The Streaming Wars+: an Analysis of Anticompetitive Business Practices in Streaming Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

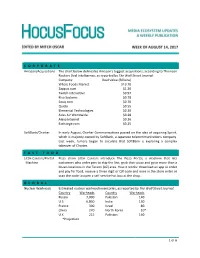

1 of 6 C O R P O R a T E Amazon/Acquisitions the Chart

CORPORATE Amazon/Acquisitions The chart below delineates Amazon’s biggest acquisitions, according to Thomson Reuters Deal Intelligence, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Company Deal Value (Billions) Whole Foods MarKet $13.70 Zappos.com $1.20 Twitch Interactive $0.97 Kiva Systems $0.78 Souq.com $0.70 Quidsi $0.55 Elemental Technologies $0.30 Atlas Air Worldwide $0.28 Alexa Internet $0.26 Exchange.com $0.25 SoftBanK/Charter In early August, Charter Communications passed on the idea of acquiring Sprint, which is majority owned by SoftBanK, a Japanese telecommunications company. Last week, rumors began to circulate that SoftBank is exploring a complex taKeover of Charter. FAST FOOD Little Caesars/Portal Pizza chain Little Caesars introduce The Pizza Portal, a machine that lets Machine customers who order pies to skip the line, grab their pizza and go in more than a dozen locations in the Tucson (AZ) area. How it worKs: download an app to order and pay for food, receive a three digit or QR code and once in the store enter or scan the code to open a self-service hot box at the shop. GLOBAL Nuclear Warheads Estimated nuclear warhead inventories, as reported by The Wall Street Journal: Country Warheads Country Warheads Russia 7,000 Pakistan 140 U.S. 6,800 India 130 France 300 Israel 80 China 270 North Korea 10* U.K. 215 Pakistan 140 *Projection 1 of 6 MOVIES TicKet Sales According to Nielsen, North American box office ticKet sales are down 2.9% even with ticKet prices higher than the prior year – maKing up for some of the diminished theater attendance. -

TRANSCRIPT CMCSA - Comcast Corp at UBS Global Media and Communications Conference

Client Id: 77 THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT CMCSA - Comcast Corp at UBS Global Media and Communications Conference EVENT DATE/TIME: DECEMBER 04, 2017 / 1:45PM GMT THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS | www.streetevents.com | Contact Us ©2017 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Thomson Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Thomson Reuters. 'Thomson Reuters' and the Thomson Reuters logo are registered trademarks of Thomson Reuters and its affiliated companies. Client Id: 77 DECEMBER 04, 2017 / 1:45PM, CMCSA - Comcast Corp at UBS Global Media and Communications Conference CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Michael J. Cavanagh Comcast Corporation - CFO and Senior EVP CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS John Christopher Hodulik UBS Investment Bank, Research Division - MD, Sector Head of the United States Communications Group, and Telco and Pay TV Analyst PRESENTATION John Christopher Hodulik - UBS Investment Bank, Research Division - MD, Sector Head of the United States Communications Group, and Telco and Pay TV Analyst Okay. If everyone can please take their seats. Again, I'm John Hodulik, the media, telecom and cable infrastructure analyst here at UBS. And welcome to the 45th Annual Media and Telecom Conference. I'm pleased to announce our keynote speaker this morning is Mike Cavanagh, CFO of Comcast. Mike, thanks for being here. Michael J. Cavanagh - Comcast Corporation - CFO and Senior EVP Thanks for having us. Great to be here once again. Three years in a row. John Christopher Hodulik - UBS Investment Bank, Research Division - MD, Sector Head of the United States Communications Group, and Telco and Pay TV Analyst That's right. -

Article Title

International In-house Counsel Journal Vol. 11, No. 41, Autumn 2017, 1 The Future is Cordless: How the Cordless Future will Impact Traditional Television SABRINA JO LEWIS Director of Business Affairs, Paramount Television, USA Introduction A cord-cutter is a person who cancels a paid television subscription or landline phone connection for an alternative Internet-based or wireless service. Cord-cutting is the result of competitive new media platforms such as Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, iTunes and YouTube. As new media platforms continue to expand and dominate the industry, more consumers are prepared to cut cords to save money. Online television platforms offer consumers customized content with no annual contract for a fraction of the price. As a result, since 2012, nearly 8 million United States households have cut cords, according to Wall Street research firm MoffettNathanson.1 One out of seven Americans has cut the cord.2 Nielsen started counting internet-based cable-like service subscribers at the start of 2017 and their data shows that such services have at least 1.3 million customers and are still growing.3 The three most popular subscription video-on-demand (“SVOD”) providers are Netflix, Amazon Prime and HULU Plus. According to Entertainment Merchants Association’s annual industry report, 72% of households with broadband subscribe to an SVOD service.4 During a recent interview on CNBC, Corey Barrett, a senior media analyst at M Science, explained that Hulu, not Netflix, appears to be driving the recent increase in cord-cutting, meaning cord-cutting was most pronounced among Hulu subscribers.5 Some consumers may decide not to cut cords because of sports programming or the inability to watch live programing on new media platforms. -

La Maitrise Du Streaming, Un Nouvel Enjeu De Taille Pour Les Groupes Médias

La maitrise du streaming, un nouvel enjeu de taille pour les groupes médias Walt Disney Company a annoncé l’acquisition de 33% du capital de BAM Tech, société indépendante spécialisée dans les technologies de streaming vidéo, née au sein de MLB Advanced Media, une division de la Major League Baseball. Il s’agit de la dernière opération en date de rapprochement entre un acteur des contenus et un prestataire technologique devenu incontournable au moment où les services OTT de streaming en direct se multiplient. • BAM Tech passe du Baseball à l’univers Disney Walt Disney Company a annoncé l’acquisition de 33% du capital de BAM Tech, société indépendante spécialisée dans les technologies de streaming vidéo, née au sein de MLB Advanced Media, une division de la Major League Baseball créée en 2000 pour le lancement de MLB.TV qui diffuse en ligne les compétitions de la League. MLBAM reste la copropriété des 30 principales équipes de Baseball professionnel. L’opération valorise BAM Tech à hauteur de à 3,5 milliards de dollars. Et Disney disposerait également d’une option de 4 ans pour acquérir 33% supplémentaires. MLBAM a pris une autonomie croissante pour s’émanciper de l’univers du Baseball (applications MLB.TV) et plus globalement du sport U.S jusqu’à accorder son indépendance à BAM Tech, son entité opérationnelle en août 2015. Celle-ci est désormais devenue un prestataire de service majeur pour les grands networks et autres propriétaires de contenus. Ainsi, BAM Tech a réussi à se diversifier en gérant le streaming de HBO Now et PlayStation Vue après avoir fait ses preuves au sein de MLBAM dans le sport en direct via des plates- formes en marque blanche (WatchESPN, WWE Network, Yankee’s Yes Network, PGA Tour Live, les sites et applications de la NHL ou encore 120 sports et Ice Network, spécialiste des sports de glisse). -

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report Trends in 2016 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. Digital Original Series — Global Demand Report | Trends in 2016 Executive Summary } This year saw the release of several new, popular digital } The release of popular titles such as The Grand Tour originals. Three first-season titles — Stranger Things, and The Man in the High Castle caused demand Marvel’s Luke Cage, and Gilmore Girls: A Year in the for Amazon Video to grow by over six times in some Life — had the highest peak demand in 2016 in seven markets, such as the UK, Sweden, and Japan, in Q4 of out of the ten markets. All three ranked within the 2016, illustrating the importance of hit titles for SVOD top ten titles by peak demand in nine out of the ten platforms. markets. } Drama series had the most total demand over the } As a percentage of all demand for digital original series year in these markets, indicating both the number and this year, Netflix had the highest share in Brazil and popularity of titles in this genre. third-highest share in Mexico, suggesting that the other platforms have yet to appeal to Latin American } However, some markets had preferences for other markets. genres. Science fiction was especially popular in Brazil, while France, Mexico, and Sweden had strong } Non-Netflix platforms had the highest share in Japan, demand for comedy-dramas. where Hulu and Amazon Video (as well as Netflix) have been available since 2015. Digital Original Series with Highest Peak Demand in 2016 Orange Is Marvels Stranger Things Gilmore Girls Club De Cuervos The New Black Luke Cage United Kingdom France United States Germany Mexico Brazil Sweden Russia Australia Japan 2 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. -

TRANSCRIPT CMCSA - Comcast Corp at Bank of America Merrill Lynch Media, Communications and Entertainment Conference

THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT CMCSA - Comcast Corp at Bank of America Merrill Lynch Media, Communications and Entertainment Conference EVENT DATE/TIME: SEPTEMBER 14, 2016 / 3:00PM GMT THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS | www.streetevents.com | Contact Us ©2016 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Thomson Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Thomson Reuters. 'Thomson Reuters' and the Thomson Reuters logo are registered trademarks of Thomson Reuters and its affiliated companies. SEPTEMBER 14, 2016 / 3:00PM, CMCSA - Comcast Corp at Bank of America Merrill Lynch Media, Communications and Entertainment Conference CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Steve Burke Comcast Corporation - Senior EVP and CEO, NBCUniversal CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Jessica Reif Cohen Bank of America Merrill Lynch - Analyst PRESENTATION Jessica Reif Cohen - Bank of America Merrill Lynch - Analyst Good morning, hi. Thank you so much for coming. It's hard to believe you have been at Comcast for 18 years. Steve Burke - Comcast Corporation - Senior EVP and CEO, NBCUniversal That's true. Jessica Reif Cohen - Bank of America Merrill Lynch - Analyst It's really amazing. So let's focus on NBCU. It's flourished under your stewardship and Comcast's ownership. When you originally bought the asset, NBCU was obviously a turnaround story and to say the least the turnaround at NBCU has been outstanding. How does your strategy shift now that you are managing an asset that has been turned around and is now one of the leading media companies in the world? Steve Burke - Comcast Corporation - Senior EVP and CEO, NBCUniversal So let me start by talking a little bit about the Company that we bought and the Company as it is today. -

Clarendon School Leaders Preparing to Share Services

White House’s top lawyer is leaving THURSDAY, AUGUST 30, 2018 75 CENTS Trump praises McGahn, who has played key role in many issues SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 BY KEN THOMAS and ZEKE MILLER Wednesday. had nothing to do with his inter- McGahn’s exit continues the views with the special counsel in- 3 SECTIONS, 22 PAGES | VOL. 123, NO. 224 The Associated Press churn of top officials as the admin- vestigating possible Trump cam- WASHINGTON — White House istration sets records for turnover paign collusion with Russia in the IN TODAY’S EDITION Counsel Don McGahn, a conse- and the White House struggles to 2016 election. quential insider in President Don- fill key vacancies. Pressed by reporters, Trump ald Trump’s legal storms and suc- Unlike some less-amiable separa- said he had approved the attor- cesses and a key figure in the ad- tions, however, Trump praised Mc- ney’s interviews and was uncon- ministration’s handling of the Rus- Gahn as “a really good guy” who cerned about anything McGahn sia investigation, will be leaving in has done “an excellent job.” the fall, the president announced Trump said McGahn’s departure SEE McGAHN, PAGE A6 LABOR From 8 felonies to successful Sumter DAY 2018 BAIL BONDSMAN ‘I use what I know to help people along the way. All I ask is you show up to court.’ Kudos to those who work hard to better their communities Women in the workplace, reducing stress and more C1 TECHNOLOGY Streaming service offerings keep growing B6 DEATHS, B4 Darwin Wilbern Baird Frances Elizabeth Corbett Baird George Weston Witherspoon Bernard L. -

Comcast Starts to Deploy 4K/HDR X1 Set-Top

& broadcastingcable.com/next-tv / MAY 22-29, 2017 / 19 CONNECTIONS “That will be BLOG: THE BAUMINATOR a very exciting Comcast Starts to Deploy development in the 4K/HDR X1 Set-Top Box COMCAST HAS BEGUN TO DEPLOY a new whole-home DVR for its X1 plat- marketplace, and form called the XG4 that supports 4K and High Dynamic Range (HDR) video, an industry source confirmed. Jeff Baumgartner is a very positive The Arris-made device, spotted by Light Reading, has popped up on Comcast’s development for X1 device comparison web site. FCC documents shed some more light on the device, including an engineering prototype and a label referencing X1 licensee Cox Communications, about Viacom.” a “XGIv4” 4K set-top. Comcast declined to comment on the XG4, but a person familiar with the product said the operator has — Bob Bakish, CEO of Viacom, speaking at the begun to make it available on a limited basis. JP Morgan Tech, Media and Telecom Conference According to the X1 site, the XG4 sports six tuners and an integrated DVR. At the recent NAB show in about discussions with pay TV providers about Las Vegas, Arris also showed off the MG2, a 4K-capable device that uses the TiVo interface. a sports- and news-free bundle, including Comcast is also testing an IP companion box, called the Xi6, that also supports 4K, but the operator has some Viacom channels, that would sell for $10 not announced when it will be released. Comcast is also deploying the Xi5, a wireless companion box for to $20 per month and launch later this year. -

Southern Planter a MONTHLY JOURNAL DEVOTED TO

. Established 1840. THE Seventieth Year Southern Planter A MONTHLY JOURNAL DEVOTED TO Practical and Progressive Agriculture, Horticulture, Trucking, Live Stock and the Firfeside, OFFICE: 28 NORTH NINTH STREET, RICHMOND, VIRGINIA. THE SOUTHERN PLANTER PUBLISHING COMPANY. Proprietors. J. F. JACKSON, Editor. Vol. 70. OCTOBER, 1909. No. 10. CONTENTS. FARM MANAGEMENT: Oleomargarine Laws -r^. 949 Virginia Duroc Swine Breeders' Association 949 Editorial—Work for the Month 929 Hints to the Boys 949 Value of a First-cIass Pasture 931 Suggested by the Septfrxnber Planter 932 THE POULTRY YXbD: Report of Committed on Soil Investigation Poultry Notes 950 and Experiments in Illinois 933 Virginia i^ultry Show 951 The Winter Cover 936 Simple Fixtures Make Easy Money 7~951 New York State Farming 937 The Farmers' National Congress 952 Preventive for Wheat Smut 938 , The Carmai^ Peach 952 Fertilizers and Manures 938 THE HORSE: Crimson Clover Seeding . .~~T 938 Notes 953 TRUCKING, GARDEN AND ORCHARD: Morgan Stallion in Powhatan 954 Lo ! the King Has Come 954 Editorial—Work for the Mouth 939 The Nomination of Commissioner of Agri- Lime-Sulphur for use Against San Jose culture .'t 955 Scale 940 Virginia State Horticultliral Society 941 MISCELLANEOUS: Should Nurserymen Grow Trees from Care- Ground Limestone 956 fully Selected Scions Only? .* 941 Loudoun Heavy Draft and Agrimtural Af* Paris Green Distributor 943^< sociation . .^ ?57' . •J LIVE STOCK AND DAIRY: The Tenant Question 958 The Tazewell Pair 959 Editorial—The Dairy Inspection Question. .• 944 Good Advice from an Old Virginian—Some Editorial—^Dual Purpose Cows 944 Experience and Suggestions 959 The Dual Purpose Cows 945 Enquirer's Column (Detailed Index p. -

Allen Strickland Williams

ALLEN STRICKLAND WILLIAMS 3723 Tracy Street #1 Los Angeles, CA 90027 (904) 705-6210 [email protected] EXPERIENCE Paradise Creative, Los Angeles, CA Senior Copywriter FEBRUARY 2020 - PRESENT ● Wrote winning pitch decks and social campaign copy for ABC, Amazon Studios, Hulu, Focus Features, Sony Pictures Entertainment, Sony Pictures Animation, Disney+, and Paramount Animation and 20th Century Fox titles. ● Part of social team that won and continues to serve the Amazon Studios brand account. ● Concepted, created, and delivered special shoot scripts. ● Wrote winning submission scripts for creative agency awards. ● Contributed and approved copy for editorial, sizzle reels, and additional agency needs. ● Pitched and won digital concepts for SelvaRey, Bruno Mars’s rum and lifestyle brand. ● Created tone sheets with voice and language guidelines for internal and client use. ● Supervised, edited, and approved Community Manager’s copy to fulfill client requests. ● Part of on-set special shoot writing team for Jumanji: The Next Level. Worked directly with production, studio, and talent. Was cast in a spot written for Uber, which has garnered over 10M combined views on YouTube. ● Assumed Head of Strategy and Head of Digital responsibilities as needed. ● Secured influencers and coordinated with them for executing activations. ● Leveraged connections to bring in $100k of new business. Freelance Copywriter JANUARY 2019 - JANUARY 2020 ● Brainstormed concepts, planned strategy, wrote pitch decks and social campaign copy for Netflix, Amazon Studios, Roadside Attractions, Annapurna Pictures, Neon, and Paramount Pictures titles. Self-Employed, Los Angeles, CA Freelance Copywriter / Comedy Writer / Stand-Up APRIL 2013 - PRESENT ● At Hi5 Agency, brainstormed concepts with Social/Strategy teams and wrote pitch deck copy for Netflix title. -

What's Tv Worth?

WHAT’S TV WORTH? APRIL 2016 1 13 3 We surveyed 1,502 TV consumers… • Age 16 to 74* • Watch at least 5 hours of TV per week • Have broadband at home • U.S. census balanced • Data collection completed in March 2016 • Prior to 2015, the age range for this study was 16-64. On slides with trending to 2014 or 11 earlier, the data is for viewers age 16-64 The New Normal: the average viewer combines multiple TV sources to make their own TV package ELECTRONIC SELL THROUGH SVOD ONLINE CHANNEL OR MCN SCREENS MVPD AND CONNECTORS Live VOD DVR TV Everywhere 2 “What’s TV Worth” tracks how consumers choose, use, and allocate their time across these options Which TV platforms consumers are using, USAGE independently and together The screens viewers watch on, and the devices DEVICES they use to connect their TVs to the internet Which sources viewers see as their “default” – the DEFAULT first thing they turn on when they want to watch Which TV platforms, and which specific brands, VALUE do consumers perceive to be most valuable Which features and attributes drive viewers to use CHOICE certain TV sources over others 3 Executive Summary Overview of Key Findings 4 Is 2016 the year the dust begins to settle? 5 SVOD is emerging as the dominant model for consuming TV Rising Usage High Perceived Value More users are adopting SVOD Perceptions of major SVOD platforms platforms, and many are using more continue to rise, while pay TV is flat than one % RATE “GOOD” use at least one SVOD, OR “EXCELLENT” VALUE 68% up from 47% in 2015 67% Ç Netflix streaming subscribe -

Betting on Ott's Future

BETTING ON OTT’S FUTURE - KEY FACTORS FOR SUCCESS Brought to you by Viaccess-Orca Authored by: Patricia Frith, Founder and President, Patricia Frith Marketing It’s smarter, it’s safer. It’s VO. Betting on OTT’s Future Executive Summary Whether you’re transitioning your traditional television business or launching a brand new OTT service, you’ve been affected by the rapid acceleration of the OTT business over the past three years. Though some media companies are seizing opportunities to off-set shrinking Pay-TV revenues at home by taking advantage of the remaining growth areas for Pay-TV, the strategy seems to be one of diminishing returns as OTT continues to flourish and mature into a profitable and sustainable business. The barriers to entry are becoming more and more surmountable, and those who don’t lose sight of what consumers want will stand to win big. This whitepaper offers some observations and recommendations for charting the best course for your business. If there ever was an inflection point when OTT’s future competency became somewhat of a foregone conclusion, we’d have to point to 2015. Sure, Netflix and Amazon Prime were already soaring by this point, but that was the year when major media networks decided to launch direct-to-consumer streaming services like HBO Now, CBS All Access and others. It was also the year of bold initiatives like putting a newly imagined version of “Star Trek” on CBS All Access rather than the mother broadcast network. It was also in 2015 that Amazon introduced its download capability that allowed offline viewing, and mobile providers unveiled plans for unmetered SVOD streaming.