Downloadable Symptomatic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement Gigi Garzio [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sound Ideas University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2018 Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement Gigi Garzio [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Medicine and Health Commons Recommended Citation Garzio, Gigi, "Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement" (2018). Summer Research. 309. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/309 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, when the first smallpox outbreak began and the first vaccine was introduced, there has been vaccine skepticism (Offit, 2015). Smallpox outbreaks, and the fatalities that come with it, continued to spread around the world despite the development of the vaccine. However, between the 1940s and the early 1970s, anti-vaccine sentiment declined due to “three trends: a boom in vaccine science, discovery, and manufacture; public awareness of widespread outbreaks of infectious diseases (measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, polio, and others) and the desire to protect children from these highly prevalent ills; and a baby boom, accompanied by increasing levels of education and wealth” (Poland et al, 2011). These factors led to general public acceptance of vaccines, which resulted in significant decreases in disease outbreaks. However, with less visible outbreaks of disease and more vaccines being added to the childhood vaccination schedule, the presence of the anti-vaccination movement returned in the 1970s (Wolfe, 2002). -

Vaccines and Autism: What You Should Know | Vaccine Education

Q A Vaccines and Autism: What you should know Volume& 1 Summer 2008 Some parents of children with autism are concerned that vaccines are the cause. Their concerns center on three areas: the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine; thimerosal, a mercury-containing preservative previously contained in several vaccines; and the notion that babies receive too many vaccines too soon. Q. What are the symptoms of autism? Q. Does the MMR vaccine cause autism? A. Symptoms of autism, which typically appear during the A. No. In 1998, a British researcher named Andrew Wakefi eld fi rst few years of life, include diffi culties with behavior, social raised the notion that the MMR vaccine might cause autism. skills and communication. Specifi cally, children with autism In the medical journal The Lancet, he reported the stories of may have diffi culty interacting socially with parents, siblings eight children who developed autism and intestinal problems and other people; have diffi culty with transitions and need soon after receiving the MMR vaccine. To determine whether routine; engage in repetitive behaviors such as hand fl apping Wakefi eld’s suspicion was correct, researchers performed or rocking; display a preoccupation with activities or toys; a series of studies comparing hundreds of thousands of and suffer a heightened sensitivity to noise and sounds. children who had received the MMR vaccine with hundreds Autism spectrum disorders vary in the type and severity of of thousands who had never received the vaccine. They found the symptoms they cause, so two children with autism may that the risk of autism was the same in both groups. -

Science Reporting Syllabus: Covering the Environment, Technology and Medicine

1 Science reporting syllabus: Covering the environment, technology and medicine Science reporting is in a moment of extreme transition: Popular science writing is experiencing a renaissance at precisely the moment that traditional media outlets are jettisoning specialized reporters. This creates tremendous opportunity and tremendous challenges. This course makes sure students are prepared to meet those challenges. Course objective This course is designed to acquaint reporters with all aspects of science reporting and writing. It will train participants to view new breakthroughs and discoveries with skepticism and will give students a working knowledge of many of the main areas of science coverage, including the environment, artificial intelligence, and human interaction with technology. There will be lessons on social media, online writing, news and feature writing, and writing long-form narratives. Learning objectives The syllabus is designed to strengthen students’ core competencies in several areas: Determining what sources and outlets can be trusted to discuss controversial or unproven claims. Learning which questions will elicit meaningful responses. Understanding that choosing not to cover a story can be just as important an editorial decision as deciding how to cover it. Evaluating what type of form a journalist is most comfortable with and seeking out ways to work in that form. Course design This course will focus on developing toolkits for evaluating science stories in addition to learning about some specific issues or controversies. It is designed as a workshop course for between 10 and 15 students. An integral part of the course is analyzing and critiquing other students’ work. Readings Required books Deborah Blum, Mary Knudson and Robin Marantz Henig, editors, A Field Guide for Science Writers, 2005. -

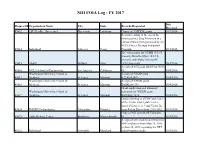

NIH FOIA Log - FY 2017

NIH FOIA Log - FY 2017 Date Request Id Organization Name City State Records Requested Received 45612 LSU Health - Shreveport Shreveport Louisiana Copies of 3 NIDDK grants. 10/3/2016 Records relating to the use of the investigational drug Fostriecin in a human clinical trial sponsored by the NCI's Cancer Therapy Evaluation 45614 Individual Lakeway Texas Program. 10/3/2016 Site visit reports for UTMB (3/1/15- present); Battelle-Ohio (10/1/15- present); and Alpha Genesis-SC 45615 SAEN Milford Ohio (4/1/14-present). 10/3/2016 A copy of NCI grant 1R43CA135915- 45616 UCLA School of Engineering Los Angeles California 01. 10/4/2016 Washington University School of A copy of NIAID grant 45617 Medicine St. Louis Missouri K22AI052407. 10/4/2016 Washington University School of A copy of NHLBI grant 45618 Medicine St. Louis Missouri R01HL081398. 10/4/2016 Grant application and summary Washington University School of statement for NIDDK grant 45619 Medicine St. Louis Missouri K01DK077878. 10/4/2016 Data pertaining to all NIH purchases of the Victor model plate reader (model Victor 1, 2, 3 and Victor X) 45620 IMGEN Technologies Alexandria Virginia from Perkin Elmer from 1999-2012. 10/3/2016 Copy of NEI grant R21EY026438- 45621 Tufts Medical Center Brookline Massachusetts 01. 10/5/2016 A copy of all emails to and from two NIH employees from May 25, 2016 to June 25, 2016 regarding the NTP 45622 Individual Greenbelt Maryland radiofrequency study. 10/5/2016 Date Request Id Organization Name City State Records Requested Received Copies of the RCDC Thesaurus from 45623 Catenion Berlin Other 2010-2014. -

Hearing Before the Committee on Government Reform

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 466 915 EC 309 063 TITLE Autism: Present Challenges, Future Needs--Why the Increased Rates? Hearing before the Committee on Government Reform. House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixth Congress, Second Session (April 6,2000). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Government Reform. REPORT NO House-Hrg-106-180 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 483p. AVAILABLE FROM Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402-9328. Tel: 202-512-1800. For full text: http://www.house.gov/reform. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Autism; *Child Health; Children; *Disease Control; *Etiology; Family Problems; Hearings; *Immunization Programs; Incidence; Influences; Parent Attitudes; *Preventive Medicine; Research Needs; Symptoms (Individual Disorders) IDENTIFIERS Congress 106th; Vaccination ABSTRACT This document contains the proceedings of a hearing on April 6, 2000, before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform. The hearing addressed the increasing rate of children diagnosed with autism, possible links between autism and childhood vaccinations, and future needs of these children. After opening statements by congressmen on the Committee, the statements and testimony of Kenneth Curtis, James Smythe, Shelley Reynolds, Jeana Smith, Scott Bono, and Dr. Wayne M. Danker, all parents of children with autism, are included. Their statements discuss symptoms of autism, vaccination concerns, family problems, financial concerns, and how parents can be helped. The statements and testimony of the second panel are then provided, including that of Andrew Wakefield, John O'Leary, Vijendra K. Singh, Coleen A. Boyle, Ben Schwartz, Paul A. -

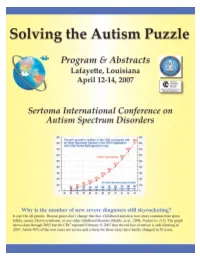

Solving the Autism Puzzle

Contents Foreword .............................. 4 Saturday (Schedule) .................... 18 Acknowledgments by Sertoma . 5 Poster Session 1: Friday 9:30 am . 20 Purpose of Autism07 .................... 6 Poster Session 2: Friday 3:00 pm . 21 Continuing Education Credit . 9 Poster Session 3: Saturday 9:30 am . 22 Thursday (Schedule).................... 11 Exhibitors............................. 25 Downstairs Floor Plan of the Cajundome Partners............................... 25 Convention Center .................. 11 Advertisers............................ 25 Upstairs floor plan for the Cajundome Planning & Organizing Committee . 25 Convention Center .................. 12 Index of Names & Companies . 26 Friday (Schedule) ..................... 13 Copyright © of this Program for Autism07 by the Sertoma Club of Lafayette 2007 Foreword The autism puzzle is about it? This conference addresses that critical question among the most troubling along with questions about the diagnosis and treatment of of today’s world. Severe autism and related disorders. Autism07 has received the autism robs parent and highest possible rating for continuing education from the child of a normal relation American Medical Association. Qualified participants can with each other. Jon receive up to 13.25 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM . Shestack, the producer of Continuing education is also available to dentists, nurses, Father of the Bride and behavior analysts, psychologists, hygienists, social other Hollywood motion workers, occupational therapists, teachers, and -

Interpersonal Communication for Immunization Training for Front Line Workers

1 Participant manual Interpersonal Communication for Immunization Training for Front Line Workers UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Region 2 Interpersonal Communication for Immunization. Participant manual Participant manual Interpersonal Communication for Immunization Training for Front Line Workers UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Region 4 Interpersonal Communication for Immunization. Participant manual Acknowledgements This training package was developed by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, the UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office, and UNICEF Country Office staff in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. We would like to thank Sergiu Tomsa, UNICEF Regional Communication for Development Specialist, Mario Mosquera, UNICEF Regional Communication for Development Adviser and Svetlana Stefanet, UNICEF Regional Immunization Specialist, for their significant contributions to its conceptualization and development. We also thank Fatima Cengic, Health and Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Bosnia and Herzegovina and Jelena Zajeganovic-Jakovljevic, Early Childhood Development Specialist, UNICEF Serbia, as well as Dragoslav Popovic, consultant, the representatives of Institutes of Public Health, academia, health workers, Roma community mediators and civil society organizations from both countries for their support and active engagement in pre-testing and finalizing the package. The materials are based on state-of-the-art resources from UNICEF, the World Health Organization (WHO), European and American Centers for Disease Control, academic journals and the immunization websites of a range of governments and foundations. Authors: Robert Karam, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs Waverly Rennie, Consultant, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs Stephanie Clayton, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs Design: Benussi&theFish Cover Photo: © UNICEF/UN040868/Bicanski © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2019. Some rights reserved. -

Measles, Autism and Vaccination in the Minnesota Somali Community

COMMENTARY POINT OF VIEW Measles, autism and vaccination in the Minnesota Somali community Public health education campaigns must recognize and respect cultural experiences if they are to be successful BY FAIZA AZIZ AND STEVEN H. MILES, MD n March 2011, Minnesota experienced a been largely eliminated in the United large refugee camps in Kenya and Ethio- measles outbreak that arose within, and States, except for occasional imported pia. Poor sanitation, overcrowding, mal- Iwas largely confined to, the Somali com- cases from developing regions still experi- nutrition and violence present challenges munity. Twenty-one cases in Hennepin encing outbreaks. to United Nations vaccination programs in County were linked to a U.S.-born child In Somalia, measles is prevalent and the camps. of Somali descent who had developed leads to high mortality for children Somalis who are accepted for immigra- symptoms after travel to Kenya. Sixteen of younger than 5 years (200 per 1,000 live tion to the United States go through a the 21 individuals had not been fully vac- births). In Somalia and in regional refugee medical examination and receive manda- cinated. Of those, nine were old enough to camps, overcrowding, high rates of lung tory immunizations. Refugees are medi- have received MMR vaccination. Six of the seven infected Somali children were too young to have received vaccinations. Public health officials and news media How can you help someone focused on how the Somali community “ was receptive to Andrew Wakefield’s spuri- you cannot communicate with? ous claim that the measles, mumps and It was hell what I went through with my son. -

'Little Terrors'

Don DeLillo’s Promiscuous Fictions: The Adulterous Triangle of Sex, Space, and Language Diana Marie Jenkins A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of English University of NSW, December 2005 This thesis is dedicated to the loving memory of a wonderful grandfather, and a beautiful niece. I wish they were here to see me finish what both saw me start. Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One 26 The Space of the Hotel/Motel Room Chapter Two 81 Described Space and Sexual Transgression Chapter Three 124 The Reciprocal Space of the Journey and the Image Chapter Four 171 The Space of the Secret Conclusion 232 Reference List 238 Abstract This thesis takes up J. G. Ballard’s contention, that ‘the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else,’ to show that Don DeLillo uses a particular sexual, cultural economy of adultery, understood in its many loaded cultural and literary contexts, as a model for semantic reproduction. I contend that DeLillo’s fiction evinces a promiscuous model of language that structurally reflects the myth of the adulterous triangle. The thesis makes a significant intervention into DeLillo scholarship by challenging Paul Maltby’s suggestion that DeLillo’s linguistic model is Romantic and pure. My analysis of the narrative operations of adultery in his work reveals the alternative promiscuous model. I discuss ten DeLillo novels and one play – Americana, Players, The Names, White Noise, Libra, Mao II, Underworld, the play Valparaiso, The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, and the pseudonymous Amazons – that feature adultery narratives. -

Anti-Vaccine Activists, Web 2.0, and the Postmodern Paradigm –Anoverview Of

Vaccine 30 (2012) 3778–3789 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Vaccine j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm –Anoverview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement ∗ Anna Kata McMaster University, Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, 555 Sanatorium Road Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L9C 1C4 a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Websites opposing vaccination are prevalent on the Internet. Web 2.0, defined by interaction and user- Received 26 May 2011 generated content, has become ubiquitous. Furthermore, a new postmodern paradigm of healthcare has Received in revised form emerged, where power has shifted from doctors to patients, the legitimacy of science is questioned, and 25 September 2011 expertise is redefined. Together this has created an environment where anti-vaccine activists are able to Accepted 30 November 2011 effectively spread their messages. Evidence shows that individuals turn to the Internet for vaccination Available online 13 December 2011 advice, and suggests such sources can impact vaccination decisions – therefore it is likely that anti- vaccine websites can influence whether people vaccinate themselves or their children. This overview Keywords: Anti-vaccination examines the types of rhetoric individuals may encounter online in order to better understand why the anti-vaccination movement can be convincing, despite lacking scientific support for their claims. Tactics Health communication Internet and tropes commonly used to argue against vaccination are described. This includes actions such as skew- Postmodernism ing science, shifting hypotheses, censoring dissent, and attacking critics; also discussed are frequently Vaccines made claims such as not being “anti-vaccine” but “pro-safe vaccines”, that vaccines are toxic or unnatural, Web 2.0 and more. -

"One Nation •¦ Indivisible": Jacques Derrida on the Autoimmunity

RP 36_f4_12-44 11/13/06 11:56 AM Page 15 “ONE NATION . INDIVISIBLE”: JACQUES DERRIDA ON THE AUTOIMMUNITY OF DEMOCRACY AND THE SOVEREIGNTY OF GOD by MICHAEL NAAS DePaul University ABSTRACT During the final decade of his life, Jacques Derrida came to use the trope of autoimmunity with greater and greater frequency. Indeed it today appears that autoimmunity was to have been the last iteration of what for more than forty years Derrida called decon- struction. This essay looks at the consequences of this terminological shift for our under- standing not only of Derrida’s final works (such as Rogues) but of his entire corpus. By taking up a term from the biological sciences that describes the process by which an organism turns in quasi-suicidal fashion against its own self-protection, Derrida was able to rethink the very notion of life otherwise and demonstrate the way in which every sovereign identity, from the self to the nation-state to, most provocatively, God, is open to a process that both threatens to destroy it and gives it its only chance of living on. 1. Pledge of Allegiance I In a volume of remembrance, a volume “in memory of Jacques Derrida,” it is perhaps not inappropriate to begin with a personal memory, even if it might initially appear to have little to do with Derrida.1 It is an old memory, a quintessentially American memory, and one that I suspect many readers of this journal may share. It is the memory of a speech act, a sort of originary profession of faith, the memory of a pledge that I, like most other American school children, recited by heart, that is, in my case, thoughtlessly, mechani- cally, irresponsibly, with the regularity of a tape recording played back in an endless loop, at the beginning of every single school day. -

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM

Expanded Academic ASAP - Document 8/21/13 1:27 PM Title: The rhetoric of drugs: an interview Author(s): Michael Israel Source: differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 5.1 (Spring 1993): p1. Document Type: Interview Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1993 Duke University Press http://dukeupress.edu/ Full Text: Works Cited Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Trans. John Cumming. London: Verso, 1979. Artaud, Antonin. "Letter to the Legislator of the Drug Act." Collected Works of Antonin Artaud. Trans. Victor Conti. Vol. 1. London: Calder, 1968. 58-62. 4 vols. 1968-74. Baudelaire, Charles. "Les Paradis artificiels." Oeuvres completes. Ed. Claude Pichois. Vol. 2. Paris: Gallimard, 1975. The following interview originally appeared in a special issue of Autrement 106 (1989) edited by J.-M. Hervieu and then in the collection, Points de suspension: Entretiens (Paris: Galilee, 1992). Michael Israel's translation was first published in 1-800 2 (1991). Eds. When the sky of transcendence comes to be emptied, a fatal rhetoric fills the void, and this is the fetishism of drug addiction. A: You are not a specialist in the study of drug addiction, yet we suppose that as a philosopher you may have something of particular interest to say on this subject. At the very least, we assume that your thinking might be pertinent here, if only by way of those concepts common both to philosophy and addictive studies, for example dependency, liberty, pleasure, jouissance. JD: O.K. Let us speak then from the point of view of the non-specialist which indeed I am.