Ill Ino S University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview The 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival is quickly approaching, February 14 -16 at the Sheraton Framingham Hotel, in Framingham, MA. The event, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, is one of the premier roots music festivals in the Northeast. The festival site is minutes west of Boston, just off of the Mass Pike, and convenient to travelers from throughout the region. This award winning and family friendly festival features three days of top national performers across two stages, over sixty workshops and education programs, and around the clock activities. Among the many artists on tap are The Gibson Brothers, Blue Highway, Junior Sisk, IIIrd Tyme Out, Sister Sadie featuring Dale Ann Bradley, and a special reunion performance by The Desert Rose Band. This locally produced and internationally recognized bluegrass festival, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, was honored in 2006 when the International Bluegrass Music Association named it "Event of the Year." In May 2012, the festival was listed by USATODAY as one of Ten Great Places to Go to Bluegrass Festivals Single day and weekend tickets are on sale now and we strongly suggest purchasing tickets in advance. Patrons will save time at the festival and guarantee themselves a ticket. Hotel rooms at the Sheraton are sold out, but overnight lodging is still available and just minutes away, at the Doubletree by Hilton, in Westborough, MA. Details on the festival, including bands, schedules, hotel information, and online ticket purchase at www.bbu.org And visit the 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival on Facebook for late breaking festival news. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Masa Bulletin

masa bulletin IN THIS COLUMN we shall run discussions of MASSIVE MASA MEETING: As Yr. F. E. issues raised by the several chapters of the Amer writes this it is already two weeks beyond the ican Studies Association. This is in response to a date on which programs and registration forms request brought to us from the Council of the were to have been mailed. The printer, who has ASA at its Fall 1981 National Meeting. ASA had copy for ages, still has not delivered the pro members with appropriate issues on their minds grams. Having, in a moment of soft-headedness, are asked to communicate with their chapter of allowed himself to be suckered into accepting ficers, to whom we open these pages, asking only the position of local arrangements chair, he has that officers give us a buzz at 913-864-4878 to just learned that Haskell Springer, program alert us to what's likely to arrive, and that they chair, has been suddenly hospitalized, so that he keep items fairly short. will, for several weeks at least, have to take over No formal communications have come in yet, that duty as well. Having planned to provide though several members suggested that we music for some informal moments in the Spen prime the pump by reporting on the discussion cer Museum of Art before a joint session involv of joint meetings which grew out of the 1982 ing MASA and the Sonneck Society, he now finds that the woodwind quintet in which he MASA events described below. plays has lost its bassoonist, apparently irreplac- Joint meetings, of course, used to be SOP. -

Need Christmas Presents? We’Ve Got You Covered!

Return Service Requested NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION U.S. POSTAGE PAID PO Box 21748 Juneau, AK Juneau, AK 99802-1748 Permit #194 www.akfolkfest.org November 2014 Newsletter 41st Annual Alaska Folk Festival April 6-12, 2015 Need Christmas Presents? We’ve Got You Covered! e have reordered some of last year’s W amazing festival merchandise. Our merchandise last year sold like hot-cakes and we’ve heard from a lot of members that they wish they could still get their hands on the 40th festival items. You can find our festival merchandise at the gift store at the JACC year-round and we’ve got an extra large stock on hand for this year’s Public Market on November 28th,29th, & 30th. And for the first time ever we will have a pop-up store for Gallery Walk! The Senate Building, 2nd floor (where the fly fishing shop used to be) will be hosting the Alaska Folk Festival as part of this year’s December First Friday event, also known as Gallery Walk, on December 5th from 4:00 - 7:30pm. Come chat with board members, pick up some beautiful merchandise, and sign up for, or renew your membership. Merchandise is one of the primary ways that the festival gen- erates funds and we greatly appreciate your support, and we LOVE seeing those folk fest hoodies around town. The 2015 AFF Guest Artist: The Byron Berline Band he Alaska Folk Festival is thrilled to have the Byron Year.' As one of the world’s premier fiddle players, Berline T Berline Band as our 2015 guest artist. -

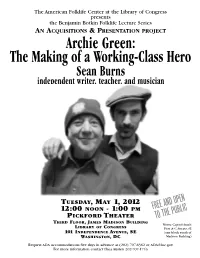

Archie Green, a Botkin Series Lecture by Sean Burns, American Folklife

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress presents the Benjamin Botkin Folklife Lecture Series AN ACQUISITIONS & PRESENTATION PROJECT Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns independent writer, teacher, and musician TUESDAY, MAY 1, 2012 D OPENFREE AN 12:00 NOON - 1:00 PM PICKFORD THEATER PUBLICTO THE THIRD FLOOR, JAMES MADISON BUILDING Metro: Capitol South LIBRARY OF CONGRESS First & C Streets, SE 101 I NDEPENDENCE AVENUE, SE (one block south of WASHINGTON, DC Madison Building) Request ADA accommodations five days in advance at (202) 707-6362 or [email protected] For more information contact Thea Austen 202-707-1743 Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns Respected as one of the great public intellectuals and his subsequent development of laborlore as a of the twentieth century, Archie Green (1917-2009), public-oriented interdisciplinary field. Burns will through his prolific writings and unprecedented explore laborlore’s impact on labor history, folklore, public initiatives on behalf of workers’ folklife, and American cultural studies and place these profoundly contributed to the philosophy and implications within the context of the larger “cultural practice of cultural pluralism. For Green, a child of turn” of the humanities and social sciences during Ukrainian immigrants, pluralism was the life-source the last quarter of the 20th century. When Green of democracy, an essential antidote to advocated in the late 1960s for the Festival of authoritarianism of every kind, which, for his American Folklife to include skilled manual laborers generation, most notably took the forms of fascism displaying their craft on the National Mall, this was and Stalinism. -

Guitar Blues Book

Guitar Blues Book Ur-Vogel Jeholopterus spielt den Ur-Blues 13. November 2019 Vorwort Dies ist das persönliche Guitar Blues Buch von Hans Ulrich Stalder, CH 5425 Schneisingen. Die zur Webseite www.quantophon.com verlinkten Videos und Musikdateien sind persönliche Arbeitskopien. Ausser wenn speziell erwähnt sind alles MP3- oder MP4-Files. Hier vorkommende Blues-Musiker sind: Big Bill Broonzy geboren als Lee Conley Bradley am 26. Juni 1903 in Jefferson County (Arkansas), †15. August 1958 in Chicago, Illinois, war ein US-amerikanischer Blues-Musiker und Blues-Komponist. Lightnin’ Hopkins geboren als Sam Hopkinsan am 15. März 1912 in Centerville, Texas, † 30. Januar 1982 in Houston, Texas, war ein US- amerikanischer Blues-Sänger und Blues-Gitarrist. Er gilt als einflussreicher Vertreter des Texas Blues. Hans Ulrich Stalder © Seite 2 / 67 Champion Jack Dupree William Thomas "Champion Jack" Dupree, geboren am 23. Oktober 1909 in New Orleans, † 21. Januar 1992 in Hannover, war ein amerikanischer Blues-Sänger und Blues-Pianist. Sam Chatmon geboren am 10. Januar 1897 in Bolton, Mississippi, † 2. Februar 1983 in Hollandale, Mississippi, war ein US-amerikanischer Blues- Musiker. Er stammte aus der musikalischen Chatmon-Familie und begann – wie auch seine Brüder Bo und Lonnie – bereits als Kind, Musik zu machen. Leroy Carr geboren am 27. März 1905 in Nashville, Tennessee, † 29. April 1935 in Indianapolis, war ein US-amerikanischer Blues-Pianist und Sänger. Bekannt war er vor allem zusammen mit seinem langjährigen Partner, dem Gitarristen Francis "Scrapper" Blackwell, mit dem er als Duo auftrat und Aufnahmen machte. Elmore James geboren am 27. Januar 1918 in Mississippi, † 24. Mai 1963 in Chicago, Illinois, war ein US-amerikanischer Bluesmusiker. -

The Dillards Decade Waltz Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Dillards Decade Waltz mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Decade Waltz Country: Japan Released: 1979 Style: Bluegrass MP3 version RAR size: 1539 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1367 mb WMA version RAR size: 1323 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 784 Other Formats: TTA DTS MOD AAC AHX AUD DMF Tracklist Hide Credits The Ten Years Waltz A1 0:47 Written-By – Douglas Bounsall Greenback Dollar A2 2:50 Written-By – H. Dillard*, P. York*, Rodney Dillard Easy Ride A3 2:36 Written-By – Herb Pedersen Headed For The Country A4 3:01 Written-By – Larry Murray Gruelin' Banjos A5 2:18 Written-By – Jeff Gilkinson Turn It Around A6 3:46 Written-By – Jerry Reed 10 Years Waltz B1 0:47 Written-By – Douglas Bounsall Hymn To The Road B2 2:36 Written-By – Jeff Gilkinson Lights Of Magdella B3 3:44 Written-By – Larry Murray Happy I'll Be B4 3:23 Written-By – Ray Park Mason Dixon B5 2:58 Written-By – Jeff Gilkinson We Can Work It Out B6 2:53 Written-By – John Lennon, Paul McCartney* Companies, etc. Record Company – Trio Records Credits Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar, Banjo, Vocals – Herb Pedersen Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar, Mandolin, Fiddle, Vocals – Douglas Bounsall Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar, Resonator Guitar [Dobro] – Rodney Dillard Backing Vocals – Dean Webb , Doug Bounsall*, Herb Pedersen, Rodney Dillard Bass, Banjo, Cello, Bass Harmonica, Vocals – Jeff Gilkinson Drums, Percussion – Paul York Engineer – Paul Dobbe Mandolin, Vocals – Dean Webb Mixed By – Herb Pedersen, Rodney Dillard Producer – Herb Pedersen, Rodney -

"So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" a Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler

~~~~ 8 - ·t"§, · .. ~.JLJ.J.... ~ .... "So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" A Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler RICHARD KURIN Our friend Ralph did not feel above anyone. He quickly became a symbol of the Smithsonian helped people to learn to enjoy their differ under Secretary S. Dillon Ripley1 energizing ences. "Be aware of your time and your place, II the Mall. It showed that the folks from back he said to every one of us. "Learn to love the beau home had something to say in the center of 1 ty that is closest to you. II So I thank the Lord for the nation S capital. The Festival challenged sending us a friend who could teach us to appre America1s national cultural insecurity. ciate the skills of basket weavers, potters, and Neither European high art nor commercial bricklayers - of hod carriers and the mud mix pop entertainment represented the essence of ers. I am deeply indebted to Ralph Rinzler. He did American culture. Through the Festival1 the not leave me where he found me. Smithsonian gave recognition and respect to - Arthel 11 Doc" Watson the traditions/ wisdom1 songs1 and arts of the American people themselves. The mammoth Lay down, Ralph Rinzler, lay down and take 1976 Festival became the centerpiece of the your rest. American Bicentennial and a living reminder of the strength and energy of a truly wondrous o sang a Bahamian chorus on the and diverse cultural heritage - a legacy not to National Mall at a wake held for Ralph be ignored or squandered. -

Download a Brief History of the San Diego Bluegrass Society

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SAN DIEGO BLUEGRASS SOCIETY By Dwight Worden May 13, 2014 THE EARLY YEARS The late 1960s and early 70s were a time of change in America. Students were active, an unpopular war was underway, and many young Americans were breaking with the traditions of their parents. It was the season of long hair and love. The new generation was experimenting with, among other things, music. Amidst the excitement and turmoil of the times many, both young and old, were searching for authenticity and solid values in music and lifestyles. The folk boom of the 1950's and early 60's had awakened many to the raw authenticity of acoustic, folk, and bluegrass music. It was during this time period that groups like the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers were making a bluegrass mark in San Diego. Two local members of that band went on to national rock and roll stardom, Chris Hillman (mandolin) who became a founding member of the Byrds (bass), and Bernie Leadon (guitar)who joined the Eagles (guitar). Kenny Wertz of the “Barkers” (banjo) went on to bluegrass fame in Country Gazette (guitar) and with the Flying Burrito Brothers. There were jam sessions at the Blue Guitar music store, then located in Old Town (now on Mission Gorge Road). Venues like the Heritage in Mission Beach and the Candy Company brought acts like Vern and Ray, the Dillards, and others to town. “Cactus Jim” Soldi of Valley Music in El Cajon was the first to bring Bill Monroe to town at the Bostonia Ballroom in El Cajon. -

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 the WEST and WORKERS, 1870

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 THE WEST AND WORKERS, 1870-1930, Blackwell Companion to the History of the American West, William Deverell, ed. (forthcoming) "Is there something unique about Seattle's labor history that helps explain what is going on?" the reporter for a San Jose newspaper asks me on the phone during the World Trade Organization protests that filled Seattle streets with 50,000 unionists, environmentalists, students, and other activists in the closing days of the last millennium. "Well, yes and no," I answer before launching into a much too complicated explanation of how history might inform the present without explaining it and how the West does have some particular traditions and institutional configurations that have made it the site of bold departures in the long history of American class and industrial relations but caution that we probably should not push the exceptionalism argument too far. "Thanks," he said rather vaguely as we hung up 20 minutes later. His story the next day included a twelve word quotation.1 The conversation, I realize much later, revealed some interesting tensions. Not long ago the information flow might have been reversed, the historian might have been calling the journalist to learn about western labor history, a body of 2 research that until the 1960s had not much to do with professional historians, particularly those who wrote about the West. And his disappointment at my long-winded equivocations had something to do with those disciplinary vectors. He had been hoping to tap into an argument that journalists know well but that academics have struggled with. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

Edited and Transcribed by STEFAN GROSSMAN

AUTHENTIC GUITAR TAB EDITION EDITED AND TRANSCRIBED BY STEFAN GROSSMAN Contents Page Audio Track Introduction ...................................................................2 Explanation of the TAB/Music System ...........................4 Scrapper Blackwell .......................................................6 Blue Day Blues...................................................................... 7 ................ 1 Kokomo Blues .........................................................................12 ...............2 Blind Blake ................................................................... 18 Georgia Bound ........................................................................19 ............... 3 Big Bill Broonzy .......................................................... 25 Big Bill Blues ...................................................................... 26 ...............4 Mississippi River Blues .........................................................30 ............... 5 Mr. Conductor Man ................................................................32 ............... 6 Saturday Night Rub ...............................................................36 ............... 7 Stove Pipe Stomp ....................................................................39 ............... 8 Worryiní You Off My Mind .................................................... 42 ............... 9 Rev. Gary Davis ............................................................. 45 Cincinnati Flow Rag ............................................................