What Is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando's Notes on the Vulgate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Herunterladen

annuarium historiae conciliorum 48 (2016/2017) 440-462 brill.com/anhc What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate Dr. Antonio Gerace Fondazione per le Scienze Religiose Giovanni XXIII, Bologna, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven [email protected] Abstract Before the issue of the Insuper decree (1546), by means of which the Council Fathers declared the Vulgate to be the ‘authentic’ Bible for Catholic Church, Girolamo Seri- pando took few notes discussing the need of a threefold Bible, in Latin, Greek and He- brew, as he stressed in the General Congregation on 3 April 1546. Only Rongy (1927/28), Jedin (1937) and François/Gerace (2018) paid attention to this document, preserved at the National Library in Naples in a manuscript of the 17th century (Ms. Vind. Lat. 66, 123v–127v). In this article, the author offers the very first transcription of these notes together with the analysis of Seripando’s sources, providing a new primary source to early modern historians. Keywords Girolamo Seripando – Vulgate – Council of Trent – John Driedo – San Giovanni a Carbonara Library 1 Introduction The aim of this article is to offer the very first transcription of Girolamo Seri- pando (1493–1563)’s unedited notes titled De Libris Sanctis, the only copy of 1 1 I thank a lot Prof. Dr. Violet Soen (ku Leuven) and Prof. Dr. Brad Gregory (University of Notre Dame), who helped me to date the manuscript that contains Seripando’s De Libris Sanctis. Moreover, thanks go to Ms Eliza Halling, who carefully checked the English of this article. © verlag ferdinand schöningh, 2019 | doi:10.30965/25890433-04802007Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 01:00:28PM via free access <UN> What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate 441 which is contained in a 17th century manuscript,1 still preserved in Naples at the National Library (Ms. -

The Augustinian Vol VII

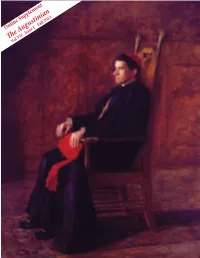

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

Forbidding Prayer in Italy and Spain: Censorship and Devotional Literature in the Sixteenth Century

Forbidding Prayer in Italy and Spain: Censorship and Devotional Literature in the Sixteenth Century. Current Issues and Future Research1 Giorgio Caravale Università di Roma Tre In the early 1490s, Girolamo Savonarola devoted two spiritual works to the theme of prayer. These were the Sermone dell’oratione and the Trattato in difen- sione e commendazione dell’orazione mentale (1492), which were followed two years later by the Espositione sul Pater noster (1494).2 Savonarola’s criticism tar- geted the rituals and the devotional practices of the laity in their following of the precepts of Rome. In these writings, Savonarola —anticipating by two dec- ades the invective of Querini and Giustiniani’s Libellum ad Leonem decimum3— lashed out against the mechanical recital of the Lord’s Prayer and the psalms, criticising voiced prayer as an end in itself, the symbol of sterile worship. In his view, a return to the inspiring and healthy principles of the early Roman Catho- lic Church was needed, since «God seeks from us interior knowledge without so much ceremony».4 External ceremony stimulated devotion, and constituted an intermediate passage in man’s search for God. Voiced prayer should be noth- ing more than a prelude to mental prayer. Its prime purpose was to create the conditions to enable man to lift «his mind to God so that divine love and holy contemplation are ignited».5 The moment the ascendant state is attained, words become not only useless but a hindrance to communication with God. 1. Translated by Margaret Greenhorn and Ju- 3. Mittarelli and Costadoni (1773: 612-719). -

Great Heroes of the Great Reformation

Great Heroes (and Antiheroes) of the Great Reformation Unit 6: The Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation Cardinal Gasparo St. Ignatius de Loyola Contarini (1483—1542) (1491—1556) Reformation and Divisions in the 16th-Century Roman Catholic Church • Protestant Reformers (Luther, Melanchthon, Zwingli, Calvin, Knox, Bucer, Bullinger, Cranmer, etc.) • Roman Catholic Evangelicals • Society of Jesus (Jesuits) • Council of Trent (1545—1547; 1551—1552; 1562—1563) • Papacy • Revival in the Religious Orders • New Spirituality (Mystics) • Extra-European Roman Catholic Expansion The Roman Catholic Evangelicals • Most, strongly affected by Augustine, mostly agreed with the Reformers’ doctrine of justification by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. • Disagreed with the Reformers’ break from allegiance to the papacy. • Mixed on Eucharist (transubstantiation vs. consubstantiation vs. spiritual presence vs. pure symbol) and other liturgical matters. • Agreed with Reformers’ pursuit of moral reform. • Worked 1521—1541 “to reform the Church of Rome from within, towards a more Biblical theology and practice, and thus to win back the Protestants into the one true Church.” (Needham) • Key figures: Johann von Staupitz, Gasparo Contarini, Juan de Valdes, Albert Pighius, Jacob Sadoleto, Gregorio Cortese, Reginald Pole, Johann Gropper, Girolamo Seripando, Giovanni Morone • 1537, issued Consilium de Emendanda Ecclesia (“Consultation on Reforming the Church”)—forthright condemnation of the moral state of the Roman Church; pope refused to publish it; leaked out; spread rapidly; Roman Inquisition placed it on “Index of Forbidden Books” Leading Roman Catholic Evangelicals • Johannes von Staupitz (1460—1524), Luther’s spiritual guide in Augustinian order; agreed with almost all Luther’s doctrine but couldn’t break with papacy; yet all Staupitz’s writings were placed on Rome’s “index of forbidden books” in 1563. -

Divided by Faith: the Protestant Doctrine of Justification and The

Divided by Faith: The Protestant Doctrine of Justification and the Confessionalization of Biblical Exegesis by David C. Fink Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date: Approved: David C. Steinmetz, Supervisor Elizabeth A. Clark Reinhard Hütter J. Warren Smith Sujin Pak Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Divided by Faith: The Protestant Doctrine of Justification and the Confessionalization of Biblical Exegesis by David C. Fink Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date: Approved: David C. Steinmetz, Supervisor Elizabeth A. Clark Reinhard Hütter J. Warren Smith Sujin Pak An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright 2010 by David C. Fink All rights reserved Abstract This dissertation lays the groundwork for a reevaluation of early Protestant understandings of salvation in the sixteenth century by tracing the emergence of the confessional formulation of the doctrine of justification by faith from the perspective of the history of biblical interpretation. In the Introduction, the author argues that the diversity of first-generation evangelical and Protestant teaching on justification has been widely underestimated. Through a close comparison of first- and second- generation confessional statements in the Reformation period, the author seeks to establish that consensus on this issue developed slowly over the course over a period of roughly thirty years, from the adoption of a common rhetoric of dissent aimed at critiquing the regnant Catholic orthopraxy of salvation in the 1520’s and 1530’s, to the emergence of a common theological culture in the 1540’s and beyond. -

113 Adam Patrick Robinson Thebehaviourofgiovannimorone,Likethatofreginaldpole

book reviews 113 Adam Patrick Robinson The Career of Cardinal Giovanni Morone (1509–1580). Between Council and Inquisition. Ashgate, Farnham 2012, xiv + 255 pp. ISBN 9781409417835. £65; US$124.95. The behaviour of Giovanni Morone, like that of Reginald Pole, puzzled both his contemporaries and later scholars. Strongly drawn at one point in their lives by the doctrine of justification by faith so elegantly formulated by Juan de Valdés, the two men remained loyal servants of the papacy and fell into line as soon as it was required of them. Were they, as both the Inquisition and the friends whom they abandoned implied, Protestants at heart who acted out of opportunism? Or had they always remained good Catholics for whom the Lutheran doctrine of salvation should be regarded as little more than an aberration? In the English-speaking world Cardinal Pole has been studied more than Cardinal Morone. Adam Patrick Robinson’s excellent The Career of Cardinal Giovanni Morone (1509–1580) is thus particularly welcome. Morone’s career was distinguished from the outset. After studying briefly at the university of Padua he took up residence as bishop of Modena early in 1533, was made a cardinal in 1535, and in 1536 was dispatched as papal nuncio to the court of Ferdinand of Austria. It was here that he first exhibited his skills as a diplomat and in these years that he started to press for an ecclesiastical council. Surprisingly enough for a man whose attitude was generally so conciliatory, he was always sceptical about the benefits of colloquies between Catholics and Protestants, and his misgivings were confirmed by his experiences at Hagenau and Worms in 1540, at Regensburg in 1541, and at Speyer in 1542. -

The Grammar of Justification: the Doctrines of Peter Martyr Vermigli and John Henry Newman and Their Ecumenical Implications

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Castaldo, Christopher A. (2015) The grammar of justification: the doctrines of Peter Martyr Vermigli and John Henry Newman and their ecumenical implications. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / London School of Theology. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/15772/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

The Italian Reformation Outside Italy Brill’S Studies in Intellectual History

The Italian Reformation outside Italy Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History General Editor Han van Ruler (Erasmus University Rotterdam) Founded by Arjo Vanderjagt Editorial Board C.S. Celenza (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore) M. Colish (Yale University) J.I. Israel (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) A. Koba (University of Tokyo) M. Mugnai (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa) W. Otten (University of Chicago) VOLUME 246 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsih The Italian Reformation outside Italy Francesco Pucci’s Heresy in Sixteenth-Century Europe By Giorgio Caravale LEIDEN | BOSTON The translation of this work has been funded by SEPS (Segretariato Europeo per le Pubblicazioni Scientifiche), Via Val d’Aposa 7, I-40123 Bologna, Italy—[email protected]—www.seps.it Cover illustration: ‘Disputation with Heretics’, detail of ‘The Militant Church’, a 14th-century fresco by Andrea Bonaiuti. Santa Maria Novella, Spanish Chapel, Florence, Italy. Courtesy Scala Archives, Firenze/ Fondo Edifici di Culto – Ministero dell’Interno. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Caravale, Giorgio, author. [Profeta disarmato. English] The Italian reformation outside Italy : Francesco Pucci’s heresy in sixteenth-century Europe / by Giorgio Caravale. pages cm. — (Brill’s studies in intellectual history, ISSN 0920-8607 ; volume 246) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24491-7 (hardback : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-24492-4 (e-book) 1. Pucci, Francesco, 1543–1597. 2. Christian heresies—History—16th century. 3. Europe—Intellectual life— 16th century. 4. Reformation. 5. Humanism—Italy. I. Title. CT1138.P83C3713 2015 945’.07—dc23 2015023721 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. -

A Reconsideration of Sin, Grace, and the Reformation Christopher Ocker

A Reconsideration of Sin, Grace, and the Reformation Christopher Ocker There is something fundamentally inaccurate about the way theology in the Reformation is routinely viewed: through a prism of debates that divided Catholics and Protestants at “anthropology,” “soteriology,” and other doctrines. To be sure, for over fifty years now it is customary for Catholic theologians to appreciate Martin Luther and John Calvin as constructive, even corrective voices, in the manner of Erwin Iserloh, Peter Manns, Hans Küng, Alexandre Ganoczy, David Tracy, Leonardo Boff, and Walter Kaspar; or to critique the effect and legacy of post-Reformation positions in the manner of Elizabeth Johnson. It has been customary for Protestant theologians to emphasize the Reformation’s late medieval theological background and to identify specific points of doctrinal continuity, in order to define more narrowly the moment of discontinuity, and perhaps, even, to find ways to overcome it, in the manner of Bernd Hamm, Dennis Janz, Karlfried Froehlich, Heiko Augustinus Oberman, Jane Dempsey Douglas, and Susan Schreiner. A crowning achievement of a generation of ecumenical scholarship is certainly the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification. Christian theologians today, or at least those who take historical theology seriously, including, by the way, evangelical ones, are simply more open to other Christian traditions than ever before. But there is still a problem, and it will not be overcome by one’s capacity to appreciate theologians across the fence who three generations ago one was supposed to fear or hate. There is a fundamental problem of perspective, namely that we think there was any significant difference (and the term ‘significant’ is operative) between Protestants and Catholics at all. -

Onofrio Panvinio Between Renaissance And

Libros The Invention of Papal History F ICHA BIBLIOGRÁFICA Stefan Bauer, The Invention of Papal History: Ono- frio Panvinio between Renaissance and Catholic Reform, Oxford, Oxford University Press, Oxford-Warburg Studies, 2020, 288 págs, ISBN 978-0-19-880700-1. William Stenhouse I Yeshiva University Stefan Bauer’s excellent new book examines the ecclesiastical history writing of On- ofrio Panvinio (1530-68) in the context of the confessionalisation of the period. Panvinio played a key role in two related developments in sixteenth-century historiography. He was a central figure in what we know as the antiquarian movement that flourished in Rome around 1550, when historians established new methods of interpreting and documenting primary sources, and he was one of the first to apply antiquarian methods to the history of the Chris- tian Church. He was also astonishingly productive: Bauer says, without overstatement, that «it would be hard to find another historian who had amassed such a large amount of ma- terial and written so many historical texts, on such a broad variety of subjects, by the age of thirty-eight» (p.2), Panvinio’s age at his death. Except for Jean-Louis Ferrary’s remarkably Revista de historiografía 34, 2020, pp. 421-427 EISSN: 2445-0057. https://doi.org/10.20318/revhisto.2020.5846 421 Libros detailed discussion of his work on pagan antiquities,1 Panvinio’s vast historical oeuvre has not attracted the attention that it deserves. Bauer adopts a three-pronged approach: he of- fers a new biography of Panvinio; he analyses in depth Panvinio’s account of elections to the papacy; and he places some of Panvinio’s other ecclesiastical history writing, including a study of St Peter, biographies of Renaissance popes, and an unpublished sweeping history of the Church, in the context of the period’s confessional approaches to history. -

ITALIA JUDAICA. Gli Ebrei Nello Stato Pontificio Fino Al Ghetto (1555)

PUBBLICAZIONI DEGLI ARCHIVI DI STATO SAGGI 47 \ ITALIA ]UDAICA Gli ebrei nello Stato pontificio fino al Ghetto (1555) Atti del VI Convegno internazionale Tel Aviv, 18-22 giugno 1995 Ilconvegno è stato organizzato dalMinistero per i beni cultnrali e ambientali, Ufficio MINISTERO PER I BENI CULTURALI E AMBIENTALI centrale per i beni archivistici, dall'Università di Tel Aviv e dall'Università ebraica di UFFICIO CENTRALE PER I BENI ARCHIVISTICI Gerusalemme. 1998 UFFICIO CENTRALE PER I BENI ARCHIVISTICI DIVISIONE STUDI E PUBBLICAZIONI COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Direttore generale per i beni archivistici: Salvatore Italia. COMMISSIONE MISTA ITALO·ISRAELIANA PER LA STORIA Direttore della divisione studi e pubblicazioni: Antonio Dentoni Litta. E LA CULTURA DEGLI EBREI IN ITALIA Comitato per le pubblicazioni: Salvatore Italia, presidente, Paola Carucci, Antonio Dentoni-Litta, Ferruccio Ferruzzi, Cosimo Damiano Fonseca, Guido Melis, Claudio VITTORE COLORNI - Università degli studi, Ferrara Pavone, Leopoldo Puncuh, Isabella Ricci, Antonio Romiti, Isidoro Soffietti, FAUSTO PUSCEDDU - Ministero per i beni culturali e ambientali, Roma Giuseppe Talamo. Lucia Fauci Moro, segretaria. FAUSTO PARENTE - Università degli Studi, Roma, Tar Vergata SHLOMO SIMONSOHN - Te! Aviv University PROGR AMMA Luned� 18 giugno 20.00 Seduta di apertura. Indirizzi di saluto .. Ricevimento Luned� 19 giugno 9.00-12.30 Sh. Simonsohn (Università di Te! Aviv) Gli ebrei a Roma e nello Stato Pontificio © 1998 Ministero per i beni culturali e ambientali Ufficio centrale per i beni archivistici Y. Shatzmiller (Duke University, North Carolina) ISBN 88-7125-148-2 Monarchia papale nel medio evo: il concetto ebraico A.M. Racheli (Università di Roma) Vendita: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato-Libreria dello Stato Gli insediamenti ebraici a Roma prima del ghetto Piazza Verdi 10 - 00198 Roma Dibattito Stampato nel mese di maggio 1998 da Fratelli Palombi Editori· Roma Italia Judaica VI 7 6 Programma M. -

Convent Spaces and Religious Women: a Look at a Seventeenth-Century Dichotomy

Convent Spaces and Religious Women: A Look at a Seventeenth-Century Dichotomy A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Elizabeth A. Jones March 2008 2 © 2008 Elizabeth A. Jones All Rights Reserved 3 This dissertation titled Convent Spaces and Religious Women: A Look at a Seventeenth-Century Dichotomy by ELIZABETH A. JONES has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Charles S. Buchanan Associate Professor of the School of Interdisciplinary Arts Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 4 ABSTRACT JONES, ELIZABETH A., Ph.D, March 2008, Interdisciplinary Arts Convent Spaces and Religious Women: A Look at a Seventeenth-Century Dichotomy (204 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Charles S. Buchanan Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori is a seventeenth-century Roman convent that was built between 1642-1667 and was founded by a woman, Duchess Camilla Virginia Savelli Farnese, the wife of Duke Pietro Farnese. It remains as a paradigm that seventeenth-century female monasteries were spaces of freedom and peace for religious women, where the nuns exerted their agency (that is, the power to discern and to choose). They were not penitentiaries with inmates, as some have considered them to be. Camilla's agency created a place in which women could seek the ancient Christian pursuit of purity of heart and experience spiritual perfection. The women at S.M. dei Sette Dolori were not unique. They were following in the footsteps of many women before them as far back as Mary, the sister of Lazarus whom Jesus raised from the dead.