Readers-Experiences-Of-Braille-In-An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New International Manual of Braille Music Notation by the Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union

1 New International Manual Of Braille Music Notation by The Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union Compiled by Bettye Krolick ISBN 90 9009269 2 1996 2 Contents Preface................................................................................ 6 Official Delegates to the Saanen Conference: February 23-29, 1992 .................................................... 8 Compiler’s Notes ............................................................... 9 Part One: General Signs .......................................... 11 Purpose and General Principles ..................................... 11 I. Basic Signs ................................................................... 13 A. Notes and Rests ........................................................ 13 B. Octave Marks ............................................................. 16 II. Clefs .............................................................................. 19 III. Accidentals, Key & Time Signatures ......................... 22 A. Accidentals ................................................................ 22 B. Key & Time Signatures .............................................. 22 IV. Rhythmic Groups ....................................................... 25 V. Chords .......................................................................... 30 A. Intervals ..................................................................... 30 B. In-accords .................................................................. 34 C. Moving-notes ............................................................ -

Braille Research Newsletter #5, July 1977

/' BRAILLE RESEARCH NEWSLETTER (Braille Automation Newsletter) "pm No. 5, July 1977 edited by J.M. Gill and L.L. Clark WW| yWf awj- Warwick Research Unit for American Foundation for the Blind the Blind University of Warwick 15 West 16th Street Coventry CV4 7AL New York 10011 England U.S.A. •**SHf| Contents Page Editorial 2 Automatic Translation by Computer of Music 5 Notation to Braille by J.B. Humphreys Braille Books from Compositors ' Tapes 13 by C„ Brosamle A Note on Hybrid Braille Production 19 by P.W.F. Coleman The Expansion of Braille Production in Sweden 26 by B. Hampshire and S. Becker Plate Embossing Device by P.D. Gibbons and 32 E.L. Ost Braille Systems by J«E. Sullivan 35 An Analysis of Braille Contractions by 50 J.M. Gill and J.B. Humphreys Using Redundancy for the Syntactic Analysis of 58 Natural Language: Application to the Automatic Correction of French Text by J. Courtin TOBIA 60 Congress in Toronto 60 Recent Publications and Reports 61 Address List 63 - 2 - Editorial With this issue, the Braille Automation Newsletter changes its name to Braille Research Newsletter. We shall continue to use the former heading as a sub-heading for the purpose of continuity in libraries and to identify ourselves as to origin. The reason for a name change is in fact a recognition that the automatic generation of braille depends, from the point of view of optimal design, upon a consideration of the changes that eventually will occur in the braille code as a natural result of continual review by braille authorities to keep the code up-to-date. -

Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick

JBN 0-8444-0 9 C D E F G Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Federation of the Blind (NFB) http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofbraiOObett LIBRARY IOWA DEPARTMENT FOR THE BLIND 524 Fourth Street Des Moines, Iowa 50309-2364 Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20542 1979 MT. PLEASANT HIGH SCHOOL LIBRARY Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Krolick, Bettye. Dictionary of braille music signs. At head of title: National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress. Bibliography: p. 182-188 Includes index. 1. Braille music-notation. I. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. II. Title. MT38.K76 78L.24 78-21301 ISBN 0-8444-0277-X . TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix HISTORY OF THE BRAILLE MUSIC CODE ... xi HOW TO LOCATE A DEFINITION xviii DICTIONARY OF SIGNS (A sign that contains two or more cells is listed under its first character.) . 1 •* 1 •• 16 • • •• 3 •• 17 •> 6 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 9 •• 19 •• •• 9 •• 19 • • •• 10 •• 20 • • •• 12 •• 20 •• 14 •• 20 •• •• 14 •• 22 • • •• •• 15 • • 27 •• •• •« •• 15 • • 29 •• • • •« 16 30 •• •• 16 • • 30 30 i: 46 ?: 31 11 47 r. 31 ;: 48 •: 31 i? 58 ?: 31 i; 78 ::' 34 :: 79 a 34 ;: si 35 ;? 86 37 ;: 90 39 ':• 96 40 ;: 102 43 i: 105 45 ;: 113 46 FORMATS FOR BRAILLE MUSIC 122 Format Identification Chart 125 Music in Parallels -

Guide to Independent Living for Older Individuals Who Are Blind Or Visually Impaired

Texas Workforce Solutions-Vocational Rehabilitation Services Guide to Independent Living for Older Individuals Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO INDEPENDENT LIVING ADJUSTMENT TO BLINDNESS • Common Eye Diseases — 4 • Definition of Terms — 7 • Questions to Ask your Doctor — 9 • Low Vision Information — 11 • Emotional Aspects of Vision Loss — 18 • Diabetes Information — 28 IDEAS & TIPS FOR PEOPLE WITH VISION LOSS • Organizing & Labeling — 36 • Food & Kitchen Tips — 38 • Lighting — 51 • Furnishings — 55 • Keys — 57 • Laundry & Sewing — 57 • Cleaning — 59 • Bathroom — 60 • Personal Management — 61 • Shopping — 66 • Finances — 71 • Safety & Security — 74 • Using Your Remaining Senses — 76 TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES FOR BEING INDEPENDENT • Alternative Techniques — 79 TRAVEL & TRANSPORTATION • Community Transportation — 83 • Orientation & Mobility Information — 84 • Guiding Techniques — 88 COMMUNICATION • Using the Telephone — 90 • Reading & Writing — 92 • Assistive Technology — 104 SUPPORT SYSTEMS • Consumer Organizations — 112 QUALITY OF LIFE • Recreation — 116 • Adaptive Aids Catalogues — 122 • Self-Advocacy — 124 • Support & Assistance — 125 INDEPENDENT LIVING RESOURCES — 128 Texas Workforce Solutions comprises the Texas Workforce Commission, 28 local workforce development boards and our service-providing partners. Together we provide workforce, education, training and support services, including vocational rehabilitation assistance for the people of Texas. Welcome to the world of independent living at Texas Workforce Solutions-Vocational Rehabilitation Services (TWS-VRS). You received this guide because you may have been referred to our Independent Living Services for Older Individuals Who Are Blind (ILS-OIB) program by a family member, doctor, rehabilitation counselor or other professional. Introduction to Independent Living — 1 If this is the first time you’ve heard of TWS- VRS, a little background information may be helpful. -

Unified English Braille Webinar Presentation

Unified English Braille: A Place to Start Webinar • UEB Ain't Hard to Do by Mark Brady a NYC Teacher of the Visually Impaired • The lyrics and sound file can be found on the Paths to Literacy website • http://www.pathstoliteracy.org/resources/farewell-song-9-ebae- contractions Unified English Braille A Place to Start April 2016 Donna Mayberry, M.Ed., NCUEB LAUREL REGIONAL PROGRAM, Lynchburg, VA [email protected] Webinar Content: • Overview of UEB • Unified English Braille Reference Sheets • Unified English Braille Student Progress Checklists • Converting Bookshare files into UEB • Teacher Relicensure: Option 8 • NCUEB • Questions Overview of UEB The Rules of Unified English Braille Second Edition 2013 Available as a PDF or BRF http://www.iceb.org/ueb.html Your new best Friend!!! What are teacher’s using to learn UEB? •Hadley School for the Blind •VDBVI Saturday Seminars •Update to UEB Self Directed Course- Available in Word, PDF, BRF, DXB http://www.cnib.ca/en/living/braille/Pages/Transcribers-UEB-Course.aspx •The new textbook that is being used in the VI Consortium is: Ashcroft's Programmed Instruction: Unified English Braille by M. Cay Holbrook 2014 Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille Contractions o'c o'clock (shortform) 4 dd (groupsign between letters) 6 to (wordsign unspaced from following word) 96 into (wordsign unspaced from following word) 0 by (wordsign unspaced from following word) # ble (groupsign following other letters) - com (groupsign at beginning of word) ,n ation (groupsign following other letters) ,y ally (groupsign following other letters) Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 2 Punctuation 7 opening and closing parentheses (round brackets) 7' closing square bracket 0' closing single quotation mark (inverted commas) ''' ellipsis -- dash (short dash) ---- double dash (long dash) ,7 opening square bracket Braille Not Used in Unified English Braille- 3 Composition signs (indicators) 1 non-Latin (non-Roman) letter indicator @ accent sign (nonspecific) @ print symbol indicator . -

The World Under My Fingers (PDF)

THE WORLD UNDER MY FINGERS PERSONAL REFLECTIONS ON BRAILLE Second Edition Edited by Barbara Pierce and Barbara Cheadle ii Copyright © 2005 by the National Federation of the Blind First edition 1995, second edition 2005 ISBN 1-885218-31-1 All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Braille Won’t Bite........................................1 Keeping Within the Lines ..........................2 The Chance to Read ................................11 Success Through Reading: Heather’s Story ........................................16 Reflections of a Lifelong Reader ..............20 That the Sighted May See ........................34 Braille: What Is It?....................................41 Your Child’s Right to Read ......................46 Study Confirms That Early Braille Education Is Vital ....................................53 Literacy Begins At Home..........................60 My Shameful Secret..................................65 iv Print or Braille? I Use Both!......................74 Can Braille Change the Future?................82 The Blessing of Braille..............................85 How to Increase Your Braille-Reading Speed ..............................90 Practice Makes Perfect ............................101 A Montana Yankee in Louis Braille’s Court ..............................107 What I Prefer: Courtesy Tips from a Blind Youth..........114 v INTRODUCTION All parents yearn for their children to be happy and healthy and to grow up to live sat- isfying and productive lives. If it were possi- ble to do so, we would arrange for them to be attractive, intelligent, ambitious, sensible, and funny—all the traits, in short, we wish we could boast and never have enough of, no matter how talented we are. Obviously our children do not grow up to exhibit all these traits, but most of them do well enough with the skills and attributes we do manage to impart to them. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription Mary Turner De Garmo Second Edition Revised and edited by Lawrence R. Smith Music Braille Transcriber Bettye Krolick Music Braille Consultant Beverly McKenney Music Braille Transcriber Sandra Kelly Music Braille Advisor Volume I National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped The Library of Congress Washington, DC 2005 Contents VOLUME I Foreword to the 1974 Edition . xi Preface to the 2005 Edition . xii Acknowledgments . xiii How to Use This Book . xiv Related Resources . xiv Overall Plan . xiv References to MBC-97 . xiv Using Computer Assistance . xv Taking the Course . xv References . xvi PART ONE: Basic Procedures and Transcribing Single-Staff Music 1 Formation of the Braille Note . 1 2 Eighth Notes, the Eighth Rest, and Other Basic Signs . 3 General Procedures . 4 Examples for Practice . 4 Procedures Specific to This Book . 7 Drills for Chapter 2 . 7 Exercises for Chapter 2 . 9 3 Quarter Notes, the Quarter Rest, and the Dot . 11 Examples for Practice . 11 Proofreading . 13 Drills for Chapter 3 . 13 Exercises for Chapter 3 . 15 4 Half Notes, the Half Rest, and the Tie . 17 Drills for Chapter 4 . 19 Exercises for Chapter 4 . 20 5 Whole and Double Whole Notes and Rests, Measure Rests, and Transcriber-Added Signs . 23 Various Print Methods for Showing Consecutive Measure Rests . 26 Reading Drill . 28 Drills for Chapter 5 . 30 Exercises for Chapter 5 . 31 6 Accidentals . 33 Directions for Brailling Accidentals . 33 Examples for Practice . 34 Drills for Chapter 6 . 35 i Exercises for Chapter 6 . 37 7 Octave Marks . 39 The Seven Octave Marks . -

Proceedings of the World Assembly of the World Council for the Welfare Of

PROCEEDINGS of the WORLD ASSEMBLY of the World Council for the Welfare of the Blind 31st July to 11th August, 1964 AmericanFoundation FOR'niEBUNDiNC. 15 WEST letfi r- NEW YORK, N.Y., 10011 cs^ PROCEEDINGS of the WORLD ASSEMBLY of the World Council for the Welfare of the Blind held at STATLER HILTON HOTEL. NEW YORK CITY. U.S.A. 31st JULY to nth August, 1964 The purposes of the Council shall be to work for the welfare of the blind and the prevention of blindness throughout the world by providing the means of consultation between organizations of and for the blind in different countries, and by the creation ot co-ordinating bodies where necessary, and for joint action wherever possible to- wards the introduction of minimum standards for the welfare of the blind in all parts ot the world and the improvement of such standards. World Council for the Welfare of the Blind Organisation Mondiale pour la Protection Sogiale des aveugles Registered Office Office of the Secretary-General 14, RUE Daru 224 Great Portland Street Paris (8), France London, W.I., England Certain of the papers included in these Proceedings were originally delivered in languages other than English and, while every care has been taken to ensure accuracy in translation, it is possible that some variations from the original structure and sense may have occurred. Furthermore, certain papers prepared in the English language were delivered by speakers not entirely familiar with that language. Some editing has there- fore been required. Our apologies are submitted for any inaccuracies that may have resulted therefrom. -

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 40

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 40 23 January 2018 DOI: 10.4400/akjh All ONIX standards and documentation – including this document – are copyright materials, made available free of charge for general use. A full license agreement (DOI: 10.4400/nwgj) that governs their use is available on the EDItEUR website. All ONIX users should note that this is the fourth issue of the ONIX codelists that does not include support for codelists used only with ONIX version 2.1. Of course, ONIX 2.1 remains fully usable, using Issue 36 of the codelists or earlier. Issue 36 continues to be available via the archive section of the EDItEUR website (http://www.editeur.org/15/Archived-Previous-Releases). These codelists are also available within a multilingual online browser at https://ns.editeur.org/onix. Codelists are revised quarterly. Go to latest Issue Layout of codelists This document contains ONIX for Books codelists Issue 40, intended primarily for use with ONIX 3.0. The codelists are arranged in a single table for reference and printing. They may also be used as controlled vocabularies, independent of ONIX. This document does not differentiate explicitly between codelists for ONIX 3.0 and those that are used with earlier releases, but lists used only with earlier releases have been removed. For details of which code list to use with which data element in each version of ONIX, please consult the main Specification for the appropriate release. Occasionally, a handful of codes within a particular list are defined as either deprecated, or not valid for use in a particular version of ONIX or with a particular data element. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

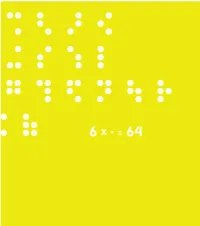

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Canadian National Institute for the Blind Fonds Terms of Use : Credit: Library and 1 Reproduction : Archives Canada, Acc

Canadian Natioanl Institute for the Blind fonds MG28-I233 Finding ai no MSS1114 vols. 1--211; 3866; 4978--4980; 4995; M-3795 R3647 Instrument de recherche no MSS1114 Mikan Hier. Access Place of File/Item BF date no Lvl. Media Title Label Container Copy code Scope and content Extent creation Language Dossier/ Date de Note Ecopy Dates No Niv. Support Titre Étiquette Conteneur Copie Code Portée et contenu Étendues Lieu de Langue Pièce rappel Mikan Hier. d'accès création Canadian National Institute for the Blind fonds Terms of use : Credit: Library and 1 reproduction : Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1996-81-1 / C- 3008759 Item Art 60 Years of Service, 1918-1978 R3647 211 1 C-097221 Open Canadian Institute For the Blind - Poster offset lithograph ; 097221 Unknown English 1978 59.1 x 64.6. Copyright : Canadian Institute for the Blind Terms of use : Credit: Library and 1 reproduction : Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1996-81-2 / C- Canadian National Institute For The Blind - 3008760 Item Art I.N.C.A. "Bon Anniversaire", 1918-1978 R3647 211 2 C-097220 Open offset lithograph ; 097220 Unknown French 1978 Poster 59.1 x 64.6. Copyright : Canadian National Instittute for the Blind. Terms of use : Credit: Library and 1 reproduction : Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1996-81-3 / C- 3008761 Item Art 1918-1978 "Happy 60th Birthday" - CNIB R3647 211 3 C-097219 Open CNIB - Poster. offset lithograph ; 097219 Unknown English 1978 59.1 x 64.6. Copyright : Canadian National Institute for the Blind. Terms of use : Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1977-37-1M / C-091888.