Eoghain Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

The New Cosmic Horror: a Genre Molded by Tabletop Roleplaying Fiction Editor Games and Postmodern Horror

315 Winter 2016 Editor Chris Pak SFRA [email protected] A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association Nonfiction Editor Dominick Grace In this issue Brescia University College, 1285 Western Rd, London ON, N6G 3R4, Canada SFRA Review Business phone: 519-432-8353 ext. 28244. Prospect ............................................................................................................................2 [email protected] Assistant Nonfiction Editor SFRA Business Kevin Pinkham The New SFRA Website ..............................................................................................2 College of Arts and Sciences, Ny- “It’s Alive!” ........................................................................................................................3 ack College, 1 South Boulevard, Nyack, NY 10960, phone: 845- Science Fiction and the Medical Humanities ....................................................3 675-4526845-675-4526. [email protected] Feature 101 The New Cosmic Horror: A Genre Molded by Tabletop Roleplaying Fiction Editor Games and Postmodern Horror ..............................................................................7 Jeremy Brett Cushing Memorial Library and Sentience in Science Fiction 101 ......................................................................... 14 Archives, Texas A&M University, Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, 5000 TAMU College Nonfiction Reviews Station, TX 77843. Black and Brown Planets: The Politics of Race in Science Fiction ........ 19 -

6.4. of Goths and Salmons: a Practice-Basedeexploration of Subcultural Enactments in 1980S Milan

6.4. Of goths and salmons: A practice-basedeExploration of subcultural enactments in 1980s Milan Simone Tosoni1 Abstract The present paper explores, for the first time, the Italian appropriations of British goth in Italy, and in particular in the 1980s in Milan. Adopting a practice-based approach and a theoretical framework based on the STS-derived concept of “enactment”, it aims at highlighting the coexistence of different forms of subcultural belonging. In particular, it identifies three main enactments of goth in the 1980s in Milan: the activist enactment introduced by the collective Creature Simili (Kindred Creatures); the enactment of the alternative music clubs and disco scene spread throughout northern Italy; and a third one, where participants enacted dark alone or in small groups. While these three different variations of goth had the same canon of subcultural resources in common (music, style, patterns of cultural consumption), they differed under relevant points of view, such as forms of socialization, their stance on political activism, identity construction processes and even the relationship with urban space. Yet, contrary to the stress on individual differences typical of post-subcultural theories, the Milanese variations of goth appear to have been socially shared and connected to participation in different and specific sets of social practices of subcultural enactment. Keywords: goth, subculture, enactment, practices, canon, scene, 1980s. For academic research, the spectacular subcultures (Hebdidge, 1979) in the 1980s in Italy are essentially uncharted waters (Tosoni, 2015). Yet, the topic deserves much more sustained attention. Some of these spectacular youth expressions, in fact, emerged in Italy as a peculiarity of the country, and are still almost ignored in the international debate. -

How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia Christopher Ludden McDaid College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McDaid, Christopher Ludden, "Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625918. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4bnb-dq93 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fufillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christopher Ludden McDaid 1994 Approval Sheet This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts r Lucfclen MoEfaid Approved, October 1994 _______________________ ixJLt James Axtell John Sel James Whittenourg ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................................. -

Noel Carroll Source: the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol

The Nature of Horror Author(s): Noel Carroll Source: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Autumn, 1987), pp. 51-59 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/431308 Accessed: 12/05/2010 10:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The American Society for Aesthetics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. http://www.jstor.org NOEL CARROLL The Nature of Horror FOR NEARLY A DECADE and a half, perhaps espe- Romero's Night of the Living Dead or Scott's cially in America, horror has flourished as a Alien. -

Don Banks David Morgan Peter Racine Fricker Violin Concertos

SRCD.276 STEREO ADD Don Banks PETER RACINE FRICKER (1920-1990) David Morgan Concerto for Violin and small Orchestra Op. 11 (1950) (23’25”) 1 1st Movement: Con moto (9’42”) 2 2nd Movement: Andante (5’27”) Peter Racine Fricker 3 3rd Movement: Allegro vivo (8’16”) DAVID MORGAN (1933-1988) Violin Concerto (1966) * (26’02”) 4 1st Movement: Lento – Moderato cantabile – Alla Marcia (11’55”) 5 2nd Movement: Presto energico ma leggieramente (5’07”) Violin Concertos 6 3rd Movement: Lento – Allegro deciso – Con fuoco (9’00”) DON BANKS (1923-1980) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1968) (26’55”) 7 1st Movement: Lento – Allegro (9’42”) 8 2nd Movement: Andante cantabile (9’36”) 9 3rd Movement: Risoluto (7’37”) (76’26”) Yfrah Neaman, violin * Erich Gruenberg, violin Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Norman Del Mar * Vernon Handley The above individual timings will normally each include two pauses. One before the beginning of each movement or work, and one after the end. Erich Gruenberg • Yfrah Neaman ൿ 1974 * ൿ 1978 The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. This compilation and the digital remastering ൿ 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra © 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita Vernon Handley • Norman Del Mar by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK PETER RACINE FRICKER was born in Ealing on 5 September 1920. His middle name came from his great-grandmother, a direct descendant of the French dramatist. -

Martial Arts

Stock #37-2614 COVER ART INTERIOR ART CONTENTS Bob Stevlic Greg Hyland JupiterImages FROM THE EDITOR . 3 HARDCORE . 4 by Stephen Dedman N HIS THE THREE BROTHERS I T SCHOOLS OF MARTIAL ARTS . 13 by Alan Leddon ISSUE FIGHT WHILE IN FLIGHT . 17 by Kelly Pedersen The righteous battle never ends – certainly not with this, the Martial Arts issue of Pyramid. With two new adventures, eight INSTANT TOURNAMENT. 21 new styles for GURPS Martial Arts, and other dojo-powered delights, this issue is sure to have something to add punch to THE GROOM OF your two-fisted campaigns. THE SPIDER PRINCESS . 24 Heroes need to get Hardcore in a modern-day adventure by J. Edward Tremlett centered on illegal (and immoral) underground fighting. Do the PCs have the guts and skill to break up this operation? RANDOM THOUGHT TABLE: NO BLOOD, What started as a school of martial arts run by three broth- NO GUTS, NO PROBLEM!. 35 ers has splintered into three different schools – each with its by Steven Marsh, Pyramid Editor own focus. Sadly, although the schools teach effective skills, they do not teach particularly honorable ones . Learn the ODDS AND ENDS . 37 secrets of this family business, plus three GURPS Martial Arts styles, in The Three Brothers School of Martial Arts. APPENDIX Z: Many martial-arts students have been criticized for having THE CRUMBLING GROUND . 38 their heads in the clouds, but Fight While in Flight shows the other side of this admonition. These five GURPS Martial Arts ABOUT GURPS . 40 styles are designed for fighters looking to make best use of their ability to fly, jump, or aerially maneuver. -

LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest

LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest On the forum, I gave you the following assignment: Read the first 5 pages of Boneshaker by Cherie Priest. List the Steampunk elements you find. Then list the ESSENTIAL Steampunk genre elements, and then the Character descriptions, then setting Your chart will look something like this: STEAMPUNK ...................... ESSENTIAL ...................CHARACTER ...........SETTING ELEMENTS ......................... ELEMENTS.....................ELEMENTS...............ELEMENTS black overcoat black overcoat 11 crooked stairs 11 crooked stairs and so on you can find Boneshaker here at Amazon The table part didn’t come out very well so here’s a better version. I added the word “ALL” to the column labels because I wanted you to understand that in those columns I’m not looking for any specific elements other than those labeled. For instance, under “CHARACTER ELEMENTS (ALL)” give all the character elements you find, not just elements pertaining to the Steampunk genre. STEAMPUNK ESSENTIAL CHARACTER SETTING ELEMENTS (ALL) STEAMPUNK ELEMENTS ELEMENTS (ALL) ELEMENTS (ALL) Black overcoat Black overcoat 11 crooked stairs 11 crooked stairs Goth, Gadgets & Grunge: Steampunk Stories with Style!© By Pat Hauldren LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest / 2 If you’ll notice on the link I provided for Boneshaker at Amazon.com, it’s listed as “ (Sci Fi Essential Books) “ and baby, that’s where *I* want to be! I couldn’t find a specific definition for exactly what that term meant at Amazon.com, but just from the term itself, you can tell it’s the list of books that, while aren’t classics yet, are becoming so for various reasons. -

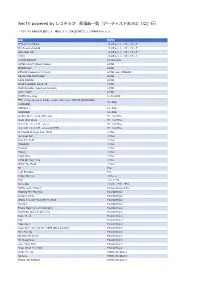

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by Leeds Beckett Repository The Strange and Spooky Battle over Bats and Black Dresses: The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture Professor Karl Spracklen (Leeds Metropolitan University, UK) and Beverley Spracklen (Independent Scholar) Lead Author Contact Details: Professor Karl Spracklen Carnegie Faculty Leeds Metropolitan University Cavendish Hall Headingley Campus Leeds LS6 3QU 44 (0)113 812 3608 [email protected] Abstract From counter culture to subculture to the ubiquity of every black-clad wannabe vampire hanging around the centre of Western cities, Goth has transcended a musical style to become a part of everyday leisure and popular culture. The music’s cultural terrain has been extensively mapped in the first decade of this century. In this paper we examine the phenomenon of the Whitby Goth Weekend, a modern Goth music festival, which has contributed to (and has been altered by) the heritage tourism marketing of Whitby as the holiday resort of Dracula (the place where Bram Stoker imagined the Vampire Count arriving one dark and stormy night). We examine marketing literature and websites that sell Whitby as a spooky town, and suggest that this strategy has driven the success of the Goth festival. We explore the development of the festival and the politics of its ownership, and its increasing visibility as a mainstream tourist destination for those who want to dress up for the weekend. By interviewing Goths from the north of England, we suggest that the mainstreaming of the festival has led to it becoming less attractive to those more established, older Goths who see the subculture’s authenticity as being rooted in the post-punk era, and who believe Goth subculture should be something one lives full-time. -

Lovecraft Research Paper Final Draft

Nagelvoort 1 Chris Nagelvoort Professor Walsh Humanities Core H1CS 13 June 2020 Becoming Anti-Human: How Lovecraftian Horror Philosophically Deconstructs Otherness The most horrifying monster is change. Having the comfort and consistency of normality be thrust into the foreign landscape of difference can be petrifying. The dormant mind can lose its sense of self, security, and, worst of all, control. In the horror genre, this is no different. Monsters are frightening because of the difference they impose on us and our identity. Imagining a world ruled by a zombie apocalypse or a ravenous vampire feasting at night may seem unobtrusive, but when the rabid ghoul trespasses the border of detached fiction into the interior of one’s identity, the cliche skeleton seems almost an afterthought. Much more terrifying than the grotesqueness or typicality of these horror villains is how they can turn one’s sense of self and control inside out. It invites the elusive glance inward, asking the subject to wonder if their pillars of psychological safety—identity, family, belief system, home—are very safe at all. This fear of something different is compartmentalized by the psyche as something so alien, so invasive, that it must be something Other. This effect is explored by the stories of Howard Philips Lovecraft, a horror writer whose stories are so bizarre that the average reader is stripped of all their preconceptions about reality and even their sense of self. This special subgenre of horror was pioneered by Lovecraft and is famously called “Lovecraftian horror” but is well known today as cosmic horror: A mesh of horror and science fiction that “erodes presumptions about the nature of reality” (Cardin 273). -

Xavier Aldana Reyes, 'The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror

1 Originally published in/as: Xavier Aldana Reyes, ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’, Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies, 5.2 (2017), 229–44. DOI link: 10.1386/jicms.5.2.229_1 Title: ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’ Author: Xavier Aldana Reyes Affiliation: Manchester Metropolitan University Abstract: Dario Argento is the best-known living Italian horror director, but despite this his career is perceived to be at an all-time low. I propose that the nadir of Argento’s filmography coincides, in part, with his embrace of the gothic adaptation and that at least two of his late films, The Phantom of the Opera (1998) and Dracula 3D (2012), are born out of the tensions between his desire to achieve auteur status by choosing respectable and literary sources as his primary material and the bloody and excessive nature of the product that he has come to be known for. My contention is that to understand the role that these films play within the director’s oeuvre, as well as their negative reception among critics, it is crucial to consider how they negotiate the dichotomy between the positive critical discourse currently surrounding gothic cinema and the negative one applied to visceral horror. Keywords: Dario Argento, Gothic, adaptation, horror, cultural capital, auteurism, Dracula, Phantom of the Opera Dario Argento is, arguably, the best-known living Italian horror director.