Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuning Into the On-Demand Streaming Culture—Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’S Media Landscape

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Tuning Into the On-Demand Streaming Culture—Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’s Media Landscape Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2152q2t4 Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 27(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Roth, Blaine Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/LR8271048856 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TUNING INTO THE ON-DEMAND STREAMING CULTURE— Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’s Media Landscape Blaine Roth Abstract Hollywood television and film production has largely been unionized since the early 1930s. Today, due in part to technological advances, the industry is much more expansive than it has ever been, yet the Hollywood unions, known as “guilds,” have arguably not evolved at a similar pace. Although the guilds have adapted to the needs of their members in many aspects, have they suc- cessfully adapted to the evolving Hollywood business model? This Comment puts a focus on the Writers Guild of America, Directors Guild of America, and the Screen Actors Guild, known as SAG-AFTRA following its merger in 2012, and asks whether their respective collective bargaining agreements are out-of- step with the evolution of the industry over the past ten years, particularly in the areas of new media and the direct-to-consumer model. While analyzing the guilds in the context of the industry environment as it is today, this Com- ment contends that as the guilds continue to feel more pronounced effects from the evolving media landscape, they will need to adapt at a much more rapid pace than ever before in order to meet the needs of their members. -

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

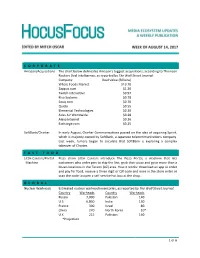

1 of 6 C O R P O R a T E Amazon/Acquisitions the Chart

CORPORATE Amazon/Acquisitions The chart below delineates Amazon’s biggest acquisitions, according to Thomson Reuters Deal Intelligence, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Company Deal Value (Billions) Whole Foods MarKet $13.70 Zappos.com $1.20 Twitch Interactive $0.97 Kiva Systems $0.78 Souq.com $0.70 Quidsi $0.55 Elemental Technologies $0.30 Atlas Air Worldwide $0.28 Alexa Internet $0.26 Exchange.com $0.25 SoftBanK/Charter In early August, Charter Communications passed on the idea of acquiring Sprint, which is majority owned by SoftBanK, a Japanese telecommunications company. Last week, rumors began to circulate that SoftBank is exploring a complex taKeover of Charter. FAST FOOD Little Caesars/Portal Pizza chain Little Caesars introduce The Pizza Portal, a machine that lets Machine customers who order pies to skip the line, grab their pizza and go in more than a dozen locations in the Tucson (AZ) area. How it worKs: download an app to order and pay for food, receive a three digit or QR code and once in the store enter or scan the code to open a self-service hot box at the shop. GLOBAL Nuclear Warheads Estimated nuclear warhead inventories, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Country Warheads Country Warheads Russia 7,000 Pakistan 140 U.S. 6,800 India 130 France 300 Israel 80 China 270 North Korea 10* U.K. 215 Pakistan 140 *Projection 1 of 6 MOVIES TicKet Sales According to Nielsen, North American box office ticKet sales are down 2.9% even with ticKet prices higher than the prior year – maKing up for some of the diminished theater attendance. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media contacts: June 4, 2012 Heather Wilner Verizon 908-559-6407 [email protected] Cathy Clarke CNC Associates for Olympusat 508-833-8533 [email protected] Verizon FiOS TV Becomes the Nation’s Leading Provider of Spanish-Language Programming FiOS TV Gives Customers The Most HD Spanish-language Channels Available Nationwide, With 10 New Channels from Olympusat and Multimedios Television NEW YORK – Verizon FiOS TV has become the country’s leading television provider of Spanish-language channels, announcing today the launch of 10 new Spanish-language channels in high definition. Verizon now offers up to 75 Spanish-language channels on FiOS TV, dependent on the local channels available in each market. Nine of the 10 new Spanish-language HD channels are provided by Olympusat Inc., a leading independent distributor of Hispanic content in the United States. Known as ULTRA Verizon News Release, page 2 HDPlex, the Olympusat channels are: Ultra Cine, Ultra Fiesta, Ultra Kidz, Ultra Mex, Ultra Luna, Ultra Macho, Ultra Film, Ultra Docu and Ultra Clásico. The 10th channel, Multimedios Television, offers Spanish-language family and entertainment programming broadcast from Monterrey, Mexico. FiOS TV recently completed the launch of all 10 channels. In addition, Verizon announced last week a new multi-year carriage agreement with Univision Communications, Inc., which includes the launch of three new networks – Univision Deportes, Univision tlnovelas and FOROtv – as well as rights for multiplatform and on demand viewing. “Our customers have told us that high-quality Spanish-language programming helps to keep their culture alive, and we’re helping to make that happen by giving them the content that they want,” said Michelle Webb, director of content strategy and acquisition for Verizon. -

TRANSCRIPT CMCSA - Comcast Corp at UBS Global Media and Communications Conference

Client Id: 77 THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT CMCSA - Comcast Corp at UBS Global Media and Communications Conference EVENT DATE/TIME: DECEMBER 04, 2017 / 1:45PM GMT THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS | www.streetevents.com | Contact Us ©2017 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Thomson Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Thomson Reuters. 'Thomson Reuters' and the Thomson Reuters logo are registered trademarks of Thomson Reuters and its affiliated companies. Client Id: 77 DECEMBER 04, 2017 / 1:45PM, CMCSA - Comcast Corp at UBS Global Media and Communications Conference CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Michael J. Cavanagh Comcast Corporation - CFO and Senior EVP CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS John Christopher Hodulik UBS Investment Bank, Research Division - MD, Sector Head of the United States Communications Group, and Telco and Pay TV Analyst PRESENTATION John Christopher Hodulik - UBS Investment Bank, Research Division - MD, Sector Head of the United States Communications Group, and Telco and Pay TV Analyst Okay. If everyone can please take their seats. Again, I'm John Hodulik, the media, telecom and cable infrastructure analyst here at UBS. And welcome to the 45th Annual Media and Telecom Conference. I'm pleased to announce our keynote speaker this morning is Mike Cavanagh, CFO of Comcast. Mike, thanks for being here. Michael J. Cavanagh - Comcast Corporation - CFO and Senior EVP Thanks for having us. Great to be here once again. Three years in a row. John Christopher Hodulik - UBS Investment Bank, Research Division - MD, Sector Head of the United States Communications Group, and Telco and Pay TV Analyst That's right. -

Private Equity

Private Equity Our Private Equity lawyers work with the financial sponsor and fund community to structure, negotiate, and consummate acquisitions and financings of private and public companies, exit transactions, going-private transactions, stock-for-stock acquisitions, spinoff transactions, and acquisitions of minority interests. In addition, we advise management teams and sponsors in connection with rollover investments and management incentive plans. Drawing on the full resources of our Investment Management Group, our private equity lawyers also handle fund structuring and formation. We work regularly with large, middle-market, and growth equity financial sponsors and their portfolio companies across a wide range of industries, including asset management and financial services, business services, consumer and retail, energy services, food and restaurant, life sciences and pharmaceutical, manufacturing, professional and other services, publishing and media, software and technology, and telecommunications. Our clients collaborate directly with our partners, who are passionate about their work and their clients' goals, and who have significant experience in a wide range of transactions, including large and complex deals. Our private equity lawyers anticipate potential issues and develop creative approaches to meet both buyer and seller goals. We become deeply rooted in our clients' investment strategies, earning their trust so that we can adeptly and efficiently negotiate on their behalf to reach commercially viable and reasonable outcomes. Our straightforward negotiating style with potential investment targets helps set the stage for a highly productive relationship. We often are asked to act as counsel for newly acquired portfolio companies and to assist them with a wide range of strategic and commercial needs across their investment life cycle. -

Article Title

International In-house Counsel Journal Vol. 11, No. 41, Autumn 2017, 1 The Future is Cordless: How the Cordless Future will Impact Traditional Television SABRINA JO LEWIS Director of Business Affairs, Paramount Television, USA Introduction A cord-cutter is a person who cancels a paid television subscription or landline phone connection for an alternative Internet-based or wireless service. Cord-cutting is the result of competitive new media platforms such as Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, iTunes and YouTube. As new media platforms continue to expand and dominate the industry, more consumers are prepared to cut cords to save money. Online television platforms offer consumers customized content with no annual contract for a fraction of the price. As a result, since 2012, nearly 8 million United States households have cut cords, according to Wall Street research firm MoffettNathanson.1 One out of seven Americans has cut the cord.2 Nielsen started counting internet-based cable-like service subscribers at the start of 2017 and their data shows that such services have at least 1.3 million customers and are still growing.3 The three most popular subscription video-on-demand (“SVOD”) providers are Netflix, Amazon Prime and HULU Plus. According to Entertainment Merchants Association’s annual industry report, 72% of households with broadband subscribe to an SVOD service.4 During a recent interview on CNBC, Corey Barrett, a senior media analyst at M Science, explained that Hulu, not Netflix, appears to be driving the recent increase in cord-cutting, meaning cord-cutting was most pronounced among Hulu subscribers.5 Some consumers may decide not to cut cords because of sports programming or the inability to watch live programing on new media platforms. -

ATTACHMENT a the FCC’S Newspaper-Broadcast Cross-Ownership Rule: an Analysis

ATTACHMENT A The FCC’s Newspaper-Broadcast Cross-Ownership Rule: An Analysis by Douglas Gomery Douglas Gomery is professor of media economics and history in the College of Journalism at the University of Maryland. His most recent book, Who Owns the Media? (with Ben Compaine), won the 2000 Picard Prize for the best media economics book of the year. He has published 10 other books, some 500 articles in scholarly journals and encyclopedias, written a column, “The Economics of Television,” for the American Journalism Review, and consulted for both the Federal Communications Commission and the Government Accounting Office. Acknowledgments. The author wishes to thank Eileen Appelbaum for her skills in fashioning this study, and Marilyn Moon for her help in crafting its arguments and for her inspiration as one of America's best public policy analysts. ECONOMIC POLICY INSTITUTE 1 Introduction In 1975 the Federal Communications Commission initiated the newspaper-broadcast cross- ownership rule, which bars a single company from owning a newspaper and a broadcast station in the same market. The purpose of the rule is to prevent any single corporate entity from becoming too powerful a single voice within a community, and thus the rule seeks to maximize diversity under the conditions dictated by the marketplace. The cross-ownership ban does not prevent a newspaper from owning a broadcast station in another market, and indeed many large newspapers — such as the New York Times and the Washington Post — own and operate broadcast stations outside their flagship cities (Compaine and Gomery 2000). Media organizations have largely opposed the rule since its inception, and their prospects for eliminating or limiting it brightened in 1996, when the new Telecommunications Act directed the FCC to continually review all ownership rules. -

Content Remains King, but Youtube Builds the Throne of the Future Content Creation May Have the Lowest of All Barriers to Entry

Sector Bulletin_ Digital Media and Internet Technology_ March 2014_ Content Remains King, but YouTube Builds the Throne of the Future Content creation may have the lowest of all barriers to entry. Anyone with access to a smartphone and wi-fi can create and distribute endless GBs of content. However, replicating this process at scale, demonstrating audience reach, authentication and measurement and then syndicating this content, that same list of creators contracts to a few. Fewer still are the options available to a producer to reach a mass audience in today’s increasingly fragmented, device agnostic world. Available platform alternatives include obtaining distribution with a major cable television or satellite operator, partnering with an over the top (OTT) provider such as Netflix, Hulu or Amazon, or joining one of thousands of multi-channel networks on YouTube . Distribution Alternatives National Cable Distribution Nirvana for any producer or content creator is signing a distribution agreement with a cable, telco or satellite provider. In October 2013, music mogul Sean Combs launched Revolt TV, filling the void of music television left by MTV. Revolt launched on both Comcast and Time Warner Cable to 25 million subscribers. It is rare for a new, non-repurposed cable channel to obtain national distribution. In addition to Combs’ celebrity (he produced a number of hit shows for MTV in the 2000s), the fledgling network looks to rely upon a strong online and social presence. The hope is the latter could help mitigate the cable TV boogieman of “cord cutting” or removal of cable service for other online or OTT alternatives. -

The Streaming Wars+: an Analysis of Anticompetitive Business Practices in Streaming Business

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title The Streaming Wars+: An Analysis of Anticompetitive Business Practices in Streaming Business Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8m05g3fd Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 28(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Pakula, Olivia Publication Date 2021 DOI 10.5070/LR828153859 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE STREAMING WARS+: An Analysis of Anticompetitive Business Practices in Streaming Business Olivia Pakula* Abstract The recent rise of streaming platforms currently benefits consumers with quality content offerings at free or at relatively low cost. However, as these companies’ market power expands through vertical integration, current anti- trust laws may be insufficient to protect consumers from potential longterm harms, such as increased prices, lower quality and variety of content, or erosion of data privacy. It is paramount to determining whether streaming services engage in anticompetitive business practices to protect both competition and consumers. Though streaming companies do not violate existing antitrust laws because consumers are not presently harmed, this Comment thus explores whether streaming companies are engaging in aggressive business practices with the potential to harm consumers. The oligopolistic streaming industry is combined with enormous barriers to entry, practices of predatory pricing, imperfect price discrimination, bundling, disfavoring of competitors on their platforms, huge talent buyouts, and nontransparent use of consumer data, which may be reason for concern. This Comment will examine the history of the entertainment industry and antitrust laws to discern where the current business practices of the streaming companies fit into the antitrust analysis. This Comment then considers potential solutions to antitrust concerns such as increasing enforcement, reforming the consumer welfare standard, public util- ity regulation, prophylactic bans on vertical integration, divestiture, and fines. -

La Maitrise Du Streaming, Un Nouvel Enjeu De Taille Pour Les Groupes Médias

La maitrise du streaming, un nouvel enjeu de taille pour les groupes médias Walt Disney Company a annoncé l’acquisition de 33% du capital de BAM Tech, société indépendante spécialisée dans les technologies de streaming vidéo, née au sein de MLB Advanced Media, une division de la Major League Baseball. Il s’agit de la dernière opération en date de rapprochement entre un acteur des contenus et un prestataire technologique devenu incontournable au moment où les services OTT de streaming en direct se multiplient. • BAM Tech passe du Baseball à l’univers Disney Walt Disney Company a annoncé l’acquisition de 33% du capital de BAM Tech, société indépendante spécialisée dans les technologies de streaming vidéo, née au sein de MLB Advanced Media, une division de la Major League Baseball créée en 2000 pour le lancement de MLB.TV qui diffuse en ligne les compétitions de la League. MLBAM reste la copropriété des 30 principales équipes de Baseball professionnel. L’opération valorise BAM Tech à hauteur de à 3,5 milliards de dollars. Et Disney disposerait également d’une option de 4 ans pour acquérir 33% supplémentaires. MLBAM a pris une autonomie croissante pour s’émanciper de l’univers du Baseball (applications MLB.TV) et plus globalement du sport U.S jusqu’à accorder son indépendance à BAM Tech, son entité opérationnelle en août 2015. Celle-ci est désormais devenue un prestataire de service majeur pour les grands networks et autres propriétaires de contenus. Ainsi, BAM Tech a réussi à se diversifier en gérant le streaming de HBO Now et PlayStation Vue après avoir fait ses preuves au sein de MLBAM dans le sport en direct via des plates- formes en marque blanche (WatchESPN, WWE Network, Yankee’s Yes Network, PGA Tour Live, les sites et applications de la NHL ou encore 120 sports et Ice Network, spécialiste des sports de glisse).