Noel Carroll Source: the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Banks David Morgan Peter Racine Fricker Violin Concertos

SRCD.276 STEREO ADD Don Banks PETER RACINE FRICKER (1920-1990) David Morgan Concerto for Violin and small Orchestra Op. 11 (1950) (23’25”) 1 1st Movement: Con moto (9’42”) 2 2nd Movement: Andante (5’27”) Peter Racine Fricker 3 3rd Movement: Allegro vivo (8’16”) DAVID MORGAN (1933-1988) Violin Concerto (1966) * (26’02”) 4 1st Movement: Lento – Moderato cantabile – Alla Marcia (11’55”) 5 2nd Movement: Presto energico ma leggieramente (5’07”) Violin Concertos 6 3rd Movement: Lento – Allegro deciso – Con fuoco (9’00”) DON BANKS (1923-1980) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1968) (26’55”) 7 1st Movement: Lento – Allegro (9’42”) 8 2nd Movement: Andante cantabile (9’36”) 9 3rd Movement: Risoluto (7’37”) (76’26”) Yfrah Neaman, violin * Erich Gruenberg, violin Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Norman Del Mar * Vernon Handley The above individual timings will normally each include two pauses. One before the beginning of each movement or work, and one after the end. Erich Gruenberg • Yfrah Neaman ൿ 1974 * ൿ 1978 The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. This compilation and the digital remastering ൿ 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra © 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita Vernon Handley • Norman Del Mar by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK PETER RACINE FRICKER was born in Ealing on 5 September 1920. His middle name came from his great-grandmother, a direct descendant of the French dramatist. -

(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” By

“(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” By Jennifer M. Abercrombie Foster @ Copyright 2016 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Yajaira Padilla ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Verónica Garibotto ________________________________ Jorge Pérez ________________________________ Vicky Unruh ________________________________ Hannah Britton ________________________________ Magalí Rabasa Date Defended: May 3, 2016 ii The Dissertation Committee for Jennifer M. Abercrombie Foster certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Yajaira Padilla ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Verónica Garibotto Date approved: May 9, 2016 iii Abstract Since the turn of the 20th century many writers, playwrights, and poets in Central America and the Hispanic Caribbean have published fantastic, gritty, and oftentimes unsettling stories of ghosts, anthropomorphic animals, zoomorphic humans, and uncanny spaces. These unexpected encounters and strange entities are an embodiment of muddled boundaries and -

Le Studio Hammer, Laboratoire De L'horreur Moderne

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 12 | 2016 Mapping gender. Old images ; new figures Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.8195 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference David Roche, “Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne ”, Miranda [Online], 12 | 2016, Online since 29 February 2016, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.8195 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne 1 Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche 1 This exciting conference1 was the first entirely devoted to the British exploitation film studio in France. Though the studio had existed since the mid-1940s (after a few productions in the mid-1930s), it gained notoriety in the mid-1950s with a series of readaptations of classic -

And Nineteenth-Century Rake Character to Depictions Of

TRACING THE ORIGINS OF THE EIGHTEENTH- AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY RAKE CHARACTER TO DEPICTIONS OF THE MODERN MONSTER COURTNEY A. CONRAD Bachelor of Arts in English Cleveland State University December 2011 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY MAY 2019 We hereby approve this thesis For COURTNEY A. CONRAD Candidate for the Master of Arts in English Literature degree for the Department of ENGLISH And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by ___________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Rachel Carnell __________________________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Member, Dr. Frederick Karem __________________________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Member, Dr. Gary Dyer __________________________________________ Department & Date Student’s Date of Defense: May 3, 2019 TRACING THE ORIGINS OF THE EIGHTEENTH- AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY RAKE CHARACTER TO DEPICTIONS OF THE MODERN MONSTER COURTNEY A. CONRAD ABSTRACT While critics and authors alike have deemed the eighteenth- and nineteenth- century literary rake figure as a “monster” and a “devil,” scholars have rarely drawn the same connections between monsters to rakes. Even as critics have decidedly characterized iconic monsters like Victor Frankenstein and Dracula as rapists or seducers, they oftentimes do not make the distinction -

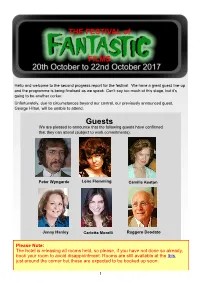

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend (Subject to Work Commitments)

Hello and welcome to the second progress report for the festival. We have a great guest line-up and the programme is being finalised as we speak. Can’t say too much at this stage, but it’s going to be another corker. Unfortunately, due to circumstances beyond our control, our previously announced guest, George Hilton, will be unable to attend. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend (subject to work commitments). Peter Wyngarde Lone Flemming Camille Keaton Jenny Hanley Carlotta Morelli Ruggero Deodato Please Note: The hotel is releasing all rooms held, so please, if you have not done so already, book your room to avoid disappointment. Rooms are still available at the Ibis, just around the corner but these are expected to be booked up soon. 1 Welcome to the Festival : Once again the Festival approaches and as always it is great looking forward to meeting old friends again and talking films. The main topic of conversation so far this year seems to be the imminent arrival of some more classic Hammer films on Blu Ray, at long last. Like so many of you, I am very much looking forward to these and it is fortuitous that this year Jenny Hanley is making a return visit to our festival, just as her Hammer magnum opus with Christopher Lee and Dennis Waterman, Scars of Dracula is on the list of new blu rays being released. I am having to face the inevitable question of how much longer I can go on, but that is not your problem. -

Le Studio Hammer, Laboratoire De L'horreur Moderne (10-12 Juin 2015)

Colloque : Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne (10-12 juin 2015) Comité organisateur : Gilles Menegaldo, Université de Poitiers, [email protected] ; Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris, Université Paris Ouest, [email protected], Université Paris 3, Mélanie Boissonneau, Université Paris 3/IRCAV, [email protected]. Lieux : Université Paris Ouest Nanterre (10 juin), Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle, Centre Censier, (11 juin), Cité Internationale, Fondation Lucien Paye (12 juin) Au moment de la réédition de la célèbre revue Midi-Minuit Fantastique (Rouge Profond) et dans une période où le genre fantastique/horrifique est particulièrement dynamique tant au cinéma que dans les séries télévisées, il semble opportun de faire retour sur le rôle joué par la Hammer Films, studio indépendant britannique qui, vingt ans après Universal, a fait revivre les grandes figures mythiques (Dracula, Frankenstein, la Momie, le Loup-garou etc.) en leur donnant une incarnation modernisée plus conforme à l’évolution de la société et des mœurs en Angleterre en particulier. Le studio Hammer est créé en 1934 par Enrique Carreras et William Hinds. Après des débuts assez modestes mais où déjà un style s’affirme, en particulier dans des films de SFcomme Le triangle à quatre côtés (1953), et The Quatermass Experiment (1955), le studio connaît un grand succès avec The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) suivi peu après parHorror of Dracula (1958), tous deux réalisés par Terence Fisher qui va imprimer sa marque, grâce aussi à des acteurs comme Christopher Lee et Peter Cushing, futures icônes du cinéma d’horreur. Le studio produit entre 1955 et 1979 près de 150 films et aussi deux séries télévisées à succès. -

For More Than Seventy Years the Horror Film Has

WE BELONG DEAD FEARBOOK Covers by David Brooks Inside Back Cover ‘Bride of McNaughtonstein’ starring Eric McNaughton & Oxana Timanovskaya! by Woody Welch Published by Buzzy-Krotik Productions All artwork and articles are copyright their authors. Articles and artwork always welcome on horror fi lms from the silents to the 1970’s. Editor Eric McNaughton Design and Layout Steve Kirkham - Tree Frog Communication 01245 445377 Typeset by Oxana Timanovskaya Printed by Sussex Print Services, Seaford We Belong Dead 28 Rugby Road, Brighton. BN1 6EB. East Sussex. UK [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/#!/groups/106038226186628/ We are such stuff as dreams are made of. Contributors to the Fearbook: Darrell Buxton * Darren Allison * Daniel Auty * Gary Sherratt Neil Ogley * Garry McKenzie * Tim Greaves * Dan Gale * David Whitehead Andy Giblin * David Brooks * Gary Holmes * Neil Barrow Artwork by Dave Brooks * Woody Welch * Richard Williams Photos/Illustrations Courtesy of Steve Kirkham This issue is dedicated to all the wonderful artists and writers, past and present, that make We Belong Dead the fantastic magazine it now is. As I started to trawl through those back issues to chose the articles I soon realised that even with 120 pages there wasn’t going to be enough room to include everything. I have Welcome... tried to select an ecleectic mix of articles, some in depth, some short capsules; some serious, some silly. am delighted to welcome all you fans of the classic age of horror It was a hard decision as to what to include and inevitably some wonderful to this first ever We Belong Dead Fearbook! Since its return pieces had to be left out - Neil I from the dead in March 2013, after an absence of some Ogley’s look at the career 16 years, WBD has proved very popular with fans. -

Eoghain Hamilton

Edited by Eoghain Hamilton The Gothic - Probing the Boundaries Critical Issues Critical Issues Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Dr Daniel Riha Advisory Board Dr Alejandro Cervantes-Carson Dr Peter Mario Kreuter Professor Margaret Chatterjee Martin McGoldrick Dr Wayne Cristaudo Revd Stephen Morris Mira Crouch Professor John Parry Dr Phil Fitzsimmons Paul Reynolds Professor Asa Kasher Professor Peter Twohig Owen Kelly Professor S Ram Vemuri Revd Dr Kenneth Wilson, O.B.E A Critical Issues research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/critical-issues/ The Ethos Hub ‘The Gothic’ 2012 The Gothic - Probing the Boundaries Edited by Eoghain Hamilton Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-088-7 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2012. First Edition. Table -

Constructions of Femininity in Sixties Popular Culture

"Mother … is not quite herself today." (Re)constructions of Femininity in Sixties Popular Culture. “Incidentally, did you see that he’s now produced a virus that produces sterility in the male locust? – Admittedly the female locust can go on producing female locusts for a number of generations without male assistance, but one feels that it must tell sooner or later, or there wouldn’t be much sense in sex, would there…?” (Wyndham 1963: 22) §0. The aim of this paper is to see how the issue of femininit(ies) cross-stitches with that of representation in Sixties popular culture. For this reason I shall be looking at those narrative and cinematic texts which I consider representative of the Zeitgeist of the decade, focusing in particular on those which are most profoundly linked to the visual media – and as such to two period-related communication devices, television and colour filming. My attempt at making a cultural sense of the popular productions of the Sixties (and especially of B- genres such as spy thrillers, horror cinema and SF) is obviously profoundly indebted to a reading of the varying cultural, social, historical, political, and economic, scenario of the period, which finds two crucial - and juxtaposing - watersheds first in the post-war upsurge in conservatism and just a few years on in the post-68 revolutionary social trends, which developed as a consequence of (as well as a reaction to) the widespread change in mores triggered by World War II. As far as the issue of the representation of femininity is concerned, the decade presents at least two opposing, yet overlapping trends. -

Citation: Freeman, Sophie (2018) Adaptation to Survive: British Horror Cinema of the 1960S and 1970S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Citation: Freeman, Sophie (2018) Adaptation to Survive: British Horror Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/39778/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN PhD March 2018 ADAPTATION TO SURVIVE: BRITISH HORROR CINEMA OF THE 1960S AND 1970S SOPHIE FREEMAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences March 2018 Abstract The thesis focuses on British horror cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Rust Belt Blues a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University in Partial Fulfil

Rust Belt Blues A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Alison A. Stine June 2013 © 2013 Alison A. Stine. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Rust Belt Blues by ALISON A. STINE has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Dinty W. Moore Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT STINE, ALISON A., Ph.D., May 2013, English Rust Belt Blues Director of Dissertation: Dinty W. Moore Alison Stine’s Rust Belt Blues is a book-length work of linked creative nonfiction essays set in former manufacturing towns in Ohio, Indiana, and upstate New York. In pieces that range from autobiography to literary journalism, she focuses on abandoned places and people in the area known as the Rust Belt—a section of ex-industrial centers stretching from New York to Chicago—covering such topics as feral houses, graffiti, and the blues. She researches the Westinghouse factory that once employed a third of her hometown, explores a shuttered amusement park, re-visits a neglected asylum, and writes of rural poverty. In her critical introduction “The Abandoned Houses are All of Us: Toward a Rust Belt Persona,” Stine examines the work of contemporary nonfiction writers born in and / or concerned with the Rust Belt, finding that their work shares traits of deflection, obsession, lying, dark subject matter, and stubborn optimism—what she calls the defining characteristics of the emerging Rust Belt persona. -

This Is an Accepted Manuscript of an Article Published by The

After the Rural Idyll: Representations of the British Countryside as a Non-Idyllic Environment Tim Hall Department of Archaeology, Anthropology and Geography Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Winchester Sparkford Road Winchester Hampshire SO22 4NR tel: 01962 841515 fax: 01962 842280 [email protected] Main article Word count (main text): 4510 Key words: Rural, Representation, Non-idyllic, Modernity, National identity, Britain. This is an accepted manuscript of an article published by The Geographical Association in Geography, available online at https://www.geography.org.uk/Journal-Issue/f7103f6c-c33d-42ef- 8c89-899e356c18e2. It is not the copy of record. Copyright © 2020, Geographical Association. After the Rural Idyll: Representations of the British Countryside as a Non-Idyllic Environment Abstract This paper explores a somewhat overlooked tradition of non-idyllic representations of the British countryside, particularly characteristic of the post-World War Two period. It considers the collective significance of these representations and what they tell us of the place of the rural within contemporary British culture. The paper takes a broad survey approach, highlighting the representation of rural landscapes, rural communities and rural life, and the rural economy and rural labour, across a range of non-idyllic representations. It argues that it is no longer plausible to sustain the argument that the overwhelming imagination of British rural space is idyllic. These non-idyllic representations afford spaces to explore the imprints of modernity and globalisation on the British countryside, whilst the special place of the rural within British national identity now seems less secure. Introduction The rural, fondly idealised as bucolic, natural, unchanging, innocent and safe (Bell, 2006; Sommerville et al., 2015; Haigron, 2017), has long been posited as occupying a special place within British culture (Williams, 1973; Wiener, 1981; Colls and Dodd, 1986; Lowenthal, 1991; Short, 1992).