Men, Cohesion, and Battle : the Inniskilling Regiment at Waterloo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

British Reaction to the Sepoy Mutiny, 1857-1858 Approved

BRITISH REACTION TO THE SEPOY MUTINY, 1857-1858 APPROVED: Major /Professor mor Frotessar of History Dean' ot the GraduatGradua' e ScHooT* BRITISH REACTION TO THE SEPOY MUTINY, 1857-185S THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Samuel Shafeeq Denton, Texas August, 1970 PREFACE English and Indian historians have devoted considerable research and analysis to the genesis of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 but have ignored contemporary British reaction to it, a neglect which this study attempts to satisfy. After the initial, spontaneous, condemnation of Sepoy atrocities, Queen Victoria, her Parliament, and subjects took a more rational and constructive attitude toward the insurrection in India, which stemmed primarily from British interference in Indian religious and social customs, symbolized by the cartridge issue. Englishmen demanded reform, and Parliament-- at once anxious to please the electorate and to preserve the valuable colony of India--complied within a year, although the Commons defeated the first two Indian bills, because of the interposition of other foreign and domestic problems. But John Bright, Lord Edward Stanley, William Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli, and their friends joined forces to pass the third Indian bill, which became law on August 2, 1858. For this study, the most useful primary sources are Parliamentary Debates. Journals of the House of Commons and Lords, British and Foreign State' Papers, English Historical Queen Victoria's Letters , and the Annual' Re'g'i'st'er. Of the few secondary works which focus on British reac- tion to the Sepoy Mutiny, Anthony Wood's Nineteenth Centirr/ Britain, 1815-1914 gives a good account of British politics after the Mutiny. -

October 29,1867

— ill gy* a||H|||HW|wu?!^| • 7 PORTLAND, "TUESDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 29, 1867. ~ [ 1HK J'OKTLAND DAILY PllKSS Is g published HE'ISSESS CAICOS. v. rv day, (.Sunday excepted.' hi *N.i. 1 Printers’ imillMNC'l. KJ’noVAl.f, fcve.liange, Kicbangc Stieet, Portland, “roan fy—arm.” Bible ouil important pn.-itori be l«dd at the N. A. KOSTKK, PltOF fURTUK. tl until E l.. DAILY PRESS. Tiie farewell speech of Sir bead of that cMlublij-liinctif. Mr. FIVKETT, John Michel a Newcomb a«- I iCicaa KiirHt Dollars a veal ill a D ane? JORDAN & RANDALL n K M O V zV L of which we last xe.-tH Life Insurance* summary printed week, is at- ih it what the Observatory really accom- :bo and HAVING REMOVED TO TIIE POIM'LAND. 4 111*: MAlNK ST A'I iCJ’ltfcSS. m |uib.‘ijdmdaf Druggist Apothecary, J.4M/.'s’ /■' tracting very general attention and comment. pli.bed for tirienre w;u»dt:e not to Maury, but * nue Thor nuii’tiina # Wl • >4,>ir* ANIt IriLLEK, plarv1 rery ,jh'. »J UKAI.KR IN M. B. PAGE The real News t*> twool hit> in H*lvHii« e. Store No. Middle Mon* says: MaistanU, Scare Cook Walker, i'?:iml.ly 14S St., COUNSEi.i.uR AT the hnylish American Hoods, lo call the attention of the LAW, Tuesday titst practical astronomer in the I' ii III Fancy I i'ltuio public, to ilie 0;tober 1837. the water country, it % IT.s <»r UIVMiriUKiJ.—»»li. *pA* t\lll Hindi,) Hn l Morning, 29, “Fortify—anil—o|»en great route Ao. -

SPANISH FORK PAGES 1-20.Indd

November 14 - 20, 2008 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, November 14 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey b News (N) b CBS Evening News (N) b Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Threshold” The Price Is Right Salutes the NUMB3RS “Charlie Don’t Surf” News (N) b (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight (N) b Troops (N) b (N) b Letterman (N) KJZZ 3 High School Football The Insider Frasier Friends Friends Fortune Jeopardy! Dr. Phil b News (N) Sports News Scrubs Scrubs Entertain The Insider The Ellen DeGeneres Show Ac- News (N) World News- News (N) Access Holly- Supernanny “Howat Family” (N) Super-Manny (N) b 20/20 b News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4 tor Nathan Lane. (N) Gibson wood (N) b line (N) wood (N) (N) b News (N) b News (N) b News (N) b NBC Nightly News (N) b News (N) b Deal or No Deal A teacher returns Crusoe “Hour 6 -- Long Pig” (N) Lipstick Jungle (N) b News (N) b (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night KSL 5 News (N) to finish her game. b Jay Leno (N) b TBS 6 Raymond Friends Seinfeld Seinfeld ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (G, ’39) Judy Garland. (8:10) ‘Shrek’ (’01) Voices of Mike Myers. -

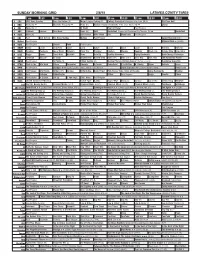

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction. -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

Waterloo 200

WATERLOO 200 THE OFFICIAL SOUVENIR PUBLICATION FOR THE BICENTENARY COMMEMORATIONS Edited by Robert McCall With an introduction by Major General Sir Evelyn Webb-Carter KCVO OBE DL £6.951 TheThe 200th Battle Anniversary of Issue Waterloo Date: 8th May 2015 The Battle of Waterloo The Isle of Man Post Offi ce is pleased 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man to celebrate this most signifi cant historical landmark MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 in collaboration with 75p 75p Waterloo 200. Isle of Man Isle of Man MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 SET OF 8 STAMPS MINT 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH31 – £6.60 PRESENTATION PACK TH41 – £7.35 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FIRST DAY COVER 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH91 – £7.30 SHEET SET MINT TH66 – £26.40 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FOLDER “The whole art of war consists of guessing at what is on the other side of the hill” TH43 – £30.00 Field Marshal His Grace The Duke of Wellington View the full collection on our website: www. iomstamps.com Isle of Man Stamps & Coins GUARANTEE OF SATISFACTION - If you are not 100% PO Box 10M, IOM Post Offi ce satisfi ed with the product, you can return items for exchange Douglas, Isle of Man IM99 1PB or a complete refund up to 30 days from the date of invoice. -

The Scottish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1968 The cottS ish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian War Nelson Orion Westphal Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Westphal, Nelson Orion, "The cS ottish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian War" (1968). Masters Theses. 4157. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4157 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #3 To: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. Subject: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced -

J\S-Aacj\ Cwton "Wallop., $ Bl Sari Of1{Ports Matd/I

:>- S' Ui-cfAarria, .tffzatirU&r- J\s-aacj\ cwton "Wallop., $ bL Sari of1 {Ports matd/i y^CiJixtkcr- ph JC. THE WALLOP FAMILY y4nd Their Ancestry By VERNON JAMES WATNEY nATF MICROFILMED iTEld #_fe - PROJECT and G. S ROLL * CALL # Kjyb&iDey- , ' VOL. 1 WALLOP — COLE 1/7 OXFORD PRINTED BY JOHN JOHNSON Printer to the University 1928 GENEALOGirA! DEPARTMENT CHURCH ••.;••• P-. .go CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Omnes, si ad originem primam revocantur, a dis sunt. SENECA, Epist. xliv. One hundred copies of this work have been printed. PREFACE '•"^AN these bones live ? . and the breath came into them, and they ^-^ lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.' The question, that was asked in Ezekiel's vision, seems to have been answered satisfactorily ; but it is no easy matter to breathe life into the dry bones of more than a thousand pedigrees : for not many of us are interested in the genealogies of others ; though indeed to those few such an interest is a living thing. Several of the following pedigrees are to be found among the most ancient of authenticated genealogical records : almost all of them have been derived from accepted and standard works ; and the most modern authorities have been consulted ; while many pedigrees, that seemed to be doubtful, have been omitted. Their special interest is to be found in the fact that (with the exception of some of those whose names are recorded in the Wallop pedigree, including Sir John Wallop, K.G., who ' walloped' the French in 1515) every person, whose lineage is shown, is a direct (not a collateral) ancestor of a family, whose continuous descent can be traced since the thirteenth century, and whose name is identical with that part of England in which its members have held land for more than seven hundred and fifty years. -

Wellington's Supply System During Tk Pcninsular War, 1 809-1 8 14. Tina

Wellington's Supply System during tk Pcninsular War, 1809-1 8 14. Tina M. McLauchh History Department McGill University, Md Augusî 1997 A thesis submitted to the Facule of Graduate Studia and Research in partial fulnllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Copyright O 1997 by Tina M. McLauchlan. National Library BiMiaWque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services senfices bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington OttawaON KtAON4 OtlawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licefice non exclusive Licence dowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du danada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seii reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microforni, vendre des copies de cette @se SOUS paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège thèse- thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits scibstantiels may be printed or otheniise de celle-ci ne doivent être @primés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits SMson permission. autorisation. Much of the sufeess of the Allied Peninsular Amy was due to the effectiveness of Wellington's supply systan. The ability of Welhgton to keep his army supplied presented him with an enormous advantage over the French This paper examines the role logistics played in deciding the ouiforne of the war in the Penionila as weli as detailing the needs of the t~oops.The primary focus of this paper is the procurement, transport, and payment of supplies for the use of the Allied Amy during the Penuwlar War.