High Streets & Town Centres: Adaptive Strategies Guidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igniting Change and Building on the Spirit of Dalston As One of the Most Fashionable Postcodes in London. Stunning New A1, A3

Stunning new A1, A3 & A4 units to let 625sq.ft. - 8,000sq.ft. Igniting change and building on the spirit of Dalston as one of the most fashionable postcodes in london. Dalston is transforming and igniting change Widely regarded as one of the most fashionable postcodes in Britain, Dalston is an area identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. It is located directly north of Shoreditch and Haggerston, with Hackney Central North located approximately 1 mile to the east. The area has benefited over recent years from the arrival a young and affluent residential population, which joins an already diverse local catchment. , 15Sq.ft of A1, A3000+ & A4 commercial units Located in the heart of Dalston and along the prime retail pitch of Kingsland High Street is this exciting mixed use development, comprising over 15,000 sq ft of C O retail and leisure space at ground floor level across two sites. N N E C T There are excellent public transport links with Dalston Kingsland and Dalston Junction Overground stations in close F A proximity together with numerous bus routes. S H O I N A B L E Dalston has benefitted from considerable investment Stoke Newington in recent years. Additional Brighton regeneration projects taking Road Hackney Downs place in the immediate Highbury vicinity include the newly Dalston Hackney Central Stoke Newington Road Newington Stoke completed Dalston Square Belgrade 2 residential scheme (Barratt Road Haggerston London fields Homes) which comprises over 550 new homes, a new Barrett’s Grove 8 Regents Canal community Library and W O R Hoxton 3 9 10 commercial and retail units. -

Elephant & Castle

THEWALWORTHCOLLECTION.CO.UK ELEPHANT & CASTLE | SE17 1 / 1 THEWALWORTHCOLLECTION.CO.UK ELEPHANT & CASTLE | SE17 1 A collection of studio, one, two and three bedroom beautifully appointed apartments in London’s vibrant Elephant & Castle. The walworth collection 237 Walworth Road london SE17 ELEPHANT & CASTLE | SE17 2 / 3 your brilliant new home at the walworth collection, SE17. Welcome to The Walworth Collection, a new development of beautifully appointed apartments in London’s flourishing Elephant & Castle area. With major regeneration already well underway, this is a fantastic spot to really make the most of London life. A stone’s throw to the green spaces of Burgess Park, The Walworth Collection will comprise 59 new apartments and one luxury penthouse, providing you with a great opportunity to purchase in this up-and-coming area. The walworth collection: inspired by history, built for the future. At this time of change and with a major regeneration programme well underway, Elephant & Castle is making the most of its central London location. There are plans for new theatres and cinemas, places to eat and shop, and plenty of green open spaces. Elephant & Castle will become a revitalised town centre, a destination for visitors, as well as an outstanding neighbourhood in which to live, work and learn. The Mayor of London’s London Plan recognises Elephant & Castle as an Opportunity Area where growth can happen and should be encouraged. Computer generated image for illustrative purposes only. THEWALWORTHCOLLECTION.CO.UK ELEPHANT & CASTLE | SE17 4 / 5 Computer generated image for illustrative purposes only. “The Mayor of London’s London Plan recognises Elephant & Castle as an Opportunity Area where growth can happen and should be encouraged.” a fantastic new development at the heart of ‘the elephant.’ Over the past decade, Southwark Council, The Mayor and Greater London Authority, and Transport for London have all worked together to plan and implement improvements in Elephant & Castle. -

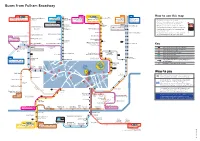

Buses from Fulham Broadway

Buses from Fulham Broadway 295 28 414 14 11 N11 Green Park towards Ladbroke Grove Sainsbury’s Shepherd’s Bush towards Kensal Rise Notting towards Maida Hill towards towards towards for Westeld from stops A, F, H Hill Gate Chippenham Road/ Russell Square Liverpool Street Liverpool Street from stops C, D, F, H Shirland Road Appold Street Appold Street from stops E, L, U, V N28 from stops E, L, U, V from stop R from stops B, E, J, R towards Camden Town Kensington Park Lane 211 Hyde Park Victoria SHEPHERD’S from stops A, F, H Church Street Corner towards High Street Waterloo BUSH Kensington Knightsbridge from stops B, E, J, L, U, V Harrods Buses from295 Fulham Broadway Victoria Coach Station Shepherd’s Bush Road KENSINGTON Brompton Road 306 HAMMERSMITH towards Acton Vale Hammersmith Library 28 N28 Victoria & Albert from stops A, F, H Museum Hammersmith Kensington 14 414 High Street 11 211 N11 295 Kings Mall 28 414 14 South Kensington 11 N11 Kensington Olympia Green Park Sloane Square towards Ladbroke GroveShopping Sainsbury’s Centre HammersmithShepherd’s Bush towards Kensal Rise Notting towards Maida Hill for Natural Historytowards and towards towards Busfor West Stationeld 306 from stops A, F, H Hill Gate Chippenham Road/ ScienceRussell Museums Square Liverpool Street Liverpool Street from stops C, D, F, H Shirland Road Appold Street Appold Street Hammersmith from stops E, L, U, V Hammersmith 211 Road N28 from stops E, L, U, V from stop R from stops B, E, J, R Town Hall from stops C, D, F, M, W towards Camden Town Park Lane 306 Kensington -

Regeneration NI Creating 21St Century Town and City Centres

Regeneration NI Creating 21st Century Town and City Centres NEW THINKING FRESH LEADERSHIP AMBITIOUS INITIATIVES 1 The wholesale change needed to revitalise our town centres and give them a fighting chance of survival will only come, however, when there is an acceptance that the old order of things is crumbling before our eyes. We still rely on old models that are not fit for the 21st century and this is holding back change.” Grimsey Review, 2018 2 3 INTRODUCTION For nearly twenty years, Retail NI and its membership have been champions for our town centres and high streets, bringing forward new ideas and policy solutions to decision-makers at all levels of government. Our members are entrepreneurs who provide an important service to their local communities and believe in real and genuine partnerships with their local Councils. They champion strong, vibrant and diverse town centres, which are in themselves, centres of both retail and hospitality excellence. We have already successfully lobbied for the introduction of the Small Business Rate Relief Scheme, the Town Centre First Planning Policy, legislation for Business Improvement schemes, five hours for £1 off-street car parking discount and much more. The theme of this report is regeneration and how to create 21st century town and city centres. With the Local Government Elections in 2019, we believe it is time to update our policy priorities and introduce some new ideas. I look forward to engaging with members, stakeholders and political representatives across Northern Ireland in the months ahead, asking for their support to initiate the process of regenerating our high streets, regenerating our workforce, regenerating our infrastructure and regenerating our political structures. -

Venue Id Venue Name Address 1 City Postcode Venue Type

Venue_id Venue_name Address_1 City Postcode Venue_type 2012292 Plough 1 Lewis Street Aberaman CF44 6PY Retail - Pub 2011877 Conway Inn 52 Cardiff Street Aberdare CF44 7DG Retail - Pub 2006783 McDonald's - 902 Aberdare Gadlys Link Road ABERDARE CF44 7NT Retail - Fast Food 2009437 Rhoswenallt Inn Werfa Aberdare CF44 0YP Retail - Pub 2011896 Wetherspoons 6 High Street Aberdare CF44 7AA Retail - Pub 2009691 Archibald Simpson 5 Castle Street Aberdeen AB11 5BQ Retail - Pub 2003453 BAA - Aberdeen Aberdeen Airport Aberdeen AB21 7DU Transport - Small Airport 2009128 Britannia Hotel Malcolm Road Aberdeen AB21 9LN Retail - Pub 2014519 First Scot Rail - Aberdeen Guild St Aberdeen AB11 6LX Transport - Local rail station 2009345 Grays Inn Greenfern Road Aberdeen AB16 5PY Retail - Pub 2011456 Liquid Bridge Place Aberdeen AB11 6HZ Retail - Pub 2012139 Lloyds No.1 (Justice Mill) Justice Mill Aberdeen AB11 6DA Retail - Pub 2007205 McDonald's - 1341 Asda Aberdeen Garthdee Road Aberdeen AB10 7BA Retail - Fast Food 2006333 McDonald's - 398 Aberdeen 1 117 Union Street ABERDEEN AB11 6BH Retail - Fast Food 2006524 McDonald's - 618 Bucksburn Inverurie Road ABERDEEN AB21 9LZ Retail - Fast Food 2006561 McDonald's - 663 Bridge Of Don Broadfold Road ABERDEEN AB23 8EE Retail - Fast Food 2010111 Menzies Farburn Terrace Aberdeen AB21 7DW Retail - Pub 2007684 Triplekirks Schoolhill Aberdeen AB12 4RR Retail - Pub 2002538 Swallow Thainstone House Hotel Inverurie Aberdeenshire AB51 5NT Hotels - 4/5 Star Hotel with full coverage 2002546 Swallow Waterside Hotel Fraserburgh -

De Beauvoir Crescent, Hoxton, N1 £650000

Islington 1 Theberton St London N1 0QY Tel: 020 7354 3283 [email protected] De Beauvoir Crescent, Hoxton, N1 £650,000 - Leasehold 2 bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms Preliminary Details A stunning two bedroom apartment situated on the third floor of a contemporary canal side development in Haggerston. This modern, bright and airy apartment features a large open plan kitchen/living room with side canal views. Shoreditch and Old Street area are one of London's most sought-after environments. Located in the heart of Tech and Architecture and amongst this creative area, you'll find fine dining, trendy bars, and upmarket boutiques. Key Features • En-suite Master Bedroom • Modern Kitchen • Floor to Ceiling Windows • Large Living Room Islington | 1 Theberton St, London, N1 0QY | Tel: 020 7354 3283 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2013 Nearest Stations Haggerston (0.2M) Hoxton (0.4M) Dalston Junction (0.7M) Islington | 1 Theberton St, London, N1 0QY | Tel: 020 7354 3283 | [email protected] 2 Floor Plan Islington | 1 Theberton St, London, N1 0QY | Tel: 020 7354 3283 | [email protected] 3 Tenure Information Lease: 140 Years Remaining Service Charge: £3,280.00 Annually Ground Rent: £350.00 Annually Energy Efficiency Rating & Environmental Impact (CO2) Rating Council Tax Bands Council Band A Band B Band C Band D Band E Band F Band G Band H Islington £ 953 £ 1,112 £ 1,271 £ 1,429 £ 1,747 £ 2,065 £ 2,382 £ 2,859 Average £ 934 £ 1,060 £ 1,246 £ 1,401 £ 1,713 £ 2,024 £ 2,335 £ 2,803 Disclaimer Every care has been taken with the preparation of these Particulars but complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. -

101 DALSTON LANE a Boutique of Nine Newly Built Apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN

101 DALSTON LANE A boutique of nine newly built apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN 101 DLSTN is a boutique collection of just 9 newly built apartments, perfectly located within the heart of London’s trendy East End. The spaces have been designed to create a selection of well- appointed homes with high quality finishes and functional living in mind. Located on the corner of Cecilia Road & Dalston Lane the apartments are extremely well connected, allowing you to discover the best that East London has to offer. This purpose built development boasts a collection of 1, 2 and 3 bed apartments all benefitting from their own private outside space. Each apartment has been meticulously planned with no detail spared, benefitting from clean contemporary aesthetics in a handsome brick external. The development is perfectly located for a work/life balance with great transport links and an endless choice of fantastic restaurants, bars, shops and green spaces to visit on your weekends. Located just a short walk from Dalston Junction, Dalston Kingsland & Hackney Downs stations there are also fantastic bus and cycle routes to reach Shoreditch and further afield. The beautiful green spaces of London Fields and Hackney Downs are all within walking distance from the development as well as weekend attractions such as Broadway Market, Columbia Road Market and Victoria Park. • 10 year building warranty • 250 year leases • Registered with Help to Buy • Boutique development • Private outside space • Underfloor heating APARTMENT SPECIFICATIONS KITCHEN COMMON AREAS -

YPG2EL Newspaper

THE YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO EAST LONDON East London places they don’t put in travel guides! Recipient of a Media Trust Community Voices award A BIG THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS This organisation has been awarded a Transformers grant, funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor and managed by ELBA Café Verde @ Riverside > The Mosaic, 45 Narrow Street, Limehouse, London E14 8DN > Fresh food, authentic Italian menu, nice surroundings – a good place to hang out, sit with an ice cream and watch the fountain. For the full review and travel information go to page 5. great places to visit in East London reviewed by the EY ETCH FO P UN K D C A JA T I E O H N Discover T B 9 teenagers who live there. In this guide you’ll find reviews, A C 9 K 9 1 I N E G C N YO I U E S travel information and photos of over 200 places to visit, NG PEOPL all within the five London 2012 Olympic boroughs. WWW.YPG2EL.ORG Young Persons Guide to East London 3 About the Project How to use the guide ind an East London that won’t be All sites are listed A-Z order. Each place entry in the travel guides. This guide begins with the areas of interest to which it F will take you to the places most relates: visited by East London teenagers, whether Arts and Culture, Beckton District Park South to eat, shop, play or just hang out. Hanging Out, Parks, clubs, sport, arts and music Great Views, venues, mosques, temples and churches, Sport, Let’s youth centres, markets, places of history Shop, Transport, and heritage are all here. -

Hackney Markets Strategy 2015-20 Contents

Hackney Markets Strategy 2015-20 Contents FOREWORD FROM THE CABINET MEMBER FOR NEIGHBOURHOODS .......................................... 3 CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2. WHY WE NEED A MARKET STRATEGY ........................................................................................... 5 1.3. STRUCTURE OF THE STRATEGY ..................................................................................................... 7 1.3.1 MARKETS STRATEGY DOCUMENTS ......................................................................................................... 7 1.4. CONTEXT ............................................................................................................................................... 9 1.4.1 NATIONAL & REGIONAL CONTEXT ........................................................................................................... 9 1.4.2 LONDON AND GREATER LONDON . ......................................................................................................... 10 1.5. HACKNEY DEMOGRAPHICS ............................................................................................................ 11 1.5.1 THE POPULATION .................................................................................................................................. -

Older Generations to Rescue the High Street

Older generations to rescue the high street Sponsored by Perspectives centreforfuturestudies strategic futures consultancy The Centre for Future Studies (CFS) is a strategic futures consultancy enabling organisations to anticipate and manage change in their external environment. Our foresight work involves research and analysis across the spectrum of political, economic, social and technological themes. Our clients include national and international companies, not-for-profit organisations, government departments and agencies. Centre for Future Studies Innovation Centre Kent University Canterbury, Kent CT2 7FG +44 (0) 800 881 5279 [email protected] www.futurestudies.co.uk November 2017 ________________________________________________________________ 2 centreforfuturestudies strategic futures consultancy Acknowledgements This report builds on the findings of the work undertaken by the International Longevity Centre – UK (ILC-UK); in particular: . “The Missing £Billions: The economic cost of failing to adapt our high street to respond to demographic change.” December 2016. “Understanding Retirement Journeys: Expectations vs reality.” November 2015. Future of ageing conference. November 2015 . “Financial Wellbeing in Later Life. Evidence and policy. March 2014 Key data sources: Age UK British Independent Retailers Association British Retail Consortium Communities & Local Government Centre for Retail Research Council of Shopping Centres Department for Business Innovation & Skills Department for Communities & Local Government Friends of the Elderly Innovate UK Institute for Public Policy Research Ipsos Retail Performance Kings Fund KPMG NatCen - the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (2014/15) Office for National Statistics The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), The UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS, now known as Understanding Society) UK Data Service World Health Organisation ________________________________________________________________ 3 centreforfuturestudies strategic futures consultancy Contents 1. -

The State of Scotland's High Streets

Charity Retail Association’s Scottish seminar 2015 The State of Scotland’s High Streets David Lonsdale, Director, SRC Scottish Retail Consortium: . Established in April 1999 . 255 brands in membership include well-known high street and online retailers, plus grocers and trade associations . Policy & market intelligence; representation; networking . Champions the retail industry and campaigns for a competitive policy landscape. Positions are determined by 16-strong SRC Board after consultation with wider membership . 4 C’s: competitiveness, careers, communities, constitution . Topical issues: devolved budget, NDR, carrier bags, high streets, regulation, building standards, devolution Represent 255 brands including: Sector size and importance • 257,000 employees • Largest private sector employer • 23,000 shops • 9% of businesses are retailers • Retailers invest £1,400 p.a. in training each employee • Retail pays quarter of all NDR • In independent research the public rated high street retailers & supermarkets as top sectors for community engagement S % change y-o-y RC - - - - - KPMG Scottish 0.0 2.0 4.0 6.0 8.0 8.0 6.0 4.0 2.0 Jan-13 Apr-13 Jul-13 Oct-13 Retail Monitor Sales Jan-14 Apr-14 Jul-14 Oct-14 Jan-15 Source: SRC/KPMG Source: Non Sales All Food - food SRC- Springboard Footfall and Vacancies Monitor Source: SRC/Springboard 10.0% 12.0% 13.0% SRC 11.0% 8.0% 9.0% - Jul-11 Vacancies and MonitorSpringboard Footfall Oct-11 Jan-12 Apr-12 Jul-12 Rate Vacancy UK Oct-12 Jan-13 Scotland Apr-13 Jul-13 Oct-13 SRC/Springboard Source: Jan-14 Apr-14 Jul-14 Oct-14 Jan-15 Town centres - main drivers of change (“shift in power from retailer to consumer”): • Structural e.g. -

Re-Imagining the High Street Escape from Clone Town Britain

Re-imagining the high street Escape from Clone Town Britain The 2010 Clone Town Report nef is an independent think-and-do tank that inspires and demonstrates real economic well-being. We aim to improve quality of life by promoting innovative solutions that challenge mainstream thinking on economic, environmental and social issues. We work in partnership and put people and the planet first. A report from the Connected Economies Team nef (the new economics foundation) is a registered charity founded in 1986 by the leaders of The Other Economic Summit (TOES), which forced issues such as international debt onto the agenda of the G8 summit meetings. It has taken a lead in helping establish new coalitions and organisations such as the Jubilee 2000 debt campaign; the Ethical Trading Initiative; the UK Social Investment Forum; and new ways to measure social and economic well-being. Contents Foreword 2 Executive summary 3 Part 1: High street collapse? 6 Part 2: The clone town parade 2009 13 Part 3: Communities fighting back 27 Part 4: Re-imagining your local high street to support a low carbon, high well-being future 34 Recommendations 43 Appendix: Clone Town Survey 44 Endnotes 46 Foreword Why does it matter that our town centres increasingly all look the same? Is the spread of clone towns and the creeping homogenisation of the high street anything more than an aesthetic blight? We think so. Yes, distinctiveness and a sense of place matter to people. Without character in our urban centres, living history and visible proof that we can in some way shape and influence our living environment we become alienated in the very places that we should feel at home.