Issue 1 - - September 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CRIMSON HORROR.Fdr

(Name of Project) by (Name of First Writer) (Based on, If Any) Revisions by (Names of Subsequent Writers, in Order of Work Performed) Current Revisions by (Current Writer, date) Name (of company, if applicable) Address Phone Number 1 INT. MRS GILLYFLOWER’S HOUSE. PARLOUR. DUSK. 1 The crashing chords of a pipe organ. Someone is bashing out the tune of a grim and worthy hymn. We’re in a large, red- walled room, suffocating in Victorian bric-a-brac. Track past a series of strange still-lifes. Those oddly disturbing Victorian tableaux - colourful birds stuffed and arranged on twigs, surrounded by artificial flowers and under big glass bell-jars. Gas-light glints in the creatures’ beady glass eyes. The playing stops and a woman rises from the organ. We don’t see her face as she runs her hand over the line of bell-jars. MRS GILLYFLOWER Like pretty maids all in a row. She makes a gentle cooing. Then there’s another sound. A strangely horrible gurgling. Like a contented baby. A door opens behind the woman, framing a black-bonneted silhouette. CUT TO: 2 INT. MILL. SPIRAL STAIRCASE. DUSK. 2 Tap, tap, tap. A white cane clatters away as a pair of neat little feet ascend a darkened, spiral staircase. The staircase finally ends in a door, padded with old, stained green baize. Fumbling, lace-gloved female hands flutter around the bottom of the door, eventually locating a sort of cat-flap. The hands push through a bowl of grisly-looking food. From the other side of the door comes the sound of heavy, ragged breathing. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2021

Jan 21 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) did not gather in New York to celebrate the Great Detective’s 167th birthday this year, but the somewhat shorter long weekend offered plenty of events, thanks to Zoom and other modern technol- ogy. Detailed reports will be available soon at the web-site of The Baker Street Irregulars <www.bakerstreetirregulars.com>, but here are few brief paragraphs to tide you over: The BSI’s Distinguished Speaker on Thursday was Andrew Lycett, the author of two fine books about Conan Doyle; his topic was “Conan Doyle’s Questing World” (and close to 400 people were able to attend the virtual lecture); the event also included the announcement by Steve Rothman, editor of the Baker Street Journal, of the winner of the Morley-Montgomery Award for the best article the BSJ last year: Jessica Schilling (for her “Just His Type: An Analysis of the Découpé Warning in The Hound of the Baskervilles”). Irregulars and guests gathered on Friday for the BSI’s annual dinner, with Andrew Joffe offering the traditional first toast to Nina Singleton as The Woman, and the program continued with the usual toasts, rituals, and pap- ers; this year the toast to Mrs. Hudson was delivered by the lady herself, splendidly impersonated by Denny Dobry from his recreation of the sitting- room at 221B Baker Street. Mike Kean (the “Wiggins” of the BSI) presented the Birthday Honours (Irregular Shillings and Investitures) to Dan Andri- acco (St. Saviour’s Near King’s Cross), Deborah Clark (Mrs. Cecil Forres- ter), Carla Coupe (London Bridge), Ann Margaret Lewis (The Polyphonic Mo- tets of Lassus), Steve Mason (The Fortescue Scholarship), Ashley Polasek (Singlestick), Svend Ranild (A “Copenhagen” Label), Ray Riethmeier (Mor- rison, Morrison, and Dodd), Alan Rettig (The Red Lamp), and Tracy Revels (A Black Sequin-Covered Dinner-Dress). -

Orthia & Morgain 2016 the Gendered Culture of Scientific Competence

CULTURE OF SCIENTIFIC COMPETENCE 1 The Gendered Culture of Scientific Competence: A Study of Scientist Characters in Doctor Who 1963-2013 Lindy A. Orthia and Rachel Morgain The Australian National University Author Note Lindy A. Orthia, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science, The Australian National University; Rachel Morgain, School of Culture, History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University. Thanks to Emlyn Williams for statistical advice, and two anonymous peer reviewers for their useful suggestions. Address correspondence concerning this manuscript to Lindy A. Orthia, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science, The Australian National University, Peter Baume Building 42A, Acton ACT 2601, Australia. Email: [email protected] Published in Sex Roles. Final publication available at Springer via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0597-y CULTURE OF SCIENTIFIC COMPETENCE 2 Abstract The present study examines the relationship between gender and scientific competence in fictional representations of scientists in the British science fiction television program Doctor Who. Previous studies of fictional scientists have argued that women are often depicted as less scientifically capable than men, but these have largely taken a simple demographic approach or focused exclusively on female scientist characters. By examining both male and female scientists (n = 222) depicted over the first 50 years of Doctor Who, our study shows that, although male scientists significantly outnumbered female scientists in all but the most recent decade, both genders have consistently been depicted as equally competent in scientific matters. However, an in-depth analysis of several characters depicted as extremely scientifically non-credible found that their behavior, appearance, and relations were universally marked by more subtle violations of gender expectations. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

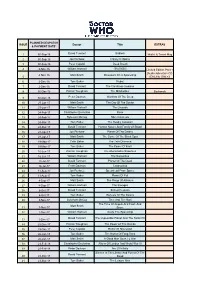

Issue Planned Despatch & Payment Date

PLANNED DESPATCH ISSUE Doctor Title EXTRAS & PAYMENT DATE* 1 30-Sep-16 David Tennant Gridlock Wallet & Travel Mug 2 30-Sep-16 Jon Pertwee Colony In Space 3 30-Sep-16 Peter Capaldi Deep Breath 4 4-Nov-16 William Hartnell 100,000BC Limited Edition Print + [Audio Adventure CD 4-Nov-16 Matt Smith Dinosaurs On A Spaceship 5 (ONLINE ONLY)] 6 2-Dec-16 Tom Baker Robot 7 2-Dec-16 David Tennant The Christmas Invasion 8 30-Dec-16 Patrick Troughton The Mindrobber Bookends 9 30-Dec-16 Peter Davison Warriors Of The Deep 10 27-Jan-17 Matt Smith The Day Of The Doctor 11 27-Jan-17 William Hartnell The Crusade 12 24-Feb-17 Christopher Eccleston Rose 13 24-Feb-17 Sylvester McCoy Silver Nemesis 14 24-Mar-17 Tom Baker The Deadly Assassin 15 24-Mar-17 David Tennant Human Nature And Family Of Blood 16 21-Apr-17 Jon Pertwee Planet Of The Daleks 17 21-Apr-17 Matt Smith The Curse Of The Black Spot 18 19-May-17 Colin Baker The Twin Dilemma 19 19-May-17 Tom Baker The Power Of Kroll 20 16-Jun-17 Patrick Troughton The Abominable Snowmen 21 16-Jun-17 William Hartnell The Sensorites 22 14-Jul-17 David Tennant Planet Of The Dead 23 14-Jul-17 Peter Davison Castrovalva 24 11-Aug-17 Jon Pertwee Spearhead From Space 25 11-Aug-17 Tom Baker Planet Of Evil 26 8-Sep-17 Matt Smith The Rings Of Akhaten 27 8-Sep-17 William Hartnell The Savages 28 6-Oct-17 David Tennant School Reunion 29 6-Oct-17 Tom Baker Genesis Of The Daleks 30 3-Nov-17 Sylvester McCoy Time And The Rani The Time Of Angels And Flesh And Matt Smith 31 3-Nov-17 Stone 32 1-Dec-17 William Hartnell Inside The Spaceship -

Lettering to the Max the Art & History of Calligraphy

KORERO PRESS Lettering to the Max Ivan Castro, Alex Trochut Summary Lettering, the drawing, designing, and illustration of words, has a personal uniqueness that is increasingly valued in today's digital society, whether personal or professional. This manual, by the internationally renowned Iván Castro, outlines the basic materials and skills to get you started. Typographical concepts and the principles of construction and composition are decoded. In addition, Ivan outlines several practical projects that allow the reader, not just to practice, but to develop their own ideas. In-depth but accessible, this book is the ideal beginner's guide and an excellent reference for the more well versed. Korero Press 9781912740079 Pub Date: 3/1/21 Contributor Bio On Sale Date: 3/1/21 Ivan Castro is a graphic designer based in Barcelona, Spain, who specializes in calligraphy, lettering, and $32.95 USD typography. His work involves everything from advertising to editorial, and from packaging to logo design and Discount Code: LON gig posters. Although Ivan claims to have no specific style, one could say that he has a strong respect for the Trade Paperback history of popular culture. He has been working in the field for 20 years, and has been teaching calligraphy 128 Pages and lettering for 15 years in the main design schools in Barcelona. He travels frequently, holding workshops Full color throughout Carton Qty: 24 and giving lectures at design festivals and conferences. Alex Trochut was born in 1981 in Barcelona, Spain. Art / Techniques After completing his studies at Elisava Escola Superior de Disseny, Alex established his own design studio in ART003000 Barcelona before relocating to New York City. -

NVS 11-1-7 L-Lawrence.Pdf

Doctor Who and the Neo-Victorian Christmas Serial Tradition Lindsy Lawrence (University of Arkansas – Fort Smith, Arkansas, USA) Abstract: Christmas stories are a tradition in British serial literature, be it the annuals and special weekly and monthly magazines published in the nineteenth century or the Christmas- themed episodes of popular television serials today. Festival literature produces an ‘eerie’ sense of past, present, and future, and many of these productions evoke past traumas for narrative impact. For example, Christmas editions of Charles Dickens’s Household Words and All the Year Round provided readers with specially commissioned stories that explored past traumas in order to enable their characters to morally improve, to the betterment of themselves and society. The rebooted Doctor Who, in ‘The Next Doctor’ (2008), ‘A Christmas Carol’ (25 December 2010), and ‘The Snowmen’ (2012), has reinvented the Victorian Christmas serial both via narrative echoes and explicit use of neo-Victorian and steampunk visual designs. In so doing, these neo-Victorian TV specials critique some of the same social problems as Dickens did, commenting on greed and the concept of ‘Victorian values’ while also remediating the affective nature of Christmas stories to help people come to terms with past traumas. Keywords: All the Year Round, Christmas serials, Christmas specials, Russell T. Davies, Charles Dickens, Doctor Who, Household Words, Steven Moffat, Sherlock. ***** In the first new Doctor Who Christmas special, Rose Tyler (Billie Piper) explains to her much put-upon boyfriend, Mickey Smith (Noel Clarke), “You just forget about Christmas and things in the TARDIS. They don’t exist. You get sort of timeless” (Hawes and Davies 2005: 6:14-6:18). -

6Th Doctor Novelisation Eric Saward Pub Date

BBC PHYSICAL AUDIO Doctor Who: Revelation of the Daleks : 6th Summary: Doctor Novelisation The Doctor and Peri land on the planet Necros to visit the Eric Saward funerary home Tranquil Repose—where the dead are Pub Date: 7/1/20 interred and the near-dead placed in suspended animation $36.95 USD until such time as their conditions can be cured. But the 1 pages Great Healer of Tranquil Repose is far from benign. Under his command, Daleks guard the catacombs where sickening experiments are conducted on human bodies. The new life he offers the dying comes at a terrible cost—and the Doctor and Peri are being lured into a trap that will change them forever. Roarings from Further Out : Four Weird Summary: Novellas by Algernon Blackwood From one of the greatest and most prolific authors of 20th Algernon Blackwood, Xavier Aldana Reyes century weird fiction come four of the very best strange Pub Date: 7/1/20 stories ever told. In "The Willows," two men become $15.95 USD stranded on an island in the Danube delta, only to find that 288 pages they might be in the domain of some greater power from beyond the limits of human experience. "The Wendigo" features a hunting party in Ontario who begin to fear that they are being stalked by an entity thought to be confined to legend. In "The Man Whom the Trees Loved," a couple is driven apart as the husband is enthralled by the possessive and jealous spirits dwelling in the nearby forest. And lastly, in conversation with the occult detective and physician Dr. -

The Wall of Lies

The Wall of Lies Number 149 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA Final STATE Adelaide, July--August 2014 WEATHER: Venus, pre-1957 Free Who’s not coming to Adelaide? by staff writers Time Lords have been messing with the dematerialisation circuit. On 11 June 2013 the BBC announced a worldwide tour of the current Doctor Who regulars Peter Capaldi and Jenna Coleman. Doctor Who: The World Tour will visit such far off locales as New York, Mexico City, Seoul, Sydney and Rio de Janeiro. High on the list of places they are not visiting is Adelaide. Steven Moffat, show runner who is accompanying part of the tour, is understood to have been a strong advocate for Metebelis III and Gallifrey. However compromises have been made, and visits O u N t to London and Cardiff are also planned. Doctor Who No ow Moffat; trapped in a rectangle, fans in the UK and also Great Britain are understood ! but quite well dressed. to be overjoyed at this unprecedented contact with the stars. ABC: It’s 24 August for Doctor Who! by staff writers ABC plays new Who as soon as possible. ABC announced the fast track of Doctor Who series eight on 29 June, only two days after the BBC confirmed the premiere date 50th Programme of 23 August on BBC One. This will follow the 2013 repeats in the schedule and be only fourteen hours after the UK premiere. O u ABC Managing Director Mark Scott told The Wall of Lies, ”I think S t So on we welcome a continuous series not a split one. -

Doctor Who Companion’S Toolkit

FANDOM FORWARD DOCTOR WHO COMPANION’S TOOLKIT 1 Fandom Forward is a project of the Harry Potter Alliance. Founded in 2005, the Harry Potter Alliance is an international non-profit that turns fans into heroes by making activism accessible through the power of story. This toolkit provides resources for fans of Doctor Who to think more deeply about the social issues represented in the story and take action in our own world. Contact us: [email protected] #FandomForward @TheHPAlliance 2 CONTENTS Introduction Facilitator Tips Representation Issue 1: Feminism Talk it Out Take Action Issue 2: Indigenous Rights Talk it Out Take Action Issue 3: War Talk it Out Take Action Resources Thanks 3 INTRODUCTION “Somewhere there’s danger, somewhere there’s injustice, somewhere else, the tea’s getting cold.” The universe is a wonderful, terrifying, ever-expanding adventure. There’s injustice to overcome, people to save, communities to empower, and a lot to learn. Through the Doctor and their companions’ journeys, we learn that no matter the cost it’s important to try our very best to help people because every life is important. And, thanks to the Doctor, we know we can’t help everyone by ourselves. We have to rely on our friends, our communities, and the help of strangers to make the biggest impact. While no journey is ever easy, we hope you’ll take this one with us. In this Companion’s Toolkit, we’ll be talking about feminism, indigenous rights, and the history and effects of war. These topics can be difficult, and solutions to the problems we’re addressing aren’t always clear, but that doesn’t mean we can’t try. -

Released with Audio Only Anim

Updated – 7/26/15 Released Lost – Won’t be released unless found Unreleased A – Released with Audio only Anim – Released with Lost video replaced by Animation CD – Audio only released on CD (Doctor Who: The Lost TV Episodes: Collections) Release Scheduled The First Doctor – William Hartnell Season 1 001 – An Unearthly Child (1–4) 002 – The Daleks (1–7) 003 – The Edge of Destruction (1–2) 004 – Marco Polo (1–7) CD 005 – The Keys of Marinus (1–6) 006 – The Aztecs (1–4) 007 – The Sensorites (1–6) 008 – The Reign of Terror (1–3,4–5Anim,6) CD Season 2 009 – Planet of Giants (1–3) 010 – The Dalek Invasion of Earth (1–6) 011 – The Rescue (1–2) 012 – The Romans (1–4) 013 – The Web Planet (1–6) 014 – The Crusade (1,2A,3,4A) CD 015 – The Space Museum (1–4) 016 – The Chase (1–6) 017 – The Time Meddler (1–4) Season 3 018 – Galaxy 4 (1–2,3,4) CD 019 – Mission to the Unknown (1) 020 – The Myth Makers (1–4) CD 021 – The Daleks' Master Plan (1,2,3–4,5,6–9,10,11–12) CD 022 – The Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Eve (1–4) CD 023 – The Ark (1–4) 024 – The Celestial Toymaker (1–3,4) CD 025 – The Gunfighters (1–4) 026 – The Savages (1–4) CD 027 – The War Machines (1–4) Season 4 028 – The Smugglers (1–4) CD 029 – The Tenth Planet (1–3,4) CD The Second Doctor – Patrick Troughton 030 – The Power of the Daleks (1–6) CD 031 – The Highlanders (1–4) CD 032 – The Underwater Menace (1,2,3,4) CD 033 – The Moonbase (1A,2,3A,4) CD 034 – The Macra Terror (1–4) CD 035 – The Faceless Ones (1,2,3,4–6) CD 036 – The Evil of the Daleks (1,2,3–7) CD Season 5 037 – The Tomb of the -

“Strong Female Characters” an Analytical Look at Representation in Moffat-Era Doctor

Q&A How did you become involved in doing research? I took Milton Wendland’s “Studies in: Queer Film and TV” class the summer of 2012. During this class I learned that I could write on my favourite show through an academic and feminist lens. I was shown that academic work on film and television was a necessity in an ever-expanding media-based society. Milton taught me that we must be critical when watching shows because of the massive influence the media has on society and culture. I also learned that if I don’t use my position of privilege as a student at a top research university to at least try to make a difference, I can’t assume anything will change. Nichole Flynn How is the research process different from what you expected? It’s a lot harder to find academic sources on my topic. Much of what I’m HOMETowN researching is in its infancy in terms of being studied at the academic level. Hutchinson, Kansas There is also a huge disconnect between what is considered scholastic work and what is “merely fandom” in terms of analyzing Doctor Who. Given my focus on MAJOR representation of women and minorities, it can be difficult to find published Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies sources that were not written by cisgender, heterosexual, white men, which has shown me the gap in research that I aim to help fill. ACADEMIC LEVEL Senior What is your favorite part of doing research? I love being able to write on my favourite show.