The Rhetoric of Drugs. an Interview the Following Interview Originally Appeared in a Special Issue of Autrement 106 (1989) Edited by J.-M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Little Terrors'

Don DeLillo’s Promiscuous Fictions: The Adulterous Triangle of Sex, Space, and Language Diana Marie Jenkins A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of English University of NSW, December 2005 This thesis is dedicated to the loving memory of a wonderful grandfather, and a beautiful niece. I wish they were here to see me finish what both saw me start. Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One 26 The Space of the Hotel/Motel Room Chapter Two 81 Described Space and Sexual Transgression Chapter Three 124 The Reciprocal Space of the Journey and the Image Chapter Four 171 The Space of the Secret Conclusion 232 Reference List 238 Abstract This thesis takes up J. G. Ballard’s contention, that ‘the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else,’ to show that Don DeLillo uses a particular sexual, cultural economy of adultery, understood in its many loaded cultural and literary contexts, as a model for semantic reproduction. I contend that DeLillo’s fiction evinces a promiscuous model of language that structurally reflects the myth of the adulterous triangle. The thesis makes a significant intervention into DeLillo scholarship by challenging Paul Maltby’s suggestion that DeLillo’s linguistic model is Romantic and pure. My analysis of the narrative operations of adultery in his work reveals the alternative promiscuous model. I discuss ten DeLillo novels and one play – Americana, Players, The Names, White Noise, Libra, Mao II, Underworld, the play Valparaiso, The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, and the pseudonymous Amazons – that feature adultery narratives. -

"One Nation •¦ Indivisible": Jacques Derrida on the Autoimmunity

RP 36_f4_12-44 11/13/06 11:56 AM Page 15 “ONE NATION . INDIVISIBLE”: JACQUES DERRIDA ON THE AUTOIMMUNITY OF DEMOCRACY AND THE SOVEREIGNTY OF GOD by MICHAEL NAAS DePaul University ABSTRACT During the final decade of his life, Jacques Derrida came to use the trope of autoimmunity with greater and greater frequency. Indeed it today appears that autoimmunity was to have been the last iteration of what for more than forty years Derrida called decon- struction. This essay looks at the consequences of this terminological shift for our under- standing not only of Derrida’s final works (such as Rogues) but of his entire corpus. By taking up a term from the biological sciences that describes the process by which an organism turns in quasi-suicidal fashion against its own self-protection, Derrida was able to rethink the very notion of life otherwise and demonstrate the way in which every sovereign identity, from the self to the nation-state to, most provocatively, God, is open to a process that both threatens to destroy it and gives it its only chance of living on. 1. Pledge of Allegiance I In a volume of remembrance, a volume “in memory of Jacques Derrida,” it is perhaps not inappropriate to begin with a personal memory, even if it might initially appear to have little to do with Derrida.1 It is an old memory, a quintessentially American memory, and one that I suspect many readers of this journal may share. It is the memory of a speech act, a sort of originary profession of faith, the memory of a pledge that I, like most other American school children, recited by heart, that is, in my case, thoughtlessly, mechani- cally, irresponsibly, with the regularity of a tape recording played back in an endless loop, at the beginning of every single school day. -

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM Title: The rhetoric of drugs: an interview Author(s): Michael Israel Source: differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 5.1 (Spring 1993): p1. Document Type: Interview Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1993 Duke University Press http://dukeupress.edu/ Full Text: Works Cited Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Trans. John Cumming. London: Verso, 1979. Artaud, Antonin. "Letter to the Legislator of the Drug Act." Collected Works of Antonin Artaud. Trans. Victor Conti. Vol. 1. London: Calder, 1968. 58-62. 4 vols. 1968-74. Baudelaire, Charles. "Les Paradis artificiels." Oeuvres completes. Ed. Claude Pichois. Vol. 2. Paris: Gallimard, 1975. The following interview originally appeared in a special issue of Autrement 106 (1989) edited by J.-M. Hervieu and then in the collection, Points de suspension: Entretiens (Paris: Galilee, 1992). Michael Israel's translation was first published in 1-800 2 (1991). Eds. When the sky of transcendence comes to be emptied, a fatal rhetoric fills the void, and this is the fetishism of drug addiction. A: You are not a specialist in the study of drug addiction, yet we suppose that as a philosopher you may have something of particular interest to say on this subject. At the very least, we assume that your thinking might be pertinent here, if only by way of those concepts common both to philosophy and addictive studies, for example dependency, liberty, pleasure, jouissance. JD: O.K. Let us speak then from the point of view of the non-specialist which indeed I am. -

The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones Professional Writing Spring 4-24-2019 The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Morgan, "The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder" (2019). Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones. 48. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd/48 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Professional Writing at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder By Morgan Carter A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Writing in the Department of English In the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia 2019 Contents Introduction 1 Literature Review 4 Chapter One: Narrative 15 Chapter Two: Critique 30 Chapter Three: Conclusion 45 Works Cited 49 iii For those who are still sick and suffering and for the kids caught in the cross-fire Introduction The addict and alcoholic are members of society who are continuously marginalized by the language used to describe them, both by media coverage and everyday language. The nature of their disease creates a space of self-identification that is outside the norm of normal illness. -

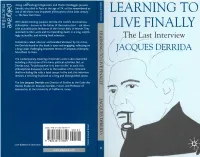

Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally the Last Interview

ZJ ~T~} 'Along with Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, Jacques Q, Qj Derrida, who died in Paris at the age of 74, will be remembered as —— one of the three most important philosophers of the 20th century.' LEARNING TO >*J — The New York Times r— ^-» With death looming, Jacques Derrida, the world's most famous __ *T\ philosopher - known as the father of 'deconstruction' - sat down ~' with journalist Jean Birnbaum of the French daily Le Monde. They LIVE FINALLY revisited his life's work and his impending death in a long, surpris• ingly accessible, and moving final interview. The Last Interview Sometimes called 'obscure' and branded 'abstruse' by his critics, the Derrida found in this book is open and engaging, reflecting on a long career challenging important tenets of European philosophy 'ACOUES DERRIDA from Plato to Marx. The contemporary meaning of Derrida's work is also examined, including a discussion of his many political activities. But, as Derrida says, 'To philosophize is to learn to die'; as such, this philosophical discussion turns to the realities of his imminent death-including life with a fatal cancer. In the end, this interview remains a touching final look at a long and distinguished career. The late Jacques Derrida was Director of Studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, France, and Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine. ISBN 978-0-230-53785-9 9 780230 537859 Cover illustration © Carol Hayes Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally The Last Interview Jacques Derrida An Interview with Jean Birnbaum Translated by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas With a bibliography by Peter Krapp All rights reserved. -

Jacques Derrida PDF Book

JACQUES DERRIDA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Royle | 208 pages | 01 Jun 2003 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415229319 | English | London, United Kingdom Jacques Derrida PDF Book Derrida argues that intention cannot possibly govern how an iteration signifies, once it becomes hearable or readable. This danger explains why unconditional openness of the borders is not the best as opposed to what we were calling the worst above ; it is only the less bad or less evil, the less violence. Jacques Derrida. Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. The event that projected him into the international limelight was a conference at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in , where the relatively unknown but incontrovertibly glamorous young philosopher upstaged the likes of Lacan and Jean Hyppolite. Derrida insisted that a distinct political undertone had pervaded his texts from the very beginning of his career. Yet each of these concepts excludes the other. And this is what I confide in secret to whomever allies himself to me. For example, an image needs to be held by something, just as a mirror will hold a reflection. The giver cannot even recognise that they are giving, for that would be to reabsorb their gift to the other person as some kind of testimony to the worth of the self — ie. The intimacy of friendship, Derrida writes, lies in the sensation of recognizing oneself in the eyes of another. I deployed all my resources to uncover a range of meanings fanning out from each sentence, each word. These are, of course, themes reflected upon at length by Derrida, and they have an immediate consequence on the meta-theoretical level. -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Endless Happiness: Confessions of a Recovering Addict Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2hh037r6 Author McCracken, Lucas Miles Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Endless Happiness: Confessions of a Recovering Addict A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Religious Studies by Lucas Miles McCracken Committee in charge: Professor Thomas Carlson, Chair Professor Andrew Norris Professor Joseph Blankholm March 2021 The thesis of Lucas Miles McCracken is approved. Joseph Blankholm ______________________________ Andrew Norris ______________________________ Thomas Carlson ______________________________ January 2021 ABSTRACT Endless Happiness: Confessions of a Recovering Addict by Lucas Miles McCracken I set out to write about how to be happy, and my questions about happiness led me to a consideration of addiction because I began to notice a fundamental similarity: Like addicts, we mortals suffer a dependence on finite substances for our joy, and their passing away always brings a comedown. To think through the implications of this parallel, I went to Augustine's Confessions—one of the most poignant and impactful reflections on the relationship between finitude and happiness in the Western philosophical tradition. My original research question, "What does it mean for a human to be happy?" transformed through my readings of Augustine into: If being human is, as we say, a "condition" then what are its symptoms, and, furthermore, what would it mean to recover from it? I analyze Augustine's own attempt to come to terms with the fact that, for us mortals, being happy means having something to lose. -

The Place of Consignation, Or Memory and Writing in Derrida's Archive

54 / JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND AESTHETICS / 55 Works Cited Beauvoir, Simone de (1989). The Second Sex, translated by H. M. Parshley. New York: Vintage Books. – (1978). The Ethics of Ambiguity, translated by Bernard Frechtman. New York: Citadel Press. Camus, Albert (1991a).The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, translated by Justin The Place of Consignation, or O’Brien. New York: Vintage International. – (1991b).The Rebel, translated by Anthony Bower. New York: Vintage International. Memory and Writing in – (1991c). The Plague, translated by Stuart Gilbert. New York: Vintage International. – (1989). The Stranger, translated by Matthew Ward. New York: Vintage International. Heidegger, Martin (2010). Being and Time, translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany: Derrida’s Archive SUNY Press. Kant, Immanuel (1996). Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, translated by Victor Lyle Dowdell. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP. Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (2002). Phenomenology of Perception, translated by Colin Smith. Aakash M. Suchak New York: Routledge Classics. Naipaul, V. S. (2002). Half a Life. New York: Vintage International. – (2001). A House for Mr. Biswas. New York: Vintage International. ore than a theoretical account of the figure and concept of the archive Sappho (2003). , translated by Anne Carson. M If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho in general, Derrida’s Archive Fever (1995) closely reads Yosef Hayim New York: Vintage Books. Sartre, Jean-Paul (1995). Being and Nothingness, translated by Hazel E. Barnes. New Yerushalmi’s “Monologue with Freud” chapter in the scholar’s Freud’s Moses: York: Gramercy Books. Judaism Terminable and Interminable (1991). To the unacquainted, this is the missing third term, between Archive Fever and the relevant texts of the Freudian corpus.1 The triangulation rests on the Moses of Michelangelo, which in turnrests on the Moses of the Old Testament. -

“War on Drugs” and “Mass Murder” in the Philippines: Discourse Analysis, Power Relations, and an Interview with President Rodrigo Duterte1 Gabriel Gama De O

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro Instituto de Relações Internacionais The Metaphor of “War on Drugs” and “Mass Murder” in the Philippines: discourse analysis, power relations, and an interview with President Rodrigo Duterte1 Gabriel Gama de O. Brasilino* Abstract In this article I offer an analysis of statements pronounced by Rodrigo Duterte in a interview conducted by two journalists from the Al Jazeera Global Media Network. I show how through these statements and rhetoric - a political discourse dependent on and effective through the metaphor of "war on drugs" - Duterte attempted to legitimize the extrajudicial killing of more than 3.500 citizens constructed as threats to public security, and enemies to be (“legitimately”) killed. I draw on Foucault's Critical and Genealogical Discourse Analysis (1971; 2003; 2007), to argue that, although the "war on drugs" is a metaphor (MIDDLEMASS, 2014) - and not war in the literal or modern sense - mobilized within a discursive strategy previous to, during and after presidential elections, it [the “war on drugs”] is a (bio)politics of drugs and security that results in confrontations, hunting, punishment, and, in the limit, extermination of declared enemies (FOUCAULT, 2003; 2007; ZACCONE, 2015). In other words, through the metaphorical language of ‘war’, President Duterte admits, tries to legitimize and normalize exceptional (political) violence(s) to deal with the “the problem of drugs,” crimes and (in)security, that is, his discourse produces specific power- and knowledge-effects. Before analyzing the statements, I delineate the historical level of Duterte’s election campaign, and the context of the interview. In the closing remarks, I consider the role of discourse analysis for critical security studies, being reflexive to the previous arguments, and offering paths for future research on the debate on drugs (de)criminalization, (racist) criminal justice systems, and political violence(s) more generally. -

Antigone Figures: Performativity and Rhythm in the Graphics of the Text

Antigone Figures: Performativity and Rhythm in the Graphics of the Text A Commentary on Texts by Carol Jacobs, Martin Heidegger, and Jacques Derrida by Melanie Lewis A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Religion University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Melanie Lewis For Dawne McCance Cynthia West Fritz West and Paul Johnson ii Abstract This thesis contributes to critical theoretical interpretation of Sophocles‟ Antigone. Analyzing texts by Kelly Oliver, Jacques Lacan, and Judith Butler, the thesis demonstrates how the work of these writers re-installs oppositional binarism, the form of thought that undergirds the hierarchical structure of Western metaphysics as exemplified in the dialectical philosophy of G. W. F. Hegel. Focusing on texts by Carol Jacobs, Martin Heidegger, and Jacques Derrida, the thesis analyzes the performative effect of Antigone, as sister figure, in the graphics of these works. Employing a deconstructive critical approach, the thesis explores the theoretical productivity of the analysis of a “sororal” graphics that, dispersing and subverting binarism, opens the texts and their interpretation to alterity. The thesis argues that critical reading of the performativity of Antigone as sister figure implicates ethicological discussions on justice in relation to family, genre/gender, classification, and inheritance. iii Acknowledgements I offer my sincere thanks, for their astute and stimulating questions and remarks, and for their timely advice and encouragement, to the members of my advisory committee, Dawne McCance, Mark Libin, and Heidi Marx-Wolf, and to the external examiner of the thesis, Lorraine Markotic. -

AUTOMATON," Infour Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis', Pierre Bayard, How to Talk About Books You Haven't Read', Géra

ENG 6075Deconstruction and New Media Theory Fall 2013 R, Periods 3-5 Professor Richard Burt Course Description: This will survey some of the central text written by Jacques Derrida, particularly those that bear on new media. The premise of this course is that books are random access machines that both resist and seduce their readers. As we read Derrida's texts, we will also read book history, focusing on the ways in which distinction between scroll and codex is reworked in new media (scrolling functions, keyboards, pdfs). That history will be under constant philosophical pressure about what a book is, what a machine is, what it means to read and to reconstitute a reading, the fate or the chances of reading, and what Derrida “calls “unreadability.” We will consider the book on paper and online as a more or less resistant random access machine. Readings will include Jacques Derrida, Paper Machine', "Typewriter Ribbon. Ink (2)" in Without Alibi', Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever, Jacques Derrida"Meschances"; Jacques Lacan "TUCHE AND AUTOMATON," inFour Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis', Pierre Bayard, How to Talk About Books You Haven't Gérard Read', Genette, Paratexts', Matthew Kirschenbaum, "Extreme Inscription: A Grammatolosv of the Hard. " Drive in Mechanisms, Henry Petroski, Book on the Book Shelf, Jacques Derrida, "The Double Session"; Edgar Allen Poe, The Purloined Letter, Jacques Lacan, "Seminar on The Purloined Letter', Jacques Derrida, "Le facteur de la vérité," Jacques Derrida, "For the Love of Lacan." Two short papers and weekly written questions on the reading. Requirements: Books: Honore de Balzac, Peau de Chagrin (WildAss's SkinfJacques Derrida, Paper Machine', Jacques Derrida, Dessimination', Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression', Jacques Derrida, The Post Card', Jacques Derrida, Truth in Painting', Cornelia Vismann./ri/tw Law and Media Technology, Franz Kafka, The Trial, E.T.A. -

The End: the Apocalyptic in In-Yer-Face Drama a Thesis

THE END: THE APOCALYPTIC IN IN-YER-FACE DRAMA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY MUSTAFA BAL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE JULY 2009 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ____________________________ Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________ Prof. Dr. Wolf König Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Margaret J-M Sönmez Supervisor Examining Committee Members Dr. Deniz Arslan (METU, ELIT) ____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Margaret Sönmez (METU, ELIT) ____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Can Abanazır (Haliç Uni., ACL) ____________________________ Dr. Hasan İnal (AU, ELIT) ____________________________ Dr. Hülya Yıldız (METU, ELIT) ____________________________ I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Mustafa Bal Signature: iii ABSTRACT THE END: THE APOCALYPTIC IN IN-YER-FACE DRAMA Bal, Mustafa Ph.D., English Literature Program Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Margaret J-M Sönmez July 2009, 236 pages This thesis presents a close analysis of one of the ageless discourses of human life – apocalypse, or the End – within the highly controversial In-Yer-Face drama of the 1990s British stage.