This Is an Accepted Manuscript of an Article Published by The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Our Last Catalog for 2018/19

1 MIDNIGHT MARQUEE 2018/19 CATALOG The Perfect GIFTS for Your Favorite Movie Buff! Vol. 1 NEW COVER WE KNOW MOVIES! Midnight Marquee Press • 9721 Britinay Lane, Baltimore, MD 21234 2 A Letter from Gary and Sue Svehla of Midnight Marquee Press We would like to apologize to our many long time customers as well as to our many new ones for the lateness of this catalog and our slowness in get- ting your orders out. It’s been a rough several years as Sue has been facing medical challenges, but we have finally found a diagnosis and she is on a healing path. Of course we will try to get your orders out quickly, but we’re getting old and slow (not to mention forgetful) so— if you need your books quickly, please order them from AMAZON.com or OLDIES.com. Most of our books are now being converted to e-books by Bear Manor Media, so you can order those from Amazon.com. We thank you for your patience, your business and your friendship through the years. Gary and Sue Svehla Table of Contents 3 New Titles from MMP Payment: We accept 5 Brit Horrors all major credit cards, 12 Italian Horror checks, money orders 15 Biographies and Autobios and PayPal. 19 Musical Bios 20 MidMar’s Actors Series Shipping: We try to 21 Histories of Horror Films ship within 7 work- ing days, but it’s just the two of us and we’re 25 Histories of Sci-Fi Films getting old and slow. 26 Hooray for Hollywood— other genres If you need your order fast, PLEASE 28 Exploitation Horrors order from Amazon.com or Oldies.com Most books will arrive from Createspace— 29 Forgotten Horrors & DVDs, mags, bookplates, etc. -

Noel Carroll Source: the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol

The Nature of Horror Author(s): Noel Carroll Source: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 46, No. 1 (Autumn, 1987), pp. 51-59 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The American Society for Aesthetics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/431308 Accessed: 12/05/2010 10:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The American Society for Aesthetics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. http://www.jstor.org NOEL CARROLL The Nature of Horror FOR NEARLY A DECADE and a half, perhaps espe- Romero's Night of the Living Dead or Scott's cially in America, horror has flourished as a Alien. -

Don Banks David Morgan Peter Racine Fricker Violin Concertos

SRCD.276 STEREO ADD Don Banks PETER RACINE FRICKER (1920-1990) David Morgan Concerto for Violin and small Orchestra Op. 11 (1950) (23’25”) 1 1st Movement: Con moto (9’42”) 2 2nd Movement: Andante (5’27”) Peter Racine Fricker 3 3rd Movement: Allegro vivo (8’16”) DAVID MORGAN (1933-1988) Violin Concerto (1966) * (26’02”) 4 1st Movement: Lento – Moderato cantabile – Alla Marcia (11’55”) 5 2nd Movement: Presto energico ma leggieramente (5’07”) Violin Concertos 6 3rd Movement: Lento – Allegro deciso – Con fuoco (9’00”) DON BANKS (1923-1980) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1968) (26’55”) 7 1st Movement: Lento – Allegro (9’42”) 8 2nd Movement: Andante cantabile (9’36”) 9 3rd Movement: Risoluto (7’37”) (76’26”) Yfrah Neaman, violin * Erich Gruenberg, violin Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Norman Del Mar * Vernon Handley The above individual timings will normally each include two pauses. One before the beginning of each movement or work, and one after the end. Erich Gruenberg • Yfrah Neaman ൿ 1974 * ൿ 1978 The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. This compilation and the digital remastering ൿ 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra © 2008 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita Vernon Handley • Norman Del Mar by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK PETER RACINE FRICKER was born in Ealing on 5 September 1920. His middle name came from his great-grandmother, a direct descendant of the French dramatist. -

PDF Download to the Devil, a Daughter Pdf Free Download

TO THE DEVIL, A DAUGHTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis Wheatley | 304 pages | 26 Aug 2014 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781448212620 | English | London, United Kingdom To the Devil, a Daughter PDF Book Utterly brilliant book; from start to finish, fast paced and monents of genuine horror, puts Hammer's film to shame as how they coukd make the film they did from brilliant material as Wheateley's excellent book i do not know!! Actually, she is not possessed by the Devil, as the quotation at the beginning of this review suggested, but her father became a Satanist and has signed away his soul and involved her in the initial rites, so that she is influenced by them. Widmark v Lee is a close one which I'm there for and it's a well paced, musically eerie, and bloody horror film. On the wish list. Enlarge cover. Add the first question. Wicking called the film "an awful mess. In the hours of darkness she becomes a Bad Girl, giving herself up to all kinds of naughtiness. Mar 11, Adele Geraghty rated it liked it. Black Magic 1 - 10 of 12 books. Details if other :. I DID enjoy Molly, but she ended up "disappearing" from the novel for a rather extended period of time, only to come back again at the end. Off it's head, completely mad and authored by someone with dodgy Right wing autocratic and aristocratic sympathies. About Dennis Wheatley. An amazing cast and some great atmosphere but just lacks something. Admittedly Molly takes part in the final assault on the enemy, though being a woman she of course slows them down. -

(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” By

“(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” By Jennifer M. Abercrombie Foster @ Copyright 2016 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Yajaira Padilla ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Verónica Garibotto ________________________________ Jorge Pérez ________________________________ Vicky Unruh ________________________________ Hannah Britton ________________________________ Magalí Rabasa Date Defended: May 3, 2016 ii The Dissertation Committee for Jennifer M. Abercrombie Foster certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “(Un)Natural Pairings: Fantastic, Uncanny, Monstrous, and Cyborgian Encounters in Contemporary Central American and Hispanic Caribbean Literature” ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Yajaira Padilla ________________________________ Co-Chairperson, Verónica Garibotto Date approved: May 9, 2016 iii Abstract Since the turn of the 20th century many writers, playwrights, and poets in Central America and the Hispanic Caribbean have published fantastic, gritty, and oftentimes unsettling stories of ghosts, anthropomorphic animals, zoomorphic humans, and uncanny spaces. These unexpected encounters and strange entities are an embodiment of muddled boundaries and -

Le Studio Hammer, Laboratoire De L'horreur Moderne

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 12 | 2016 Mapping gender. Old images ; new figures Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.8195 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference David Roche, “Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne ”, Miranda [Online], 12 | 2016, Online since 29 February 2016, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/8195 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.8195 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne 1 Conference Report: Le studio Hammer, laboratoire de l’horreur moderne Paris, (France), June 12-14, 2016 Conference organized by Mélanie Boissonneau, Gilles Menegaldo and Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris David Roche 1 This exciting conference1 was the first entirely devoted to the British exploitation film studio in France. Though the studio had existed since the mid-1940s (after a few productions in the mid-1930s), it gained notoriety in the mid-1950s with a series of readaptations of classic -

And Nineteenth-Century Rake Character to Depictions Of

TRACING THE ORIGINS OF THE EIGHTEENTH- AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY RAKE CHARACTER TO DEPICTIONS OF THE MODERN MONSTER COURTNEY A. CONRAD Bachelor of Arts in English Cleveland State University December 2011 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY MAY 2019 We hereby approve this thesis For COURTNEY A. CONRAD Candidate for the Master of Arts in English Literature degree for the Department of ENGLISH And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by ___________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Rachel Carnell __________________________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Member, Dr. Frederick Karem __________________________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Member, Dr. Gary Dyer __________________________________________ Department & Date Student’s Date of Defense: May 3, 2019 TRACING THE ORIGINS OF THE EIGHTEENTH- AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY RAKE CHARACTER TO DEPICTIONS OF THE MODERN MONSTER COURTNEY A. CONRAD ABSTRACT While critics and authors alike have deemed the eighteenth- and nineteenth- century literary rake figure as a “monster” and a “devil,” scholars have rarely drawn the same connections between monsters to rakes. Even as critics have decidedly characterized iconic monsters like Victor Frankenstein and Dracula as rapists or seducers, they oftentimes do not make the distinction -

From Decadent Diabolist to Roman Catholic Demonologist: Some Biographical Curiosities from Montague Summers’ Black Folio

From Decadent Diabolist to Roman Catholic Demonologist: Some Biographical Curiosities from Montague Summers’ Black Folio Bernard Doherty Introduction The history and practice of black magic, witchcraft, and Satanism have long held a deep fascination in British—and indeed international—popular culture. Beginning with the gothic literature of the eighteenth century, through to the nineteenth century occult revival and Victorian “penny dreadful,” and then into twentieth century pulp fiction, tales of the supernatural involving maleficent magic have been authored some of Britain’s most popular—if not always critically acclaimed—writers including, among others M. R. James, Arthur Machen, William Somerset Maugham, Agatha Christie, Charles Williams, and Dennis Wheatley. These writers, as well as various other short story writers, novelists, and journalists, have all played an important role in shaping, recording, and reflecting popular beliefs about these topics. Indeed, not a few occult practitioners, most notably Aleister Crowley, Dion Fortune, Gerald Gardner, and Doreen Valiente, even turned their hands to writing popular occult fiction. Despite this, the frequent blurring of the often porous boundary between actual occult practices and groups, and the imagined worlds of the purveyors of popular and literary fiction, has been seldom explored outside of highly specialised academic literature dedicated to the history of gothic or weird fiction and the burgeoning study of what has come to be called Western Esotericism.1 Bernard Doherty is a lecturer in the School of Theology at Charles Sturt University. 1 See, for example, Nick Freeman, ‘The Black Magic Bogeyman 1908–1935’, in The Occult Imagination in Britain, 1875–1947, ed. Christine Ferguson and Andrew Radford, pp. -

POST-BRITISH CRIME FILMS and the ETHICS of RETRIBUTIVE VIOLENCE Mark Schmitt (TU Dortmund University)

CINEMA 11 152 “THEY’RE BAD PEOPLE – THEY SHOULD SUFFER”: POST-BRITISH CRIME FILMS AND THE ETHICS OF RETRIBUTIVE VIOLENCE Mark Schmitt (TU Dortmund University) In recent years, British popular genre cinema has displayed a tendency to allegorise the ethical ques- tions resulting from the nation’s social and political challenges of the 21st century.1 Whether it is the Blair government’s decision to join the US in the Iraq war in 2003 and the ensuing disillusionment with democracy and the futility of public protest, the austerity measures and subsequently increasing social divisions in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008, the ongoing process of Scottish and Welsh devolution that challenges the very notion of a United Kingdom, Britain finds itself in a stage that Michael Gardiner has described as “post-British.”2 On the level of the nation-state, and especially with regard to Scottish and Welsh devolution, the post-British process can be identified as the “demo- cratic restructuring of each nation within union and each nation still affected by Anglophone imperial- ism”3, while the social structure of Britain is still marked by the internal fault lines of class divisions of class. The notion of “post-Britain” has been addressed in British film studies. William Brown has sug- gested that Britain’s cinematic output in the 21st century offers a “paradoxically post-British” perspec- tive which is reflected in subject matter, ideological points of view and modes of production.4 As Brown argues, such post-British perspectives can particularly be found in popular genre films such as 28 Days Later (2002) and V for Vendetta (2006).5 In the following, I will argue that this post-British sensibility in contemporary national genre cinema is aligned with urgent ethical questions regarding the nation state on both the British level as well as within a larger European context. -

1. Long Time Dead

1. LONG TIME DEAD In 2002, the filmmaker Richard Stanley sounded the death knell of ‘the great British horror movie’. His ‘obituary’, which appeared in Steve Chibnall and Julian Petley’s edited volume British Horror Cinema, lamented the general absence of any real directorial talent at the turn of the millennium, noting that the horror film directors ‘who really knew what they were doing escaped to Hollywood a long time ago’ (Stanley 2002: 194). Stanley cited the direct-to- video occult horror The 13th Sign (Jonty Acton and Adam Mason, 2000) as offering a glimmer of hope, but concluded that it was ‘still a long way below the minimum standard of even the most vilified 1980s product’ (2002: 193). Stanley’s pessimism was not unfounded (even if his assessment of The 13th Sign was perhaps a bit unfair). Hammer Films – the once-prolific film studio responsible for the first full-colour horror film, The Curse of Frankenstein (Terence Fisher), in 1957, and a host of other classic British horrors over the next two decades – buckled under market pressure and ceased making feature films in 1979. The 1980s, therefore, saw the production of only a handful of British horror films, which, at any rate, were mostly thought of as American productions that had peripheral British involvement, such as Stanley Kubrick’s blockbuster The Shining (1980) and Clive Barker’s franchise- initiating Hellraiser (1987). Others from the decade were artsy one-offs, such as the Gothic fairy tale The Company of Wolves (Neil Jordan, 1984), or (as was most often the case) amateurish flops, such as the cheap and clumsy monster movie Rawhead Rex (George Pavlou, 1986). -

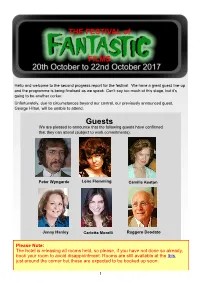

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend (Subject to Work Commitments)

Hello and welcome to the second progress report for the festival. We have a great guest line-up and the programme is being finalised as we speak. Can’t say too much at this stage, but it’s going to be another corker. Unfortunately, due to circumstances beyond our control, our previously announced guest, George Hilton, will be unable to attend. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend (subject to work commitments). Peter Wyngarde Lone Flemming Camille Keaton Jenny Hanley Carlotta Morelli Ruggero Deodato Please Note: The hotel is releasing all rooms held, so please, if you have not done so already, book your room to avoid disappointment. Rooms are still available at the Ibis, just around the corner but these are expected to be booked up soon. 1 Welcome to the Festival : Once again the Festival approaches and as always it is great looking forward to meeting old friends again and talking films. The main topic of conversation so far this year seems to be the imminent arrival of some more classic Hammer films on Blu Ray, at long last. Like so many of you, I am very much looking forward to these and it is fortuitous that this year Jenny Hanley is making a return visit to our festival, just as her Hammer magnum opus with Christopher Lee and Dennis Waterman, Scars of Dracula is on the list of new blu rays being released. I am having to face the inevitable question of how much longer I can go on, but that is not your problem. -

Unseen Horrors: the Unmade Films of Hammer

Unseen Horrors: The Unmade Films of Hammer Thesis submitted by Kieran Foster In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, March 2019 Abstract This doctoral thesis is an industrial study of Hammer Film Productions, focusing specifically on the period of 1955-2000, and foregrounding the company’s unmade projects as primary case studies throughout. It represents a significant academic intervention by being the first sustained industry study to primarily utilise unmade projects. The study uses these projects to examine the evolving production strategies of Hammer throughout this period, and to demonstrate the methodological benefits of utilising unmade case studies in production histories. Chapter 1 introduces the study, and sets out the scope, context and structure of the work. Chapter 2 reviews the relevant literature, considering unmade films relation to studies in adaptation, screenwriting, directing and producing, as well as existing works on Hammer Films. Chapter 3 begins the chronological study of Hammer, with the company attempting to capitalise on recent successes in the mid-1950s with three ambitious projects that ultimately failed to make it into production – Milton Subotsky’s Frankenstein, the would-be television series Tales of Frankenstein and Richard Matheson’s The Night Creatures. Chapter 4 examines Hammer’s attempt to revitalise one of its most reliable franchises – Dracula, in response to declining American interest in the company. Notably, with a project entitled Kali Devil Bride of Dracula. Chapter 5 examines the unmade project Nessie, and how it demonstrates Hammer’s shift in production strategy in the late 1970s, as it moved away from a reliance on American finance and towards a more internationalised, piece-meal approach to funding.