 the not leave me where he found me. Smithsonian gave recognition and respect to - Arthel 11 Doc" Watson the traditions/ wisdom1 songs1 and arts of the American people themselves. The mammoth Lay down, Ralph Rinzler, lay down and take 1976 Festival became the centerpiece of the your rest. American Bicentennial and a living reminder of the strength and energy of a truly wondrous o sang a Bahamian chorus on the and diverse cultural heritage - a legacy not to National Mall at a wake held for Ralph be ignored or squandered. -

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 the WEST and WORKERS, 1870

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 THE WEST AND WORKERS, 1870-1930, Blackwell Companion to the History of the American West, William Deverell, ed. (forthcoming) "Is there something unique about Seattle's labor history that helps explain what is going on?" the reporter for a San Jose newspaper asks me on the phone during the World Trade Organization protests that filled Seattle streets with 50,000 unionists, environmentalists, students, and other activists in the closing days of the last millennium. "Well, yes and no," I answer before launching into a much too complicated explanation of how history might inform the present without explaining it and how the West does have some particular traditions and institutional configurations that have made it the site of bold departures in the long history of American class and industrial relations but caution that we probably should not push the exceptionalism argument too far. "Thanks," he said rather vaguely as we hung up 20 minutes later. His story the next day included a twelve word quotation.1 The conversation, I realize much later, revealed some interesting tensions. Not long ago the information flow might have been reversed, the historian might have been calling the journalist to learn about western labor history, a body of 2 research that until the 1960s had not much to do with professional historians, particularly those who wrote about the West. And his disappointment at my long-winded equivocations had something to do with those disciplinary vectors. He had been hoping to tap into an argument that journalists know well but that academics have struggled with. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

IWW Records, Part 3 1 Linear Foot (2 MB) 1930-1996, Bulk 1993-1996

Part 1 Industrial Workers of the World Collection Papers, 1905-1972 92.3 linear feet Accession No. 130 L.C. Number MS 66-1519 The papers of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in February of 1965, by the Industrial Workers of the World. Other deposits have been made subsequently. Over the turn of the century, the cause of labor and unionism had sustained some hard blows. High immigration, insecurity of employment and frequent economic recessions added to the problems of any believer in unionism. In January, 1905 a group of people from different areas of the country came to Chicago for a conference. Their interest was the cause of labor (viewed through a variety of political glasses) and their hope was somehow to get together, to start a successful drive for industrial unionism rather than craft unionism. A manifesto was formulated and a convention called for June, 1905 for discussion and action on industrial unionism and better working class solidarity. At that convention, the Industrial Workers of the World was organized. The more politically-minded members dropped out after a few years, as the IWW in general wished to take no political line at all, but instead to work through industrial union organization against the capitalist system. The main beliefs of this group are epitomized in the preamble to the IWW constitution, which emphasizes that the workers and their employers have "nothing in common." They were not anarchists, but rather believed in a minimal industrial government over an industrially organized society. -

The Journal of New York Folklore

Fall–Winter 2001 Volume 27: 3–4 The Journal of New York Folklore September 11: In Memoriam Benjamin A. Botkin, on the centenary of his birth Oxen Teams: A Farm Tradition An Italian Family Chapel in the Bronx Building Cultural Bridges in Binghamton Coming of Age in the City: Two short stories The Tradition of Fiddlin’: Granny Sweet and Alice Clemens From the Director Unusual Times the benefits are innumerable, and we, as a state, Concertina All-Star Orchestra. The evening In a recent New York are the richer for such efforts. In the twentieth provided a wonderful variety of musical styles Folklore Society –spon- century there were many hard-working advo- and traditions, concluding with the rich sound sored event, folklorist cates for New York’s traditional culture who of polkas played on at least a dozen concertinas. Mark Klempner spoke formed organizations such as the New York We welcomed new board members Greer on Dutch citizens who Folklore Society or created folklore collections Smith of Highland, Debbie Silverman of Ham- rescued Jews in the that serve as testaments to the creativity of New burg, and Karen Canning of Piffard, as well as Netherlands during the York’s diverse peoples. The citizens of New returning board member Madaha Kinsey-Lamb Holocaust. Klempner York and our folk cultural organizations need of Brooklyn. We at the New York Folklore So- has been collecting oral to continue into the twenty-first century to cre- ciety would also like to thank departing board histories of the rescuers, and he presented his ate opportunities to draw attention to the rich member Dan Berggren of Fredonia for his past work in a Humanities Month program jointly cultural fabric of the state. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress for Fiscal Year 2012

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress For the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2012 Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2012 Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2013 Library of Congress 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20540 For the Library of Congress online, visit www.loc.gov. The annual report is published through the Office of Communications, Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20540-1610, telephone (202) 707-2905. Executive Editor: Gayle Osterberg Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Art Director: John Sayers Photo Editor: Abby Brack Lewis Design and Composition: Blue House Design Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 6-6273 ISSN 0083-1565 Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 978-0-8444-9565-1 FRONT COVER The exterior of the Thomas Jefferson Building boasts banners for 2012 Library exhibitions. Photo courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol INSIDE FRONT COVER AND INSIDE BACK COVER Selected titles from the Library’s exhibition, Books That Shaped America CONTENTS A Letter from the Librarian of Congress ...................... 5 Appendices A. Library of Congress Advisory Bodies............... 62 Library of Congress Officers ........................................ 6 B. Publications ....................................................... 68 C. Selected Acquisitions ........................................ 70 Library -

Ill Ino S University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

H ILL INO S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. olume 4, Number 3 (whole issue 18) February 3, 1964 FOLKSINGS; ANNIVERSARY; VOTING -- We Are Three Years Old And Busy-- 461ksingg and elections are the duties facing Campus Folksong Club's active embership this month, as the Club begins its fourth straight year of operation. The first folksing of the new semester will be held on February 7th at 8:00 'clock in 112 Gregory Hall. The second.sing of the month will be held two weeks ater at the same location and time, on the 21st of February. This will be the hird Anniversary Sing, and will feature a collection of the Club's best talent rom the past year. Although plans are not yet definite, it is the intention of the Club to present, s a momento of its recent recording success, some of the artists who graced the econd long-playing record album in the Club's career--Green Fields of Illinois. (le Mayfield will be on hand, and he has promised to bring along his wife Doris idsome of his musical friends from Southern Illinois. He is especially hopeful lat Stelle Elam, the fiddler featured on the Club's record, will be able to appear Sthe sing. It was just one year ago that Mrs. Elam made her debut on our stage, id those who were there will remember the excitment she generated with her old- lmey fiddling style. Less entertaining, but ultimately perhaps more important, is the annual businesE !eting, scheduled for February 12th at 8:00 p.m. -

BLUES SONGBOOK Booklet

ROUNDER CD 82161-0000-2 p © 2003 Rounder Records Corp., One Camp Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140 USA. ROUNDER is a registered trademark of Rounder Records Corp. www.rounder.com; email: [email protected] www.alan-lomax.com ALAN LOMAX AND THE BLUES Alan Lomax was a lifelong fan of blues music, and his efforts to document and promote it have made a profound impact on popular culture. From his earliest audio documentation in 1933 of blues and pre-blues with his father, John A. Lomax, for the Library of Congress through his 1985 documentary film, The Land Where the Blues Began, Lomax gathered some of the finest evidence of blues, work songs, hollers, fife and drum music, and other African-American song forms that survived the nineteenth century and prospered in the twentieth. His efforts went far beyond those of the typical musicologist. Lomax not only collected the music for research, but through his radio programs, album releases, books, and concert promotions he presented it to a popular audience. HOWLIN’ WOLF While living in England in the early 1950s, he introduced many blues songs to the performers of the skiffle movement, who in quick turn ignited the British rock scene. Lead Belly and other blues artists, interpreted by Lonnie Donegan and Van Morrison, preceded the rock & roll tradition of covering and rewriting blues songs. The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, the Animals, Cream, Jimi Hendrix—all found inspiration from the blues. And this is how I came to the blues, as many people have: by way of rock & roll. In the very structure of rock music—and, in fact, much of popular music—the source is undeniable. -

Smithsonian Folklife Festival Records: 1971 Festival of American Folklife

Smithsonian Folklife Festival records: 1971 Festival of American Folklife by CFCH Staff 2017 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. Phone: 202-633-6440 [email protected] http://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview......................................................................................................... 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 Festival speakers and consultants.................................................................................. 3 Names and Subject Terms ............................................................................................. 4 Container Listing.............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Program Books, Festival Publications, and Ephemera, 1971................... 5 Series