Sarpi's Use of Language in Making History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting Program

e Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting Program Philadelphia April 02 - 04, 2020 Table of Contents Links to Program Times and Sessions ursday at 6:00 pm RSA Awards Ceremony Friday at 6:00 pm CANCELLED: Josephine Waters Bennett Lecture Saturday at 6:30 pm RSA 2020 Philadelphia Closing Reception ursday at 11:00 am RSA Board of Directors Meeting ursday at 4:00 pm Cervantes Society of America Business Meeting and Society for Renaissance Studies (UK) Annual Lecture Annual Lecture Friday at 12:45 pm RSA Council Meeting Friday at 4:00 pm Margaret Mann Phillips Lecture Saturday at 2:00 pm e RSA High School Teaching Program Saturday at 4:00 pm American Cusanus Society Lecture Society for the Study of Early Modern Women and Gender Annual Lecture and Business Meeting Saturday at 5:30 pm Society for the Study of Early Modern Women and Gender Reception Saturday at 5:45 pm RSA Member Meeting ursday at 9:00 am (More an) irteen Ways of Looking at a Preacher: Netherlandish Printmaking Before Aux uatre Vents: Approaches to Early Modern Spanish Preaching Professionalism in the Graphic Arts, ca. 1500–50 CANCELLED: Barberiniana – Aspects of the Barberini New Perspectives on Italian Art I Reign (1623–44): A New Renaissance in Baroue Rome New Technologies and Renaissance Studies I: Trace I and Pattern CANCELLED: French Tragedy and the Wars of Pico, Machiavelli, and Ficino: Metaphysics, Ethics, and Religion eology CANCELLED: Impressed upon the Imagination: Reassessing Lucrezia Marinella's Oeuvre I Recreating Manuscript Cultures in the Age of Print Reconsidering -

Hunting the White Elephant. When and How Did Galileo

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 97 (1998) Jürgen Renn, Peter Damerow, Simone Rieger, and Michele Camerota Hunting the White Elephant When and how did Galileo discover the law of fall? ISSN 0948-9444 1 HUNTING THE WHITE ELEPHANT WHEN AND HOW DID GALILEO DISCOVER THE LAW OF FALL? Jürgen Renn, Peter Damerow, Simone Rieger, and Michele Camerota Mark Twain tells the story of a white elephant, a present of the king of Siam to Queen Victoria of England, who got somehow lost in New York on its way to England. An impressive army of highly qualified detectives swarmed out over the whole country to search for the lost treasure. And after short time an abundance of optimistic reports with precise observations were returned from the detectives giving evidence that the elephant must have been shortly before at that very place each detective had chosen for his investigations. Although no elephant could ever have been strolling around at the same time at such different places of a vast area and in spite of the fact that the elephant, wounded by a bullet, was lying dead the whole time in the cellar of the police headquarters, the detectives were highly praised by the public for their professional and effective execution of the task. (The Stolen White Elephant, Boston 1882) THE ARGUMENT In spite of having been the subject of more than a century of historical research, the question of when and how Galileo made his major discoveries is still answered insufficiently only. It is mostly assumed that he must have found the law of fall around the year 1604 and that only sev- 1 This paper makes use of the work of research projects of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, some pursued jointly with the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, the Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, and the Istituto Nazionale die Fisica Nucleare in Florence. -

PDF Herunterladen

annuarium historiae conciliorum 48 (2016/2017) 440-462 brill.com/anhc What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate Dr. Antonio Gerace Fondazione per le Scienze Religiose Giovanni XXIII, Bologna, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven [email protected] Abstract Before the issue of the Insuper decree (1546), by means of which the Council Fathers declared the Vulgate to be the ‘authentic’ Bible for Catholic Church, Girolamo Seri- pando took few notes discussing the need of a threefold Bible, in Latin, Greek and He- brew, as he stressed in the General Congregation on 3 April 1546. Only Rongy (1927/28), Jedin (1937) and François/Gerace (2018) paid attention to this document, preserved at the National Library in Naples in a manuscript of the 17th century (Ms. Vind. Lat. 66, 123v–127v). In this article, the author offers the very first transcription of these notes together with the analysis of Seripando’s sources, providing a new primary source to early modern historians. Keywords Girolamo Seripando – Vulgate – Council of Trent – John Driedo – San Giovanni a Carbonara Library 1 Introduction The aim of this article is to offer the very first transcription of Girolamo Seri- pando (1493–1563)’s unedited notes titled De Libris Sanctis, the only copy of 1 1 I thank a lot Prof. Dr. Violet Soen (ku Leuven) and Prof. Dr. Brad Gregory (University of Notre Dame), who helped me to date the manuscript that contains Seripando’s De Libris Sanctis. Moreover, thanks go to Ms Eliza Halling, who carefully checked the English of this article. © verlag ferdinand schöningh, 2019 | doi:10.30965/25890433-04802007Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 01:00:28PM via free access <UN> What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate 441 which is contained in a 17th century manuscript,1 still preserved in Naples at the National Library (Ms. -

The Contribution of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini (1850-1917) to Catholic Educational Practice in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

The Contribution of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini (1850-1917) to Catholic Educational Practice in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Maria Patricia Williams Ph D Thesis University College London Institute of Education 1 I, Maria Patricia Williams confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract My thesis evaluates the educational practice of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini (1850-1917). Cabrini, a schoolteacher from Lombardy, founded the Institute of Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (MSC) in Codogno, Italy in 1880. When she died, a United States citizen in Chicago, USA, she had established 70 houses in Europe and the Americas. One thousand women had joined the MSC. Her priority was to work with some of the estimated thirteen million Italians who emigrated between 1880 and 1915. The literature review considers the relatively little work in the history of education on Catholic educational practice. The research addresses three questions: 1. How did Mother Cabrini understand Catholic educational practice? 2. How can Mother Cabrini’s understanding of Catholic educational practice be seen in the work of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? 3. How far did Mother Cabrini develop a coherent approach to Catholic educational practice? A multiple case study approach is used, focussing on the educational practice of Cabrini and the MSC in Rome, London and New Orleans, within the transnational context of their Institute. -

Europa E Italia. Studi in Onore Di Giorgio Chittolini

21 CORE VENICE AND THE VENETO Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Reti Medievali Open Archive DURING THE RENAISSANCE THE LEGACY OF BENJAMIN KOHL Edited by Michael Knapton, John E. Law, Alison A. Smith thE LEgAcy of BEnJAMin KohL BEnJAMin of LEgAcy thE rEnAiSSAncE thE during VEnEto thE And VEnicE Smith A. Alison Law, E. John Knapton, Michael by Edited Benjamin G. Kohl (1938-2010) taught at Vassar College from 1966 till his retirement as Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities in 2001. His doctoral research at The Johns Hopkins University was directed by VEnicE And thE VEnEto Frederic C. Lane, and his principal historical interests focused on northern Italy during the Renaissance, especially on Padua and Venice. during thE rEnAiSSAncE His scholarly production includes the volumes Padua under the Carrara, 1318-1405 (1998), and Culture and Politics in Early Renaissance Padua thE LEgAcy of BEnJAMin KohL (2001), and the online database The Rulers of Venice, 1332-1524 (2009). The database is eloquent testimony of his priority attention to historical sources and to their accessibility, and also of his enthusiasm for collaboration and sharing among scholars. Michael Knapton teaches history at Udine University. Starting from Padua in the fifteenth century, his research interests have expanded towards more general coverage of Venetian history c. 1300-1797, though focusing primarily on the Terraferma state. John E. Law teaches history at Swansea University, and has also long served the Society for Renaissance Studies. Research on fifteenth- century Verona was the first step towards broad scholarly investigation of Renaissance Italy, including its historiography. -

Rethinking Savoldo's Magdalenes

Rethinking Savoldo’s Magdalenes: A “Muddle of the Maries”?1 Charlotte Nichols The luminously veiled women in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s four Magdalene paintings—one of which resides at the Getty Museum—have consistently been identified by scholars as Mary Magdalene near Christ’s tomb on Easter morning. Yet these physically and emotionally self- contained figures are atypical representations of her in the early Cinquecento, when she is most often seen either as an exuberant observer of the Resurrection in scenes of the Noli me tangere or as a worldly penitent in half-length. A reconsideration of the pictures in connection with myriad early Christian, Byzantine, and Italian accounts of the Passion and devotional imagery suggests that Savoldo responded in an inventive way to a millennium-old discussion about the roles of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene as the first witnesses of the risen Christ. The design, color, and positioning of the veil, which dominates the painted surface of the respective Magdalenes, encode layers of meaning explicated by textual and visual comparison; taken together they allow an alternate Marian interpretation of the presumed Magdalene figure’s biblical identity. At the expense of iconic clarity, the painter whom Giorgio Vasari described as “capriccioso e sofistico” appears to have created a multivalent image precisely in order to communicate the conflicting accounts in sacred and hagiographic texts, as well as the intellectual appeal of deliberately ambiguous, at times aporetic subject matter to northern Italian patrons in the sixteenth century.2 The Magdalenes: description, provenance, and subject The format of Savoldo’s Magdalenes is arresting, dominated by a silken waterfall of fabric that communicates both protective enclosure and luxuriant tactility (Figs. -

Thomas Hobbes: Fascist Exponent Of

Thomas Hobbes Click hereforFullIssueofFidelioVolume5,Number1,Spring1996 k r k o r o Y Y w e w e N , N n , o n i t o i c t e c l l e l o l o C C r e r g e n g a n r a r G G e h e h T T Fascist Exponent of © 1996 Schiller Institute, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction inwhole orinpart without permission strictly prohibited. Enlightenment Science by Brian Lantz n his May 10, 1982 speech to the British Foreign Ser- the horrors of Cambodia, Somalia, Rwanda, and Bosnia. vice assembled at the Royal Institute of International The literally fascist legislative agenda of Conservative IAffairs’ Chatham House, Henry Kissinger lauded Revolutionaries Newt Gingrich and Phil Gramm, under the “Hobbesian” premise of British foreign policy. That the sponsorship of various Mont Pelerin Society-connect- Kissinger was correct in identifying the axiomatics of ed thinktanks, underscores the significance of “Sir” British foreign policy as “Hobbesian,” should alert the Kissinger’s Hobbesian remark for domestic politics with- reader to the significance of the doctrines of Thomas in the United States itself. Hobbes (1588-1679), to the events unfolding now, three Like his homosexual lover Francis Bacon and fellow hundred and fifty years later, as Current History. British empiricist John Locke, Thomas Hobbes was Over the past century, for geopolitical purposes, the deployed by the then-Venice-centered oligarchy against British oligarchy has orchestrated a true Hobbesian “war __________ of each against all,” bringing about two world wars and Thomas Hobbes (center), Paolo Sarpi (left), Galileo Galilei (right). -

008-70 509.Pdf

in the Preaching of the Word of Goel. 509 our :M:aster's messengers, of bearing it in our ministration in this needing world ! His last word to His Church assemblecl in her representa,tives was, "Ye shall be witnesses of Me." And time only intensifies the need and power of obedience to that royal order. How, in our preaching, under the blessing of the Holy Spirit, shall we best find out the soul, and win it for our beloved Lord, and build it up in Him 1 On the one hand, by an unwearied affirmation, thoughtful, loving, con fident, of the eternal facts; on the other, by snch a presenta tion of them as shall let all men see that they are facts to us. ---=~--- ART. II.-FR.A PAOLO SARPI. HE Rev. Alexander Robertson has rnceivecl a letter of T thanks from the King of Italy, through the governor of the Royal Houseb old, for his "Life of Paolo Sarpi," and he has also been honoured with the degree of Doctor bestowec1 upon him in Scotland for bis literary labours. These acts of grace and courtesy are a strong testimony to the value of the work before us,1 while the first witnesses also to the liberality of the Italian Court. It was high time that Sarpi's Life should be issued in a trustworthy form, drawn from original sources which have been too much overlooked. Sarpi had the honour of being regarded as a dangerous antagonist by that section of the Roman Church which, while it is specially represented by the Jesuits, is far from confined to the members of that society. -

Norberto Gramaccini Petrucci, Manutius Und Campagnola Die Medialisierung Der Künste Um 1500

Norberto Gramaccini Petrucci, Manutius und Campagnola Die Medialisierungder Künste um 1500 Die Jahre um 1500 waren für die Medialisierung der Künste und Wissenschaften von entscheidender Bedeutung.1 Am 15.Mai 1501 brachte in Venedig der aus Fossombrone gebürtige Musikdrucker Ottaviano dei Petrucci (1466–1539) mitseinemmusikalischen BeraterPetrusCastellanus das Harmonicemusices OdhecatonA(RISM 15011)heraus: Es ist das erste im Typendruckverfahren hergestellte Buch in mehrstimmigen Mensuralnoten, enthaltend 100drei- und vierstimmige Chansons der bekanntesten zeitgenössischen Komponisten –die meisten Franzosen und Flamen.2 Bereits 1498 hatte Petrucci beim veneziani- schen Senat ein Gesuch gestellt, das ihm als Erfnder ein Monopol für die Dauer von 20 Jahren zusichern sollte: »… chome aprimo Inventore che niuno altro nel dominio de Vostra Signoria possi stampare Canto fgurado …per anni vinti«.3 Dem Erstling folgten gleichgeartete Publikationen (Canti B, Canti C), die ei- nen Hinweis liefern, dass Petruccis vorrangiges Ziel in den ersten Jahren sei- ner Herausgebertätigkeit (bis 1504)darin bestand, nicht die sakrale, sondern 1Hans Blumenberg, Die Lesbarkeit der Welt,Frankfurt 1983;David McKitterick, Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450–1830,Cambridge 2004,S.109. 2Helen Hewitt und Isabel Pope, Petrucci. Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A,New York 1978. Das Datum 15/V/1501geht aus der Widmung an Girolamo Donato hervor. Für eine andere Datierung, David Fallows, »Petrucci’s Canti Volumes: Scope and Repertory«, in: Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis 25: Musik –Druck –Musikdruck. 500Jahre Ottaviano Petrucci (2001), S.39–52: S.41.ZuCastellanus,dem »magistercapelle«der Kirche SS.Giovanni ePaolo, den die Zeitgenossen als »arte musice monarcha« bezeichneten, Bonnie J. Blackburn, »Petrucci’s Venetian Editor: Petrus Castellanus and His Musical Garden«, in: Musica Disciplina 40 (1995), S.15–41: S.25.Zuden späten Quellen, die Petrucci auch als Besitzer mehrerer Papiermühlen ausweisen, Teresa M. -

What Is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando's Notes on the Vulgate

annuarium historiae conciliorum 48 (2016/2017) 440-462 brill.com/anhc What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate Dr. Antonio Gerace Fondazione per le Scienze Religiose Giovanni XXIII, Bologna, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven [email protected] Abstract Before the issue of the Insuper decree (1546), by means of which the Council Fathers declared the Vulgate to be the ‘authentic’ Bible for Catholic Church, Girolamo Seri- pando took few notes discussing the need of a threefold Bible, in Latin, Greek and He- brew, as he stressed in the General Congregation on 3 April 1546. Only Rongy (1927/28), Jedin (1937) and François/Gerace (2018) paid attention to this document, preserved at the National Library in Naples in a manuscript of the 17th century (Ms. Vind. Lat. 66, 123v–127v). In this article, the author offers the very first transcription of these notes together with the analysis of Seripando’s sources, providing a new primary source to early modern historians. Keywords Girolamo Seripando – Vulgate – Council of Trent – John Driedo – San Giovanni a Carbonara Library 1 Introduction The aim of this article is to offer the very first transcription of Girolamo Seri- pando (1493–1563)’s unedited notes titled De Libris Sanctis, the only copy of 1 1 I thank a lot Prof. Dr. Violet Soen (ku Leuven) and Prof. Dr. Brad Gregory (University of Notre Dame), who helped me to date the manuscript that contains Seripando’s De Libris Sanctis. Moreover, thanks go to Ms Eliza Halling, who carefully checked the English of this article. © verlag ferdinand schöningh, 2019 | doi:10.30965/25890433-04802007Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 08:27:36PM via free access <UN> What is the Vulgate? Girolamo Seripando’s notes on the Vulgate 441 which is contained in a 17th century manuscript,1 still preserved in Naples at the National Library (Ms. -

Paolo Sarpi, the Absolutist State and the Territoriality of the Adriatic Sea

Erasmo Castellani Paolo Sarpi, the Absolutist State and the Territoriality of the Adriatic Sea The years between the second half of the sixteenth century and the first few decades of the seventeenth constituted a period of general reconfiguration throughout the Mediterranean. The hegemonic position held by Venice from centuries on the Adriatic Sea, or “the Venetian Gulf”, as it was called, started to be disputed persistently by other powers. The Dominio da mar, the Venetian territories in the Mediterranean – and Venice itself – were not living their best times: Venice was still recovering from the terrible wounds inflicted by the Ottoman Empire in the 1570s, and trying to solve the tragic loss of Cyprus, extremely significant for the Republic not only in terms of resources and men, but also for its political value and reputation. The Turks, who had represented the main threat for the Venetian maritime territories from the end of the fourteenth century, were worn-out too by the intense and truculent decade, and after 1573 (the so-called war of Cyprus), did not engage in seafaring wars with Venice until 1645 with the Cretean wars. The Uskok corsairs, who enjoyed the support of the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, officially to fight the Turks, tormented Venice and its territories on the Dalmatian coast between the 1580s and 1610s, raiding villages, cargos and, in general, making the Adriatic routes less and less secure. The Uskoks, as the Barbary corsairs, represented not only a harmful presence on the sea, but also an economic and political threat for Venice: corsairs activities in fact offered to the Venetian subjects on the 1 Dalmatian coast opportunities to engage in small commercial enterprises without being submitted to the Serenissima’s regulations. -

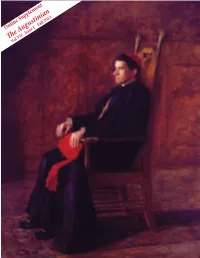

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St.