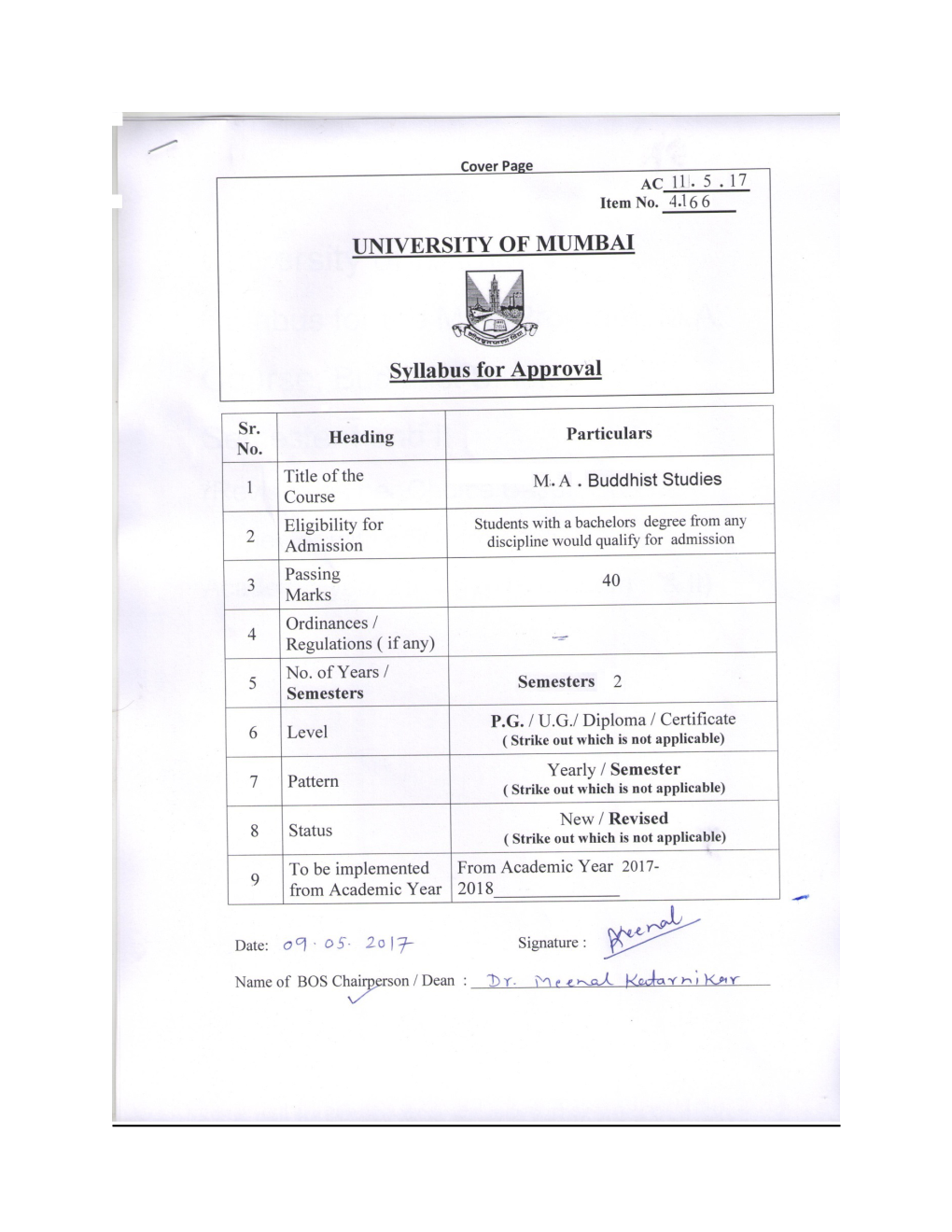

4.166 M.A. Buddhisht Studies Sem I & II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Dominique Townsend All rights reserved ABSTRACT Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend This dissertation investigates the relationships between Buddhism and culture as exemplified at Mindroling Monastery. Focusing on the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, I argue that Mindroling was a seminal religio-cultural institution that played a key role in cultivating the ruling elite class during a critical moment of Tibet’s history. This analysis demonstrates that the connections between Buddhism and high culture have been salient throughout the history of Buddhism, rendering the project relevant to a broad range of fields within Asian Studies and the Study of Religion. As the first extensive Western-language study of Mindroling, this project employs an interdisciplinary methodology combining historical, sociological, cultural and religious studies, and makes use of diverse Tibetan sources. Mindroling was founded in 1676 with ties to Tibet’s nobility and the Fifth Dalai Lama’s newly centralized government. It was a center for elite education until the twentieth century, and in this regard it was comparable to a Western university where young members of the nobility spent two to four years training in the arts and sciences and being shaped for positions of authority. This comparison serves to highlight commonalities between distant and familiar educational models and undercuts the tendency to diminish Tibetan culture to an exoticized imagining of Buddhism as a purely ascetic, world renouncing tradition. -

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

BYJU's IAS Comprehensive News Analysis

Post-Mauryan Age - Crafts, Trade & Towns [Ancient History Notes] After the fall of the Mauryan Empire, many other smaller states emerged in India, some of which are the Sungas, the Kanvas, the Satavahanas, etc. It is an important period in the ancient history of India and in hence, important for the UPSC exam. In this article, you can read all about the crafts, trade and towns in Post-Mauryan India. Post-Mauryan Age - Crafts The age of the Shakas, the Kushanas, the Satavahanas (200 BCE - 200 CE) and the first Tamil states was the most flourishing period in the history of crafts and commerce in ancient India. • The Digha-Nikaya, which belongs to the pre-Mauryan times, mentions nearly two dozen occupations but the Mahavastu, which belongs to this period, catalogues 36 different kinds of workers living in the town of Rajgir. • The Milinda Panho (the questions of Milinda) mentions about 75 occupations, out of which 60 are connected with various kinds of crafts. • Craftsmen are mostly associated with towns in literary texts, but some excavations show that they also inhabited villages. • The field of mining and metallurgy made great advancements and specializations, as many as eight crafts were associated with the working of gold, silver, lead, tin, copper, brass, iron, precious stones and jewels. o The technological advancement in iron manufacturing is evident by the excavations of specialized iron artifacts from the Karimnagar and Nalgonda districts of the Telangana region. o Indian iron and steel including cutlery were exported to Abyssinian ports and enjoyed great prestige in western Asia. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 329 4th International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2019) Study on Conceptual Precision and the Limited Applicability of "Truth", "Theory" and "Practice" to Indian Philosophical Traditions* Andrei V. Paribok Department of Cultural Studies and Philosophy of the East Institute of Philosophy St. Petersburg State University St. Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The paper treats some conceptual problems of English Dictionary” provides us with a plain and naive adequate translation of the Indian traditional philosophical lexicographical translation of sacca as “real, true”. In English, texts. A certain deficiency of Western philosophical “true” and “truth” as strict terms both mean primarily either a background which is rather often case among the translators statement (“He does not tell us the truth about the event”) or of these texts into European languages sometimes results in a bit metaphorically a mental state (E.g. “He knows the truth terminological vagueness and semantic misinterpretation of the about the event, but keeps silence”) but not the event referred most crucial concepts of the Indian thought. It is rigorously to, which deserves to be designated “real”. It is only true that demonstrated that the Buddha did not intend to proclaim any meanings “true” and “real” are often confounded in a casual “noble truths” but that his task was to explain the chief conversation, in ancient India as well as modern English. Yet, characteristics of the human reality and appropriate attitudes sacca is not only an everyday colloquial word. It is actually towards them. -

Mahayana Buddhism: the Doctrinal Foundations, Second Edition

9780203428474_4_001.qxd 16/6/08 11:55 AM Page 1 1 Introduction Buddhism: doctrinal diversity and (relative) moral unity There is a Tibetan saying that just as every valley has its own language so every teacher has his own doctrine. This is an exaggeration on both counts, but it does indicate the diversity to be found within Buddhism and the important role of a teacher in mediating a received tradition and adapting it to the needs, the personal transformation, of the pupil. This divers- ity prevents, or strongly hinders, generalization about Buddhism as a whole. Nevertheless it is a diversity which Mahayana Buddhists have rather gloried in, seen not as a scandal but as something to be proud of, indicating a richness and multifaceted ability to aid the spiritual quest of all sentient, and not just human, beings. It is important to emphasize this lack of unanimity at the outset. We are dealing with a religion with some 2,500 years of doctrinal development in an environment where scho- lastic precision and subtlety was at a premium. There are no Buddhist popes, no creeds, and, although there were councils in the early years, no attempts to impose uniformity of doctrine over the entire monastic, let alone lay, establishment. Buddhism spread widely across Central, South, South-East, and East Asia. It played an important role in aiding the cultural and spiritual development of nomads and tribesmen, but it also encountered peoples already very culturally and spiritually developed, most notably those of China, where it interacted with the indigenous civilization, modifying its doctrine and behaviour in the process. -

Metaphor and Literalism in Buddhism

METAPHOR AND LITERALISM IN BUDDHISM The notion of nirvana originally used the image of extinguishing a fire. Although the attainment of nirvana, ultimate liberation, is the focus of the Buddha’s teaching, its interpretation has been a constant problem to Buddhist exegetes, and has changed in different historical and doctrinal contexts. The concept is so central that changes in its understanding have necessarily involved much larger shifts in doctrine. This book studies the doctrinal development of the Pali nirvana and sub- sequent tradition and compares it with the Chinese Agama and its traditional interpretation. It clarifies early doctrinal developments of nirvana and traces the word and related terms back to their original metaphorical contexts. Thereby, it elucidates diverse interpretations and doctrinal and philosophical developments in the abhidharma exegeses and treatises of Southern and Northern Buddhist schools. Finally, the book examines which school, if any, kept the original meaning and reference of nirvana. Soonil Hwang is Assistant Professor in the Department of Indian Philosophy at Dongguk University, Seoul. His research interests are focused upon early Indian Buddhism, Buddhist Philosophy and Sectarian Buddhism. ROUTLEDGE CRITICAL STUDIES IN BUDDHISM General Editors: Charles S. Prebish and Damien Keown Routledge Critical Studies in Buddhism is a comprehensive study of the Buddhist tradition. The series explores this complex and extensive tradition from a variety of perspectives, using a range of different methodologies. The series is diverse in its focus, including historical studies, textual translations and commentaries, sociological investigations, bibliographic studies, and considera- tions of religious practice as an expression of Buddhism’s integral religiosity. It also presents materials on modern intellectual historical studies, including the role of Buddhist thought and scholarship in a contemporary, critical context and in the light of current social issues. -

Ontology of Consciousness

Ontology of Consciousness Percipient Action edited by Helmut Wautischer A Bradford Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ( 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or me- chanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] or write to Special Sales Depart- ment, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans on 3B2 by Asco Typesetters, Hong Kong, and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ontology of consciousness : percipient action / edited by Helmut Wautischer. p. cm. ‘‘A Bradford book.’’ Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-23259-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-262-73184-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Consciousness. 2. Philosophical anthropology. 3. Culture—Philosophy. 4. Neuropsychology— Philosophy. 5. Mind and body. I. Wautischer, Helmut. B105.C477O58 2008 126—dc22 2006033823 10987654321 Index Abaluya culture (Kenya), 519 as limitation of Turing machines, 362 Abba Macarius of Egypt, 166 as opportunity, 365, 371 Abhidharma in dualism, person as extension of matter, as guides to Buddhist thought and practice, 167, 454 10–13, 58 in focus of attention, 336 basic content, 58 in measurement of intervals, 315 in Asanga’s ‘‘Compendium of Abhidharma’’ in regrouping of elements, 335, 344 (Abhidharma-samuccaya), 67 in technical causality, 169, 177 in Maudgalyayana’s ‘‘On the Origin of shamanic separation from body, 145 Designations’’ Prajnapti–sastra,73 Action, 252–268. -

Buddha Speaks Mahayana Sublime Treasure King Sutra (Also Known As:) Avalokitesvara-Guna-Karanda-Vyuha Sutra Karanda-Vyuha Sutra

Buddha speaks Mahayana Sublime Treasure King Sutra (Also known as:) Avalokitesvara-guna-karanda-vyuha Sutra Karanda-vyuha Sutra (Tripitaka No. 1050) Translated during the Song Dynasty by Kustana Tripitaka Master TinSeekJoy Chapter 1 Thus I have heard: At one time, the Bhagavan was in the Garden of the Benefactor of Orphans and the Solitary, in Jeta Grove, (Jetavana Anathapindada-arama) in Sravasti state, accompanied by 250 great Bhiksu(monk)s, and 80 koti Bodhisattva-Mahasattvas, whose names are: Vajra-pani(Diamond-Hand) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Wisdom-Insight Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Vajra-sena(Diamond-Army) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Secret- Store Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Akasa-garbha(Space-Store) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Sun- Store Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Immovable Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Ratna- pani(Treasure-Hand) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Samanta-bhadra(Universal-Goodness) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Achievement of Reality and Eternity Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Eliminate-Obstructions(Sarva-nivaraNaviskambhin) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Great Diligence and Bravery Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Bhaisajya-raja(Medicine-King) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Avalokitesvara(Contemplator of the Worlds' Sounds) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Vajra-dhara(Vajra-Holding) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Ocean- Wisdom Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Dharma-Upholding Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, and so on. At that time, there were also many gods of the 32 heavens, leaded by Mahesvara(Great unrestricted God) and Narayana, came to join the congregation. They are: Sakra Devanam Indra the god of heavens, Great -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

Buddhism As a Pragmatic Religious Tradition

CHAPTER 1 Introduction: Buddhism as a Pragmatic Religious Tradition Our approach to Religion can be called “vernacular” . [It is] concerned with the kinds of data that may, even- tually, be able to give us some substantial insight into how religions have played their part in history, affect- ing people’s ability to respond to environmental crises; to earthquakes, floods, famines, pandemics; as well as to social ills and civil wars. Besides these evils, there are the everyday difficulties and personal disasters we all face from time to time. Religions have played their part in keeping people sane and stable....We thus see religions as an integral part of vernacular history, as a strand woven into lives of individuals, families, social groups, and whole societies. Religions are like technol- ogy in that respect: ever present and influential to peo- ple’s ability to solve life’s problems day by day. Vernon Reynolds and Ralph Tanner, The Social Ecology of Religion The Buddhist faith expresses itself most authentically in the processions of statues through towns, the noc- turnal illuminations in the streets and countryside. It is on such occasions that communion between the reli- gious and laity takes place . without which the religion could be no more than an exercise of recluse monks. Jacques Gernet, Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries 1 2 Popular Buddhist Texts from Nepal Whosoever maintains that it is karma that injures beings, and besides it there is no other reason for pain, his proposition is false.... Milindapañha IV.I.62 Health, good luck, peace, and progeny have been the near- universal wishes of humanity. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture.