Anti-Vaccine Activists, Web 2.0, and the Postmodern Paradigm –Anoverview Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement Gigi Garzio [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sound Ideas University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2018 Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement Gigi Garzio [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Medicine and Health Commons Recommended Citation Garzio, Gigi, "Values, Justifications, and Perspectives Connected to the Anti-Vaccination Movement" (2018). Summer Research. 309. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/309 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, when the first smallpox outbreak began and the first vaccine was introduced, there has been vaccine skepticism (Offit, 2015). Smallpox outbreaks, and the fatalities that come with it, continued to spread around the world despite the development of the vaccine. However, between the 1940s and the early 1970s, anti-vaccine sentiment declined due to “three trends: a boom in vaccine science, discovery, and manufacture; public awareness of widespread outbreaks of infectious diseases (measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, polio, and others) and the desire to protect children from these highly prevalent ills; and a baby boom, accompanied by increasing levels of education and wealth” (Poland et al, 2011). These factors led to general public acceptance of vaccines, which resulted in significant decreases in disease outbreaks. However, with less visible outbreaks of disease and more vaccines being added to the childhood vaccination schedule, the presence of the anti-vaccination movement returned in the 1970s (Wolfe, 2002). -

Vaccines and Autism: What You Should Know | Vaccine Education

Q A Vaccines and Autism: What you should know Volume& 1 Summer 2008 Some parents of children with autism are concerned that vaccines are the cause. Their concerns center on three areas: the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine; thimerosal, a mercury-containing preservative previously contained in several vaccines; and the notion that babies receive too many vaccines too soon. Q. What are the symptoms of autism? Q. Does the MMR vaccine cause autism? A. Symptoms of autism, which typically appear during the A. No. In 1998, a British researcher named Andrew Wakefi eld fi rst few years of life, include diffi culties with behavior, social raised the notion that the MMR vaccine might cause autism. skills and communication. Specifi cally, children with autism In the medical journal The Lancet, he reported the stories of may have diffi culty interacting socially with parents, siblings eight children who developed autism and intestinal problems and other people; have diffi culty with transitions and need soon after receiving the MMR vaccine. To determine whether routine; engage in repetitive behaviors such as hand fl apping Wakefi eld’s suspicion was correct, researchers performed or rocking; display a preoccupation with activities or toys; a series of studies comparing hundreds of thousands of and suffer a heightened sensitivity to noise and sounds. children who had received the MMR vaccine with hundreds Autism spectrum disorders vary in the type and severity of of thousands who had never received the vaccine. They found the symptoms they cause, so two children with autism may that the risk of autism was the same in both groups. -

Science Reporting Syllabus: Covering the Environment, Technology and Medicine

1 Science reporting syllabus: Covering the environment, technology and medicine Science reporting is in a moment of extreme transition: Popular science writing is experiencing a renaissance at precisely the moment that traditional media outlets are jettisoning specialized reporters. This creates tremendous opportunity and tremendous challenges. This course makes sure students are prepared to meet those challenges. Course objective This course is designed to acquaint reporters with all aspects of science reporting and writing. It will train participants to view new breakthroughs and discoveries with skepticism and will give students a working knowledge of many of the main areas of science coverage, including the environment, artificial intelligence, and human interaction with technology. There will be lessons on social media, online writing, news and feature writing, and writing long-form narratives. Learning objectives The syllabus is designed to strengthen students’ core competencies in several areas: Determining what sources and outlets can be trusted to discuss controversial or unproven claims. Learning which questions will elicit meaningful responses. Understanding that choosing not to cover a story can be just as important an editorial decision as deciding how to cover it. Evaluating what type of form a journalist is most comfortable with and seeking out ways to work in that form. Course design This course will focus on developing toolkits for evaluating science stories in addition to learning about some specific issues or controversies. It is designed as a workshop course for between 10 and 15 students. An integral part of the course is analyzing and critiquing other students’ work. Readings Required books Deborah Blum, Mary Knudson and Robin Marantz Henig, editors, A Field Guide for Science Writers, 2005. -

To Vaccinate Or Not to Vaccinate: a Qualitative Description of the Information Available on Popular Search Engines Regarding the Vaccine Debate

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 2016 To Vaccinate or Not To Vaccinate: A Qualitative Description of the Information Available on Popular Search Engines Regarding the Vaccine Debate. Madeline Rhinesmith Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rhinesmith, Madeline, "To Vaccinate or Not To Vaccinate: A Qualitative Description of the Information Available on Popular Search Engines Regarding the Vaccine Debate." (2016). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 343. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/343 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Vaccinate or Not To Vaccinate: A Qualitative Description of the Information Available on Popular Search Engines Regarding the Vaccine Debate. A Thesis Presented to the Department of Science, Technology and Society College of Liberal Arts in Sciences and The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Madeline Louise Rhinesmith April 25, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 6 METHODS 12 TABLE 1 15 RESULTS 21 TABLE 2 22 DISCUSSION 23 TABLE 3 24 CONCLUSION 30 REFERENCE LIST 32 Abstract The current study looks at the assumption that that more information, along with improved access to that information could lead to more informed decisions through evaluating and critically reflecting on the vaccine debate. -

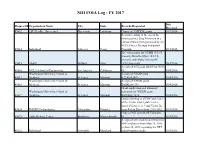

NIH FOIA Log - FY 2017

NIH FOIA Log - FY 2017 Date Request Id Organization Name City State Records Requested Received 45612 LSU Health - Shreveport Shreveport Louisiana Copies of 3 NIDDK grants. 10/3/2016 Records relating to the use of the investigational drug Fostriecin in a human clinical trial sponsored by the NCI's Cancer Therapy Evaluation 45614 Individual Lakeway Texas Program. 10/3/2016 Site visit reports for UTMB (3/1/15- present); Battelle-Ohio (10/1/15- present); and Alpha Genesis-SC 45615 SAEN Milford Ohio (4/1/14-present). 10/3/2016 A copy of NCI grant 1R43CA135915- 45616 UCLA School of Engineering Los Angeles California 01. 10/4/2016 Washington University School of A copy of NIAID grant 45617 Medicine St. Louis Missouri K22AI052407. 10/4/2016 Washington University School of A copy of NHLBI grant 45618 Medicine St. Louis Missouri R01HL081398. 10/4/2016 Grant application and summary Washington University School of statement for NIDDK grant 45619 Medicine St. Louis Missouri K01DK077878. 10/4/2016 Data pertaining to all NIH purchases of the Victor model plate reader (model Victor 1, 2, 3 and Victor X) 45620 IMGEN Technologies Alexandria Virginia from Perkin Elmer from 1999-2012. 10/3/2016 Copy of NEI grant R21EY026438- 45621 Tufts Medical Center Brookline Massachusetts 01. 10/5/2016 A copy of all emails to and from two NIH employees from May 25, 2016 to June 25, 2016 regarding the NTP 45622 Individual Greenbelt Maryland radiofrequency study. 10/5/2016 Date Request Id Organization Name City State Records Requested Received Copies of the RCDC Thesaurus from 45623 Catenion Berlin Other 2010-2014. -

03-584V • FRED KING and MYLINDA KING, Parents of Jordan King, a Minor V. SECRETARY OF

In the United States Court of Federal Claims OFFICE OF SPECIAL MASTERS No. 03-584V (Filed: September 22, 2011) TO BE PUBLISHED1 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * FRED KING and MYLINDA KING, * parents of Jordan King, a minor, * Vaccine Act Interim Costs; * Fees for Omnibus Proceedings; Petitioners, * Expert Costs; Expenditures * For Original Research v. * Articles; Dr. Mark Geier. * SECRETARY OF HEALTH AND * HUMAN SERVICES, * * Respondent. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * DECISION ON REMAND CONCERNING INTERIM COSTS HASTINGS, Special Master. In this case under the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (hereinafter “the Program”), the petitioners seek, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 300aa-15(e),2 an interim award for attorneys’ costs incurred in the course of the petitioners’ attempt to obtain Program compensation. On December 13, 2010, I issued a Decision Awarding Interim Costs, which was the fifth award of interim fees and/or costs issued in this case. The petitioners sought review of that Decision, and on 1 Because I have designated this document to be published, each party has 14 days within which to request redaction “of any information furnished by that party (1) that is trade secret or commercial or financial information and is privileged or confidential, or (2) that are medical files and similar files the disclosure of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy.” Vaccine Rule 18(b); 42 U.S.C. § 300aa-12(d)(4)(B). Otherwise, this entire document will be available to the public. 2 The applicable statutory provisions defining the Program are found at 42 U.S.C. § 300aa- 10 et seq. (2006). Hereinafter, for ease of citation, all “§” references will be to 42 U.S.C. -

An Interview with Sharyl Attkinson

Exclusive: An interview with investigative reporter Sharyl Attkisson by Jon Rappoport April 25, 2014; www.nomorefakenews.com Before her recent resignation from CBS, Sharyl Attkisson was a mainstream news star. Multiple Emmys. CNN anchor, CBS anchor on stories about space exploration. Host of CBS’ News Up to the Minute. PBS host for Health Week. Investigative reporter for CBS. Attkisson dug deep into Fast&Furious, Benghazi, and the ill-effects of vaccines. Too deep. Her bosses shut her down and didn’t air key stories. She now has her own website, sharylattkisson.com. She is writing a book, Stonewalled: My Fight for the Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation and Harassment in Obama’s Washington. It’s not every day that a major mainstream journalist leaves the fold and then seeks to expose the corruption that impinged on her work. She agreed to do an email interview. Some of the questions I sent went to the heart of her book-in-progress, so she declined to answer them. However, her answers to my other questions were revealing and explosive. I know you’ve had problems with your Wikipedia page. What happened there? Long story short: there is a concreted effort by special interests who exploit Wikipedia editing privileges to control my biographical page to disparage my reporting on certain topics and skew the information. Judging from the editing, the interest(s) involved relates to the pharmaceutical/vaccine industry. I am far from alone. There is an entire Wikipedia subculture that exists to control pages and topics, and another one that watchdogs all that’s gone wrong with Wikipedia (Wikipediocracy). -

(No Jab, No Pay) Bill 2015 Submission

16 October, 2015 The Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs PO Box 6100 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Committee Secretary, Re: Submission to the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee Inquiry into the Social Services Legislation Amendment (No Jab, No Pay) Bill 2015 I am a Solicitor who has practiced in areas of law that have pertained to the issue of vaccination. Consequently, having conversed with professionals in various scientific and medical fields of practice on this issue and prepared matters for hearing based on their expertise, I make the following submission to emphasize the extent that the proposed legislation breaches fundamental human rights and the government’s responsibilities to it’s families and children. According to the Social Services Legislation Amendment (No jab, No pay) Bill 2015 Explanatory Memorandum and Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights: “This Bill will introduce a 2015 Budget measure relevant to families. This Bill amends the immunisation requirements for child care benefit, child care rebate and the family tax benefit Part A supplement. The changes will tighten the existing immunisation requirements for these payments, reinforcing the importance of immunisation and protecting public health, especially for children. From 1 January 2016, this measure makes these payments conditional on meeting the childhood immunisation requirements for children at all ages. Exemptions will only apply for valid medical reasons, or if the Secretary has determined in writing that a child meets the immunisation requirements. The Secretary will be able to determine that a child meets the immunisation requirements after considering any decision-making principles set out in a legislative instrument made by the Minister. -

Union Calendar No. 881

1 Union Calendar No. 881 115TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 115–1114 ACTIVITIES OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 2019 (Pursuant to House Rule XI, 1(d)(1)) Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdys.gov http://oversight.house.gov/ JANUARY 2, 2016.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–945 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:03 Jan 08, 2019 Jkt 033945 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR1114.XXX HR1114 SSpencer on DSKBBXCHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM TREY GOWDY, South Carolina, Chairman JOHN DUNCAN, Tennessee ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland DARRELL ISSA, California CAROLYN MALONEY, New York JIM JORDAN, Ohio ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MARK SANFORD, South Carolina Columbia JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan WILLIAM LACY CLAY, Missouri PAUL GOSAR, Arizona STEPHEN LYNCH, Massachusetts SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee JIM COOPER, Tennessee VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky ROBIN KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDA LAWRENCE, Michigan DENNIS ROSS, Florida BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey MARK WALKER, North Carolina RAJA KRISHNAMOORTHI, Illinois ROD BLUM, Iowa JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland JODY B. HICE, Georgia JIMMY GOMEZ, California STEVE RUSSELL, Oklahoma PETER WELCH, Vermont GLENN GROTHMAN, Wisconsin MATT CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania -

The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program: Awareness, Perception, and Communication Considerations

The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program: Awareness, Perception, and Communication Considerations Developing a Comprehensive National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program Research Report Presented by Banyan Communications and Altarum Institute For the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration Division of Vaccine Injury Compensation June 2010 Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Background ................................................................................................................. 1 a. VICP BACKGROUND: RELATED LEGISLATION ................................................................................................. 2 2. Review of the VICP Literature ................................................................................................................. 4 a. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................. 4 b. VICP PERCEPTION AND REACTION ................................................................................................................ 4 c. VICP MESSAGING AND PROMOTION ............................................................................................................. 7 3. Scan of the Field: VICP Players, Media, and the Online Environment .................................................... 12 a. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................. 12 b. VICP AND -

Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons a Thesis

Disablement, Diversity, Deviation: Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Sarah Gibbons 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation brings disability studies and postcolonial studies into dialogue with discourse surrounding risk in the environmental humanities. The central question that it investigates is how critics can reframe and reinterpret existing threat registers to accept and celebrate disability and embodied difference without passively accepting the social policies that produce disabling conditions. It examines the literary and rhetorical strategies of contemporary cultural works that one, promote a disability politics that aims for greater recognition of how our environmental surroundings affect human health and ability, but also two, put forward a disability politics that objects to devaluing disabled bodies by stigmatizing them as unnatural. Some of the major works under discussion in this dissertation include Marie Clements’s Burning Vision (2003), Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People (2007), Gerardine Wurzburg’s Wretches & Jabberers (2010) and Corinne Duyvis’s On the Edge of Gone (2016). The first section of this dissertation focuses on disability, illness, industry, and environmental health to consider how critics can discuss disability and environmental health in conjunction without returning to a medical model in which the term ‘disability’ often designates how closely bodies visibly conform or deviate from definitions of the normal body. -

The Case Study of Crossfire Hurricane

TIMELINE: Congressional Oversight in the Face of Executive Branch and Media Suppression: The Case Study of Crossfire Hurricane 2009 FBI opens a counterintelligence investigation of the individual who would become Christopher Steele’s primary sub-source because of his ties to Russian intelligence officers.1 June 2009: FBI New York Field Office (NYFO) interviews Carter Page, who “immediately advised [them] that due to his work and overseas experiences, he has been questioned by and provides information to representatives of [another U.S. government agency] on an ongoing basis.”2 2011 February 2011: CBS News investigative journalist Sharyl Attkisson begins reporting on “Operation Fast and Furious.” Later in the year, Attkisson notices “anomalies” with several of her work and personal electronic devices that persist into 2012.3 2012 September 11, 2012: Attack on U.S. installations in Benghazi, Libya.4 2013 March 2013: The existence of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s private email server becomes publicly known.5 May 2013: o News reports reveal Obama’s Justice Department investigating leaks of classified information and targeting reporters, including secretly seizing “two months of phone records for reporters and editors of The Associated Press,”6 labeling Fox News reporter James Rosen as a “co-conspirator,” and obtaining a search warrant for Rosen’s personal emails.7 May 10, 2013: Reports reveal that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) targeted and unfairly scrutinized conservative organizations seeking tax-exempt status.8