THE WRITINGS of BRITISH CONSCRIPT SOLDIERS, 1916-1918 Ilana Ruth Bet-El Submitted for the Degree of Ph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House Publications

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86m3dcm No online items Inventory of the Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House publications Finding aid prepared by Trevor Wood Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008, 2014 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Great Britain. XX230 1 Foreign Office. Wellington House publications Title: Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House publications Date (inclusive): 1914-1918 Collection Number: XX230 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13 manuscript boxes, 5 card file boxes, 1 cubic foot box(6.2 Linear Feet) Abstract: Books, pamphlets, and miscellany, relating to World War I and British participation in it. Card file drawers at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives describe this collection. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House publications, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Historical Note Propaganda section of the British Foreign Office. Scope and Content of Collection Books, pamphlets, and miscellany, relating to World War I and British participation in it. Subjects and Indexing Terms World War, 1914-1918 -- Propaganda Propaganda, British World War, 1914-1918 -- Great Britain box 1 "The Achievements of the Zeppelins." By a Swede. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

American Armies and Battlefields in Europe

Chapter v1 THE AMERICAN BATTLEFIELDS NORTH OF PARIS chapter gives brief accounts of areas and to all of the American ceme- all American fighting whi ch oc- teries and monuments. This route is Thiscurred on the battle front north of recommended for those who desire to Paris and complete information concern- make an extended automobile tour in the ing the American military cemeteries and region. Starting from Paris, it can be monuments in that general region. The completely covered in four days, allowing military operations which are treated are plenty of time to stop on the way. those of the American lst, 27th, 30th, The accounts of the different operations 33d, 37th, 80th and 91st Divisions and and the descriptions of the American the 6th and 11 th Engineer Regiments. cemeteries and monuments are given in Because of the great distances apart of the order they are reached when following So uthern Encr ance to cb e St. Quentin Can al Tunnel, Near Bellicourc, October 1, 1918 the areas where this fighting occurred no the suggested route. For tbis reason they itinerary is given. Every operation is do not appear in chronological order. described, however, by a brief account Many American units otber tban those illustrated by a sketch. The account and mentioned in this chapter, sucb as avia- sketch together give sufficient information tion, tank, medical, engineer and infantry, to enable the tourist to plan a trip through served behind this part of the front. Their any particular American combat area. services have not been recorded, however, The general map on the next page as the space limitations of tbis chapter indicates a route wbich takes the tourist required that it be limited to those Amer- either int o or cl ose to all of tbese combat ican organizations which actually engaged (371) 372 THE AMERICAN B ATTLEFIELD S NO R TH O F PARIS Suggested Tour of American Battlefields North of Paris __ Miles Ghent ( î 37th and 91st Divisions, Ypres-Lys '"offensive, October 30-November 11, 1918 \ ( N \ 1 80th Division, Somme 1918 Albert 33d Division. -

October 1916

MEETING.- 4th OCTOBER 1916. A Meeting of tre County Council was held in the County Council Chamber, Courthouse, Wexford, on 4th October 1916. Present:- Mr John Bolger, (Chairman) presiding. A1so:- Lord Courtown, Messrs James Codd, N. J. Cowman, M. C1oney, L. Barry, Micbael Doyle, R. Scallan, A. Kinsella, Patrick O'Neill, J. S. Hearn, C. H. Peacocke, J. J. Kehoe, J. J. O'Byrne, J. T. MayleI', Joseph Redmond, T. As~l~, P. Keating. The Secretary, County Surveyor, and County Solicit»r, were also in attendo.nce. I _.9onfirmfttion of inutes, The Minutes of last Meeting were read and confirmed. Suspension of Standing Orders. The Ch&irm!:.m moved the suspe!lsion of the Stall in Orders to move some resolutions not on the Agenda. P per, and not directly connected with the business of t~e Counci1o , Pa.ssed. Vote of Condolence. The Ch&irm n moved, Mr Hearn seconded, the following reso1ution::- ttrrh&t we offer our esteemed colleague, lv"r J. A. Doyle, OUD heartfelt syrl1pa.th in the loss sustained by hio in the de th of his brother-Mr Jehn Doyleo" "Passed unanimously"o The Irish Parliamentary party. The Chairman moved the following:- tlrrhAt we the Members of the Wexford County Council desire to renew our confidence in Mr John Redmond, and the Irish Parliamentary Party, in the faco of the many scurrilous and unscrupulous ttacks which a.re made on them for the last five months. Considering all the great reforms that hav~ been granted to Ireland for th last thirty years by Constitutional agitation through the arduous and untiring efforts of the Irish Party, We are confident when the Home Rule Bill will come into operation that Mr Redmond ahd his followers will insist on a full © WEXFORD COUNTY COUNCIL ARCHIVES 2 measure for all ~reland, and not allow any ~artition. -

Traveler's Aid at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915 Eric C

Molloy College DigitalCommons@Molloy Faculty Works: History and Political Science 2015 Safeguarding the Innocent: Traveler's Aid at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915 Eric C. Cimino Ph.D. Molloy College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.molloy.edu/hps_fac Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons DigitalCommons@Molloy Feedback Recommended Citation Cimino, Eric C. Ph.D., "Safeguarding the Innocent: Traveler's Aid at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915" (2015). Faculty Works: History and Political Science. 2. https://digitalcommons.molloy.edu/hps_fac/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Molloy. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Works: History and Political Science by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Molloy. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Safeguarding the Innocent: Travelers’ Aid at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915 By Eric C. Cimino In January 1914, the editorial page of The San Diego Union promised that the upcoming Panama-California Exposition would usher in a “new era” in the city’s history. San Diego would “emerge from its semi-isolation…and take on the dignity of a metropolis, a great seaport, and a commercial center.” There was a dark side, however, to this anticipated transformation as the newspaper reported that the city would soon be overwhelmed with “thousands of strangers and to these will be added thousands of immigrants who will In 1912, San Diego’s YWCA helped visitors to find make this port their landing place.” safe housing and transit on their arrival in San Among the newcomers would be many Diego. -

The U.S., World War I, and Spreading Influenza in 1918

Online Office Hours We’ll get started at 2 ET Library of Congress Online Office Hours Welcome. We’re glad you’re here! Use the chat box to introduce yourselves. Let us know: Your first name Where you’re joining us from Why you’re here THE U.S., WORLD WAR I, AND SPREADING INFLUENZA IN 1918 Ryan Reft, historian of modern America in the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress Using LoC collections to research influenza pandemic 1918-1919 Woodrow Wilson, draft Fourteen Three main takeaways Points, 1918 • Demonstrate the way World War I facilitated the spread of the virus through mobilization • How the pandemic was fought domestically and its effects • Influenza’s possible impact on world events via Woodrow Wilson and the Treaty of Versailles U.S. in January 1918 Mobilization Military Map of the [USA], 1917 • Creating a military • Selective Service Act passed in May 1917 • First truly conscripted military in U.S. history • Creates military of four million; two million go overseas • Military camps set up across nation • Home front oriented to wartime production of goods • January 1918 Woodrow Wilson outlines his 14 points Straight Outta Kansas Camp Funston Camp Funston, Fort Riley, 1918 • First reported case of influenza in Haskell County, KS, February 1918 • Camp Funston (Fort Riley), second largest cantonment • 56,000 troops • Virus erupts there in March • Cold conditions, overcrowded tents, poorly heated, inadequate clothing The first of three waves • First wave, February – May, 1918 • Even if there was war … • “high morbidity, but low mortality” – Anthony Fauci, 2018 the war was removed • Americans carry over to Europe where it changes from us you know … on • Second wave, August – December the other side … This • Most lethal, high mortality esp. -

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 the Character of the German Offensive

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 359 the character of the German offensive became clear, and losses reached staggering levels, Joffre urgently demanded as early a start as possible to the allied offensive. In May he and Haig agreed to mount an assault on I July 'athwart the Somme.' Long before the starting date of the offensive had been fixed the British had been preparing for it by building up, behind their lines, the communications and logistical support the 'big push' demanded. Masses of materiel were accumulated close to the trenches, including nearly three million rounds of artillery ammuni tion. War on this scale was a major industrial undertaking.• Military aviation, of necessity, made a proportionate leap as well. The RFC had to expand to meet the demands of the new mass armies, and during the first six months of 1916 Trenchard, with Haig's strong support, strove to create an air weapon that could meet the challenge of the offensive. Beginning in January the RFC had been reorganized into brigades, one to each army, a process completed on 1 April when IV Brigade was formed to support the Fourth Army. Each brigade consisted of a headquarters, an aircraft park, a balloon wing, an army wing of two to four squadrons, and a corps wing of three to five squadrons (one squadron for each corps). At RFC Headquarters there was an additional wing to provide reconnais sance for GHQ, and, as time went on, to carry out additional fighting and bombing duties.3 Artillery observation was now the chief function of the RFC , with subsidiary efforts concentrated on close reconnaissance and photography. -

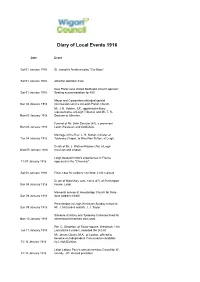

Diary of Local Events 1916

Diary of Local Events 1916 Date Event Sat 01 January 1916 St. Joseph's Amateurs play "Our Boys." Sat 01 January 1916 Atherton old folks' treat. New Plank Lane United Methodist Church opened: Sat 01 January 1916 Seating accommodation for 450. Mayor and Corporation attended special Sun 02 January 1916 intercession service at Leigh Parish Church. Mr. J. H. Holden, J.P., appointed military representative at Leigh Tribunal, and Mr. T. R. Mon 03 January 1916 Dootson at Atherton. Funeral of Mr. John Simister (61), a prominent Mon 03 January 1916 Leigh Wesleyan and Oddfellow. Marriage of the Rev. L. H. Nuttall, minister at Tue 04 January 1916 Tyldesley Chapel, to Miss Nan Sutton, of Leigh. Death of Mr. J. Watson Raynor (79), a Leigh Wed 05 January 1916 musician and clogger. Leigh despatch rider's experiences in France Fri 07 January 1916 appeared in the "Chronicle". Sat 08 January 1916 Flower day for soldiers' comforts: £140 realised Death of Miss Mary Jane Yates (47). of Pennington Sun 09 January 1916 House, Leigh. Memorial service at Howebridge Church for three Sun 09 January 1916 local soldiers (killed) Presentation at Leigh Wesleyan Sunday school to Sun 09 January 1916 Mr. J. McCardell and Mr. J. J. Taylor. Slackers at Astley and Tyldesley Collieries fined for Mon 10 January 1916 absenting themselves from work. Pte. G. Singleton, of Taylor-square, Westleigh, 11th Tue 11 January 1916 Lancashire Fusiliers, awarded the D.C.M. Mr. James Glover, M.A., of Lowton, offered to become an Independent Conservative candidate Fri 14 January 1916 for Leigh Division. -

Recent Publications Relating to Military Meteorology

40 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW. JANUARY,1918 Seeod Pan Amhnseientifi eongrees-continued. U. S. States relations service. Experiment station rmd. Wiwhington. Kullmer, C. J. Monthly storm frequency in the United States. v. $7. Noiyenibcr. 1917. 338-393. Richards, E. E. Dissolved oxygen in rain water. p. 6W21. 2ud, Robert DeC[ourcy]. The thunderstorms of the United [Abstract from Jour. agr. sci.] Statea as climatic phenomena. p. 393-411. Adniie des sciences. C‘omptea rendus. Pm.8. Tome 165. 24 dkm- Huntington, Ellsworth. Solar activity, cyclonic storms, and cli- bre 1917. matic changes. 411-431. Schaffers, V. Le son du canon h grande distance. p. 1057 1058. Cox, HeyI. Iniuence of the Great Lakes upon movement of Dunoyer L. & Reboul, G. Sur les variations diurnee du vent en hqh an ow pressure areas. p. 432-459. altitude. p. 1068-1071. Fassrg, Oliver L. Tropical rains-their duration, frequency, and Acadhnie de8 skes. Compte8 rendus. Pa&. Tonit 166. 21 jan&r intensity. 9. 4-73. 191s. Gab, htonio. Fluctuacionea climatol6gicas en loa tiempos Reboul, G. Relation entre lea variations barornhtriquea et cellea hidricos. 475481. du vent au sol: application la pr6vision. p. 124-126. Cline, Isaac Bf: Temperature conditions at New Orleans, 8.- in- Bureau ~nteniatwnalde8 poide et inesure8. !haaux et 7nkmches. Pa&. fluenced by subsurface drainage. p. 461-496. Tome 16. 1917. Church, J[ames] E., Jr. Snow eurveymg: ita blems and their Leduc, A. La maaae du litre d’air dana lee conditions normalea. present phasea with reference to Mount gel Nevada, and p: 7-37. [Introductory note b Ch. Ed. -

World War I in 1916

MAJOR EVENTS AFFECTING THE COUNTY IN 1916 In a front line trench, France, World War I (Library of Congress, Washington) World War I in 1916 When war was declared on 4 August 1914, there were already over 25,000 Irishmen serving in the regular British Army with another 30,000 Irishmen in the reserve. As most of the great European powers were drawn into the War, it spread to European colonies all over the world. Donegal men found that they were fighting not only in Europe but also in Egypt and Mesopotamia as well as in Africa and on ships in the North Sea and in the Mediterranean. 1916 was the worst year of the war, with more soldiers killed this year than in any other year. By the end of 1916, stalemate on land had truly set in with both sides firmly entrenched. By now, the belief that the war would be ‘over by Christmas’ was long gone. Hope of a swift end to the war was replaced by knowledge of the true extent of the sacrifice that would have to be paid in terms of loss of life. Recruitment and Enlisting Recruitment meetings were held all over the County. In 1916, the Department of Recruiting in Ireland wrote to Bishop O’Donnell, in Donegal, requesting: “. that recruiting meetings might with advantage be held outside the Churches . after Mass on Sundays and Holidays.” 21 MAJOR EVENTS AFFECTING THE COUNTY IN 1916 Men from all communities and from all corners of County Donegal enlisted. They enlisted in the three new Army Divisions: the 10th (Irish), 16th (Irish) and the 36th (Ulster), which were established after the War began. -

The Impact of the 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic on Virginia Stephanie Forrest Barker

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 2002 The impact of the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic on Virginia Stephanie Forrest Barker Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Barker, Stephanie Forrest, "The impact of the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic on Virginia" (2002). Master's Theses. Paper 1169. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of the 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic on Virginia By Stephanie Forrest Barker Master of Arts in History, University of Richmond, 2002 R. Barry Westin, Thesis Director In the fall of 1918 an unparalleled influenza pandemic spread throughout the world. More than a quarter of Americans became ill, and at least 600,000 died. For many Virginians, this was a time of acute crisis that only could be compared to the days of the Civil War. This thesis describes Spanish influenza's impact on Virginia, primarily focusing on the cities of Newport News, Richmond, and Roanoke. It details influenza's emergence in Virginia and explores how state and city officials dealt with this unprecedented epidemic. This study examines how the epidemic disrupted daily routines of life and overwhelmed the state's medical community. This thesis briefly discusses the effect that the segregation of races had on the spread of influenza and the role that women played in battling the epidemic. -

A Most Thankless Job: Augustine Birrell As Irish

A MOST THANKLESS JOB: AUGUSTINE BIRRELL AS IRISH CHIEF SECRETARY, 1907-1916 A Dissertation by KEVIN JOSEPH MCGLONE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, R. J. Q. Adams Committee Members, David Hudson Adam Seipp Brian Rouleau Peter Hugill Head of Department, David Vaught December 2016 Major Subject: History Copyright 2016 Kevin McGlone ABSTRACT Augustine Birrell was a man who held dear the classical liberal principles of representative democracy, political freedom and civil liberties. During his time as Irish Chief Secretary from 1907-1916, he fostered a friendly working relationship with the leaders of the Irish Party, whom he believed would be the men to lead the country once it was conferred with the responsibility of self-government. Hundreds of years of religious and political strife between Ireland’s Nationalist and Unionist communities meant that Birrell, like his predecessors, took administrative charge of a deeply polarized country. His friendship with Irish Party leader John Redmond quickly alienated him from the Irish Unionist community, which was adamantly opposed to a Dublin parliament under Nationalist control. Augustine Birrell’s legacy has been both tarnished and neglected because of the watershed Easter Rising of 1916, which shifted the focus of the historiography of the period towards militant nationalism at the expense of constitutional politics. Although Birrell’s flaws as Irish Chief Secretary have been well-documented, this paper helps to rehabilitate his image by underscoring the importance of his economic, social and political reforms for a country he grew to love.