Traveler's Aid at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915 Eric C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE WRITINGS of BRITISH CONSCRIPT SOLDIERS, 1916-1918 Ilana Ruth Bet-El Submitted for the Degree of Ph

EXPERIENCE INTO IDENTITY: THE WRITINGS OF BRITISH CONSCRIPT SOLDIERS, 1916-1918 Ilana Ruth Bet-El Submitted for the degree of PhD University College London AB STRACT Between January 1916 and March 1919 2,504,183 men were conscripted into the British army -- representing as such over half the wartime enlistments. Yet to date, the conscripts and their contribution to the Great War have not been acknowledged or studied. This is mainly due to the image of the war in England, which is focused upon the heroic plight of the volunteer soldiers on the Western Front. Historiography, literary studies and popular culture all evoke this image, which is based largely upon the volumes of poems and memoirs written by young volunteer officers, of middle and upper class background, such as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. But the British wartime army was not a society of poets and authors who knew how to distil experience into words; nor, as mentioned, were all the soldiers volunteers. This dissertation therefore attempts to explore the cultural identity of this unknown population through a collection of diaries, letters and unpublished accounts of some conscripts; and to do so with the aid of a novel methodological approach. In Part I the concept of this research is explained, as a qualitative examination of all the chosen writings, with emphasis upon eliciting the attitudes of the writers to the factual events they recount. Each text -- e.g. letter or diary -- was read literally, and also in light of the entire collection, thus allowing for the emergence of personal and collective narratives concurrently. -

The Diplomatic Battle for the United States, 1914-1917

ACQUIRING AMERICA: THE DIPLOMATIC BATTLE FOR THE UNITED STATES, 1914-1917 Presented to The Division of History The University of Sheffield Fulfilment of the requirements for PhD by Justin Quinn Olmstead January 2013 Table of Contents Introduction 1: Pre-War Diplomacy 29 A Latent Animosity: German-American Relations 33 Britain and the U.S.: The Intimacy of Attraction and Repulsion 38 Rapprochement a la Kaiser Wilhelm 11 45 The Set Up 52 Advancing British Interests 55 Conclusion 59 2: The United States and Britain's Blockade 63 Neutrality and the Declaration of London 65 The Order in Council of 20 August 1914 73 Freedom of the Seas 83 Conclusion 92 3: The Diplomacy of U-Boat Warfare 94 The Chancellor's Challenge 96 The Chancellor's Decision 99 The President's Protest 111 The Belligerent's Responses 116 First Contact: The Impact of U-Boat Warfare 119 Conclusion 134 4: Diplomatic Acquisition via Mexico 137 Entering the Fray 140 Punitive Measures 145 Zimmerman's Gamble 155 Conclusion 159 5: The Peace Option 163 Posturing for Peace: 1914-1915 169 The House-Grey Memorandum 183 The German Peace Offer of 1916 193 Conclusion 197 6: Conclusion 200 Bibliography 227 Introduction Shortly after war was declared in August 1914 the undisputed leaders of each alliance, Great Britain and Gennany, found they were unable to win the war outright and began searching for further means to secure victory; the fonnation of a blockade, the use of submarines, attacking the flanks (Allied attacks in the Balkans and Baltic), Gennan Zeppelin bombardment of British coastal towns, and the diplomatic search for additional allies in an attempt to break the stalemate that had ensued soon after fighting had commenced. -

Special Libraries, January 1914 Special Libraries Association

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1914 Special Libraries, 1910s 1-1-1914 Special Libraries, January 1914 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1914 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, January 1914" (1914). Special Libraries, 1914. Book 1. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1914/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1910s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1914 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special Libraries Where the Special Library is a Necessity The scientific spirit is always that which seeks to learn all the facts on any one subject and when they are found strives to formulatc laws based on the facts and to put these laws into operation. It is a mark of the truly scientific spirit that it is impatient with those who assume a truth from a part only of the facts; or who initiate practice without that thorough comprehension of the laws of the subject which can only he had when all the facts are known and their rclntions determined. The advocates of what is now popularly called "Scientific Management" assert that they aim to learn the truth concerning factory production in all its varied phases and to base upon such study a practical system of standard industrial operation -Honorable William C. -

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 the Character of the German Offensive

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 359 the character of the German offensive became clear, and losses reached staggering levels, Joffre urgently demanded as early a start as possible to the allied offensive. In May he and Haig agreed to mount an assault on I July 'athwart the Somme.' Long before the starting date of the offensive had been fixed the British had been preparing for it by building up, behind their lines, the communications and logistical support the 'big push' demanded. Masses of materiel were accumulated close to the trenches, including nearly three million rounds of artillery ammuni tion. War on this scale was a major industrial undertaking.• Military aviation, of necessity, made a proportionate leap as well. The RFC had to expand to meet the demands of the new mass armies, and during the first six months of 1916 Trenchard, with Haig's strong support, strove to create an air weapon that could meet the challenge of the offensive. Beginning in January the RFC had been reorganized into brigades, one to each army, a process completed on 1 April when IV Brigade was formed to support the Fourth Army. Each brigade consisted of a headquarters, an aircraft park, a balloon wing, an army wing of two to four squadrons, and a corps wing of three to five squadrons (one squadron for each corps). At RFC Headquarters there was an additional wing to provide reconnais sance for GHQ, and, as time went on, to carry out additional fighting and bombing duties.3 Artillery observation was now the chief function of the RFC , with subsidiary efforts concentrated on close reconnaissance and photography. -

Cotton, Wheat, and the World War, 1914-1918: the Case of Oklahoma

COTTON, WHEAT, AND THE WORLD WAR, 1914-1918: THE CASE OF OKLAHOMA By STEVEN LEE ,,SEWELL Bachelor of Arts in Arts & Sciences Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1984 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 1986 )h~i.s \qe~ SSl~c., Q.ap. ;l._ /6rE-H'o~~ u - "''-1 ..., I (1,.,.,,. "-~~-. \\ I Vf·~. ,..--("' \, I ·Ii.::,>-./ -.i.~ ~. ''61·/,.... I ,l' ,_, .• ·. 'r.~1~ ' COTTON, WHEAT, AND THE WORLD WAR, . ...~ ..-~~~--·:....:.-/ 1914-1918: THE CASE OF OKLAHOMA Thesis Approved: 02 Gb Thesis Adviser °?j" 1 Dean of the Graduate College ii 1 27: . L S J PREFACE This work is a study of the cotton and wheat markets of the World War One era. Subjects including acreage, production, prices, and value of crops were studied. The relationship between the commodities producers and the government was also an area taken into consideration. The lobbying efforts of the cotton and wheat producers also were subjects for analysis. The study utilized figures on both national and state commodities production although the main subject of study was the impact of the World War upon the cotton and wheat markets of Oklahoma. I wish to express my sincere gratitude to all those associated with this study. In particular, I am especially indebted to my committee chairman, Dr. Roger Biles, who went above and beyond the call of duty in his assistance. I am also grateful for the help provided by my other committee members, Dr. John Sylvester and Dr. -

January 1914

January 1914 The Mifflinburg Telegraph newspapers of January 2 and January 9, 1914 were full of local, as well as national and international news. In the county The Union County Anti-Saloon League Delegate Convention held a meeting for delegates from the churches of Union County at the Presbyterian Church of Lewisburg on Tuesday, January 13, 1914. “The sense of the moral imperative should come upon the churches of Union County to use their power to eliminate the saloon and to send a man to the next Legislature true to the interests of Home Rule on the Liquor question.” Each church was entitled to send the pastor and two delegates. “Men, as delegates, should be sent, if practicable.” The organizers were I.P. Patch, W.M. Rearick and Bromley Smith. [The Anti-Saloon League coordinated the rural Protestant movement against alcohol. Prohibition, the ban on the sale, production, importation and transportation of alcoholic beverages was in place in the US from 1920 to 1933.] Weddings The White Deer valley saw two weddings at residents' homes in early January 1914. Charles A. Shireman, of Allenwood, wed Florence L. Miller at her parent's home, the Rev. S.F. Tholan of the Lutheran church officiating. Chas. S. Winner, of Montoursville and Sarah Wertz of White Deer were married by Rev W.W. Closer at Augustus Wertz's home. In Limestone Twp., Mr. and Mrs. Frank Buoy hosted the wedding of their daughter Harriet to Frank Anderson by Rev. H.L. Gerstmyer. Mr. and Mrs. Wm Bingaman's home near Laurelton was the site of the wedding of their daughter Ida May to Lester Elmer Johnson by Rev. -

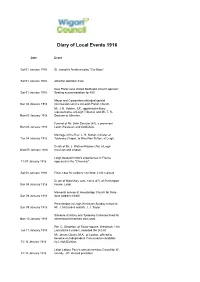

Diary of Local Events 1916

Diary of Local Events 1916 Date Event Sat 01 January 1916 St. Joseph's Amateurs play "Our Boys." Sat 01 January 1916 Atherton old folks' treat. New Plank Lane United Methodist Church opened: Sat 01 January 1916 Seating accommodation for 450. Mayor and Corporation attended special Sun 02 January 1916 intercession service at Leigh Parish Church. Mr. J. H. Holden, J.P., appointed military representative at Leigh Tribunal, and Mr. T. R. Mon 03 January 1916 Dootson at Atherton. Funeral of Mr. John Simister (61), a prominent Mon 03 January 1916 Leigh Wesleyan and Oddfellow. Marriage of the Rev. L. H. Nuttall, minister at Tue 04 January 1916 Tyldesley Chapel, to Miss Nan Sutton, of Leigh. Death of Mr. J. Watson Raynor (79), a Leigh Wed 05 January 1916 musician and clogger. Leigh despatch rider's experiences in France Fri 07 January 1916 appeared in the "Chronicle". Sat 08 January 1916 Flower day for soldiers' comforts: £140 realised Death of Miss Mary Jane Yates (47). of Pennington Sun 09 January 1916 House, Leigh. Memorial service at Howebridge Church for three Sun 09 January 1916 local soldiers (killed) Presentation at Leigh Wesleyan Sunday school to Sun 09 January 1916 Mr. J. McCardell and Mr. J. J. Taylor. Slackers at Astley and Tyldesley Collieries fined for Mon 10 January 1916 absenting themselves from work. Pte. G. Singleton, of Taylor-square, Westleigh, 11th Tue 11 January 1916 Lancashire Fusiliers, awarded the D.C.M. Mr. James Glover, M.A., of Lowton, offered to become an Independent Conservative candidate Fri 14 January 1916 for Leigh Division. -

World War I in 1916

MAJOR EVENTS AFFECTING THE COUNTY IN 1916 In a front line trench, France, World War I (Library of Congress, Washington) World War I in 1916 When war was declared on 4 August 1914, there were already over 25,000 Irishmen serving in the regular British Army with another 30,000 Irishmen in the reserve. As most of the great European powers were drawn into the War, it spread to European colonies all over the world. Donegal men found that they were fighting not only in Europe but also in Egypt and Mesopotamia as well as in Africa and on ships in the North Sea and in the Mediterranean. 1916 was the worst year of the war, with more soldiers killed this year than in any other year. By the end of 1916, stalemate on land had truly set in with both sides firmly entrenched. By now, the belief that the war would be ‘over by Christmas’ was long gone. Hope of a swift end to the war was replaced by knowledge of the true extent of the sacrifice that would have to be paid in terms of loss of life. Recruitment and Enlisting Recruitment meetings were held all over the County. In 1916, the Department of Recruiting in Ireland wrote to Bishop O’Donnell, in Donegal, requesting: “. that recruiting meetings might with advantage be held outside the Churches . after Mass on Sundays and Holidays.” 21 MAJOR EVENTS AFFECTING THE COUNTY IN 1916 Men from all communities and from all corners of County Donegal enlisted. They enlisted in the three new Army Divisions: the 10th (Irish), 16th (Irish) and the 36th (Ulster), which were established after the War began. -

A Most Thankless Job: Augustine Birrell As Irish

A MOST THANKLESS JOB: AUGUSTINE BIRRELL AS IRISH CHIEF SECRETARY, 1907-1916 A Dissertation by KEVIN JOSEPH MCGLONE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, R. J. Q. Adams Committee Members, David Hudson Adam Seipp Brian Rouleau Peter Hugill Head of Department, David Vaught December 2016 Major Subject: History Copyright 2016 Kevin McGlone ABSTRACT Augustine Birrell was a man who held dear the classical liberal principles of representative democracy, political freedom and civil liberties. During his time as Irish Chief Secretary from 1907-1916, he fostered a friendly working relationship with the leaders of the Irish Party, whom he believed would be the men to lead the country once it was conferred with the responsibility of self-government. Hundreds of years of religious and political strife between Ireland’s Nationalist and Unionist communities meant that Birrell, like his predecessors, took administrative charge of a deeply polarized country. His friendship with Irish Party leader John Redmond quickly alienated him from the Irish Unionist community, which was adamantly opposed to a Dublin parliament under Nationalist control. Augustine Birrell’s legacy has been both tarnished and neglected because of the watershed Easter Rising of 1916, which shifted the focus of the historiography of the period towards militant nationalism at the expense of constitutional politics. Although Birrell’s flaws as Irish Chief Secretary have been well-documented, this paper helps to rehabilitate his image by underscoring the importance of his economic, social and political reforms for a country he grew to love. -

The Times Supplements, 1910-1917

The Times Supplements, 1910-1917 Peter O’Connor Musashino University, Tokyo Peter Robinson Japan Women’s University, Tokyo 1 Overview of the collection Geographical Supplements – The Times South America Supplements, (44 [43]1 issues, 752 pages) – The Times Russian Supplements, (28 [27] issues, 576 pages) – The Japanese Supplements, (6 issues, 176 pages) – The Spanish Supplement , (36 pages, single issue) – The Norwegian Supplement , (24 pages, single issue) Supplements Associated with World War I – The French Yellow Book (19 Dec 1914, 32 pages) – The Red Cross Supplement (21 Oct 1915, 32 pages) – The Recruiting Supplement (3 Nov 1915, 16 pages) – War Poems from The Times, August 1914-1915 (9 August 1915, 16 pages) Special Supplements – The Divorce Commission Supplement (13 Nov 1912, 8 pages) – The Marconi Scandal Supplement (14 Jun 1913, 8 pages) 2 Background The Times Supplements published in this series comprise eighty-five largely geographically-based supplements, complemented by significant groups and single-issue supplements on domestic and international political topics, of which 83 are published here. Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (1865-1922), acquired The Times newspaper in 1908. In adding the most influential and reliable voice of the British establishment and of Imperially- fostered globalisation to his growing portfolio of newspapers and magazines, Northcliffe aroused some opposition among those who feared that he would rely on his seemingly infallible ear for the popular note and lower the tone and weaken the authority of The Times. Northcliffe had long hoped to prise this trophy from the control of the Walters family, convinced of his ability to make more of the paper than they had, and from the beginning applied his singular energy and intuition to improving the fortunes of ‘The Thunderer’. -

The Gavelyte, January 1915

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The aG velyte 1-1915 The aG velyte, January 1915 Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/gavelyte Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cedarville College, "The aG velyte, January 1915" (1915). The Gavelyte. 81. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/gavelyte/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aG velyte by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lane Theological ein1nary• Cincinnati, Ohio Modern Curriculum. Co-operation with University of Cincinnati for advanced degreas. Eighty-third year. Pres. William McKibbin. The N agley Studio Picture Framing Kodaks and Photo Supplies Cedarville, Ohio. N ya.ls Face Cream "'\V ith Peroxide A superior non-greasy nourishing skin tone soon absorbed-leaves no shine. Leaves the skin soft and beautiful-will not cause or promote the growth of hair. A delightful after-shave. Nyal Toilet Articles are Superior We Carry a Complete Line RICHARDS DRUG STORE "The best is none too good for the sick" Phone 203. Cedarville, Ohio. The Gavelyte VOL. IX JANUARY , 1914 NO. 4 Cedarville Clolege and the New School Law. Many of the graduates and former 1devoted to regular college work, and students of Cedarville College have the removal of the College to another taken up teaching as their chosen ,community, where 1better facilities work and many preEent students are lCould be obtained for conducting a looking forward to the same profes- lnormal training s·chool in which the sion. -

NJDARM: Collection Guide

NJDARM: Collection Guide - NEW JERSEY STATE ARCHIVES COLLECTION GUIDE Record Group: Governor Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924; served 1911-1913) Series: Correspondence, 1909-1914 Accession #: 1964.005, 2001.028, Unknown Series #: S3700001 Guide Date: 1987 (JK) Volume: 4.25 c.f. [9 boxes] Box 1 | Box 2 | Box 3 | Box 4 | Box 5 | Box 6 | Box 7 | Box 8 | Box 9 Contents Box 1 1. Item No. 1 to 3, 5 November - 20 December 1909. 2. Item No. 4 to 8, 13 - 24 January 1910. 3. Item No. 9 to 19, 25 January - 27 October 1910. 4. Item No. 20 to 28, 28 - 29 October 1910. 5. Item No. 29 to 36, 29 October - 1 November 1910. 6. Item No. 37 to 43, 1 - 12 November 1910. 7. Item No. 44 to 57, 16 November - 3 December 1910. 8. Item No. 58 to 78, November - 17 December 1910. 9. Item No. 79 to 100, 18 - 23 December 1910. 10. Item No. 101 to 116, 23 - 29 December 1910. 11. Item No. 117 to 133, 29 December 1910 - 2 January 1911. 12. Item No. 134 to 159, 2 - 9 January 1911. 13. Item No. 160 to 168, 9 - 11 January 1911. 14. Item No. 169 to 187, 12 - 13 January 1911. 15. Item No. 188 to 204, 12 - 15 January 1911. 16. Item No. 205 to 226, 16 - 17 January 1911. 17. Item No. 227 to 255, 18 - 19 January 1911. 18. Item No. 256 to 275, 18 - 20 January 1911. 19. Item No. 276 to 292, 20 - 21 January 1911.