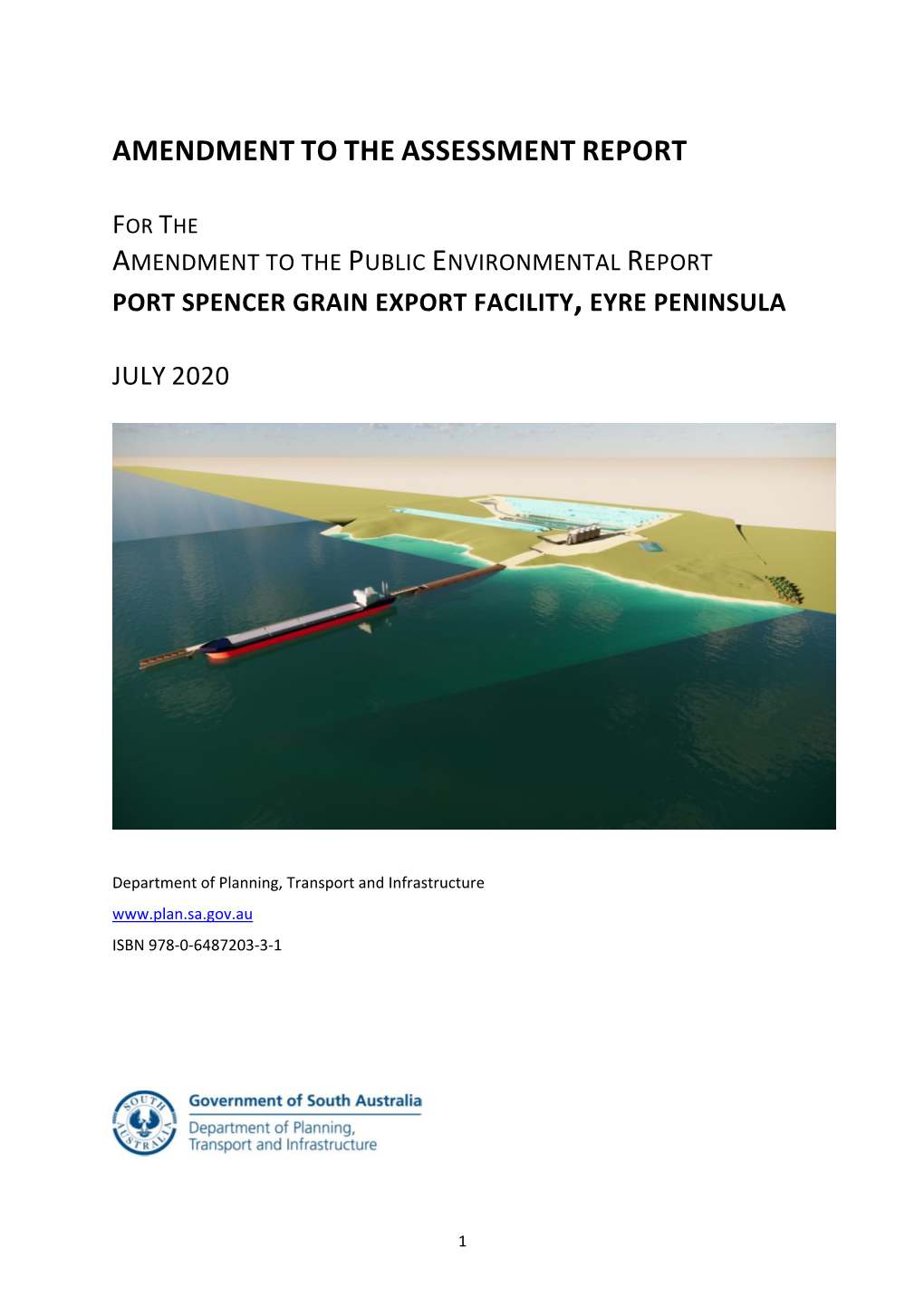

Amendment to the Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 June 2020

Period 1 April – 30 June 2020 Each year the Eyre Peninsula Landscape Board enters into a Service Level Agreement with the Department for Environment and Water (DEW) for the delivery of the Board’s programs plus services provided by business support and the regional management team. Details of the Board’s programs can be found in the Board’s Business Plan (2017-2020). This report provides a quarterly update of each program, including: Program highlights this period Local government engagement for this period Upcoming priorities for the next period Each milestone is assigned a status, based on its current progress. On track to deliver On track to deliver most milestones. Unlikely to meet all milestones. May be some delays. milestones. Further details of each of these programs can be found on the Eyre Peninsula Landscape Board website or by contacting Tim Breuer (Team Leader, Landscape Operations - Eastern District) for projects in the City Council of Whyalla and District Councils of Kimba, Franklin Harbor and Cleve areas on 0488 000 481. Eyre Peninsula Landscape Board 1 SLA Quarterly Report Eastern District Landscapes Milestones Status Conserving and protecting species and ecosystems Improving community skills, knowledge and engagement in landscapes management Program highlights this period EP Blue Gum tree planting Staff, volunteers, school students, and landholders planted around 450 EP Blue Gum (Eucalyptus petiolaris) trees in the Cleve district during the month of June. Three hundred and fifty trees were planted in a 1 km stretch of fenced area along a creek line on Turnbull’s private farm in the Cleve Hills. A further fifty were planted along a fenced creek-line alongside an already occurring EP Blue Gum community at Paul Harris’s farm at Gum-Flat. -

Port Spencer Grain Export Facility Peninsula Ports

Port Spencer Grain Export Facility Peninsula Ports Amendment to Public Environmental Report IW219900-0-NP-RPT-0003 | 2 8 November 2019 Amend ment to Pu blic Envir onm ental Rep ort Peninsula P orts Amendment to Public Environmental Report Port Spencer Grain Export Facility Project No: IW219900 Document Title: Amendment to Public Environmental Report Document No.: IW219900-0-NP-RPT-0003 Revision: 2 Date: 8 November 2019 Client Name: Peninsula Ports Client No: Client Reference Project Manager: Scott Snedden Author: Alana Horan File Name: J:\IE\Projects\06_Central West\IW219900\21 Deliverables\AMENDMENT TO THE PER\Amendment to PER_Rev 2.docx Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited ABN 37 001 024 095 Level 3, 121 King William Street Adelaide SA 5000 Australia www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2020 Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved H 31.10.2019 Draft AH NB SS 0 1.11.2019 Draft issued to DPTI AH SS DM 1 8.11.2019 Issued to DPTI AH SS DM 2 13.1.2020 Re-issued Volume 1 to DPTI. -

EPLGA Draft Special Meeting Minutes 16 Dec 15.Docx 1

Minutes of the Eyre Peninsula Local Government Association Board Special Meeting held by teleconference on Wednesday 16 December 2015 commencing at 9.00 am. Delegates Present: Sam Telfer (Deputy Chair) Vice President, EPLGA – Chaired the meeting Tom Antonio Deputy Mayor, City of Whyalla Don Millard Deputy Mayor, District Council Of Lower EP Allan Suter Mayor, District Council of Ceduna Roger Nield Mayor, District Council of Cleve David Allchurch Councillor,, District Council of Elliston Chris Smith CEO, District Council of Franklin Harbour Dean Johnson Mayor, District Council of Kimba Neville Starke Deputy Mayor, City of Port Lincoln Sherron MacKenzie Mayor, District Council of Streaky Bay Trevor Smith CEO, District Council of Tumby Bay Eleanor Scholz Mayor, Wudinna District Council Guests/Observers: Tony Irvine Executive Officer, EPLGA Geoffrey Moffatt CEO, District Council of Ceduna Peter Arnold CEO, District Council of Cleve Phil Cameron CEO, District Council of Elliston Rod Pearson CEO, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Rob Donaldson CEO, City of Port Lincoln Alan McGuire CEO, Wudinna District Council Daryl Cearns CEO, District Council of Kimba Deb Larwood Manager Corporate Services, District Council of Kimba 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Welcome/Apologies Deputy Chair Sam Telfer welcomed Board Members and other representatives.. Apologies received from: Jim Pollock Mayor, City of Whyalla Bruce Green Mayor, City of Port Lincoln Julie Low Mayor, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Kym Callaghan Chairman, District Council of Elliston -

Eyre Peninsula

RAA Regional Road Assessment Eyre Peninsula February 2015 Prepared By Chris Whisson Date 22 January 2015 Traffic and Road Safety Officer T: 08 8202 4743 E: [email protected] Ian Bishop Traffic Engineer T: 08 8202 4703 E: [email protected] Approved By Charles Mountain Date 13 February 2015 Senior Manager Road Safety T: 08 8202 4568 E: [email protected] Revision History Rev Date Author Approver Comment 0 24/12/2014 CW / IAB CM Draft. A 13/02/15 CW / IAB CM For Issue. B 02/03/15 CW / IAB CM Formatting corrections. Contents Executive Summary 1 1 Traffic Volumes 4 2 Crash Map 5 3 Lincoln Highway 7 3.1 Traffic Volumes 7 3.2 Crash History 7 3.3 Eyre Highway to Whyalla 9 3.3.1 Lane Widths and Lines 9 3.3.2 Signs and Delineation 9 3.3.3 Pavement Condition 9 3.3.4 Roadside Hazards 9 3.3.5 Recommendations 10 3.4 Whyalla to Cowell 10 3.4.1 Lane Widths and Lines 11 3.4.2 Signs and Delineation 11 3.4.3 Pavement Condition 11 3.4.4 Roadside Hazards 11 3.4.5 Recommendations 12 3.5 Cowell to Arno Bay 12 3.5.1 Lane Widths and Lines 12 3.5.2 Signs and Delineation 13 3.5.3 Pavement Condition 13 3.5.4 Roadside Hazards 13 3.5.5 Recommendations 13 3.6 Arno Bay to Port Lincoln 13 3.6.1 Lane Widths and Lines 14 3.6.2 Signs and Delineation 14 3.6.3 Pavement Condition 14 3.6.4 Roadside Hazards 14 3.6.5 Recommendations 15 4 Flinders Highway 16 4.1 Traffic Volumes 16 4.2 Crash History 16 4.3 Port Lincoln to Elliston 18 4.3.1 Lane Widths and Lines 18 4.3.2 Signs and Delineation 18 4.3.3 Pavement Condition 19 4.3.4 Roadside Hazards 19 4.3.5 Recommendations 20 -

Appendix I: Traffic Impact Assessment

Central Eyre Iron Project Mining Lease Proposal APPENDIX I TRAFFIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT COPYRIGHT Copyright © IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited, 2015 All rights reserved This document and any related documentation is protected by copyright owned by IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. The content of this document and any related documentation may only be copied and distributed for purposes of section 35A of the Mining Act, 1971 (SA) and otherwise with the prior written consent of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. DISCLAIMER A declaration has been made on behalf of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd by its Managing Director that he has taken reasonable steps to review the information contained in this document and to ensure its accuracy as at 5 November 2015. Subject to that declaration: (a) in writing this document, Iron Road Limited has relied on information provided by specialist consultants, government agencies, and other third parties. Iron Road Limited has reviewed all information to the best of its ability but does not take responsibility for the accuracy or completeness; and (b) this document has been prepared for information purposes only and, to the full extent permitted by law, Iron Road Limited, in respect of all persons other than the relevant government departments, makes no representation and gives no warranty or undertaking, express or implied, in respect to the information contained herein, and does not accept responsibility and is not liable for any loss or liability whatsoever arising as a result of any person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained within it. -

Business Plan Performance and Progress Reporting 2018-2019 July – December 2018

Business Plan Performance and Progress Reporting 2018-2019 July – December 2018 Contents Strategies Index ................................................................................................ 1 COMMUNITY AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ................................................................ 6 1.1 Employment and Skills ................................................................................ 6 1.2 Indigenous Development ......................................................................... 13 1.3 Social and Community ............................................................................. 18 1.4 Education and Training ............................................................................ 22 1.5 Health ...................................................................................................... 24 ECONOMIC AND BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT .............................................................. 29 2.1 Infrastructure .......................................................................................... 29 2.2 Economic and Business Diversity ............................................................. 32 2.3 Visitor Economy ...................................................................................... 38 2.4 Water Resources ...................................................................................... 44 2.5 Energy .................................................................................................... 47 2.6 Mining and Resource Manufacturing ...................................................... -

Eyre Peninsula Local Government Association

EYRE PENINSULA LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION Minutes of the Eyre Peninsula Local Government Association Board Meeting held at Wudinna Telecentre, 44 Eyre Highway, Wudinna on Friday 28th June 2013, commencing at 11am. BOARD MEMBERS PRESENT Julie Low (Chair) President, EPLGA Roger Nield Mayor, District Council of Cleve Eddie Elleway Mayor, District Council of Franklin Harbour Eleanor Scholz Chairperson, Wudinna District Council Pat Clark Chairperson, District Council of Elliston Bruce Green Mayor, City of Port Lincoln Jim Pollock Mayor, City of Whyalla John Schaefer Mayor, District Council of Kimba Laurie Collins Mayor, District Council of Tumby Bay Allan Suter Mayor, District Council of Ceduna Rob Stephens Mayor, District Council of Streaky Bay GUESTS / OBSERVERS Tony Irvine Exec Officer, EPLGA Peter Arnold CEO, District Council of Cleve Rob Foster CEO, District Council of Elliston Terry Barnes CEO, District Council of Franklin Harbour Daryl Cearns CEO, District Council of Kimba Lachlan Miller CEO, District Council of Streaky Bay Dion Watson Deputy CEO, District Council of Tumby Bay Trevor Smith CEO, District Council of Tumby Bay Geoff Dodd CEO, City of Port Lincoln Geoff Moffatt CEO, District Council of Ceduna Allan McGuire CEO, Wudinna District Council Deb Larwood Manager Corporate Services, District Council of Kimba Rod Pearson CEO, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Annie Lane Regional Manager, EPNRM Alex Todd Acting CEO, RDAWEP Paul Yeomans Superintendent SAPOL, Eyre & Western Rob Ackland CEO, LGA Procurement Helen Psarras Zone Emergency Management Project Officer (SA Fire and Emergency Services Commission) Neville Scholz Deputy Chairperson, DC Wudinna Merton Hodge Councillor, City of Whyalla Adil Jamil City Engineer, City of Whyalla Murray Mason Deputy Mayor, DC Tumby Bay Dean Johnson Deputy Mayor, DC Kimba Rob Ackland CEO LGA Procurement George Kolminski Country Fire Service Justin Woolford Country Fire Service Wendy Campana Executive Officer, LGA of SA Andrew Haste Director Member Services, LGA of SA 1. -

Appendix I: Traffic Impact Assessment

Central Eyre Iron Project Mining Lease Proposal APPENDIX I TRAFFIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT COPYRIGHT Copyright © IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited, 2015 All rights reserved This document and any related documentation is protected by copyright owned by IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. The content of this document and any related documentation may only be copied and distributed for purposes of section 35A of the Mining Act, 1971 (SA) and otherwise with the prior written consent of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. DISCLAIMER A declaration has been made on behalf of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd by its Managing Director that he has taken reasonable steps to review the information contained in this document and to ensure its accuracy as at 5 November 2015. Subject to that declaration: (a) in writing this document, Iron Road Limited has relied on information provided by specialist consultants, government agencies, and other third parties. Iron Road Limited has reviewed all information to the best of its ability but does not take responsibility for the accuracy or completeness; and (b) this document has been prepared for information purposes only and, to the full extent permitted by law, Iron Road Limited, in respect of all persons other than the relevant government departments, makes no representation and gives no warranty or undertaking, express or implied, in respect to the information contained herein, and does not accept responsibility and is not liable for any loss or liability whatsoever arising as a result of any person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained within it. -

Appendix W: Traffic Impact Assessment

Central Eyre Iron Project Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX W TRAFFIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT COPYRIGHT Copyright © Iron Road Limited, 2015 All rights reserved This document and any related documentation is protected by copyright owned by Iron Road Limited. The content of this document and any related documentation may only be copied and distributed for the purposes of section 46B of the Development Act, 1993 (SA) and otherwise with the prior written consent of Iron Road Limited. DISCLAIMER Iron Road Limited has taken all reasonable steps to review the information contained in this document and to ensure its accuracy as at the date of submission. Note that: (a) in writing this document, Iron Road Limited has relied on information provided by specialist consultants, government agencies, and other third parties. Iron Road Limited has reviewed all information to the best of its ability but does not take responsibility for the accuracy or completeness; and (b) this document has been prepared for information purposes only and, to the full extent permitted by law, Iron Road Limited, in respect of all persons other than the relevant government departments, makes no representation and gives no warranty or undertaking, express or implied, in respect to the information contained herein, and does not accept responsibility and is not liable for any loss or liability whatsoever arising as a result of any person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained within it. Central Eyre Iron Project IRON ROAD LIMITED Transport Impact Assessment -

Chapter 1: Introduction

Central Eyre Iron Project Environmental Impact Statement CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION COPYRIGHT Copyright © Iron Road Limited, 2015 All rights reserved This document and any related documentation is protected by copyright owned by Iron Road Limited. The content of this document and any related documentation may only be copied and distributed for the purposes of section 46B of the Development Act, 1993 (SA) and otherwise with the prior written consent of Iron Road Limited. DISCLAIMER Iron Road Limited has taken all reasonable steps to review the information contained in this document and to ensure its accuracy as at the date of submission. Note that: (a) in writing this document, Iron Road Limited has relied on information provided by specialist consultants, government agencies, and other third parties. Iron Road Limited has reviewed all information to the best of its ability but does not take responsibility for the accuracy or completeness; and (b) this document has been prepared for information purposes only and, to the full extent permitted by law, Iron Road Limited, in respect of all persons other than the relevant government departments, makes no representation and gives no warranty or undertaking, express or implied, in respect to the information contained herein, and does not accept responsibility and is not liable for any loss or liability whatsoever arising as a result of any person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained within it. 1 Introduction ........................................................... 1-1 1.1 Iron Road Company Profile ...................................................................................................... 1-2 1.2 History of the CEIP ................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.2.1 Environmental Policy ............................................................................................... -

Chapter 8: Traffic

Central Eyre Iron Project Mining Lease Proposal CHAPTER 8: TRAFFIC CHAPTER 8 TRAFFIC COPYRIGHT Copyright © IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited, 2015 All rights reserved This document and any related documentation is protected by copyright owned by IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. The content of this document and any related documentation may only be copied and distributed for purposes of section 35A of the Mining Act, 1971 (SA) and otherwise with the prior written consent of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. DISCLAIMER A declaration has been made on behalf of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd by its Managing Director that he has taken reasonable steps to review the information contained in this document and to ensure its accuracy as at 5 November 2015. Subject to that declaration: (a) in writing this document, Iron Road Limited has relied on information provided by specialist consultants, government agencies, and other third parties. Iron Road Limited has reviewed all information to the best of its ability but does not take responsibility for the accuracy or completeness; and (b) this document has been prepared for information purposes only and, to the full extent permitted by law, Iron Road Limited, in respect of all persons other than the relevant government departments, makes no representation and gives no warranty or undertaking, express or implied, in respect to the information contained herein, and does not accept responsibility and is not liable for any loss or liability whatsoever arising as a result of any person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained within it. -

Chapter 1: Introduction

Central Eyre Iron Project Mining Lease Proposal CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION COPYRIGHT Copyright © IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited, 2015 All rights reserved This document and any related documentation is protected by copyright owned by IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. The content of this document and any related documentation may only be copied and distributed for purposes of section 35A of the Mining Act, 1971 (SA) and otherwise with the prior written consent of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd and Iron Road Limited. DISCLAIMER A declaration has been made on behalf of IRD Mining Operations Pty Ltd by its Managing Director that he has taken reasonable steps to review the information contained in this document and to ensure its accuracy as at 5 November 2015. Subject to that declaration: (a) in writing this document, Iron Road Limited has relied on information provided by specialist consultants, government agencies, and other third parties. Iron Road Limited has reviewed all information to the best of its ability but does not take responsibility for the accuracy or completeness; and (b) this document has been prepared for information purposes only and, to the full extent permitted by law, Iron Road Limited, in respect of all persons other than the relevant government departments, makes no representation and gives no warranty or undertaking, express or implied, in respect to the information contained herein, and does not accept responsibility and is not liable for any loss or liability whatsoever arising as a result of any person acting or refraining from acting on any information contained within it.