The Journ Al of the Polynesian Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE JOURNAL of the POLYNESIAN SOCIETY VOLUME 127 No.2 JUNE 2018 the JOURNAL of the POLYNESIAN SOCIETY

THE JOURNAL OF THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY VOLUME 127 No.2 JUNE 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY Volume 127 JUNE 2018 Number 2 Editor MELINDA S. ALLEN Review Editor PHYLLIS HERDA Editorial Assistants MONA-LYNN COURTEAU DOROTHY BROWN Published quarterly by the Polynesian Society (Inc.), Auckland, New Zealand Cover image: Sehuri Tave adzing the exterior of a tamāvaka hull at Sialeva Point on the Polynesian Outlier of Takū. Photograph by Richard Moyle. Published in New Zealand by the Polynesian Society (Inc.) Copyright © 2018 by the Polynesian Society (Inc.) Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to: Hon. Secretary [email protected]. The Polynesian Society c/- Māori Studies University of Auckland Private Bag 92019, Auckland ISSN 0032-4000 (print) ISSN 2230-5955 (online) Indexed in SCOPUS, WEB OF SCIENCE, INFORMIT NEW ZEALAND COLLECTION, INDEX NEW ZEALAND, ANTHROPOLOGY PLUS, ACADEMIC SEARCH PREMIER, HISTORICAL ABSTRACTS, EBSCOhost, MLA INTERNATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY, JSTOR, CURRENT CONTENTS (Social & Behavioural Sciences). AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND Volume 127 JUNE 2018 Number 2 CONTENTS Notes and News ..................................................................................... 141 Articles RICHARD MOYLE Oral tradition and the Canoe on Takū .............................................. 145 CAMELLIA WEBB-GANNON, MICHAEL WEBB and GABRIEL SOLIS The “Black Pacific” and Decolonisation in Melanesia: Performing Négritude and Indigènitude .................................... 177 JOYCE D. HAMMOND Performing Cultural Heritage with Tīfaifai, Tahitian “Quilts” ........ 207 Reviews Coote, Jeremy (ed.): Cook-Voyage Collections of ‘Artificial Curiosities’ in Britain and Ireland, 1771–2015. IRA JACKNIS ...................................... -

Exploring 'The Rock': Material Culture from Niue Island in Te Papa's Pacific Cultures Collection; from Tuhinga 22, 2011

Tuhinga 22: 101–124 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2011) Exploring ‘the Rock’: Material culture from Niue Island in Te Papa’s Pacific Cultures collection Safua Akeli* and Shane Pasene** * Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ** Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: The Pacific Cultures collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) holds around 300 objects from the island of Niue, including textiles, costumes and accessories, weapons, canoes and items of fishing equipment. The history of the collection is described, including the increasing involvement of the Niue community since the 1980s, key items are highlighted, and collecting possibilities for the future are considered. KEYWORDS: Niue, material culture, collection history, collection development, community involvement, Te Papa. Introduction (2010). Here, we take the opportunity to document and publish some of the rich and untold stories resulting from the The Pacific Cultures collection of the Museum of New Niue collection survey, offering a new resource for researchers Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) comprises objects and the wider Pacific community. from island groups extending from Hawai‘i in the north to The Niue collection comprises 291 objects. The survey Aotearoa/New Zealand in the south, and from Rapanui in has revealed an interesting history of collecting and provided the east to Papua New Guinea in the west. The geographic insight into the range of objects that make up Niue’s material coverage is immense and, since the opening of the Colonial culture. -

Roger Curtis Green March 15, 1932–October 4, 2009

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ROGE R C U R T I S Gr EEN 1 9 3 2 — 2 0 0 9 A Biographical Memoir by PAT R I C K V . K I R CH Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2010 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. ROGER CURTIS GrEEN March 15, 1932–October 4, 2009 BY P ATRICK V . KIRCH OGER CURTIS GREEN, A TOWERING FIGURE in Pacific anthro- Rpology, passed away in his beloved home in Titirangi nestled in the hills overlooking Auckland on October 4, 2009, at the age of 77 years. Roger was one of the most influential archaeologists and historical anthropologists of Oceania in the second half of the 20th century. He revolutionized the field of Polynesian archaeology through his application of the settlement pattern approach. He conducted significant field research in New Zealand, French Polynesia, Samoa, Hawai‘i, the Solomon Islands, and the Bismarck Archipelago, advancing our knowledge of prehistory across the Pacific. His collaborations with historical linguists provided a firm foundation for the use of language reconstructions in prehis- tory, and he helped to advance a phylogenetic approach to historical anthropology. The Lapita Cultural Complex, now widely appreciated as representing the initial human settle- ment of Remote Oceania, was first largely defined through his efforts. And, he leaves an enduring legacy in the many students he mentored. EARLY YEARS Roger’s parents, Eleanor Richards (b. 1908) and Robert Jefferson Green (b. -

Polynesian Cultural Distributions Inj"Xew Perspective

816 A merican A nthropotogist [61, 1959] HALLOWELL, A. I. 1?.37 Cross-cousin marriage in the Lake Winnipeg area. In Twenty-fifth Anniversary studies, D. S. Davidson, ed. (Philadelphia Anthropological Society), I Philadelphia. ... 1949 The size of Algonkian hunting territories: A function of ecological adjustment. American Anthropologist 51 :35-45. Polynesian Cultural Distributions in J"Xew Perspective LANDES, RUTH 1937 Ojibwa sociology. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, XXIX. ANDREW PETER VAYDA LEAcoCK, ELEANOR Uni1Jersity of British Columbia 1955 Matrilocality in a simple hunting economy (Montagnais-Naskapi). Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 11:31-47. T HAS been an orthodox view in Oceanian anthropology that the pre-Eu SKINNER, A. I ropean Polynesians were capable of maintaining regular contacts between 1911 Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux. Anthropological Papers, islands separated by more than 300 miles of open ocean and that the peopling American Museum of Natural History, IX, 1. of Polynesia resulted either entirely orpredominantly from voyages of explora SPECK, F. G. 1915 Family hunting territories and social life of various Algonkian bands of the Ottawa tion and discovery followed by return voyages to the home islal'lds and then Valley. Memoirs of the Canada Department of Mines, Geological Survey, LXX. by deliberate large-scale migrations to newly discovered lands. These recon STEWARD, J- H. structions have been challenged by Andrew Sharp's impressively documented 1936 The economic and social basis of primitive bands. In Essays in Anthropology recent study (1956), which reviews the achievements and deficiencies of pre presented to A. L. Kroeber. Berkeley, University of California Press. -

Publications of the Polynesian Society

PUBLICATIONS OF THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY The publications listed below are available to members of the Polynesian Society (at a 20 percent discount, plus postage and packing), and to non-members (at the prices listed, plus postage and packing) from the Society’s office: Department of Mäori Studies, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92012, Auckland. All prices are in NZ$. Some Memoirs are also available from: The University Press of Hawai‘i, 2840 Kolowalu Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, U.S.A., who handle North American and other overseas sales to non-members. The prices given here do not apply to such sales. MÄORI TEXTS 1. NGATA, A.T. and Pei TE HURINUI, Ngä Möteatea: The Songs. Part One. Auckland: Auckland University Press and The Polynesian Society, 2004. xxxviii + 425 pp., CDs. Price $69.99 (cloth). 2. NGATA, A.T. and Pei TE HURINUI, Ngä Möteatea: The Songs. PartTwo. Auckland: Auckland University Press and The Polynesian Society, 2005. li + 464 pp., CDs. Price $69.99 (cloth). 3. NGATA, A.T. and Pei TE HURINUI, Ngä (MöteateaPart 3). Facsimile of 1970 edition, xxiii, 457pp. 1980. (out-of-print, new edition forthcoming 2006). 4. NGATA, A.T., Ngä Möteatea (Part 4). x, 150pp. 1990. Price $30.00 paper. MEMOIR SERIES 14. OLDMAN, W.O., The Oldman Collection of Maori Artifacts. New Edition with introductory essay by Roger Neich and Janet Davidson, and finder list. 192pp., including 104 plates. 2004. Price $30. 15. OLDMAN, W.O., The Oldman Collection of Polynesian Artifacts. New Edition with introductory essay by Roger Neich and Janet Davidson, and finder list. -

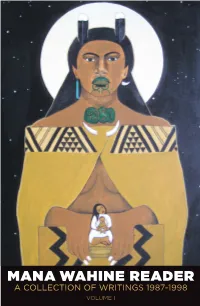

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

A Critical Examination of Film Archiving and Curatorial Practices in Aotearoa New Zealand Through the Life and Work of Jonathan Dennis

Emma Jean Kelly A critical examination of film archiving and curatorial practices in Aotearoa New Zealand through the life and work of Jonathan Dennis 2014 Communications School, Faculty of Design and Creative Technology Supervisors: Dr Lorna Piatti‐Farnell (AUT), Dr Sue Abel (University of Auckland) A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 1 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements:...................................................................................................................................... 6 Glossary of terms: ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Archival sources and key: ............................................................................................................................ 10 Interviews: .............................................................................................................................................. 10 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 11 2. Literature Review ................................................................................................................................... -

THE JOURNAL of the POLYNESIAN SOCIETY VOLUME 112 No.4 DECEMBER 2003 Coverdec03.Qxd 22/01/2004 7:39 A.M

coverdec03.qxd 22/01/2004 7:39 a.m. Page 1 THE JOURNAL OF THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY THE POLYNESIAN OF THE JOURNAL The Journal of the Polynesian Society VOLUME 112 No.4 DECEMBER 2003 VOLUME VOLUME 112 No.4 DECEMBER 2003 THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND NEW ZEALAND THE JOURNAL OF THE POLYNESIAN SOCIETY Volume 112 DECEMBER 2003 Number 4 Editor JUDITH HUNTSMAN Review Editor MARK BUSSE Editorial Assistants CLAUDIA GROSS DOROTHY BROWN Published quarterly by the Polynesian Society (Inc.), Auckland, New Zealand Published in New Zealand by the Polynesian Society (Inc.) Copyright © 2003 by the Polynesian Society (Inc.) Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to: Hon. Secretary The Polynesian Society c/- Mäori Studies The University of Auckland Private Bag 92019, Auckland ISSN 0032-4000 Indexed in CURRENT CONTENTS, Behavioural, Social and Managerial Sciences, in INDEX TO NEW ZEALAND PERIODICALS, and in ANTHROPOLOGICAL INDEX. AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND Volume 112 DECEMBER 2003 Number 4 CONTENTS Notes and News ......................................................................................329 Articles ROGER NEICH The Mäori House Down in the Garden: A Benign Colonialist Response to Mäori Art and the Mäori Counter-response .............. 331 ANGELA TERRILL Linguistic Stratigraphy in the Central Solomon Islands: Lexical Evidence of Early Papuan/Austronesian Interaction ..................... 369 Reviews Blench, Roger and Matthew Spriggs (eds): Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts, Languages, and Texts. MICHAEL W. GRAVES ....................... 403 Clark, G.R., A.J. Anderson and T. -

Testing Migration Patterns and Estimating Founding Population Size

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 9047–9052, July 1998 Anthropology, Evolution Testing migration patterns and estimating founding population size in Polynesia by using human mtDNA sequences (hypervariable region Iyhuman evolutionyNew Zealand Maoriysensitivity analysis) ROSALIND P. MURRAY-MCINTOSH*†,BRIAN J. SCRIMSHAW‡,PETER J. HATFIELD§, AND DAVID PENNY* *Institute for Molecular BioSciences, Massey University, P.O. Box 11222, Palmerston North, New Zealand; ‡Institute of Environmental Science and Research, Wellington, New Zealand; and §Renal Unit, Wellington Hospital, Wellington, New Zealand Communicated by Patrick V. Kirch, University of California at Berkeley, Stanford, CA, March 30, 1998 (received for review July 10, 1997) ABSTRACT The hypervariable 1 region of human mtDNA Pre-Polynesians are thought to have occupied the eastern islands shows markedly reduced variability in Polynesians, and this of South-East Asia at '2,000 BC, their Lapita culture with its variability decreases from western to eastern Polynesia. Fifty- characteristic pottery expanding rapidly through Melanesia and four sequences from New Zealand Maori show that the mito- out from the Solomon Islands into the western islands of Polyne- chondrial variability with just four haplotypes is the lowest of any sia (such as Tonga and Samoa) by '1,200–1,000 BC (19, 20). sizeable human group studied and that the frequency of haplo- Expansion to the eastern islands of the Pacific occurred largely types is markedly skewed. The Maori sequences, combined with between AD 1 and 1,000 (20, 21). Eastern Polynesia includes 268 published sequences from the Pacific, are consistent with a Tahiti (Society Islands), Easter Island, Hawaii, Marquesas, series of founder effects from small populations settling new Northern and Southern Cooks, the Australs, Pitcairn, and New island groups. -

Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1952 Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times John L. Sorenson Sr. Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sorenson, John L. Sr., "Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times" (1952). Theses and Dissertations. 5131. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5131 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. e13 ci j rc171 EVIDENCES OPOFCULTURE CONTACTS BETWEEN POLIIESIAPOLYNESIA AND tiletlleTIIETHE AMERICAS IN preccluivibianPREC olto4bian TIMES A thesthesisis presented tobo the department of archaeology brbrighamighambigham Yyoungoung universityunivervens 1 ty provo utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts n v rb hajbaj&aj by john leon sorenson july 1921952 ACmtodledgiventsackiiowledgments thanks are proffered to dr M wells jakenjakemjakemanan and dr sidney B sperry for helpful corencoxencommentsts and suggestions which aided research for this thesis to the authors wife kathryn richards sorenson goes gratitude for patient forbearance constant encouragement -

Australia and the Secretive Exploitation of the Chatham Islands to 1842

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2017 Australia and the Secretive Exploitation of the Chatham Islands to 1842 Andre Brett University of Melbourne, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brett, Andre, "Australia and the Secretive Exploitation of the Chatham Islands to 1842" (2017). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 3555. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/3555 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Australia and the Secretive Exploitation of the Chatham Islands to 1842 Abstract The European discovery of the Chatham Islands in 1791 resulted in significant consequences for its indigenous Moriori people. The colonial Australian influence on the Chathams has eceivr ed little scholarly attention. This article argues that the young colonies of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land led the exploitation of the archipelago before its annexation to New Zealand in 1842. The Chathams became a secretive outpost of the colonial economy, especially the sealing trade. Colonial careering transformed the islands: environmental destruction accompanied economic exploitation, with deleterious results for the Moriori. When two Māori iwi (tribes) from New Zealand's North Island invaded in 1835, Moriori struggled to respond as a consequence of the colonial encounter. Mobility and technology gained from the Australian colonies enabled and influenced the invasion itself, and derogatory colonial stereotypes about Aboriginal peoples informed the genocide that ensued. -

Polynesian Origins and Destinations: Reading the Pacific with S Percy Smith

Polynesian Origins and Destinations: Reading the Pacific with S Percy Smith Graeme Whimp A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University May 2014 ii This thesis is the original work of the author unless otherwise acknowledged. Graeme Whimp Department of Pacific and Asian History School of Culture, History and Language ANU College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University iii iv Abstract ______________________________________________________________________ Stephenson Percy Smith, militia member, surveyor, ethnologist and ethnographer, and founder of the Polynesian Society and its Journal, had a major impact on the New Zealand of his day and on a world-wide community of Polynesianist scholars. Whereas a good deal of attention and critique has been given to his work on Māori and the settlement of New Zealand, the purpose of this thesis is to explore those of his writings substantially devoted to the island Pacific outside New Zealand. To that end, I assemble a single Text comprising all of those writings and proceed to read it in terms of itself but also in the light of the period in which it was written and of its intellectual context. My method, largely based on elements of the approach proposed by Roland Barthes in the early 1970s, involves first presenting a representation of that Text and then reading within it a historical figure, the author of its components, as a character in that Text. Before doing so, in a Prologue I set out the broad current understanding of the patterns of settlement of the Pacific and some of the origins of Smith’s racial framing.