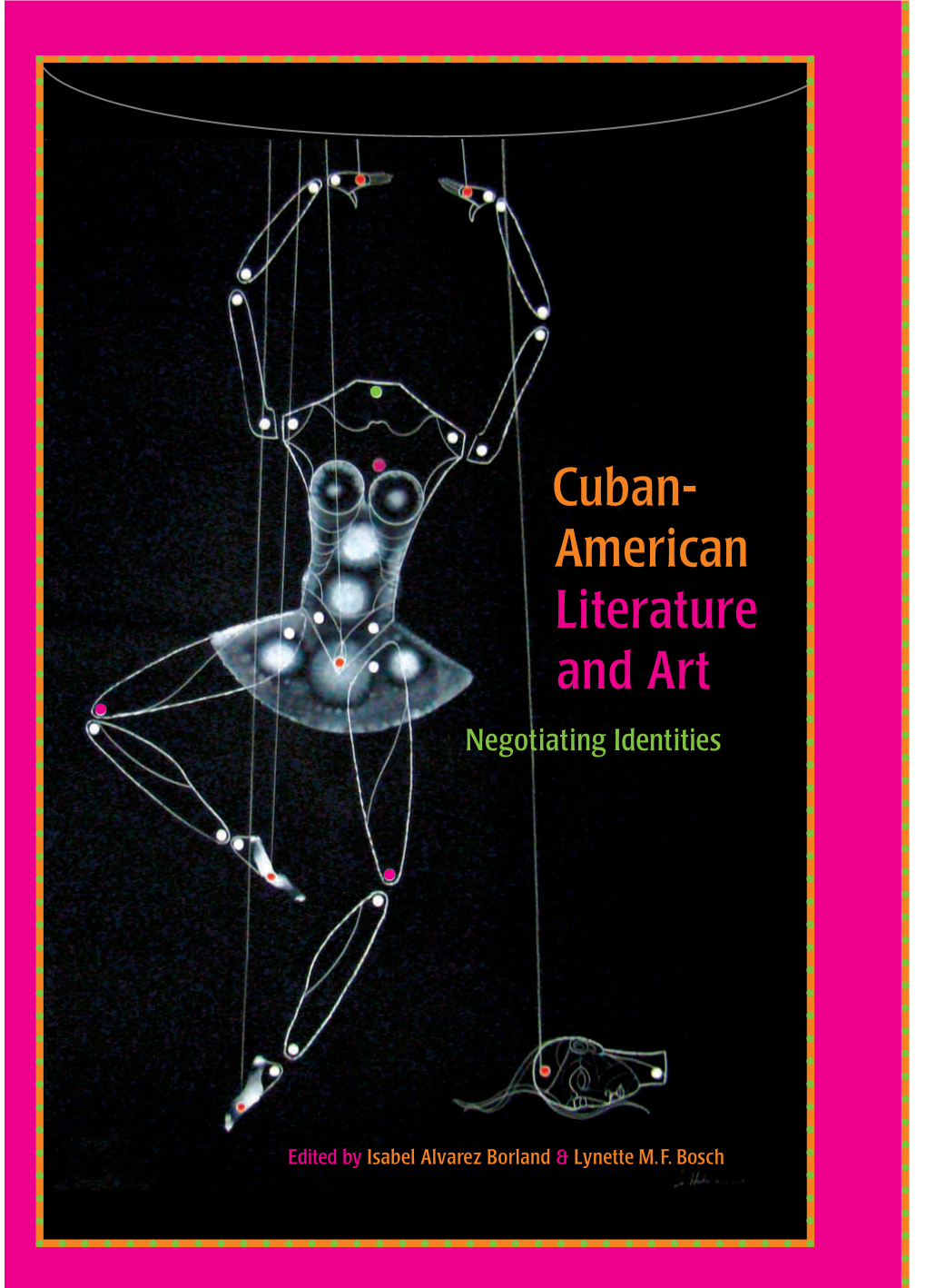

Cuban- American Literature and Art Negotiating Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Art Exhibition of Cuban Art

Diálogo Volume 7 Number 1 Article 13 2003 Endurance on the Looking Glass: an Art Exhibition of Cuban Art Egberto Almenas-Rosa Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Almenas-Rosa, Egberto (2003) "Endurance on the Looking Glass: an Art Exhibition of Cuban Art," Diálogo: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol7/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Latino Research at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diálogo by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Endurance on the Looking Glass: an Art Exhibition of Cuban Art Cover Page Footnote This article is from an earlier iteration of Diálogo which had the subtitle "A Bilingual Journal." The publication is now titled "Diálogo: An Interdisciplinary Studies Journal." This article is available in Diálogo: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol7/iss1/13 ENDURANCE ON THE LOOKING GLASS: AN ART EXHIBITION OF CUBAN ART by Egberto Almenas-Rosa “The unknown is almost our only tradition” -José Lezama Lima In the late 60s the noted Cuban author Gabriel Cabrera colonial outpost soon troubled by invasions, piracy, Infante squalled a most revealing pun when an brigandage, illegal trade, misgovernment, and the interviewer asked him why all the people from the internecine grudges that emanated from the Caribbean look alike. "It is not that all the Caribbean long-stretched institutions of servitude, this type of unity people look alike," he said; "it is that all the Caribbean came in handy. -

Artists, Aesthetics, and Migrations: Contemporary Visual Arts and Caribbean Diaspora in Miami, Florida by Lara C. Stein Pardo A

Artists, Aesthetics, and Migrations: Contemporary Visual Arts and Caribbean Diaspora in Miami, Florida by Lara C. Stein Pardo A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Ruth Behar, Chair Assistant Professor Nathan Daniel Beau Connolly, Johns Hopkins University Professor Tom Fricke Emeritus Professor Conrad P. Kottak Associate Professor Damani James Partridge © Lara Stein Pardo __________________________________ All Rights Reserved 2013 Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the institutional support that made it possible for me to research and write for extended periods of time over several years, and also confirmed the necessity of this research. Thank you. This research was supported through funding from the CIC/Smithsonian Institution Fellowship, the Cuban Heritage Collection Graduate Fellowship funded by the Goizueta Foundation, Rackham Merit Fellowship, Rackham Graduate School, Anthropology Department at the University of Michigan, Arts of Citizenship at the University of Michigan, Center for the Education of Women, Institute for Research on Women and Gender, and the Susan Lipschutz Fund for Women Graduate Students. I also thank the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Miami for hosting me as a Visiting Researcher during my fieldwork. There are many people I would like to acknowledge for their support of my work in general and this project in particular. Elisa Facio at the University of Colorado was the first person to suggest that I should consider working toward a PhD. Thank you. Her dedication to students goes above and beyond the role of a professor; you will always be Profesora to me. -

George Steiner> Octavio Paz José Emilio Pacheco

Octavio Paz CENTENARIO Adolfo Castañón • Paul-Henri Giraud José Emilio Pacheco 1939-2014 Literal. Latin American Voices • vol. 35 • winter / invierno, 2014 • Literal. Voces latinoamericanas • vol. 35 winter / invierno, 2014 • Literal. Voces Literal. Latin American Voices On Science and the Humanities George Steiner4 ¿Las humanidades, humanizan? Mario Bellatin4La aventura de Antonioni Fernando La Rosa4Archeological Photography Dossier Cuba: Maarten van Delden • Yvon Grenier • Héctor Manjarrez Carlos Espinosa • Mabel Cuesta • Ernesto Hernández Busto Forros L35.indd 1 07/02/14 10:24 d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y latin american voices d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y www.literalmagazine.com d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y d i v e r s i d a d / l i t e r a l / d i v e r s i t y 2 LITERAL. -

Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the Fashioning of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 1-7-2020 Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the Fashioning of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities Jeffrey Braytenbah Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Braytenbah, Jeffrey, "Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the ashioningF of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5356. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7229 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the Fashioning of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities by Jeff Braytenbah A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Kenneth J. Ruoff, Chair Laura Robson Jennifer Tappan Portland State University 2019 © 2019 Jeff Braytenbah Abstract Japan’s colonial activities on the island of Hokkaido were instrumental to the creation of modern Japanese national identity. Within this construction, the indigenous Ainu people came to be seen in dialectical opposition to the 'modern' and 'civilized' identity that Japanese colonial actors fashioned for themselves. This process was articulated through travel literature, ethnographic portraiture, and discourse in scientific racism which racialized perceived divisions between the Ainu and Japanese and contributed to the unmaking of the Ainu homeland: Ainu Mosir. -

Handmade and Mind Made Our Permanent Collection

Handmade And Mind Made Our Permanent Collection Raleigh-Durham International Airport Ellen Driscoll’s Wingspun, © 2008; Terminal 2, Raleigh-Durham International Airport Ed Carpenter’s Triplet, © 2010; Terminal 2, Raleigh-Durham International Airport About The Collection Raleigh-Durham International Airport is the gateway to Central and Eastern North Carolina. More than 9 million passengers travel through our airport each year on commercial flights, with millions more arriving daily to greet or dropoff passengers, fly on private aircraft or rent facilities for events. The Airport Authority created its Art Master Plan in 2000 to serve as an organizational tool for public art at RDU. The themes handmade and mind made were selected to refer to the region’s rich history of craftsmanship in furniture and textiles and the high-tech scientific reputation enjoyed today. An art advisory council comprised of Airport Authority staff, regional arts council representatives and others jury-selected the 15 pieces in RDU’s permanent collection to represent the collection’s theme and enhance the passenger experience. The collection’s first installation, The Terminal 1 Art Murals, was installed in 2002. The newest pieces will be installed in early 2014 as part of the Terminal 1 modernization project. Wellington Reiter Skilled in pen and ink drawings, as well as large scale architectural works, Wellington Reiter is a 1981 graduate of Tulane University and went on to study at Harvard University and the North London Polytechnic School. He is known for public commissions using steel and light. His pieces are on display at locations as varied as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Tulane University School of Architecture, offices of World Cinema Corporation in California and in private collections around the world. -

Cintas Foundation Entrusts Miami Dade College with Renowned Art Collection

Cintas Foundation Entrusts Miami Dade College with Renowned Art Collection Miami, June 20, 2011 - At a signing ceremony today, Miami Dade College(MDC) formally welcomed the renownedCintas Fellows Collection, the largest collection anywhere of Cuban art outside of Cuba. On an extended loan to MDC by the Cintas Foundation, the collection is comprised of nearly 300 pieces by artists of Cuban descent who have received prestigious Cintas Fellowships, awarded since 1963. More than 200 artists are represented in the collection through a wide variety of media including paintings, prints, photographs, drawings, films, sculptures and installation art. The vast scope of the collection reflects the heterogeneous nature of the artistic production of Cuban artists, spanning across various generations, and their significant aesthetic and historical contribution to modern and contemporary art. “We are so thrilled and proud to have the Cintas Fellows Collection here at MDC,” said MDC President Eduardo J. Padrón. Joining MDC President Dr. Eduardo J. Padrón and Cintas Foundation President Hortensia Sampedro are (L toR): MDC Foundation Chair Miguel G. Farra and Cintas Selections from the Cintas Fellows Collection will be on permanent display to Foundation board members Manuel Gonzalez, Maria the public for the first time at MDC’s National Historic Landmark Freedom Elena Prio, Margarita Cano and Rafael Miyar. Tower. “By exhibiting the works at the Freedom Tower, MDC is giving a voice to the remarkable artists in the collection,” said Cintas Foundation President Hortensia Sampedro. In addition to being the steward of this exceptional collection, MDC will also oversee the Cintas Foundation Fellowship Awards and host the annual awards exhibition and reception, an honor that played an influential role in the development and advancement of many artists’ careers. -

On the Craft of Fiction—EL Doctorow at 80

Interview Focus Interview VOLUME 29 | NUMBER 1 | FALL 2012 | $10.00 Deriving from the German weben—to weave—weber translates into the literal and figurative “weaver” of textiles and texts. Weber (the word is the same in singular and plural) are the artisans of textures and discourse, the artists of the beautiful fabricating the warp and weft of language into everchanging pattterns. Weber, the journal, understands itself as a tapestry of verbal and visual texts, a weave made from the threads of words and images. This issue of Weber - The Contemporary West spotlights three long-standing themes (and forms) of interest to many of our readers: fiction, water, and poetry. If our interviews, texts, and artwork, as always, speak for themselves, the observations below might serve as an appropriate opener for some of the deeper resonances that bind these contributions. THE NOVEL We live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind -- mass merchandising, advertising, politics conducted as a branch of advertising, the instant translation of science and technology into popular imagery, the increasing blurring and intermingling of identities within the realm of consumer goods, the preempting of any free or original imaginative response to experience by the television screen. We live inside an enormous novel. For the writer in particular it is less and less necessary for him to invent the fictional content of his novel. The fiction is already there. The writer’s task is to invent the reality. --- J. G. Ballard WATER Anything else you’re interested in is not going to happen if you can’t breathe the air and drink the water. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

The Oceania Cruises Art Collection

THE OCEANIA CRUISES ART CoLLECTION THE OCEANIA CRUISES ART CoLLECTION “I had the same vision and emotional connection in our art acquisitions as I did for Marina and Riviera themselves – to be beautiful, elegant, sophisticated and stylish. The ships and art are one.” – Frank Del Rio 2 | OCEANIA CRUISES ART COLLECTION Introduction In February of 2011, Oceania Cruises unveiled the cruise ship Marina at a gala ceremony in Miami. The elegant new ship represented a long list of firsts: the first ship that the line had built completely from scratch, the first cruise ship suites furnished entirely with the Ralph Lauren Home Collection, and the first custom-designed culinary studio at sea offering hands-on cooking classes. But, one of the most remarkable firsts caught many by surprise. As journalists, travel agents and the first guests explored the decks of the luxurious new vessel, they were astounded to discover that they had boarded a floating art museum, one that showcased a world-class collection of artworks personally curated by the founders of Oceania Cruises. Most cruise lines hire third party contractors to assemble the decorative art for their ships, selecting one of the few companies capable of securing a collection of this scale. The goal of most of these collections is, at best, to enhance the ambiance and, at worst, to simply match the decor. Oceania Cruises founders Frank Del Rio and Bob Binder wanted to take a different approach. “We weren’t just looking for background music,” Binder says. “We wanted pieces that were bold and interesting, pieces that made a statement, provoked conversation and inspired emotion.” Marina and her sister ship, Riviera, were designed to eschew the common look of a cruise ship or hotel. -

Martha Frayde Barraqué Papers (CHC5223)

University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Finding Aid - Martha Frayde Barraqué Papers (CHC5223) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Roberto C. Goizueta Pavilion 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-4900 Fax: (305) 284-4901 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/chc/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/chc5223 Martha Frayde Barraqué Papers Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Physical condition ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

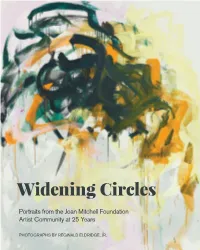

Widening Circles | Photographs by Reginald Eldridge, Jr

JOAN MITCHELL FOUNDATION MITCHELL JOAN WIDENING CIRCLES CIRCLES WIDENING | PHOTOGRAPHS REGINALD BY ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Sonya Kelliher-Combs Shervone Neckles Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles: Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years © 2018 Joan Mitchell Foundation Cover image: Joan Mitchell, Faded Air II, 1985 Oil on canvas, 102 x 102 in. (259.08 x 259.08 cm) Private collection, © Estate of Joan Mitchell Published on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name at the Joan Mitchell Foundation in New York, December 6, 2018–May 31, 2019 Catalog designed by Melissa Dean, edited by Jenny Gill, with production support by Janice Teran All photos © 2018 Reginald Eldridge, Jr., excluding pages 5 and 7 All artwork pictured is © of the artist Andrea Chung I live my life in widening circles that reach out across the world. I may not complete this last one but I give myself to it. – RAINER MARIA RILKE Throughout her life, poetry was an important source of inspiration and solace to Joan Mitchell. Her mother was a poet, as were many close friends. We know from well-worn books in Mitchell’s library that Rilke was a favorite. Looking at the artist portraits and stories that follow in this book, we at the Foundation also turned to Rilke, a poet known for his letters of advice to a young artist. -

A Finding Aid to the Giulio V. Blanc Papers, 1920-1995, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Giulio V. Blanc Papers, 1920-1995, in the Archives of American Art Rosa M. Fernández September 2001 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 4 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 6 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 6 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 8 Series 1: Biographical Files, 1994-1995, undated................................................... 8 Series 2: Miscellaneous Letters, 1983-1995, undated............................................. 9 Series 3: Artist Files, 1920-1995, undated............................................................. 10 Series 4: Exhibition Files, 1977-1995, undated....................................................