113 Adam Patrick Robinson Thebehaviourofgiovannimorone,Likethatofreginaldpole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Catholic Reformation 1545

10$ THE CATHOLIC REFORMATION $ 1545 - 1648AD In this article, we will look at: Hadrian (1459-1523), sometimes called Adrian, succeeds Pope Leo X. He is a respected scholar and • Catholic reform prior to the Council of Trent former teacher of Erasmus. This Dutchman is the • Council of Trent last non-Italian pope until the election of John Paul II • Implementing the Council in 1978. He is in Spain when elected pope. But • The Jesuits before leaving for Rome, he writes a stern letter to • Catholic mystics and activists the College of Cardinals stating that he is coming not to celebrate with them but to chastise and correct • Enduring legacy of Trent them. He also writes to secular leaders throughout There is no doubt that the Catholic Church is in dire the Empire, criticizing them for creating a culture need of reform when Martin Luther posts his Ninety- prone to clerical corruption. Five Theses on the door of the church in Wittenberg in 1517. Many of the popes and other church leaders In one such letter to a Prince, Hadrian said: “All of lead scandalous lives and neglect the pastoral care of us, prelates and clergy, have turned aside from the their people. road of righteousness and for a long time now there has been not even one who did good…. You must Having said that, some people within the Church try therefore promise in our name that we intend to exert to bring reform. Cardinal de Cisneros, a Catholic ourselves so that, first of all, the Roman Curia, from leader in Spain from 1495 to1517, brings about many which perhaps all this evil took its start, may be reforms in his country, which is the main reason improved. -

PDF Herunterladen

annuarium historiae conciliorum 48 (2016/2017) 440-462 brill.com/anhc What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate Dr. Antonio Gerace Fondazione per le Scienze Religiose Giovanni XXIII, Bologna, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven [email protected] Abstract Before the issue of the Insuper decree (1546), by means of which the Council Fathers declared the Vulgate to be the ‘authentic’ Bible for Catholic Church, Girolamo Seri- pando took few notes discussing the need of a threefold Bible, in Latin, Greek and He- brew, as he stressed in the General Congregation on 3 April 1546. Only Rongy (1927/28), Jedin (1937) and François/Gerace (2018) paid attention to this document, preserved at the National Library in Naples in a manuscript of the 17th century (Ms. Vind. Lat. 66, 123v–127v). In this article, the author offers the very first transcription of these notes together with the analysis of Seripando’s sources, providing a new primary source to early modern historians. Keywords Girolamo Seripando – Vulgate – Council of Trent – John Driedo – San Giovanni a Carbonara Library 1 Introduction The aim of this article is to offer the very first transcription of Girolamo Seri- pando (1493–1563)’s unedited notes titled De Libris Sanctis, the only copy of 1 1 I thank a lot Prof. Dr. Violet Soen (ku Leuven) and Prof. Dr. Brad Gregory (University of Notre Dame), who helped me to date the manuscript that contains Seripando’s De Libris Sanctis. Moreover, thanks go to Ms Eliza Halling, who carefully checked the English of this article. © verlag ferdinand schöningh, 2019 | doi:10.30965/25890433-04802007Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 01:00:28PM via free access <UN> What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate 441 which is contained in a 17th century manuscript,1 still preserved in Naples at the National Library (Ms. -

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

XVII. Other XVI Century Developments A. Anabaptism 1. Defined And

XVII. Other XVI Century Developments A. Anabaptism 1. Defined and described a. “baptize again” = believer’s baptism b. classed as “Radical Reformation” = Restitutionists vs. Reformers c. most representatives were very pious 1) Bible only; many reject theology and the fathers 2) took names “Brethren” or “Christians” 3) Christians should have no part in civil government 4) rejected state church 5) many were post-mil chiliasts; some were Socinian 2. Fanaticism a. Melchior Hoffmann in Strasbourg from 1522-1548 declares it the New Jerusalem b. Munster fiasco (ca. 1534-1536) 1) Jan Mathys a) self-proclaimed “reincarnated Enoch” to usher in the Kingdom of God b) opponents purged from New Jerusalem c) community of goods instituted 2) Jan of Leyden a) self-crowned “King David” after Mathys killed during siege b) appointed 12 apostles c) polygamy promoted 3) Lutherans and RCs unite in conquest 4) black eye for Anabaptists c. Menno Simons (1496-1561) 1) Dutch RC priest converted by Luther’s writings a) evolved into Anabaptist b) active in Holland and N. Germany 2) wrote vs. Protestants and radical Anabaptists like Jan of Leyden 3) ideas of the Mennonites a) community of believers b) non-violence and non-resistance; pacifism c) distrust of learning & dogma d) footwashing 4) spread a) before 1700 to Poland and Russia and Switzerland b) after 1700, many Swiss Mennonites to N. America 10.1 * B. Counter-reformation 1. early attitude of the papacy a. popes not the main force behind RC reforms b. significant popes 1) Paul III (1534-1549) 1540 - approved Jesuits 1542 - initiated Roman Inquisition 1545 - presided at opening session of Trent 2) Paul IV [Cardinal Caraffa] (1555-1559) a) unwilling to make concessions to Protestants b) nepotism is somewhat curbed 3) Pius IV eradicates all nepotism c. -

AP European History Trouble in the Church • Babylonian Captivity – 1309-78 • Great Schism – 1378-1417

The Reformation AP European History Trouble in the Church • Babylonian Captivity – 1309-78 • Great Schism – 1378-1417 Clement VII Leo X w/ Giulio Seven Sacraments • Baptism – takes away Original Sin • Confirmation – receive Holy Ghost • Holy Eucharist – Body / Blood of Christ • Penance – confession; takes away sin • Extreme Unction – prepares you for death • Holy Orders – preparation for priesthood • Matrimony – marriage; obey God’s law Signs of Disorder •What are some of the problems in the Church? Thomas a Kempis John Wyclif (1328-1384) John Hus (1369-1415) Martin Luther (1483-1546) Pope Leo X • Grants permission to Archbishop of Magdeberg, Albert, to sell indulgences John Tetzel Indulgences Tetzel and Indulgence Box Actual Letter of Indulgence 95 Thesis - Wittenberg Charles V Holy Roman Empire • Eventually becomes an aristocratic federation of seven electors • Archbishops of Mainz, Trier, Cologne • Margrave of Brandenburg • Duke of Saxony • Count Palatine of the Rhine • King of Bohemia Duke Frederick of Saxony Edict of Worms • Diet of Worms – Jan. through April 1521 – Presided by Charles V – Frederick III, Elector of Saxony offers protection • Edict of Worms – May 1521 states: – Luther = outlaw, heretic and banned all of his literature – Open season to kill Luther (without legal consequence) Katharina von Bora Luther’s Four Questions • How is a person to be saved? • Where does religious authority reside? • What is the Church? • What is the highest form of Christian life? Luther’s Sacraments • Baptism • Holy Eucharist Social Impact of -

On the Vacancy of the Apostolic See by Bishop Mark A. Pivarunas, CMRI 14/03/18, 7�55 PM

On the Vacancy of the Apostolic See by Bishop Mark A. Pivarunas, CMRI 14/03/18, 7*55 PM HOME TRADITIONAL CATHOLIC FAITH MASS LOCATIONS PUBLICATIONS CMRI LINKS STORE PHOTOS CONTACT US CMRI Home > Article Index > Sedevacantist Position On the Vacancy of the Apostolic See By Bishop Mark A. Pivarunas, CMRI Our conference on the vacancy of the Apostolic See, the sedevacantist position, is most important, for it is a theological position which is very misunderstood, often misrepresented, and emotionally difficult for many groups. But before we proceed on this topic, it is paramount to stress that it is because of our belief in the Papacy and in Papal Infallibility that we necessarily must reject Paul VI, John Paul II and Benedict XVI as legitimate Popes. Many accuse us of rejection of the papacy. That is furthermost from the truth. In our earlier conference, we made reference to the main errors of religious indifferentism, false ecumenism and religious liberty which have infected the Conciliar Church of Vatican II. It is for us to demonstrate that the true Catholic Church—the Pope and the Bishops in union with him—could not promulgate such errors to the universal Church, and that no true Pope could promulgate a defective liturgy (Novus Ordo Missae) and a sacrilegious law (1983 Code of Canon Law 844.3 and 4 Communion to non-Catholics). It is for us to demonstrate that men who promulgate heresy are heretics; and as such, they lose the authority in the Church Although we can consider many different aspects of our position with the papacy, it will be sufficient for us today to limit our studies to a few main premises upon which our conclusion (the vacancy) rests. -

India- Holy See Relations Diplomatic Relations Between India and The

India- Holy See relations Diplomatic relations between India and the Holy See were established soon after India’s independence. India’s Ambassador in Berne, Switzerland, has traditionally been accredited to the Holy See which maintains a Nunciature (Embassy) in New Delhi, presently headed by a Nuncio (Ambassador). 2. India has the second largest Catholic population in Asia which also including those from Kerala dating from Apostolic times. With a shortage of priests and nuns from developed countries, a large number of Indians have joined various Roman Catholic Orders and a number of them have started occupying high positions within the Catholic Church institutions including those in Rome. India and Indians have a positive image in the Catholic community. 3. Although the strength of the Christian (and hence the Catholic) community forms only a small proportion of India’s population, the Holy See has always acknowledged the importance of India, both in global and Asian terms. There have been three Papal visits to India so far. The first Pope to visit India was Pope Paul IV, who came to Bombay in 1964 to attend the International Eucharistic Congress. Pope John Paul II visited India in February 1986 and November 1999. During his latter visit, he met the President, Vice President, Prime Minister and EAM. He participated in the concluding session of Synod of Bishops of Asia at which he signed and released post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation. 4. Several Indian dignitaries have, from time to time, called on the Pope in the Vatican. These have included the late Smt. Indira Gandhi in 1981 and Shri I.K. -

Introduction: the Spirituali and Their Goals

NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 19, 2014 NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. MALS Mentor: Michael Collins, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Beginning in the 1530’s, groups of scholars, poets, artists and Catholic Church prelates came together in Italy in a series of salons and group meetings to try to move themselves and the Church toward a concept of faith that was centered on the individual’s personal relationship to God and grounded in the gospels rather than upon Church tradition. The most prominent of these groups was known as the spirituali, or spiritual ones, and it included among its members some of the most renowned and celebrated people of the age. And yet, despite the fame, standing and unrivaled access to power of its members, the group failed utterly to achieve any of its goals. By 1560 all of the spirituali were either dead, in exile, or imprisoned by the Roman Inquisition, and their ideas had been completely repudiated by the Church. The question arises: how could such a “conspiracy of geniuses” have failed so abjectly? To answer the question, this paper examines the careers of three of the spirituali’s most prominent members, Vittoria Colonna, Michelangelo and Reginald Pole. -

Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses School of Theology and Seminary 3-13-2018 Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs Stephanie Falkowski College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Falkowski, Stephanie, "Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs" (2018). School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses. 1916. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers/1916 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Theology and Seminary at DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT QUITE CALVINIST: CYRIL LUCARIS A RECONSIDERATION OF HIS LIFE AND BELIEFS by Stephanie Falkowski 814 N. 11 Street Virginia, Minnesota A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Seminary of Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Theology. SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND SEMINARY Saint John’s University Collegeville, Minnesota March 13, 2018 This thesis was written under the direction of ________________________________________ Dr. Shawn Colberg Director _________________________________________ Dr. Charles Bobertz Second Reader Stephanie Falkowski has successfully demonstrated the use of Greek and Latin in this thesis. -

What Is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando's Notes on the Vulgate

annuarium historiae conciliorum 48 (2016/2017) 440-462 brill.com/anhc What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate Dr. Antonio Gerace Fondazione per le Scienze Religiose Giovanni XXIII, Bologna, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven [email protected] Abstract Before the issue of the Insuper decree (1546), by means of which the Council Fathers declared the Vulgate to be the ‘authentic’ Bible for Catholic Church, Girolamo Seri- pando took few notes discussing the need of a threefold Bible, in Latin, Greek and He- brew, as he stressed in the General Congregation on 3 April 1546. Only Rongy (1927/28), Jedin (1937) and François/Gerace (2018) paid attention to this document, preserved at the National Library in Naples in a manuscript of the 17th century (Ms. Vind. Lat. 66, 123v–127v). In this article, the author offers the very first transcription of these notes together with the analysis of Seripando’s sources, providing a new primary source to early modern historians. Keywords Girolamo Seripando – Vulgate – Council of Trent – John Driedo – San Giovanni a Carbonara Library 1 Introduction The aim of this article is to offer the very first transcription of Girolamo Seri- pando (1493–1563)’s unedited notes titled De Libris Sanctis, the only copy of 1 1 I thank a lot Prof. Dr. Violet Soen (ku Leuven) and Prof. Dr. Brad Gregory (University of Notre Dame), who helped me to date the manuscript that contains Seripando’s De Libris Sanctis. Moreover, thanks go to Ms Eliza Halling, who carefully checked the English of this article. © verlag ferdinand schöningh, 2019 | doi:10.30965/25890433-04802007Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 08:27:36PM via free access <UN> What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate 441 which is contained in a 17th century manuscript,1 still preserved in Naples at the National Library (Ms. -

Philip Melanchthon's Influence on the English Theological

PHILIP MELANCHTHON’S INFLUENCE ON ENGLISH THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT DURING THE EARLY ENGLISH REFORMATION By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö A dissertation submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology August 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö To the memory of my beloved husband, Tauno Pyykkö ii Abstract Philip Melanchthon’s Influence on English Theological Thought during the Early English Reformation By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö This study addresses the theological contribution to the English Reformation of Martin Luther’s friend and associate, Philip Melanchthon. The research conveys Melanchthon’s mediating influence in disputes between Reformation churches, in particular between the German churches and King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1539. The political background to those events is presented in detail, so that Melanchthon’s place in this history can be better understood. This is not a study of Melanchthon’s overall theology. In this work, I have shown how the Saxons and the conservative and reform-minded English considered matters of conscience and adiaphora. I explore the German and English unification discussions throughout the negotiations delineated in this dissertation, and what they respectively believed about the Church’s authority over these matters during a tumultuous time in European history. The main focus of this work is adiaphora, or those human traditions and rites that are not necessary to salvation, as noted in Melanchthon’s Confessio Augustana of 1530, which was translated into English during the Anglo-Lutheran negotiations in 1536. Melanchthon concluded that only rituals divided the Roman Church and the Protestants. -

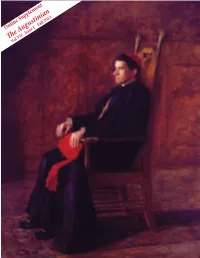

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St.