Shafter Report-V17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZANZEFF Shore to Store Project

Zero- and Near Zero-Emission Freight Facilities (ZANZEFF) Shore to Store Project In 2006, the Port of Los Angeles in partnership with the Port of Long Beach adopted the Clean Air Action Plan (CAAP), which was updated in 2010 and 2017 (https://cleanairactionplan.org). The CAAP identifies strategies to reduce air pollution from every source including ships, trucks, trains, harbor craft, and cargo handling equipment. Successful technology demonstrations of zero- and near zero-emission technologies may accelerate the availability of clean technologies that are necessary to implement existing strategies outlined in the CAAP or to develop future control measures, alternatives, or mitigation measures. Project Summary Project Partners The Port of Los Angeles in conjunction with the project ▪ California Air Resource Board (CARB) partners will demonstrate a collaborative zero- ▪ South Coast AQMD emission goods movement project. The project exhibits supply chain transport from “Shore to Store” utilizing ▪ Equilon Enterprises, LLC (d/b/a Shell Oil zero-emission advanced technology. The Shore to Store Products USA) project is funded with a $41,122,260 grant from the ▪ Kenworth International California Air Resources Board and an additional ▪ $41,426,612 in matching contributions from project Toyota Motor North America partners, including a Targeted Air Shed Grant for ▪ Port of Hueneme $1,000,000 from the South Coast AQMD. This project ▪ National Renewable Energy Laboratory was supported by the “California Climate Investments” ▪ Southern Counties Express -

Port Ships Are Massive L.A. Polluters. Will California Force A

Port ships are becoming L.A.’s biggest polluters. Will California force a cleanup? In December, a barge at the Port of Los Angeles uses a system, known as a bonnet or “sock on a stack,” that’s intended to scrub exhaust. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) Ships visiting Southern California’s bustling ports are poised to become the region’s larg est source of smogcausing pollutants in coming years, one reason state regulators want to reduce emissions from thousands more of them. Air quality officials want to expand the number of ships that, while docked, must either shut down their auxiliary engines and plug into shore power or scrub their exhaust by hooking up to machines known as bonnets or “socks on a stack.” But some neighbors of the ports say the California Air Resources Board is not moving fast enough to cut a rising source of pollution. Some also fear that the shipping industry and the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach will use their clout to weaken the proposed restrictions, which the Air Resources Board will decide on in the first half of the year. “We need relief; it’s just that simple,” said Theral Golden of the West Long Beach Assn., a neighborhood group that has long fought for cleaner air in a community that is among the hardest hit by port pollution. Ruben Garcia, president of Advanced Environmental Group, points out the telescoping tube of an emissions capture system that’s attached to a barge at the Port of L.A. (Allen J. -

Terms & Conditions

Terms & Conditions “SCS Video Contest 2020” contest (“Contest”) is organized by SCS Software s.r.o. with its registered office in Jihlavská 1558/21, Praha, 14000, Czech Republic, Identification Number 28181301, entered into Commercial Register maintained by Prague City Court, Section C, Insert No. 131111 (“Promoter”). The Contest Page is https://blog.scssoft.com/2020/01/scs-video-contest.html. The Contest is open to individuals aged eighteen (18) years or older, except employees, agents, contractors or consultants of the Promoter and their immediate families, the Promoter's associated companies and anyone else professionally connected with the Contest (“Entrants”). This Contest is void where prohibited by local law. The Contest is only open for players of a legal Steam copy of the game Euro Truck Simulator 2 or American Truck Simulator with an unlimited Steam account. Definition of the Limited Steam User Account is available on https://support.steampowered.com/kb_article.php?ref=3330-IAGK- 7663. There is no entry fee and no additional purchase is necessary to enter the Contest. To participate in the Contest each Entrant shall make a video capturing their play of either (i) Euro Truck Simulator 2 game, DLC Road to Black Sea or (ii) American Truck Simulator game, DLC Washington or Utah (“Video”); Euro Truck Simulator 2 and American Truck Simulator cannot be combined in one Video, Washington and Utah can be combined in one Video. Only one Video per Entrant will be included in the Contest, should an Entrant send more videos, only the one first received will be considered and any subsequent ones will be disregarded. -

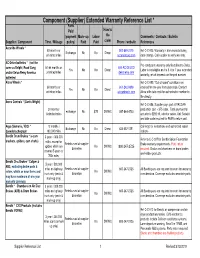

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List *

Component (Supplier) Extended Warranty Reference List * Parts Paid How to (payment Mark- up Labor file Comments / Contacts / Bulletin Supplier / Component Time / Mileage policy) Paid Paid claim Phone / website References Accuride Wheels * 60 months or 800-869-2275 Ref C-C-005. Warranty is from manufacturing Exchange No No Direct unlimited miles accuridecorp.com date (stamp). Call supplier to verify warranty. AC-Delco batteries * (not the Pro-rated parts warranty only filed direct to Delco. same as Delphi, Road Gang 60-84 months or 800-AC-DELCO Yes No No Direct Labor is not eligible on the 5, 6 or 7 year extended and/or Delco Remy America unlimited miles delcoremy.com warranty, which depends on the part number. batteries) Alcoa Wheels * Ref C-C-099. "Out of round" conditions are 60 months or 800-242-9898 covered for one year from date code. Contact Yes No No Direct unlimited miles alcoawheels.com Alcoa with date code for authorization number to file directly. Arens Controls * (Curtis Wright) Ref C-C-056. Supplier pays part at PACCAR 24 months/ production cost + $75 labor. Total payment for exchange No $75 DWWC 847-844-4703 Unlimited miles actuator is $292.19, selector varies. Unit Serial # and date code required for RMA to return part. Argo (Siemen's, VDO) * 12 months / Call Argo for instructions and authorized repair Exchange No No Direct 425-557-1391 Speedo/tachograph 100,000 miles stations. Bendix Drum Brakes * (s-cam 3 years / 300,000 Refer to C-C-007 for Bendix Spicer Foundation brackets, spiders, cam shafts) miles, except for Reimbursed at supplier Brake warranty requirements. -

Mariners Guide Port of Los Angeles 425 S

2019 MARINERS GUIDE PORT OF LOS ANGELES 425 S. Palos Verdes Street San Pedro, CA 90731 Phone/TDD: (310) 732-3508 portoflosangeles.org Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps fb.com/PortofLA @PortofLA @portofla The data contained herein is provided only for general informational purposes and no reliance should be placed upon it for determining the course of conduct by any user of the Port of Los Angeles. The accuracy of statistical data is not assured by this Port, as it has been furnished by outside agencies and sources. Acceptance of Port of Los Angeles Pilot Service is pursuant to all the terms, conditions and restrictions of the Port of Los Angeles Tariff and any amendments thereto. Mariners Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Welcome to the Port of Los Angeles and LA Waterfront . 2-3 Los Angeles Pilot Service . 4-5 Telephone Directory . 6-7 Facilities for Visiting Seafarers. .7 Safety Boating Safety Information. 10-11 Small (Recreational) Vessel Safety . 10-11 Mariners Guide For Emergency Calls . 11-12 Horizontal and Vertical Clearances . 12-13 Underkeel Clearance . 13-16 Controlled Navigation Areas. 16-17 Depth of Water Alongside Berths . 18 Pilot Ladder Requirements . 19-20 Inclement Weather Standards of Care for Vessel Movements 21-26 National Weather Service . 26 Wind Force Chart . 27 Tug Escort/Assist Information Tug Escort/Assistance for Tank Vessels . 30-31 Tanker Force Selection Matrix . .32 Tugs Employed in Los Angeles/Long Beach . 33 Tugs, Water Taxis, and Salvage. .34 Vessel Operating Procedures Radio Communications . 36 Vessel Operating Procedures . 37-38 Vessel Traffic Management . -

1 13 Hybrid Rubber- Tired Gantry (RTG) Cranes At

Table 2: Near-Term Action Plan (Years 2019-2023) (Revised Pursuant to Board Resolution No. 20-59, July 23, 2020) Appendix C Specific Implementing Summary of # Implementing Action Number Implementing Action Lead Action and Name 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Category Classification 1 13 Hybrid Rubber- E-CHE-3. The Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD) Tired Gantry (RTG) Expand Use of Hybrid awarded a Carl Moyer grant to Stevedoring Services of Cranes at SSAT Cargo-Handling America Terminals (SSAT), the terminal operator at the Equipment Where Oakland International Container Terminal (OICT), for Zero-Emissions the purchase of 13 hybrid RTG cranes. SSAT is using Equipment is Not T P this grant to replace the diesel engines in its entire fleet Commercially of RTG cranes at OICT. Phase-in is expected to require Available or approximately 2 years. The first RTG crane was repowered Operation Operation Operation Affordable in February 2019, and subsequent repowers are expected to occur approximately every 2 months. Overall criteria Implementation / Construction Implementation / Construction air pollutant emissions from the hybrid RTG cranes are reduced 99.5% compared to the existing diesel units. 2 90% Shore Power E-OGV-1. As part of its grant requirements, the Port will continue to Use Shore Power work with ocean carriers and tenants to improve plug-in Improvements - PO P rates to achieve an overall 90% plug-in rate in 2020. Achieve 90% Shore Impl./Constr. Power Use On-Going Activity On-Going Activity On-Going Activity On-Going Activity Zero- and Near-Zero-Emissions Freight Facilities (ZANZEFF) Project Components 3 10 Electric Class 8 E-T-4. -

Porting Schemes to Scale Missing

Vision on Hydrogen Valleys Mission Innovation “Hydrogen Valleys” w o r k s h o p 26 March 2019 Copyright of Shell International B.V. An inclusive group covering the whole value chain More major players should join the HydrogenCouncil in 2019 2 Copyright of Shell International B.V. STATUS OF HYDROGEN DEPLOYMENTS HYDROGEN SOURCES 4% To be fully decarbonised by 2050 Hydrocarbons 96% Electrolysis & by-products Source : IRENA, 3 data 2016 Copyright of Shell International B.V. KEY NEEDED STEPS FOR WIDER DEPLOYMENTS SHARED VISION BETWEEN KEY COUNTRIES ONGOING BLUE PRINT PROJECTS ONGOING CLEAR REGULATIONS SCATTERED SUPPORTING SCHEMES TO SCALE MISSING 4 Copyright of Shell International B.V. DRAFT DOCUMENT SCALE – EXEMPLE OF FLAGSHIP PROJECTS Projects pipeline of $90 billion 5 Copyright of Shell International B.V. DRAFT DOCUMENT HEAVY DUTY TRANSPORT an example of flagship project Shared Vision, Blue Print, Clear regulation, Supporting scheme Copyright of Shell International B.V. février 2019 6 DRAFT DOCUMENT Blue Print Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach The Port of Los Angeles and Port of Long Beach comprise the San Pedro Bay port complex, which handles more containers per ship call than any other port complex in the world. When combined, the two ports rank as the world's 9th busiest container port complex. San Pedro Bay Port Complex (Port of Los Angeles + Port of Long Beach) 190,000 jobs in Los Angeles/Long Beach (1 in 12) 992,000 jobs in five-county region (1 in 9) 2.8 million jobs throughout the U.S. 73% of west coast’s market share 32% of nation’s market share Copyright of Shell International B.V. -

T'fj ·Laifit .-Of:Thfn~Le~ -•Fqtllpt:\C&-- ·

., ..... ~\. ,. j NRL.Bc'ActtnmRiffl?DifedprlsSt1e$·,·__ s.f ry. Is:-- O.ff -to ' t'fJ ·laifit_.-of:tHfn~le~ -•fqtllpt:\C&-- ·. r'"··' -~ .. '· . 1 . - ·I ,, 01,~,: 1?~cembe:r: 2s: 1956 Roy G ;:-Hof~nia~n:, {i.cting re·gional ,, Somebo<ty QI1Ctf ~aid, ''the 9nl'y thing YOll 'ca.11 be sure of is change," and that 1'emark <i11Jr~eto~: of ~he 20th_ J:~gi~n ?f.tlrn ,:~at.i~.~al T.~b?r. Relati_ons J certainly applies, t& _the ,Calif. ~:Nev.-Utah Weather situation arid construction industry as \ve ~:oafd m -~an Fr~nqs~o; 1ss!1ed a comp}a.1nt ~gamst HensleJ' I i)1ov'e,. Jnto t0.g·new yea.1~ of 1957. · J&qmpment Co.; Inc. and: .Hensley Thietal ;I'rr.atin~ Co., Inc., an I If ,ve·_ sa;f it'i~ )lry- on·e of . the 1 --- ----- -"·--·-- ·- ·--·--·--- p!ffiliated company, lJpoii qharges· file<l' by Local No. 3. and at !· ~011gest ~iy st~ll,:/ on 1;eco1·d~th~n · _$ siune «fane ilismisse<l netitions fol' the electiofr fiH~l by} oy th0 tun~ '.'11s , go~s t9 pr?SS a!ltl ·. ·, : , ·. • : . • · ,· . · • · · , y ou get it,. tnere ·. ~v 11J 1i1·oha.bly be tllf:lSe tvvo q:nnpames. I . ' . ' . .' ~ I floo<ls'-everJ'.,:here. At : lill)''c rate The· complafot._ issu!),d aft1=r in- i !}aig·n,, aga!llS> that Company ~nd , that's how sh e . stands as of the ·e~ti.gat-ion. of -th e fads by tlie rep~···I ,mply '.n g ,that the u_mL.'U)l~ll lauor ; se_c;o nci t,;eei~ ,. -

Logistics M&A Industry Update

Issue: August 30, 2013 Logistics M&A Industry Update The McLean Group | www.mcleanllc.com | 703.827.0200 Industry Snapshot Five Weeks Ending Friday, August 30, 2013 Industry News . C.H. Robinson Worldwide appointed Ivo Aris director of global forwarding for C.H. Robinson Europe. Mr. Aris is charged with leading continental growth and advancement of the global forwarding division. Livingston International appointed Steven Preston CEO following Peter Luit’s retirement after 16 years at the helm. UTi Worldwide opened new London operations, expanding its existing air cargo hub. Complete with X-ray screening, bonded storage and refrigerated capabilities, the 33,000 square foot building serves as its primary UK air and road facility while consolidating air cargo to and from other UK locations. OnTrac will expand its San Diego overnight delivery service’s operation to 84,000 square feet to support increased volume. UPS Freight opened its new 72-door East Indianapolis Service Center on August 12. The new facility serves eastern Greater Indianapolis, complementing an existing 80-door Indianapolis Service Center that now serves the western metropolitan area. Expeditors International of Washington, Inc. reported Q2 2013 profits of $92.3 million, up 10.0% vs. Q2 2012’s $84.0 million. However, Q2 revenue slipped 0.3% year-over-year to $1.5 billion. C.H. Robinson Worldwide reported Q2 net income of $111.9 million, a 2.4% decline vs. Q2 2012’s $114.6 million. Q2 2013 revenue rose 11.3% to $3.3 billion, vs. $3.0 billion in Q2 2012. Notable M&A Activity Capital Markets (% Change) . -

USER MANUAL Welcome to American Truck Simulator

USER MANUAL Welcome to American Truck Simulator American Truck Simulator takes you on a journey through the breathtaking landscapes and widely recognized landmarks around the States. American Truck Simulator puts you in the seat of a driver for hire entering the local freight market, making you work your way up to become an owner-operator, and go on to create one of the largest transportation companies in the United States. Getting Started System requirements Minimum System Requirements: Operating system: Windows 7 64-bit Processor: Dual core CPU 2.4 GHz Memory: 4 GB RAM Graphics: GeForce GTS 450-class (Intel HD 4000) Storage: 3 GB available space Recommended System Requirements: Operating system: 7/8.1/10 64-bit Processor: Quad core CPU 3.0 GHz Memory: 6 GB RAM Graphics: GeForce GTX 760-class (2 GB) Storage: 3 GB available space Installation To install American Truck Simulator insert the game DVD into your DVD-ROM drive. Follow the on-screen instructions to complete the set-up process. If installation fails to start automatically, proceed by following these steps: 1. Open My Computer 2. Select and open your DVD-ROM drive 3. Find setup.exe and execute it 4. Follow the on-screen instructions to complete the set-up process Launching American Truck Simulator Start by clicking the “American Truck Simulator” icon on your desktop Creating a Profile To play American Truck Simulator you have to create a profile – a virtual person that will represent you in the game. Choose your name, gender, picture, preferred truck design, a logo and name for your company, confirm and start playing. -

Can Company 013230

PLEASE CONFIRM CSIP ELIGIBILITY ON THE DEALER SITE WITH THE "CSIP ELIGIBILITY COMPANIES" CAN COMPANY 013230 . Muller Inc 022147 110 Sand Campany 014916 1994 Steel Factory Corporation 005004 3 M Company 022447 3d Company Inc. 020170 4 Fun Limousine 021504 412 Motoring Llc 021417 4l Equipment Leasing Llc 022310 5 Star Auto Contruction Inc/Certified Collision Center 019764 5 Star Refrigeration & Ac, Inc. 021821 79411 Usa Inc. 022480 7-Eleven Inc. 024086 7g Distributing Llc 019408 908 Equipment (Dtf) 024335 A & B Business Equipment 022190 A & E Mechanical Inc. 010468 A & E Stores, Inc 018519 A & R Food Service 018553 A & Z Pharmaceutical Llc 005010 A A A - Corp. Only 022494 A A Electric Inc. 022751 A Action Plumbing Inc. 009218 A B C Contracting Co Inc 015111 A B C Parts Intl Inc. 018881 A Blair Enterprises Inc 019044 A Calarusso & Son Inc 020079 A Confidential Transportation, Inc. 022525 A D S Environmental Inc. 005049 A E P Industries 022983 A Folino Contruction Inc. 005054 A G F A Corporation 013841 A J Perri Inc 010814 A La Mode Inc 024394 A Life Style Services Inc. 023059 A Limousine Service Inc. 020129 A M Castle & Company 007372 A O N Corporation 007741 A O Smith Water Products 019513 A One Exterminators Inc 015788 A P S Security Inc 005207 A T & T Corp 022926 A Taste Of Excellence 015051 A Tech Concrete Co. 021962 A Total Plumbing Llc 012763 A V R Realty Company 023788 A Wainer Llc 016424 A&A Company/Shore Point 017173 A&A Limousines Inc 020687 A&A Maintenance Enterprise Inc 023422 A&H Nyc Limo / A&H American Limo 018432 A&M Supernova Pc 019403 A&M Transport ( Dtf) 016689 A. -

02-22-2017 Board Meeting Agenda

Orange County Sanitation District Wednesday, February 22, 2017 Regular Meeting of the 6:00 P.M. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Board Room 10844 Ellis Avenue Fountain Valley, CA 92708 (714) 593-7433 AGENDA CALL TO ORDER INVOCATION AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE (Denise Barnes, City of Anaheim) ROLL CALL (Clerk of the Board) 1. RECEIVE AND FILE MINUTE EXCERPTS OF MEMBER AGENCIES RELATING TO APPOINTMENTS TO THE ORANGE COUNTY SANITATION DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS (Clerk of the Board) CITY/AGENCY DIRECTOR ALTERNATE DIR. City of Fullerton Greg Sebourn Jesus Silva City of Santa Ana Sal Tinajero David Benavides City of Newport Beach Scott Peotter Brad Avery (amended) DECLARATION OF QUORUM (Clerk of the Board) PUBLIC COMMENTS: If you wish to address the Board of Directors on any item, please complete a Speaker’s Form (located at the table outside of the Board Room) and submit it to the Clerk of the Board or notify the Clerk of the Board the item number on which you wish to speak. Speakers will be recognized by the Chairperson and are requested to limit comments to three minutes. SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS: • Employee Service Award(s) • CSDA Transparency Certificate REPORTS: The Chair and the General Manager may present verbal reports on miscellaneous matters of general interest to the Directors. These reports are for information only and require no action by the Directors. 02/22/2017 OCSD Board of Directors’ Agenda Page 1 of 8 CONSENT CALENDAR: Consent Calendar Items are considered to be routine and will be enacted, by the Board of Directors, after one motion, without discussion.