Mediterranean City-To-City Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE The Central Park in between Torino and Milano Original The Central Park in between Torino and Milano / Andrea, Rolando; Alessandro, Scandiffio. - STAMPA. - (2016), pp. 336- 336. ((Intervento presentato al convegno TASTING THE LANDSCAPE - 53rd IFLA WORLD CONGRESS tenutosi a TORINO nel 20-21-22 APRILE 2016. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2645620 since: 2016-07-26T10:24:06Z Publisher: Edifir-Edizioni Firenze Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 04 August 2020 TASTING THE LANDSCAPE 53rd IFLA WORLD CONGRESS APRIL • 20th 21st 22rd • 2016 TORINO • ITALY © 2016 Edifir-Edizioni Firenze via Fiume, 8 – 50123 Firenze Tel. 055/289639 – Fax 055/289478 www.edifir.it – [email protected] Managing editor Simone Gismondi Design and production editor Silvia Frassi ISBN 978-88-7970-781-7 Cover © Gianni Brunacci Fotocopie per uso personale del lettore possono essere effettuate nei limiti del 15% di ciascun volume/fascicolo di periodico dietro pagamento alla SIAE del compenso previsto dall ’ art. 68, comma 4, della legge 22 aprile 1941 n. 633 ovvero dall ’ accordo stipulato tra SIAE, AIE, SNS e CNA, CONFARTIGIANATO, CASA, CLAAI, CON- FCOMMERCIO, CONFESERCENTI il 18 dicembre 2000. Le riproduzioni per uso differente da quello personale sopracitato potranno avvenire solo a seguito di specifica autorizzazione -

Visite Guidate

Visite Guidate urismo Torino e Turismo Torino e Provincia proposes guided walking tours in the historical town centre Cultural guided tours Provincia propone of Ivrea: the theme is Water, a fundamental visite guidate a piedi T resource for the town’s history. The tours are in nel centro storico di Ivrea: Italian/English and last two hours. tema conduttore l’Acqua, risorsa fondamentale per la storia della città. I tour, in italiano/inglese, durano due ore. Dove e quando | Where and when Mar|Tue 3 giu|June, h 10 & 14 partenza dallo IAT di Ivrea in corso Vercelli 1 | departing from the IAT of Ivrea in corso Vercelli 1 Gio|Thu 5 - ven|Frid 6 giu|June, h 10 Sab|Sat 7 giu|June, h 16 41 partenza dallo Stadio della Canoa | departing from the Stadio della Canoa Itinerario | Itinerary Corso Massimo d’Azeglio - via Palestro - via Cattedrale - piazza Castello - via Quattro Martiri - via Arduino - piazza Vittorio Emanuele - Lungo Dora - Torre di Santo Stefano Stadio della Canoa - corso Nigra - Lungo Dora - Torre di Santo Stefano - via Palestro - via Cattedrale - piazza Castello - via Quattro Martiri - via Arduino - piazza Vittorio Emanuele Per informazioni & prenotazioni | For information & bookings: TIC Ivrea: corso Vercelli 1 – tel. +39-0125618131 – [email protected] Aperto tutti i giorni|open every day h 9-12.30 and 14.30-19 Stand Turismo Torino e Provincia: Stadio della Canoa, 5/8 giu|June, h 10-18 AOSTA MONTE BIANCO GRAN SAN BERNARDO Oropa PPoont-nt- Il nostro territorio. Saint-Martin Carema 2371 2756 A5 Colma di Mombarone Pianprato Sordevolo Campiglia Mte Marzo Quincinetto Pta Tressi Soana BIELLA 2865 Settimo Graglia Our land. -

Torino City Story

Torino City Story CASEreport 106: May 2016 Anne Power Contents Figures ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Boxes ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 About LSE Housing and Communities ........................................................................................................ 4 Foreword and acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2. History in brief ........................................................................................................................................ 7 3. The first industrial revolution and the birth of Fiat ................................................................................ 9 4. World War Two ....................................................................................................................................11 Post-war recovery .....................................................................................................................................11 5. Industrial and social strife ....................................................................................................................14 -

The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando

Vincentiana Volume 47 Number 2 Vol. 47, No. 2 Article 5 3-2003 The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando Luigi Chierotti C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Chierotti, Luigi C.M. (2003) "The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando," Vincentiana: Vol. 47 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol47/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando by Luigi Chierotti, C.M. Province of Turin Fr. Durando never wrote a book, nor published one, except for an “educative” pamphlet, written for an Institute of the Daughters of Charity at Fontanetta Po. His collection of letters, however, is a veritable “monument,” and a mine of information on civil and religious life, on the spiritual direction of persons, of the dispositions of governance for the works, etc., from 1831-1880. Today his correspondence is collected in eight large volumes, typewritten, and photocopied, with an accompanying analytical index. I spent a long time working like a Carthusian, in order to transcribe the texts of the “original” letters, the notes, and the reports. -

Dynamics of Supply Chain Agreements for Development of Biomass Plants

Dynamics of Supply Chain Agreements for Development of Biomass Plants “Rubires” and the Cogeneration Station of Carmagnola This operation is implemented through the CENTRAL EUROPE Programme co-financed by the ERDF The document hereby has been edited on completion of the pilot activity of the “Rural Biological Resources” (RUBIRES) Project, co-funded by the 2007-2013 Central Europe Programme within the “European territorial Cooperation” strategy. Project Partner: Società Consortile a r.l. [Consortium LLC]Langhe Monferrato Roero (LAMORO) Local Development Agency Via Leopardi, 4 - 14100 Asti Tel. + 39 0141 532516 Fax + 39 0141 532228 www.lamoro.it E-mail: [email protected] By: Dr. GIUSEPPE TRESSO CLIPPER S.r.l. Mob. + 39 348 8006080 E-mail: [email protected] November 2011 2 Contents: 1 Rubires and the Project of the Cogeneration Station of Carmagnola ....................................................... 4 1.1 Preliminary Remarks .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 The Supply Chain Agreement for the Project of Carmagnola ........................................................... 5 2 The Supply Chain Agreements in the Biomass Sector ........................ Errore. Il segnalibro non è definito. 2.1 What does “Supply Chain Agreement” Mean? .......................... Errore. Il segnalibro non è definito. 2.1.1 Analysis of the Territory Potential ........................................................................................... 10 2.1.2 Choice -

The Alpine Population of Argentera Valley, Sauze Di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: Vestiges of an Occitan Culture and Anthropo-Ecology R

This article was downloaded by: [Renata Freccero] On: 27 April 2015, At: 12:28 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Global Bioethics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: Click for updates http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rgbe20 The Alpine population of Argentera Valley, Sauze di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: vestiges of an Occitan culture and anthropo-ecology R. Frecceroa a Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy Published online: 27 Apr 2015. To cite this article: R. Freccero (2015): The Alpine population of Argentera Valley, Sauze di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: vestiges of an Occitan culture and anthropo-ecology, Global Bioethics, DOI: 10.1080/11287462.2015.1034473 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/11287462.2015.1034473 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

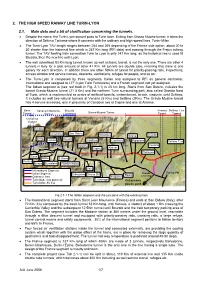

2. the HIGH SPEED RAIWAY LINE TURIN-LYON 2.1. Main Data and a Bit of Clarification Concerning the Tunnels

2. THE HIGH SPEED RAIWAY LINE TURIN-LYON 2.1. Main data and a bit of clarification concerning the tunnels. • Despite the name, the Turin-Lyon doesn’t pass to Turin town. Exiting from Gravio Musine tunnel, it takes the direction of Settimo Torinese where it connects with the ordinary and high-speed lines, Turin–Milan. • The Turin-Lyon TAV length ranges between 254 and 265 depending of the France side option, about 20 to 30 shorter than the historical line which is 287 Km long (RFI data) and passing through the Frejus railway tunnel. The TAV fleeting train connection Turin to Lyon is only 247 Km long, as the historical line is used till Bruzolo, then the new line until Lyon. • The well advertised 53 Km long tunnel, known as well as basic tunnel, is not the only one. There are other 4 tunnels in Italy for a total amount of other 41 Km. All tunnels are double tube, meaning that there is one gallery for each direction. In addition there are other 50Km of tunnel for priority-passing rails, inspections, access window and service tunnels, descents, ventilations, refuges for people, and so on. • The Turin-Lyon is composed by three segments, Italian and assigned to RFI as general contractor, International and assigned to LTF (Lyon Turin Ferroviaire) and a French segment, not yet assigned. The Italian segment is (see red track in Fig. 2.1-1) is 43 km long. Starts from San Didero, includes the tunnel Gravio-Musine tunnel (21.3 Km) and the northern Turin surrounding part, also called Gronda Nord of Turin, which is implemented as series of artificial tunnels, embankment, trench, viaducts, until Settimo. -

A Brief History of Turin-Lyon High-Speed Railway 2

1 Paola Manfredi, Cristina Massarente, Franck Violet, Michel Cannarsa, Caterina Mazza and Valeria Ferraris A BRIEF HISTORY OF TURIN-LYON HIGH-SPEED RAILWAY 2 Paola Manfredi, Cristina Massarente, Franck Violet, Michel Cannarsa, Caterina Mazza and Valeria Ferraris1 A brief history of Turin-Lyon high-speed railway Table of Content 1. Introduction 2. The origin of the project and the stakeholders involved 3. The history of the project 4. Criminal infiltration and high-speed railway in the media 5. References 1. Introduction The history of the project of the New Railway Line Turin-Lyon, shortened as NLTL and currently known as high-speed train Turin- Lyon (named TAV Turin-Lyon), saw a lot of stakeholders that interacted, exchanged, conflicted and overlapped. The first part of this paper aims at understanding the evolution/origin of the project in order to clarify the role of the Italian and French stakeholders involved. Then, the paper continues with the description of the main steps of the history of TAV project. In these steps will be underlined the moments in which some stakeholders have been involved in incidents of lawlessness and corruption. 2. The origin of the project and stakeholders involved 2.1 The Italian stakeholders The project for the TAV Turin-Lyon involved many Italian stakeholders, institutional and not. First of all in 1989 the Associazione Tecnocity2 presented in a public meeting at the Fondazione Agnelli the project of a high-speed railway line for passengers between France and Italy. The project foresees the construction of a transalpine tunnel 50 km long as a part of the future railway line between East and West Europe (Number Five Corridor3). -

A Glance at Our

AIR QUALITY MONITORING NETWORK AA glanceglance atat ourour airair The air quality monitoring network operating in the province of Turin is managed by Arpa Piemonte. It is composed of 23 monitoring stations (16 background stations and 7 traffic stations) and one mobile station for short measuring Annual report on data collected by campaigns. All the stations are connected to the data acquisition centre provincial air quality monitoring network by telephone lines and transmit hourly measurement result. provincial air quality monitoring network This setup allows a continuous monitoring of the main factors that may affect air quality. Location of measurement stations on the territory is a key factor to achieve a cost-effective air quality monitoring. In Sergio Dall’Olio, above sky 2014 Torino some cases the selected sites must be representative of a large portion of territory, in other cases stations must 20142014 previewpreview represent specific pollution situation like traffic hot spot or single source emissions. A strategic location of measurement points gives extremely representative information on air quality. MEASUREMENT STATIONS AIR QUALITY IN THE PROVINCE OF TURIN Station Address Pollutants Type of station Data collected during the last 10 years by air quality monitoring network Pollutant Situation Baldissero (GDF) (1) Str. Pino Torinese, 1 – Baldissero NO , O , CO, PM10ß, PAHs deposimeter Rural background operating in the province of Turin and managed by Arpa Piemonte show an x 3 sulphur dioxide Beinasco Via S. Pellico, 5 – Beinasco NO x Urban background overall and significant improvement but at the same time confirm the critical NO PM10 , PM10 ß , PM2,5 ß, BTX, PCDD/DF sampling situation of the territory, in particular of the Turin urban area. -

09HON9 1 Sortie Piemont.Indd

F Xperience Ride Piémont Xperience Ride Piemont Xperience Ride Piémont Voyage 1 Voyage 2 Pilotes de CBF600/1000 et Deauville: plein gaz sur le Piémont Pilotes de Transalp et Varadero: randonnée au Piémont du 2 au 6 septembre 2009 du 26 au 30 août 2009 Enfourchez votre CBF ou Deauville pour découvrir, accompagné d’un guide expérimenté, les Enfourchez votre Transalp ou Varadero pour découvrir, accompagné d’un guide chevronné, charmes de la route qui vous emmènera dans la magnifi que région du Piémont ! les charmes de la route qui vous emmènera dans la magnifi que région du Piémont ! 1ère étape : 1ère étape: Rendez-vous à 7h à l’Hôtel du Vieux Stand de Martigny. Départ destination le col du Rendez-vous à 7h à l’Hôtel du Vieux Stand de Martigny. Départ destination le col du Grand-Saint-Bernard, celui d’Iseran, du Mont-Cenis ainsi que la vallée de Susa, avec Grand-Saint-Bernard, celui d’Iseran, du Mont-Cenis ainsi que la vallée de Susa, avec arrivée à Cesana Torinese pour le repas du soir et la première nuit. arrivée à Cesana Torinese pour le repas du soir et la première nuit. En cas d’enneigement des cols, l’itinéraire est le suivant : Turin par l’autoroute, Pinerolo En cas d’enneigement des cols, l’itinéraire est le suivant : Turin par l’autoroute, Pinerolo et Cesana Torinese et Cesana Torinese. 2ème étape: 2ème étape: Grasse matinée avant une escapade en bus pour Clavière à 10h, suivie de 45 minutes Excursion pour une dégustation de polenta dans les Alpes. -

Verso Una Città Metropolitana Del Cibo

Urban&Rural Cooperation: the Metropolitan City of Torino’s projects The Metropolitan Food Agenda The front office for new mountain and rural inhabitants («Living and Working in mountain areas») Working Group Metropolitan Areas Meeting – Eurocities – 18th of june 2021 For Torino Food policy is a new dimension “Food security (is ) a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have phisical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healty life” (Amartya Sen, Nobel on Economy) To feed “Resilient” Cities/Metropolis From agricultural, environmental, market, urban planning, health policies to Food policies From Government to Governance (focus of dynamic relationships between actors: producers, consumers, trade, civil society/stakeholders/lobbies, public authorities) Why we are dealing with Food Policies? Because Food is a primary need of human being (the third one after air and water) essential for Life Because the “access” to food is not only a question of quantity but of quality, not solved even in “rich and developped” countries (obesity/overweigth, diabetes, 50% of diseases linked to the food diet and style, increasing poor people) Because it is an hidden cost for the Public Health budgets Because Public Authorities have a Moral Responsibility to their citizens’ LIFE Because, last but not least, IT IS A QUESTION OF FOOD DEMOCRACY and food justice, THEN A QUESTION OF DEMOCRACY How we reached the Food approach: wich food policy -

The Stellantis Heritage Department and Leasys, Sponsors and Partners of the 39Th Cesana- Sestriere

THE STELLANTIS HERITAGE DEPARTMENT AND LEASYS, SPONSORS AND PARTNERS OF THE 39TH CESANA- SESTRIERE ● Sunday, July 11th will witness the running of the 39th edition of the Cesana-Sestriere, one of the biggest international historic sportscar racing events, forming part of the European and Italian vintage car speed championships. ● Over 120 drivers will stake their claim on the spectacular 10.4-km track, rising from 1,300 m above sea level at Cesana Torinese to 2,035 m at Sestriere, both renowned mountain resorts. ● The race Sponsor is the Stellantis Heritage department, which will also feature in the Cesana-Sestriere Experience parade, with a rare model of the 1951 Lancia Aurelia B20, owned by the department itself. ● Leasys, the event partner, will take part in the Cesana-Sestriere Experience with two New Fiat 500 models from its LeasysGO! car sharing fleet, one at the start and another at the end of the parades on Saturday and Sunday mornings. ● Stellantis and Leasys will also provide and put on display an extensive fleet of service cars consisting of the latest models from the Abarth, Alfa Romeo and Fiat brands, up to the most recent full-electric New 500 from the LeasysGO! car sharing scheme. Turin, July 9th 2021 In the morning of Sunday, July 11th, following technical checks and official qualifiers the two days before, taking to the road will be the 39th edition of the Cesana-Sestriere, a time trial for vintage cars organized by the Automobile Club Torino. The “CE-SE” – as it is known in the racing world – began in 1961 to celebrate the centenary of Italian unification, and has gradually become one of the main international competitions in historic sportscar racing, forming part of the European and Italian vintage car speed championships.