Science Reporting Syllabus: Covering the Environment, Technology and Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement Gigi Garzio [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sound Ideas University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2018 Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement Gigi Garzio [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Medicine and Health Commons Recommended Citation Garzio, Gigi, "Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement" (2018). Summer Research. 309. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/309 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, when the first smallpox outbreak began and the first vaccine was introduced, there has been vaccine skepticism (Offit, 2015). Smallpox outbreaks, and the fatalities that come with it, continued to spread around the world despite the development of the vaccine. However, between the 1940s and the early 1970s, anti-vaccine sentiment declined due to “three trends: a boom in vaccine science, discovery, and manufacture; public awareness of widespread outbreaks of infectious diseases (measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, polio, and others) and the desire to protect children from these highly prevalent ills; and a baby boom, accompanied by increasing levels of education and wealth” (Poland et al, 2011). These factors led to general public acceptance of vaccines, which resulted in significant decreases in disease outbreaks. However, with less visible outbreaks of disease and more vaccines being added to the childhood vaccination schedule, the presence of the anti-vaccination movement returned in the 1970s (Wolfe, 2002). -

Vaccines and Autism: What You Should Know | Vaccine Education

Q A Vaccines and Autism: What you should know Volume& 1 Summer 2008 Some parents of children with autism are concerned that vaccines are the cause. Their concerns center on three areas: the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine; thimerosal, a mercury-containing preservative previously contained in several vaccines; and the notion that babies receive too many vaccines too soon. Q. What are the symptoms of autism? Q. Does the MMR vaccine cause autism? A. Symptoms of autism, which typically appear during the A. No. In 1998, a British researcher named Andrew Wakefi eld fi rst few years of life, include diffi culties with behavior, social raised the notion that the MMR vaccine might cause autism. skills and communication. Specifi cally, children with autism In the medical journal The Lancet, he reported the stories of may have diffi culty interacting socially with parents, siblings eight children who developed autism and intestinal problems and other people; have diffi culty with transitions and need soon after receiving the MMR vaccine. To determine whether routine; engage in repetitive behaviors such as hand fl apping Wakefi eld’s suspicion was correct, researchers performed or rocking; display a preoccupation with activities or toys; a series of studies comparing hundreds of thousands of and suffer a heightened sensitivity to noise and sounds. children who had received the MMR vaccine with hundreds Autism spectrum disorders vary in the type and severity of of thousands who had never received the vaccine. They found the symptoms they cause, so two children with autism may that the risk of autism was the same in both groups. -

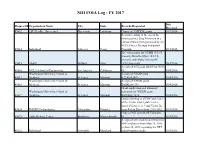

NIH FOIA Log - FY 2017

NIH FOIA Log - FY 2017 Date Request Id Organization Name City State Records Requested Received 45612 LSU Health - Shreveport Shreveport Louisiana Copies of 3 NIDDK grants. 10/3/2016 Records relating to the use of the investigational drug Fostriecin in a human clinical trial sponsored by the NCI's Cancer Therapy Evaluation 45614 Individual Lakeway Texas Program. 10/3/2016 Site visit reports for UTMB (3/1/15- present); Battelle-Ohio (10/1/15- present); and Alpha Genesis-SC 45615 SAEN Milford Ohio (4/1/14-present). 10/3/2016 A copy of NCI grant 1R43CA135915- 45616 UCLA School of Engineering Los Angeles California 01. 10/4/2016 Washington University School of A copy of NIAID grant 45617 Medicine St. Louis Missouri K22AI052407. 10/4/2016 Washington University School of A copy of NHLBI grant 45618 Medicine St. Louis Missouri R01HL081398. 10/4/2016 Grant application and summary Washington University School of statement for NIDDK grant 45619 Medicine St. Louis Missouri K01DK077878. 10/4/2016 Data pertaining to all NIH purchases of the Victor model plate reader (model Victor 1, 2, 3 and Victor X) 45620 IMGEN Technologies Alexandria Virginia from Perkin Elmer from 1999-2012. 10/3/2016 Copy of NEI grant R21EY026438- 45621 Tufts Medical Center Brookline Massachusetts 01. 10/5/2016 A copy of all emails to and from two NIH employees from May 25, 2016 to June 25, 2016 regarding the NTP 45622 Individual Greenbelt Maryland radiofrequency study. 10/5/2016 Date Request Id Organization Name City State Records Requested Received Copies of the RCDC Thesaurus from 45623 Catenion Berlin Other 2010-2014. -

Hearing Before the Committee on Government Reform

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 466 915 EC 309 063 TITLE Autism: Present Challenges, Future Needs--Why the Increased Rates? Hearing before the Committee on Government Reform. House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixth Congress, Second Session (April 6,2000). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Government Reform. REPORT NO House-Hrg-106-180 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 483p. AVAILABLE FROM Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402-9328. Tel: 202-512-1800. For full text: http://www.house.gov/reform. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Autism; *Child Health; Children; *Disease Control; *Etiology; Family Problems; Hearings; *Immunization Programs; Incidence; Influences; Parent Attitudes; *Preventive Medicine; Research Needs; Symptoms (Individual Disorders) IDENTIFIERS Congress 106th; Vaccination ABSTRACT This document contains the proceedings of a hearing on April 6, 2000, before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform. The hearing addressed the increasing rate of children diagnosed with autism, possible links between autism and childhood vaccinations, and future needs of these children. After opening statements by congressmen on the Committee, the statements and testimony of Kenneth Curtis, James Smythe, Shelley Reynolds, Jeana Smith, Scott Bono, and Dr. Wayne M. Danker, all parents of children with autism, are included. Their statements discuss symptoms of autism, vaccination concerns, family problems, financial concerns, and how parents can be helped. The statements and testimony of the second panel are then provided, including that of Andrew Wakefield, John O'Leary, Vijendra K. Singh, Coleen A. Boyle, Ben Schwartz, Paul A. -

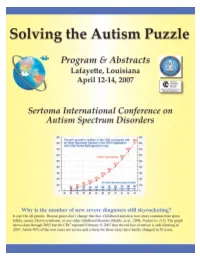

Solving the Autism Puzzle

Contents Foreword .............................. 4 Saturday (Schedule) .................... 18 Acknowledgments by Sertoma . 5 Poster Session 1: Friday 9:30 am . 20 Purpose of Autism07 .................... 6 Poster Session 2: Friday 3:00 pm . 21 Continuing Education Credit . 9 Poster Session 3: Saturday 9:30 am . 22 Thursday (Schedule).................... 11 Exhibitors............................. 25 Downstairs Floor Plan of the Cajundome Partners............................... 25 Convention Center .................. 11 Advertisers............................ 25 Upstairs floor plan for the Cajundome Planning & Organizing Committee . 25 Convention Center .................. 12 Index of Names & Companies . 26 Friday (Schedule) ..................... 13 Copyright © of this Program for Autism07 by the Sertoma Club of Lafayette 2007 Foreword The autism puzzle is about it? This conference addresses that critical question among the most troubling along with questions about the diagnosis and treatment of of today’s world. Severe autism and related disorders. Autism07 has received the autism robs parent and highest possible rating for continuing education from the child of a normal relation American Medical Association. Qualified participants can with each other. Jon receive up to 13.25 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM . Shestack, the producer of Continuing education is also available to dentists, nurses, Father of the Bride and behavior analysts, psychologists, hygienists, social other Hollywood motion workers, occupational therapists, teachers, and -

Interpersonal Communication for Immunization Training for Front Line Workers

1 Participant manual Interpersonal Communication for Immunization Training for Front Line Workers UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Region 2 Interpersonal Communication for Immunization. Participant manual Participant manual Interpersonal Communication for Immunization Training for Front Line Workers UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Region 4 Interpersonal Communication for Immunization. Participant manual Acknowledgements This training package was developed by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, the UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office, and UNICEF Country Office staff in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. We would like to thank Sergiu Tomsa, UNICEF Regional Communication for Development Specialist, Mario Mosquera, UNICEF Regional Communication for Development Adviser and Svetlana Stefanet, UNICEF Regional Immunization Specialist, for their significant contributions to its conceptualization and development. We also thank Fatima Cengic, Health and Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Bosnia and Herzegovina and Jelena Zajeganovic-Jakovljevic, Early Childhood Development Specialist, UNICEF Serbia, as well as Dragoslav Popovic, consultant, the representatives of Institutes of Public Health, academia, health workers, Roma community mediators and civil society organizations from both countries for their support and active engagement in pre-testing and finalizing the package. The materials are based on state-of-the-art resources from UNICEF, the World Health Organization (WHO), European and American Centers for Disease Control, academic journals and the immunization websites of a range of governments and foundations. Authors: Robert Karam, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs Waverly Rennie, Consultant, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs Stephanie Clayton, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs Design: Benussi&theFish Cover Photo: © UNICEF/UN040868/Bicanski © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2019. Some rights reserved. -

Measles, Autism and Vaccination in the Minnesota Somali Community

COMMENTARY POINT OF VIEW Measles, autism and vaccination in the Minnesota Somali community Public health education campaigns must recognize and respect cultural experiences if they are to be successful BY FAIZA AZIZ AND STEVEN H. MILES, MD n March 2011, Minnesota experienced a been largely eliminated in the United large refugee camps in Kenya and Ethio- measles outbreak that arose within, and States, except for occasional imported pia. Poor sanitation, overcrowding, mal- Iwas largely confined to, the Somali com- cases from developing regions still experi- nutrition and violence present challenges munity. Twenty-one cases in Hennepin encing outbreaks. to United Nations vaccination programs in County were linked to a U.S.-born child In Somalia, measles is prevalent and the camps. of Somali descent who had developed leads to high mortality for children Somalis who are accepted for immigra- symptoms after travel to Kenya. Sixteen of younger than 5 years (200 per 1,000 live tion to the United States go through a the 21 individuals had not been fully vac- births). In Somalia and in regional refugee medical examination and receive manda- cinated. Of those, nine were old enough to camps, overcrowding, high rates of lung tory immunizations. Refugees are medi- have received MMR vaccination. Six of the seven infected Somali children were too young to have received vaccinations. Public health officials and news media How can you help someone focused on how the Somali community “ was receptive to Andrew Wakefield’s spuri- you cannot communicate with? ous claim that the measles, mumps and It was hell what I went through with my son. -

Anti-Vaccine Activists, Web 2.0, and the Postmodern Paradigm –Anoverview Of

Vaccine 30 (2012) 3778–3789 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Vaccine j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm –Anoverview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement ∗ Anna Kata McMaster University, Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, 555 Sanatorium Road Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L9C 1C4 a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Websites opposing vaccination are prevalent on the Internet. Web 2.0, defined by interaction and user- Received 26 May 2011 generated content, has become ubiquitous. Furthermore, a new postmodern paradigm of healthcare has Received in revised form emerged, where power has shifted from doctors to patients, the legitimacy of science is questioned, and 25 September 2011 expertise is redefined. Together this has created an environment where anti-vaccine activists are able to Accepted 30 November 2011 effectively spread their messages. Evidence shows that individuals turn to the Internet for vaccination Available online 13 December 2011 advice, and suggests such sources can impact vaccination decisions – therefore it is likely that anti- vaccine websites can influence whether people vaccinate themselves or their children. This overview Keywords: Anti-vaccination examines the types of rhetoric individuals may encounter online in order to better understand why the anti-vaccination movement can be convincing, despite lacking scientific support for their claims. Tactics Health communication Internet and tropes commonly used to argue against vaccination are described. This includes actions such as skew- Postmodernism ing science, shifting hypotheses, censoring dissent, and attacking critics; also discussed are frequently Vaccines made claims such as not being “anti-vaccine” but “pro-safe vaccines”, that vaccines are toxic or unnatural, Web 2.0 and more. -

Responding with Empathy to Parents' Fears of Vaccinations

FeaTURE REVIEW “I’ve Heard Some Things That Scare Me” Responding With Empathy to Parents’ Fears of Vaccinations by Kenneth Haller, MD & Anthony Scalzo, MD had suffered a recent persistent cough for a few weeks but had experienced no fever. Despite her age, the baby had not received any immunizations on the advice of the family’s chiropractor. Abstract The family also said that they had The Lancet’s “read some stuff on the Internet 1998 publication of about shots and autism,” and they “Ileal-lymphoid-nodular felt the baby would be better off not hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, getting immunizations than “taking and pervasive developmental a chance” that vaccines might harm disorder in children” by Andrew her. The baby’s nasopharyngeal swab Wakefield, et. al., positing a was positive for pertussis, as was her causal relationship between follow-up culture. She required oxygen MMR vaccine and autism in by nasal cannula for five days and was children, set off a media storm sent home after she was weaned to and galvanized the anti-vaccine room air. The parents were counseled movement. In this paper, that the baby would likely still have a centuries-old fears of vaccination cough for many weeks to come. and the history of autism as a This was one of three pertussis medical diagnosis are considered, cases seen by the clinic medicine and an affective, family-centered attending during one month on approach to dealing with inpatient service, the first time in his parental fears by physicians is career that he had seen more than one proposed. -

AUTISM ONE / GENERATION RESCUE 2010 CONFERENCE MAY 24-30, 2010 Chicago, Illinois

GENERATION RESCUE AUTISMONE AND GENERATION RESCUE autism is reversible JOIN FORCES TO HELP CHILDREN Chicago 2010 Conference Monday, May 24 – Sunday, May 30 AUTISM ONE / GENERATION RESCUE 2010 CONFERENCE MAY 24-30, 2010 chicago, Illinois REDEFINING AUTISM In order to find effective solutions, you need to correctly define the problem. Mainstream medicine hasn’t accurately identified the problems underlying an autism diagnosis. The doctors, researchers, and therapists at the Autism One/Generation Rescue conference correctly define the problem. That way, they can help you, your child, and your family find the solutions. KEYNOTE SPEAKERS: JENNY McCARTHY & SARAH SCHEFLEN The most comprehensive autism conference special features for 2010 include: internationally, the Autism One/Generation Rescue conference gives you choices from content areas such as: l prediction/prevention track l expanded seizures presentation track l biomedical research and treatments l expanded pANDAs coverage l educational, behavioral, communication, l environmental issues & chronic and adjunct therapies diseases symposium l complementary alternative medicine l expanded advocacy track & training l government, legal, and personal issues and advocacy l Student scholars for Autism program l adolescent, adult, and Asperger’s issues Choose from among 140+ speakers including: Daniel Barth, phD Brian King, LcsW Narasimham parinandi, phD Ken Bock, MD Miroslav Kovacevic, MD William parker, phD Britt collins, Ms, OTR/L susan Kratz, OTR, csT Alexander Rotenberg, MD, phD sydney Finegold, MD M. elizabeth Latimer, MD Kendal stewart, MD Jay Gordon, MD Jeffrey Lewine, phD Kyle van Dyke, MD Louise Kuo Habakus, HHp Roy Leonardi, edD Anju Usman, MD Martha Herbert, MD, phD valerie Maclean Andrew Wakefield, MD Laura Hewitson, phD Beth Alison Maloney William Walsh, phD Harumi Jyonouchi, MD Woody McGinnis, MD Amy Yasko, phD Jerry Kartzinel, MD Nancy Mullan, MD savely Yurkovsky, MD HOpe Is ALWAYs ReAL .. -

Public Trust in Vaccines

MILESTONES MILESTONE 19 have been attributed to the drop in vaccina- tion. Geopolitical tensions can also contribute to vaccine hesitancy. The false belief that polio Public trust in vaccines vaccines were contaminated with oestradiol as part of a US-led plot to cause infertility in Muslims prompted the Kano state government in Nigeria to suspend polio vaccination between 2003 and 2004. This caused a resur- gence of polio in Nigeria and neighbouring regions, even as far as Indonesia. Negative public perception of vaccination is not a modern-day phenomenon. In1802, the English satirist James Gillray depicted the unfortunate recipients of Edward Jenner’s cowpox vaccine with bovine projections emitting from their skin and various orifices. Jenner and other early advocates of inocu- lation also faced theological opposition. A sermon by the Rev. Edmund Massey in 1772 (some 24 years before Jenner’s vaccination of James Phipps) denounced the ‘dangerous and sinful practice of inoculation’. Massey preached that ‘diseases are sent... for the pun- ishment of our sins’. Even today, parents can refuse otherwise mandatory vaccines on the Satirical artwork from 1802 by James Gillray, showing the supposed effects of using cowpox as a vaccine against smallpox. grounds of religious beliefs. Credit: GL Archive / Alamy Stock Photo In the midst of a global pandemic, the issue of public confidence in vaccination is more In early February 2010, The Lancet medical the refusal of perfectly urgent than ever. The WHO has described vac- journal retracted a case study it had published cine hesitancy as one of the top ten threats to 12 years earlier. -

Vaccine Hesitancy and Fake News: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Italy

HEDG HEALTH, ECONOMETRICS AND DATA GROUP WP 19/03 Vaccine Hesitancy and Fake News: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Italy Vincenzo Carrieri; Leonardo Madio and Francesco Principe February 2019 http://www.york.ac.uk/economics/postgrad/herc/hedg/wps/ Vaccine Hesitancy and Fake News: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Italy Vincenzo Carrieri¶ Leonardo Madio† Francesco Principe♠ Abstract The spread of fake news and misinformation on social media is blamed to be one of the main causes of vaccine hesitancy, one of the ten threats to global health according to World Health Organization. This paper studies the effect of diffusion of fake news on immunization rates in Italy by exploiting a quasi-experiment occurred in 2012, when the Court of Rimini officially recognized a causal link between MMR vaccine and autism and awarded injury compensation. To this end, we exploit virality of fake news following the 2012 Italian Court’s ruling along with the intensity in the exposure to non-traditional media driven by regional infrastructural differences in Internet broadband coverage. Using a Difference-in-Difference (DiD) regression on regional panel data, we show that the spread of fake news caused a drop in children immunization rates for all types of vaccines. JEL Codes: I12; I18; L82; L86. Keywords: Fake news; vaccine hesitancy; children immunization rates, social media, Internet. ________________________________ ¶ Department of Law, Economics and Sociology, “Magna Graecia” University, Catanzaro, Italy; RWI- Research Network, Essen, Germany; HEDG, University of York, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected] † CORE, Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; CESifo Research Network, Munich, Germany; HEDG, University of York, United Kingdom.