And Nineteenth-Century Rake Character to Depictions Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noel Carroll Source: the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol

The Nature of Horror Author(s): Noel Carroll Source: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Autumn, 1987), pp. 51-59 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/431308 Accessed: 12/05/2010 10:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The American Society for Aesthetics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. http://www.jstor.org NOEL CARROLL The Nature of Horror FOR NEARLY A DECADE and a half, perhaps espe- Romero's Night of the Living Dead or Scott's cially in America, horror has flourished as a Alien. -

Don Banks David Morgan Peter Racine Fricker Violin Concertos

SRCD.276 STEREO ADD Don Banks PETER RACINE FRICKER (1920-1990) David Morgan Concerto for Violin and small Orchestra Op. 11 (1950) (23’25”) 1 1st Movement: Con moto (9’42”) 2 2nd Movement: Andante (5’27”) Peter Racine Fricker 3 3rd Movement: Allegro vivo (8’16”) DAVID MORGAN (1933-1988) Violin Concerto (1966) * (26’02”) 4 1st Movement: Lento – Moderato cantabile – Alla Marcia (11’55”) 5 2nd Movement: Presto energico ma leggieramente (5’07”) Violin Concertos 6 3rd Movement: Lento – Allegro deciso – Con fuoco (9’00”) DON BANKS (1923-1980) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1968) (26’55”) 7 1st Movement: Lento – Allegro (9’42”) 8 2nd Movement: Andante cantabile (9’36”) 9 3rd Movement: Risoluto (7’37”) (76’26”) Yfrah Neaman, violin * Erich Gruenberg, violin Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Norman Del Mar * Vernon Handley The above individual timings will normally each include two pauses. One before the beginning of each movement or work, and one after the end. Erich Gruenberg • Yfrah Neaman ൿ 1974 * ൿ 1978 The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. This compilation and the digital remastering ൿ 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra © 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita Vernon Handley • Norman Del Mar by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK PETER RACINE FRICKER was born in Ealing on 5 September 1920. His middle name came from his great-grandmother, a direct descendant of the French dramatist. -

The Presence of the Jungian Archetype of Rebirth in Steven Erikson’S Gardens Of

The Presence of the Jungian Archetype of Rebirth in Steven Erikson’s Gardens of the Moon Emil Wallner ENGK01 Bachelor’s thesis in English Literature Spring semester 2014 Center for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Ellen Turner Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 The Collective Unconscious and the Archetype of Rebirth.................................................2 Renovatio (Renewal) – Kellanved and Dancer, and K’rul...................................................6 Resurrection – Rigga, Hairlock, Paran, and Tattersail.........................................................9 Metempsychosis – Tattersail and Silverfox.......................................................................15 The Presence of the Rebirth Archetype and Its Consequences..........................................17 Conclusion..........................................................................................................................22 Works Cited........................................................................................................................24 Introduction Rebirth is a phenomenon present in a number of religions and myths all around the world. The miraculous resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the perennial process of reincarnation in Hinduism, are just two examples of preternatural rebirths many people believe in today. However, rebirth does not need to be a paranormal process where someone -

(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” By

“(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” By Jennifer M. Abercrombie Foster @ Copyright 2016 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Yajaira Padilla ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Verónica Garibotto ________________________________ Jorge Pérez ________________________________ Vicky Unruh ________________________________ Hannah Britton ________________________________ Magalí Rabasa Date Defended: May 3, 2016 ii The Dissertation Committee for Jennifer M. Abercrombie Foster certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Yajaira Padilla ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Verónica Garibotto Date approved: May 9, 2016 iii Abstract Since the turn of the 20th century many writers, playwrights, and poets in Central America and the Hispanic Caribbean have published fantastic, gritty, and oftentimes unsettling stories of ghosts, anthropomorphic animals, zoomorphic humans, and uncanny spaces. These unexpected encounters and strange entities are an embodiment of muddled boundaries and -

Le Studio Hammer, Laboratoire De L'horreur Moderne

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 12 | 2016 Mapping gender. Old images ; new figures Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.8195 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference David Roche, “Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne ”, Miranda [Online], 12 | 2016, Online since 29 February 2016, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.8195 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne 1 Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche 1 This exciting conference1 was the first entirely devoted to the British exploitation film studio in France. Though the studio had existed since the mid-1940s (after a few productions in the mid-1930s), it gained notoriety in the mid-1950s with a series of readaptations of classic -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Gender Relations in Selected Restoration Comedies in the Mirror of Sociological Role Theory“ Verfasserin Johanna Holzer, Bakk. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ewald Mengel 2 to <3 3 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 2 Role Theory ............................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Introduction & Definition .................................................................................... 9 2.2 Role-play ........................................................................................................ 11 2.3 Self-monitoring ................................................................................................ 12 2.4 Inner Nature .................................................................................................... 14 2.4.1. Asides ........................................................................................................ 14 2.4.2. Body Language and Reactions .................................................................. 15 3 Restoration Comedy ............................................................................................ -

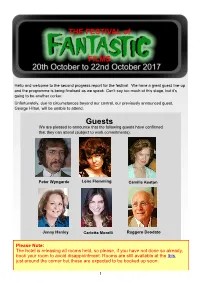

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend (Subject to Work Commitments)

Hello and welcome to the second progress report for the festival. We have a great guest line-up and the programme is being finalised as we speak. Can’t say too much at this stage, but it’s going to be another corker. Unfortunately, due to circumstances beyond our control, our previously announced guest, George Hilton, will be unable to attend. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend (subject to work commitments). Peter Wyngarde Lone Flemming Camille Keaton Jenny Hanley Carlotta Morelli Ruggero Deodato Please Note: The hotel is releasing all rooms held, so please, if you have not done so already, book your room to avoid disappointment. Rooms are still available at the Ibis, just around the corner but these are expected to be booked up soon. 1 Welcome to the Festival : Once again the Festival approaches and as always it is great looking forward to meeting old friends again and talking films. The main topic of conversation so far this year seems to be the imminent arrival of some more classic Hammer films on Blu Ray, at long last. Like so many of you, I am very much looking forward to these and it is fortuitous that this year Jenny Hanley is making a return visit to our festival, just as her Hammer magnum opus with Christopher Lee and Dennis Waterman, Scars of Dracula is on the list of new blu rays being released. I am having to face the inevitable question of how much longer I can go on, but that is not your problem. -

Le Studio Hammer, Laboratoire De L'horreur Moderne (10-12 Juin 2015)

Colloque : Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne (10-12 juin 2015) Comité organisateur : Gilles Menegaldo, Université de Poitiers, [email protected] ; Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris, Université Paris Ouest, [email protected], Université Paris 3, Mélanie Boissonneau, Université Paris 3/IRCAV, [email protected]. Lieux : Université Paris Ouest Nanterre (10 juin), Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle, Centre Censier, (11 juin), Cité Internationale, Fondation Lucien Paye (12 juin) Au moment de la réédition de la célèbre revue Midi-Minuit Fantastique (Rouge Profond) et dans une période où le genre fantastique/horrifique est particulièrement dynamique tant au cinéma que dans les séries télévisées, il semble opportun de faire retour sur le rôle joué par la Hammer Films, studio indépendant britannique qui, vingt ans après Universal, a fait revivre les grandes figures mythiques (Dracula, Frankenstein, la Momie, le Loup-garou etc.) en leur donnant une incarnation modernisée plus conforme à l’évolution de la société et des mœurs en Angleterre en particulier. Le studio Hammer est créé en 1934 par Enrique Carreras et William Hinds. Après des débuts assez modestes mais où déjà un style s’affirme, en particulier dans des films de SFcomme Le triangle à quatre côtés (1953), et The Quatermass Experiment (1955), le studio connaît un grand succès avec The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) suivi peu après parHorror of Dracula (1958), tous deux réalisés par Terence Fisher qui va imprimer sa marque, grâce aussi à des acteurs comme Christopher Lee et Peter Cushing, futures icônes du cinéma d’horreur. Le studio produit entre 1955 et 1979 près de 150 films et aussi deux séries télévisées à succès. -

University of California

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The English Novel's Cradle: The Theatre and the Women Novelists of the Long Eighteenth Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5q32j478 Author Howard, James Joseph Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The English Novel‘s Cradle: The Theatre and the Women Novelists of the Long Eighteenth Century A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by James Joseph Howard March 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. George E. Haggerty, Chairperson Dr. Carole Fabricant Dr. Deborah Willis Copyright by James Joseph Howard 2010 The Dissertation of James Howard is approved: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation for the guidance and encouragement provided during this project by my Dissertation Committee Chair, Dr. George Haggerty, and the positive support of the other committee members, Dr. Carole Fabricant and Dr. Deborah Willis. I would also like to thank Dr. John Ganim, who served on my doctoral examination committee, for his helpful insights before and especially during my oral examination, and Dr. John Briggs, for his initial encouragement of my entering the doctoral program at UC Riverside. I also extend my gratitude to all the English faculty with whom I had the pleasure of studying during my six years at the Riverside campus. Finally, I must make special mention of the English Graduate Staff Advisor, Tina Feldmann, for her unflinching dedication and patience in resolving not only my own interminable queries and needs, but also those of her entire ―family‖ of English graduate students. -

For More Than Seventy Years the Horror Film Has

WE BELONG DEAD FEARBOOK Covers by David Brooks Inside Back Cover ‘Bride of McNaughtonstein’ starring Eric McNaughton & Oxana Timanovskaya! by Woody Welch Published by Buzzy-Krotik Productions All artwork and articles are copyright their authors. Articles and artwork always welcome on horror fi lms from the silents to the 1970’s. Editor Eric McNaughton Design and Layout Steve Kirkham - Tree Frog Communication 01245 445377 Typeset by Oxana Timanovskaya Printed by Sussex Print Services, Seaford We Belong Dead 28 Rugby Road, Brighton. BN1 6EB. East Sussex. UK [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/#!/groups/106038226186628/ We are such stuff as dreams are made of. Contributors to the Fearbook: Darrell Buxton * Darren Allison * Daniel Auty * Gary Sherratt Neil Ogley * Garry McKenzie * Tim Greaves * Dan Gale * David Whitehead Andy Giblin * David Brooks * Gary Holmes * Neil Barrow Artwork by Dave Brooks * Woody Welch * Richard Williams Photos/Illustrations Courtesy of Steve Kirkham This issue is dedicated to all the wonderful artists and writers, past and present, that make We Belong Dead the fantastic magazine it now is. As I started to trawl through those back issues to chose the articles I soon realised that even with 120 pages there wasn’t going to be enough room to include everything. I have Welcome... tried to select an ecleectic mix of articles, some in depth, some short capsules; some serious, some silly. am delighted to welcome all you fans of the classic age of horror It was a hard decision as to what to include and inevitably some wonderful to this first ever We Belong Dead Fearbook! Since its return pieces had to be left out - Neil I from the dead in March 2013, after an absence of some Ogley’s look at the career 16 years, WBD has proved very popular with fans. -

The Country Wife by William Wycherley (1675) English Restoration Comedies- Stock Characters

English Restoration Comedies- Stock Characters The Country Wife by William Wycherley (1675) English Restoration Comedies- Stock Characters • The Rake - a fashionable or wealthy man of immoral or promiscuous habits. • The Cuckold- The character is the husband of a adulterous wife. • The fop- A foolish man overly concerned with his appearance and clothes in 17th century England. • The country father- A Father from the country • The coquette - A flirtatious woman. • The old crown - Old women who do nothing but gossip • The country daughter - the daughter of the Country father source: shivaniparkashenglishlit.weebly.com/the-country-wife-notes.html The Country Wife- Characters • Harry Horner: A notorious London rake who, in order to gain sexual access to “respectable” women, spreads the rumor that disease has rendered him impotent. Horner is the most insightful of all the “wits” in the play, often drawing out and commenting on the moral failings of others. • - Even though in announcing to the world that he is an impotent eunuch, Horner essentially emasculates himself and removes almost everything that makes him male, he is actually the most intelligent character in the play because he is the one who ends up ‘having it all’. • Mr. Pinchwife: Becomes a cuckold after pushing his naive wife away from him. He is a middle aged man newly married to the country wife Margery. A rake before his marriage, he is now the archetypal jealous husband: he lives in fear of being cuckolded, not because he loves his wife but because he believes that he owns her. He is a latent tyrant, potentially violent. -

Eoghain Hamilton

Edited by Eoghain Hamilton The Gothic - Probing the Boundaries Critical Issues Critical Issues Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Dr Daniel Riha Advisory Board Dr Alejandro Cervantes-Carson Dr Peter Mario Kreuter Professor Margaret Chatterjee Martin McGoldrick Dr Wayne Cristaudo Revd Stephen Morris Mira Crouch Professor John Parry Dr Phil Fitzsimmons Paul Reynolds Professor Asa Kasher Professor Peter Twohig Owen Kelly Professor S Ram Vemuri Revd Dr Kenneth Wilson, O.B.E A Critical Issues research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/critical-issues/ The Ethos Hub ‘The Gothic’ 2012 The Gothic - Probing the Boundaries Edited by Eoghain Hamilton Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-088-7 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2012. First Edition. Table