Encoding Monsters: “Ontology of the Enemy” and Containment of the Unknown in Role-Playing Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campaign Information

Arak and Gwydion (Some Thoughts on the Shadow Elves' History) By R. Sweeney Gwydion isn't a 'real' demon, but rather a creature of great power from the plane of shadow. Gwydion's evil was his enslavement of the ShadowElves. His torment is his betrayal by Arak. Unlike Vecna, he was not on the prime and could only be 'trapped' because he was trying to follow the Shadow Elves into RL. (Presumably to kill them or re-enslave them). I wonder what Arak was thinking, however. Would there be anyplace he could take the Shadow elves into exile where Gwydion could not follow? Did he think he could hide from such a powerful creature? Gwydion must have had an enemy. A sibling perhaps. The Shadow Elves must have acted as some sort of armed forces for him. Arak must have believed that if Gwydion suddenly found himself without his Slaves, he would have been destroyed by his rivals. However, there other.. less satisfying, perhaps, ways of re-writing ShadowElf history. Gwydion, the shadow-being, falls 'in love' with an elf from some other world. They mate, bear children. Woman dies, Gwydion takes his children and their children as slaves. Millenia pass. Arak was Gwydion's favorite. Perhaps, Gwydion had mated with one of the Shadow elves of unsurpassed beauty and begat Arak. Thus, he set his son above all the other slaves. Arak, however, desired more than to be the head of the slaves. He managed to betray his father to his enemies. Arak had intended patricide. He was going to take away Gwydion's protective armed forces, leaving him vulnerable to attack by his other enemies. -

SILVER AGE SENTINELS (D20)

Talking Up Our Products With the weekly influx of new roleplaying titles, it’s almost impossible to keep track of every product in every RPG line in the adventure games industry. To help you organize our titles and to aid customers in finding information about their favorite products, we’ve designed a set of point-of-purchase dividers. These hard-plastic cards are much like the category dividers often used in music stores, but they’re specially designed as a marketing tool for hobby stores. Each card features the name of one of our RPG lines printed prominently at the top, and goes on to give basic information on the mechanics and setting of the game, special features that distinguish it from other RPGs, and the most popular and useful supplements available. The dividers promote the sale of backlist items as well as new products, since they help customers identify the titles they need most and remind buyers to keep them in stock. Our dividers can be placed in many ways. These are just a few of the ideas we’ve come up with: •A divider can be placed inside the front cover or behind the newest release in a line if the book is displayed full-face on a tilted backboard or book prop. Since the cards 1 are 11 /2 inches tall, the line’s title will be visible within or in back of the book. When a customer picks the RPG up to page through it, the informational text is uncovered. The card also works as a restocking reminder when the book sells. -

Copyright by William Joseph Taylor 2009

Copyright by William Joseph Taylor 2009 The Dissertation Committee for William Joseph Taylor certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘That country beyond the Humber’: The English North, Regionalism, and the Negotiation of Nation in Medieval English Literature Committee: _________________________ Elizabeth Scala, co-supervisor _________________________ Daniel Birkholz, co-supervisor _________________________ Marjorie Curry Woods _________________________ Mary Blockley _________________________ Geraldine Heng ‘That country beyond the Humber’: The English North, Regionalism, and the Negotiation of Nation in Medieval English Literature by William Joseph Taylor, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2009 For Laura Poi le vidi in un carro trïumfale, Laurëa mia con suoi santi atti schifi sedersi in parte, et cantar dolcemente. (Petrarch, Canzoniere CCXXV) Acknowledgements A number of individuals have supported me throughout the writing of this dissertation and in my graduate work. It gives me great pleasure to acknowledge their contributions here. First, I want to thank my two advisors and mentors, Elizabeth Scala and Daniel Birkholz. Liz Scala, for several years now, has provided me a steady balance of tough love, rigorous expectation, and critical acumen for which I can never repay. Her advice, her tutelage, and her direction were vital to my development as a scholar and to the success I have already known in academia. Months of dissertation anxiety and the crafting of a far-fetched project were met by Liz’s emphatically simple suggestion: “Why don’t you work on the North?” She could only ask this because she visited each of my professors individually to inquire as to my interests in seminars, and her inquiry testifies to her dedication as an advisor and teacher. -

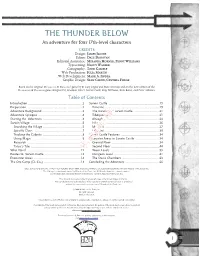

Thunder Below

THE THUNDER BELOW An adventure for four 17th-level characters CREDITS Design: JAMES JACOBS Editor: DALE DONOVAN Editorial Assistance: MIRANDA HORNER, PENNY WILLIAMS Typesetting: NANCY WALKER Cartography: TODD GAMBLE Web Production: JULIA MARTIN Web Development: MARK A. JINDRA Graphic Design: SEAN GLENN, CYNTHIA FLIEGE Based on the original DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® game by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson and on the new edition of the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS game designed by Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Rich Baker, and Peter Adkison. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................2 Sarwin Castle ..............................................................19 Preparation ...................................................................2 Timeline ..................................................................19 Adventure Background .................................................2 The Invaders of Sarwin Castle ...............................21 Adventure Synopsis ......................................................4 Tiboquoboc..............................................................21 Starting the Adventure ................................................4 Alraugh ....................................................................24 Sarwin Village ...............................................................5 Irika .........................................................................26 Searching the Village ................................................5 Muraxus ..................................................................27 -

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

Martial Arts

Stock #37-2614 COVER ART INTERIOR ART CONTENTS Bob Stevlic Greg Hyland JupiterImages FROM THE EDITOR . 3 HARDCORE . 4 by Stephen Dedman N HIS THE THREE BROTHERS I T SCHOOLS OF MARTIAL ARTS . 13 by Alan Leddon ISSUE FIGHT WHILE IN FLIGHT . 17 by Kelly Pedersen The righteous battle never ends – certainly not with this, the Martial Arts issue of Pyramid. With two new adventures, eight INSTANT TOURNAMENT. 21 new styles for GURPS Martial Arts, and other dojo-powered delights, this issue is sure to have something to add punch to THE GROOM OF your two-fisted campaigns. THE SPIDER PRINCESS . 24 Heroes need to get Hardcore in a modern-day adventure by J. Edward Tremlett centered on illegal (and immoral) underground fighting. Do the PCs have the guts and skill to break up this operation? RANDOM THOUGHT TABLE: NO BLOOD, What started as a school of martial arts run by three broth- NO GUTS, NO PROBLEM!. 35 ers has splintered into three different schools – each with its by Steven Marsh, Pyramid Editor own focus. Sadly, although the schools teach effective skills, they do not teach particularly honorable ones . Learn the ODDS AND ENDS . 37 secrets of this family business, plus three GURPS Martial Arts styles, in The Three Brothers School of Martial Arts. APPENDIX Z: Many martial-arts students have been criticized for having THE CRUMBLING GROUND . 38 their heads in the clouds, but Fight While in Flight shows the other side of this admonition. These five GURPS Martial Arts ABOUT GURPS . 40 styles are designed for fighters looking to make best use of their ability to fly, jump, or aerially maneuver. -

Nither Man Nor Beast

Tablu of Contunts Introduction ................... ..2 Welcome to the Horror ...... ...2 Maintaining the Mystery ....... .....3 The Good Ship Sunset Empires. ..........4 The Good Ship Sunset Empires. ..........5 TheCrew .................. .....8 Life Under Sail. ... 10 Dr. Fran’s Island .... ... 17 Awakening ........ .17 A Tour of the Island. .... 18 Adventures in Paradise . ....23 Dr. Fran’s Manor. .......... ...28 Key to the Manor. ......... .... 28 The Members of the Household. > .33 Manor Life. ............... , .34 The Monastery of the Lost. .. ...45 Getting There ......... ....45 The Monastery ........ .... 45 The Brethren. ........... ....52 Reaching the Monastery ... ....55 Finale. ................. ...59 A Treachery Revealed. .. ....59 Akanga’s War ......... .... 59 Escape From the Island. .............. .63 Wrapping_- - Things- Up ..................64 Theshanty ........................ 12 The Broken Ones: A Quick Guide ......21 Markov’s Journal.. ................. .33Sample file The Order of the Guardians .......... .46 The History of Markovia ..............48 The Table of Life. ................... .51 Crudits TSR, Inc. TSR Ltd. Jeff Grubb Design: 20 1 Sheridan Springs-- 120 Church End, Editing: John D. Rateliff Lake Geneva Cherry Hinton Project Coordination: Harold Johnson 53147 Cambridge CBl 3LB Cover Art: Larry Elmore WI Interior Art: Valerie Valusek & Karolyn Guldan U.S.A United Kingdom Additional Art: Mark Nelson, Ned Dameron, & Stephan Fabian Bruce Zamjahn Art Direction: 9499 Cartography: Robin Raab & Roy M. Boholst Typesetting: Gaye O’Keefe & Tracey Isler ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, ADGD, DRAGONLANCE, and RAVENLOFT are registered trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. The TSR logo is a trademark owned by TSR, Inc. All TSR characters, character names, and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. 01995 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Made in the U.S.A. -

Epic-Level Prestige Class Progressions a Web Enhancement for the Epic Level Handbook

Epic-Level Prestige Class Progressions A Web Enhancement for the Epic Level Handbook The Epic Level Handbook provides epic-level progres- ucts: specifically, Defenders of the Faith, Manual of the sions—that is, information on the powers, abilities, and Planes, Masters of the Wild, Song & Silence, Sword & Fist, bonus feats gained by epic-level characters—for all 11 and Tome & Blood. While this doesn’t encompass every classes presented in the Player’s Handbook, as well as the prestige class presented to date (that would require an six prestige classes detailed in the DUNGEON MASTER’s entire book all to itself!), it gives DMs a wide range of Guide. But with the vast number of prestige classes pub- examples that should help them build other epic pro- lished in other DUNGEONS & DRAGONS®products, the gressions as needed. Simply find a class (either here or Epic Level Handbook couldn’t address the needs of every in the Epic Level Handbook) that’s roughly similar to your single epic-level character. chosen prestige class and start there. That’s where this web enhancement comes in. Here, To use this web enhancement, you should already you’ll find epic-level progressions for a full two dozen have the Epic Level Handbook accessory by Andy Collins, prestige classes drawn from various core D&D prod- Bruce R. Cordell, and Thomas M. Reid. This bonus material is brought to you by the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS official website: <www.wizards.com/dnd>. Credits You’ll note that every prestige class included in this enhancement is a 10-level class. -

Lovecraft Research Paper Final Draft

Nagelvoort 1 Chris Nagelvoort Professor Walsh Humanities Core H1CS 13 June 2020 Becoming Anti-Human: How Lovecraftian Horror Philosophically Deconstructs Otherness The most horrifying monster is change. Having the comfort and consistency of normality be thrust into the foreign landscape of difference can be petrifying. The dormant mind can lose its sense of self, security, and, worst of all, control. In the horror genre, this is no different. Monsters are frightening because of the difference they impose on us and our identity. Imagining a world ruled by a zombie apocalypse or a ravenous vampire feasting at night may seem unobtrusive, but when the rabid ghoul trespasses the border of detached fiction into the interior of one’s identity, the cliche skeleton seems almost an afterthought. Much more terrifying than the grotesqueness or typicality of these horror villains is how they can turn one’s sense of self and control inside out. It invites the elusive glance inward, asking the subject to wonder if their pillars of psychological safety—identity, family, belief system, home—are very safe at all. This fear of something different is compartmentalized by the psyche as something so alien, so invasive, that it must be something Other. This effect is explored by the stories of Howard Philips Lovecraft, a horror writer whose stories are so bizarre that the average reader is stripped of all their preconceptions about reality and even their sense of self. This special subgenre of horror was pioneered by Lovecraft and is famously called “Lovecraftian horror” but is well known today as cosmic horror: A mesh of horror and science fiction that “erodes presumptions about the nature of reality” (Cardin 273). -

Bram Stoker Award Is Awarded by the Horror Writers Association for “Superior Achievement” in Horror Writing

1 The Midnight Society Kaitlin Conner Readers’ Advisory Librarian, NoveList Gregg Winsor Reference Librarian, Johnson County Library, Kansas Autumn Winters Recommendations Lead, NoveList 2 libraryreads.org 3 Speculative Fiction Science Fiction Fantasy Horror What if our scientific theories are real? What if magic or magical creatures exist? What if our nightmares are real? 4 The Pull of the Grave 5 6 “It shows us that the control we believe we have is purely illusory, and that every moment we teeter on chaos and oblivion.” -Clive Barker Introduction to “Scared Stiff: Tales of Sex and Death” by Ramsey Campbell, 1987. 7 ‘Visceral’ Fiction 8 History of the Genre 9 Gothic Horror in the 18th Century A significant amount of horror fiction of this era was marketed towards a female audience, a typical scenario being a resourceful female menaced in a gloomy castle. 1764 1796 1797 10 19th Century Horror The gothic tradition turns to the genre modern readers call horror and many foundational characters are born. 1818 1839 1886 1897 11 Early 20th Century Pulp Fiction Pulp magazines emerged to give more genre writers an outlet. H.P. Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, and Robert Bloch, among many others, published stories in magazines. 1928 1931 1937 12 Pre-Modern Era The real-life horrors of World War II and the looming paranoia and menace of the Cold War usher in a new generation as horror novels gain mainstream acceptability. 1954 1959 1967 1974 13 14 NoveList Appeals and Themes 15 Menacing Suspenseful Bleak Creepy Brooding Gruesome Atmospheric Compelling Darkly Strong female humorous Flawed Menacing Disturbing Intensifying Flawed Moody Violent 16 Cursed! Possessed! Trapped! P l Childhood trauma o Don’t go in there! t Evil transformations Witchcraft and the occult Zombie apocalypse 17 Trapped! Think isolated cabins, Arctic research bases, submarines, graves, or elevators. -

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe Title

The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe Title: The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Author: Daniel Defoe CHAPTER I—START IN LIFE I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull. He got a good estate by merchandise, and leaving off his trade, lived afterwards at York, from whence he had married my mother, whose relations were named Robinson, a very good family in that country, and from whom I was called Robinson Kreutznaer; but, by the usual corruption of words in England, we are now called—nay we call ourselves and write our name—Crusoe; and so my companions always called me. I had two elder brothers, one of whom was lieutenant-colonel to an English regiment of foot in Flanders, formerly commanded by the famous Colonel Lockhart, and was killed at the battle near Dunkirk against the Spaniards. What became of my second brother I never knew, any more than my father or mother knew what became of me. Being the third son of the family and not bred to any trade, my head began to be filled very early with rambling thoughts. My father, who was very ancient, had given me a competent share of learning, as far as house-education and a country free school generally go, and designed me for the law; but I would be satisfied with nothing but going to sea; and my inclination to this led me so strongly against the will, nay, the commands of my father, and against all the entreaties and persuasions of my mother and other friends, that there seemed to be something fatal in that propensity of nature, tending directly to the life of misery which was to befall me. -

From Rolling to Reading an Analysis of the Adaptation of Narrative Between Role-Playing Games and Novels

From Rolling to Reading An Analysis of the Adaptation of Narrative Between Role-Playing Games and Novels Nikolai Bjädefors Butler 5/17/2018 Lunds universitet Nikolai Bjädefors Butler Masterprogram Litteratur – kultur - medier LIVR07 Handledare Alexander Bareis 2018-05-29 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................2 Background – What is a Role-Playing Game? .....................................................................4 Purpose and Problem ..........................................................................................................6 Literature ............................................................................................................................8 Method ............................................................................................................................. 10 Analysis ............................................................................................................................... 11 From Rulings to Readings................................................................................................. 11 From Players to Print ........................................................................................................ 19 From Metagaming to Metafiction ..................................................................................... 23 From Page to Table..........................................................................................................