World War in the Wasatch Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrea Abbate Annie Abbott Rose Abdoo Louisa

CHARACTERS and COMEDIENNES ACADEMY PLAYERS DIRECTORY #196 BOOK PAGE: 1 Agency(310)Personal 273-0744(213)Jo for Anne theN11571500 466-5170ManagementInc.96 Performing Astrow (212) 582- Arts, RussianImprovisation,SusanMid-EastGerman5Accent,DANCETerryCOUNSELLOR-AT-LAW,THESEVENTHMAD ft.Accent,LEGALINTOCommercialAccent,FEATURED 3(818)(213)ROSEANNE Accent,NatheYOUNG LichtmanRESTLESSSpecial in.LA ABOUT Accent,New THEWITHAccent,M8530CreditsER EAGLESC.P.C. FrenchLAW 120783-3003653-7573Irish91 HEAVEN & Singer, WOODS,TVYork Italian Skills Associates/AND MEAgency YOUlbs.Company StageAccent, TV Southern- TVMidwest- Accent TV Accent, Film Stage THEBritish-AdultAccent, TV (213)NewFencing,Accent, 878-1155YorkGeddesSpecial Firearms, SpanishL9984Accent,833396 Agency Skills (312) Russian- Accent Singer, 787- 5C.L.Inc.Personal ft.CHICAGOCommercialGABRIEL'S 4(213)SEINFELDSpecial in.HenryCreditsH6173Singer Talent 200461-3971461-5699Management96 HOPE Ong SkillsFIRE Agencylbs. Agency TV TV AdultTV ANDREA ANNIE ROSE LOUISA ABBATE ABBOTT ABDOO ABERNATHY MOTHERBritishTHOMPSONSAccent,Ice(714) Skating,ONEFEATUREDSpecial Accent,Messages & SouthernM6668Credits INCHCHILD, 751-500796 Swimming, Skills New EXPRESS, FilmDIE, STAR Accent York- TV 5 ft.Cavaleri 8(818) in.L8722 122Adult 955-9300&96 Associates lbs. Mature (310)Cycling,5Sailing, ft.Commercial 274-93565GillaSpecial in.Swimming Equestrian,N0179 Scuba7820 Roos,13596 Skills Agencylbs. (212) Diving,Ltd. Guitar, Adult 727- IT'SMURDER,TALES APersonal MAD,(818)HenriWORLD OFM2916Credits SHE MAD, 784-0534Management96 BollingerTHE -

Not So Quirky: on Subject Case in Ice- Landic1

5 Not so Quirky: On Subject Case in Ice- landic 1 JÓHANNES GÍSLI JÓNSSON 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of subject case in Icelandic, extending and refining the observations of Jónsson (1997-1998) and some earlier work on this topic. It will be argued that subject case in Icelandic is more predictable from lexical semantics than previous studies have indicated (see also Mohanan 1994 and Narasimhan 1998 for a similar conclusion about Hindi). This is in line with the work of Jónsson (2000) and Maling (2002) who discuss various semantic generalizations about case as- signment to objects in Icelandic. This paper makes two major claims. First, there are semantic restrictions on non-nominative subjects in Icelandic which go far beyond the well- known observation that such subjects cannot be agents. It will be argued that non-nominative case is unavailable to all kinds of subjects that could be described as agent-like, including subjects of certain psych-verbs and intransitive verbs of motion and change of state. 1 I would like to thank audiences in Marburg, Leeds, York and Reykjavík and three anony- mous reviewers for useful comments. This study was supported by grants from the Icelandic Science Fund (Vísindasjóður) and the University of Iceland Research Fund (Rannsóknasjóður HÍ). New Perspectives in Case Theory. Ellen Brandner and Heike Zinsmeister (eds.). Copyright © 2003, CSLI Publications. 129 130 / JOHANNES GISLI JONSSON Second, the traditional dichotomy between structural and lexical case is insufficient in that two types of lexical case must be recognized: truly idio- syncratic case and what we might call semantic case. -

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work PROFESSIONAL TRACK 2009-present Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 2003-2009 Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1997-2003 Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1994-99 Faculty, Department of Ancient Scripture, BYU Salt Lake Center 1980-97 Department Chair of Home Economics, Jordan School District, Midvale Middle School, Sandy, Utah EDUCATION 1997 Ed.D. Brigham Young University, Educational Leadership, Minor: Church History and Doctrine 1992 M.Ed. Utah State University, Secondary Education, Emphasis: American History 1980 B.S. Brigham Young University, Home Economics Education HONORS 2012 The Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award: Presented in recognition of an outstanding published scholarly article or academic book in Church history, doctrine or related areas for Against the Odds: The Life of George Albert Smith (Covenant Communications, Inc., 2011). 2012 Alice Louise Reynolds Women-in-Scholarship Lecture 2006 Brigham Young University Faculty Women’s Association Teaching Award 2005 Utah State Historical Society’s Best Article Award “Non Utah Historical Quarterly,” for “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899-1922.” 1998 Kappa Omicron Nu, Alpha Tau Chapter Award of Excellence for research on David O. McKay 1997 The Crystal Communicator Award of Excellence (An International Competition honoring excellence in print media, 2,900 entries in 1997. Two hundred recipients awarded.) Research consultant for David O. McKay: Prophet and Educator Video 1994 Midvale Middle School Applied Science Teacher of the Year 1987 Jordan School District Vocational Teacher of the Year PUBLICATIONS Authored Books (18) Casey Griffiths and Mary Jane Woodger, 50 Relics of the Restoration (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Press, 2020). -

The State of Mormon Literature and Criticism

The State of Mormon Literature and Criticism Gideon Burton and Neal Kramer Gideon Burton and Neal Kramer both serve on the board of the Association for Mormon Letters. In consultation with Dialogue's editors, they have chosen and edited the selections for this issue. Two DECADES HAVE PASSED SINCE Dialogue last published an issue entirely devoted to Mormon literature. In the meantime literary writing about Latter-day Saints has been burgeoning both in LDS and national mar- kets—so much so that it is difficult for literary critics to keep up with this growing body of novels, plays, poetry, and literary nonfiction. It is very important, however, that they try. To have a sense of the future of Mor- mon literature, it is vital that we see how present writings articulate with traditions from the past. Producing literary criticism to do just that is the central function of the Association for Mormon Letters, whose goal is to serve authors, scholars, and general readers of Mormon literature. In our yearly confer- ence, through readings, book reviews, a very active e-mail list, and now an annual writers' workshop and a small quarterly literary magazine, Ir- reantum, we attempt to introduce people to Mormon literature past and present and to critically evaluate it. In this issue of Dialogue, we share with a broader public some of the best criticism that has been generated at our conferences and published in the annuals of the Association, as well as a sampling of new creative works from active writers. As editors we have found our task different from the one faced by editors of Dialogue's prior literary issues because the object of our study has been evolving, as have our means of literary analysis. -

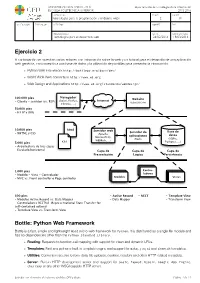

Ejercicio 2 Bottle: Python Web Framework

UNIVERSIDAD SAN PABLO - CEU departamento de tecnologías de la información ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA SUPERIOR 2015-2016 ASIGNATURA CURSO GRUPO tecnologías para la programación y el diseño web i 2 01 CALIFICACION EVALUACION APELLIDOS NOMBRE DNI OBSERVACIONES FECHA FECHA ENTREGA Tecnologías para el desarrollo web 24/02/2016 18/03/2016 Ejercicio 2 A continuación se muestran varios enlaces con información sobre la web y un tutorial para el desarrollo de una aplicación web genérica, con conexión a una base de datos y la utilización de plantillas para presentar la información. ‣ Python Web Framework http://bottlepy.org/docs/dev/ ‣ World Wide Web consortium http://www.w3.org ‣ Web Design and Applications http://www.w3.org/standards/webdesign/ Navegador 100.000 pies Website (Safari, Firefox, Internet - Cliente - servidor (vs. P2P) uspceu.com Chrome, ...) 50.000 pies - HTTP y URIs 10.000 pies html Servidor web Servidor de Base de - XHTML y CSS (Apache, aplicaciones datos Microsoft IIS, (Rack) (SQlite, WEBRick, ...) 5.000 pies css Postgres, ...) - Arquitectura de tres capas - Escalado horizontal Capa de Capa de Capa de Presentación Lógica Persistencia 1.000 pies Contro- - Modelo - Vista - Controlador ladores - MVC vs. Front controller o Page controller Modelos Vistas 500 pies - Active Record - REST - Template View - Modelos Active Record vs. Data Mapper - Data Mapper - Transform View - Controladores RESTful (Representational State Transfer for self-contained actions) - Template View vs. Transform View Bottle: Python Web Framework Bottle is a fast, simple and lightweight WSGI micro web-framework for Python. It is distributed as a single file module and has no dependencies other than the Python Standard Library. -

WEB2PY Enterprise Web Framework (2Nd Edition)

WEB2PY Enterprise Web Framework / 2nd Ed. Massimo Di Pierro Copyright ©2009 by Massimo Di Pierro. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Copyright owner for permission should be addressed to: Massimo Di Pierro School of Computing DePaul University 243 S Wabash Ave Chicago, IL 60604 (USA) Email: [email protected] Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created ore extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: WEB2PY: Enterprise Web Framework Printed in the United States of America. -

A Guide to Brazil's Oil and Oil Derivatives Compliance Requirements

A Guide to Brazil’s Oil and Oil Derivatives Compliance Requirements A Guide to Importing Petroleum Products (Oil and Oil Derivatives) into Brazil 1. Scope 2. General View of the Brazilian Regulatory Framework 3. Regulatory Authorities for Petroleum Products 3.1 ANP’s Technical Regulations 3.2 INMETRO’s Technical Regulations 4. Standards Developing Organizations 4.1 Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT) 5. Certifications and Testing Bodies 5.1 Certification Laboratories Listed by Inmetro 5.2 Testing Laboratories Listed by Inmetro 6. Government Partners 7. Major Market Entities 1 A Guide to Importing Petroleum Products (Oil and Oil Derivatives) into Brazil 1. Scope This guide addresses all types of petroleum products regulated in Brazil. 2. General Overview of the Brazilian Regulatory Framework Several agencies at the federal level have the authority to issue technical regulations in the particular areas of their competence. Technical regulations are always published in the Official Gazette and are generally based on international standards. All agencies follow similar general procedures to issue technical regulations. They can start the preparation of a technical regulation ex officio or at the request of a third party. If the competent authority deems it necessary, a draft regulation is prepared and published in the Official Gazette, after carrying out an impact assessment of the new technical regulation. Technical regulations take the form of laws, decrees or resolutions. Brazil normally allows a six-month period between the publication of a measure and its entry into force. Public hearings are also a way of promoting the public consultation of the technical regulations. -

For Fuel 1 (BDN) at 550, 1,100 and 1,650 Bar Injection Pressures

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Fatmi, Zeeshan (2018). Optical and chemical characterisation of the effects of high-pressure hydrodynamic cavitation on diesel fuel. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/22683/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] OPTICAL AND CHEMICAL CHARACTERISATION OF THE EFFECTS OF HIGH-PRESSURE HYDRODYNAMIC CAVITATION ON DIESEL FUEL Zeeshan Fatmi This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Mathematics, Computer Science and Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering February 2018 i Table of Contents 2.1 Diesel Fuel................................................................................................................... 7 2.1.1 Distillation from Crude Oil and Conversion Processes ....................................... 7 2.1.2 Diesel Fuel Components .................................................................................... 10 2.1.3 Diesel Fuel Properties and Performance Parameters ........................................ -

Articles and More Are Available at Maxwellinstitute.Byu.Edu

“The Testimony of Men” William E. McLellin and the Book of Mormon Witnesses Mitchell K. Schaefer recently discovered circa 1871 manuscript written by William A McLellin, an early Mormon Apostle and, later, apostate, includes a passage that narrates how, in 1833, he engaged two of the three and one of the eight witnesses of the Book of Mormon about the nature of their experiences as witnesses. The testimonies of the witnesses printed in each copy of the Book of Mormon are some of the most compelling evidence in favor of its miraculous revelation and translation. For believers, this evidence approaches proof of Joseph Smith’s miraculous claims. But some have questioned the nature of the testimonies and made a strong coun- terargument that what the witnesses experienced was solely supernatural and not, therefore, credible. The witnesses, this argument asserts, only experienced the plates via an unverifiable subjective experience, rendering their statements void. Historians have generally adopted one of two interpretations of the historical record by and about the Book of Mormon witnesses. Historians who believe the statements of the witnesses as credible usually focus fore- most on the original testimonies published in the Book of Mormon and on the witnesses’ fidelity to their statements despite dissent and disaffection by many of them from the Church itself. The leading historian espousing this interpretation of the evidence is Richard Lloyd Anderson. In his work Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses, Anderson holds that despite the fact that the witnesses left the Church at one point or another, they never denied their testimonies of the events that solidified their belief in BYU Studies 50, no. -

Im Frauenlager Von Auschwitz-Birkenau Stellte Die Lagerleiterin Maria Mandl Im Oktober 1942 Auf Inoffiziellem Wege Ein „Mädch

1 DAS ORCHESTER VON BLOCK 12 EINLEITUNG Im Frauenlager von Auschwitz-Birkenau stellte die Lagerleiterin Maria Mandl im Oktober 1942 auf inoffiziellem Wege ein „Mädchenorchester“ zusammen, das zwischen 1943 und 1944 unter der Leitung der Geigerin Alma Rosé stand. Die Musikerinnen lebten und probten in einer separaten Baracke, dem Block 12 (später im Block 7). Mitglieder der Lagerkapelle von Kaunas (Kauen). Das 1942 gegründete Orchester bestand aus 35 Musikern und fünf Sängern und gab im Ghetto etwa 80 Konzerte. Diese fanden in der dortigen Polizeistation statt. Im selben Gebäude hatte vor der deutschen Besatzung eine Jeschiwa ihren Platz. Die funktionale Rolle der Nazi-Lager beim Völkermord an den Juden, wie auch an den Sinti und Roma, gibt dem Phänomen der Musik an diesen Orten eine besondere Bedeutung. Dadurch, dass sie – teilweise – die organisierte Vernichtung ganzer Völker „untermalte“, kommt ihr in diesem Kontext eine Symbolik zu, die noch bestärkt wird durch die Bedeutung, die die Nazis ihr zu Propagandazwecken im Ghettolager Theresienstadt zumaßen. Die verschiedene Musik, die Alma Rosé (1906-1944): Erfolgreiche Geigerin (1); an der Spitze ihres sowohl in den Vernichtungs- wie auch in den übrigen Orchesters, der „Wiener Walzermädeln“ in den 30er Jahren (2); als Dirigentin des Mädchenorchesters von Auschwitz-Birkenau. Die Kapelle begleitet die Rückkehr Konzentrationslagern erklang, war aber nicht ausschließlich eines Arbeitskommandos. Zeichnung von Mieczyslaw Koscielniak (3). mit dem Genozid an den europäischen Juden verbunden. Diese Ausstellung erklärt, welche Rolle die Musik in den deutschen Dass es in den Nazi-Lagern Musik gegeben hat und diese sogar KZs spielte und in welchen Formen sie auftrat. einen besonderen Stellen-wert hatte, ist heute weitgehend bekannt, wurde jedoch erst in den 1980er-Jahren von Musikalische Aktivitäten gab es im Übrigen nicht nur Expertenseite bestätigt – so schien die Kunst doch völlig in den nationalsozialistischen Lagern, sondern in den unvereinbar mit dem Kontext, in dem sie entstand. -

Gender and Literature

english edition 2 2017 Gender and Literature issue editor ANNA NASIŁOWSKA SŁAWOMIR BURYŁA Manly Fascism AGNIESZKA DAUKSZA KwieKulik as an Unknown: A Neo-Avant-gardist Laboratory of Experience ARÁNZAZU CALDERÓN PUERTA The Theme of Rape in Ida Fink’s Aryan Papers and Tadeusz Słobodzianek’s Our Class KRYSTYNA KŁOSIŃSKA The Secret of the Dulskis’ Establishment WOJCIECH ŚMIEJA A Piece of Fedora Cake: The Male-Centric Imagination of Jerzy Andrzejewski and the Scholarly Reconnaissance MONIKA ŚWIERKOSZ Arachne and Athena: Towards a Different Poetics of Women’s Writing teksty drugie · Institute of Literary Research Polish Academy of Science index 337412 · pl issn 0867-0633 EDITORIAL BOARD Agata Bielik-Robson (uk), Włodzimierz Bolecki, Maria Delaperrière (France), Ewa Domańska, Grzegorz Grochowski, Zdzisław Łapiński, Michał Paweł Markowski (usa), Maciej Maryl, Jakub Momro, Anna Nasiłowska (Deputy Editor-in-Chief), Leonard Neuger (Sweden), Ryszard Nycz (Editor-in-Chief), Bożena Shallcross (usa), Marta Zielińska, Tul’si Bhambry (English Translator and Language Consultant), Justyna Tabaszewska, Marta Bukowiecka (Managing Editor) ADVISORY BOARD Edward Balcerzan, Stanisław Barańczak (usa) , Małgorzata Czermińska, Paweł Dybel, Knut Andreas Grimstad (Norway), Jerzy Jarzębski, Bożena Karwowska (Canada), Krzysztof Kłosiński, Dorota Krawczyńska, Vladimir Krysinski (Canada), Luigi Marinelli (Italy), Arent van Nieukerken (the Netherlands), Ewa Rewers, German Ritz (Switzerland), Henryk Siewierski (Brasil), Janusz Sławiński , Ewa Thompson (usa), Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, -

Compassionate Ministry Reader English Version January 2005 Edition

Compassionate Ministry Reader English Version January 2005 Edition Prepared by Fletcher L. Tink, Ph.D. And Mindy Bowne Hancock Nazarene Compassionate Ministries Education 6401 The Paseo Kansas City, MO 64131 United States of America Email: [email protected] 2 Introduction The following materials have been compiled from a variety of sources gathered through the Office of Education, Nazarene Compassionate Ministries. They are drawn primarily from individual articles under the title of “Samarinating”, a coined word that combines the sense of “marinating” or “soaking over time in spices”, in other words, “enriching,” “flavoring,”— thinking and meditating over what it means to be a good Samaritan. These articles are gathered primarily to address the issues not only that face the world, but also that confront the Church of the Nazarene, to encourage its members and friends to take seriously the mandates of what it means to be a contributing member of the world community, a Christian and a Nazarene. At its bottom line, they call us to understand “Compassion as a Lifestyle.” The articles are intended to inform, stimulate, provoke, irritate, and energize readers to become “Lifestyle Christians” in all areas of personal and group accountability towards the poor and marginalized in all societies. This Reader is intended as a living and evolving document that will constantly adapt new contents as issues and inspiration come to us. In most cases, where an author is not specifically mentioned, the articles are written by Dr. Fletcher Tink, who has been employed by, and is contracted with Nazarene Compassionate Ministries International. Additionally, articles have been submitted by Mindy Bowne Hancock, Dr.