Open Banking: How to Design for Financial Inclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATP World Tour 2019

ATP World Tour 2019 Note: Grand Slams are listed in red and bold text. STARTING DATE TOURNAMENT SURFACE VENUE 31 December Hopman Cup Hard Perth, Australia Qatar Open Hard Doha, Qatar Maharashtra Open Hard Pune, India Brisbane International Hard Brisbane, Australia 7 January Auckland Open Hard Auckland, New Zealand Sydney International Hard Sydney, Australia 14 January Australian Open Hard Melbourne, Australia 28 January Davis Cup First Round Hard - 4 February Open Sud de France Hard Montpellier, France Sofia Open Hard Sofia, Bulgaria Ecuador Open Clay Quito, Ecuador 11 February Rotterdam Open Hard Rotterdam, Netherlands New York Open Hard Uniondale, United States Argentina Open Clay Buenos Aires, Argentina 18 February Rio Open Clay Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Open 13 Hard Marseille, France Delray Beach Open Hard Delray Beach, USA 25 February Dubai Tennis Championships Hard Dubai, UAE Mexican Open Hard Acapulco, Mexico Brasil Open Clay Sao Paulo, Brazil 4 March Indian Wells Masters Hard Indian Wells, United States 18 March Miami Open Hard Miami, USA 1 April Davis Cup Quarterfinals - - 8 April U.S. Men's Clay Court Championships Clay Houston, USA Grand Prix Hassan II Clay Marrakesh, Morocco 15 April Monte-Carlo Masters Clay Monte Carlo, Monaco 22 April Barcelona Open Clay Barcelona, Spain Hungarian Open Clay Budapest, Hungary 29 April Estoril Open Clay Estoril, Portugal Bavarian International Tennis Clay Munich, Germany Championships 6 May Madrid Open Clay Madrid, Spain 13 May Italian Open Clay Rome, Italy 20 May Geneva Open Clay Geneva, Switzerland -

Selling Mexico: Race, Gender, and American Influence in Cancún, 1970-2000

© Copyright by Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 ii SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _________________________ Tracy A. Butler APPROVED: _________________________ Thomas F. O’Brien Ph.D. Committee Chair _________________________ John Mason Hart, Ph.D. _________________________ Susan Kellogg, Ph.D. _________________________ Jason Ruiz, Ph.D. American Studies, University of Notre Dame _________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics iii SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 iv ABSTRACT Selling Mexico highlights the importance of Cancún, Mexico‘s top international tourism resort, in modern Mexican history. It promotes a deeper understanding of Mexico‘s social, economic, and cultural history in the late twentieth century. In particular, this study focuses on the rise of mass middle-class tourism American tourism to Mexico between 1970 and 2000. It closely examines Cancún‘s central role in buttressing Mexico to its status as a regional tourism pioneer in the latter half of the twentieth century. More broadly, it also illuminates Mexico‘s leadership in tourism among countries in the Global South. -

Current Affaires September 2013. Useful for IBPS CWE PO 2013 and IBPS CWE Clerk 2013 Exams

Current Affaires September 2013. Useful for IBPS CWE PO 2013 and IBPS CWE Clerk 2013 exams: The first Britisher to perform a space walk, who retired from NASA in the second week of August 2013- Colin Michael Foale Name of the largest blast furnace of India which was operationalised by SAIL on 10 August 2013- Durga Female tennis player to win The Rogers Cup 2013 and capture her 54th WTA singles title- Serena Williams Technology used by the researchers to find that autism affected the brains of males and females in a different way- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Name the captain of the 18-member hockey squad of India in the Asia Cup hockey tournament 2013- Sardar Singh Date on which International Lefthanders Day is celebrated across the world- 13 August Name of the First Twitter Hotel opened in Spain by the Melia brand of hotels-Social Wave House Name of the oldest Penguin who on 12 August 2013 turned 36 years old- King Penguin Missy Body which proposed first season of the Indian Badminton League (IBL)-Badminton Association of India (BAI) Name of the host country of 7th Asian Junior Wushu Championships- Philippines Name the fossil of the oldest known ancestor of modern rats recently unearthed in China- Rugosodon eurasiaticus Name of one of the most endangered bird species of the world that made a comeback in the US- Puerto Rican parrot Place at which The Travel & Tourism Fair (TTF) 2013, the biggest travel trade show of India started- Ahmadabad, Gujarat The former Prime Minister of Nepal who died on 15 August 2013 after battling with lung cancer- Marich Man Singh Shrestha Name the person who was termed as the Beast of Ukraine. -

Paradise Found?

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Anthropology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-15-2017 Paradise Found? Local Cosmopolitanism, Lifestyle Migrant Emplacement, and Imaginaries of Sustainable Development in La Manzanilla del Mar, Mexico Jennifer Cardinal University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Cardinal, Jennifer. "Paradise Found? Local Cosmopolitanism, Lifestyle Migrant Emplacement, and Imaginaries of Sustainable Development in La Manzanilla del Mar, Mexico." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jennifer Cardinal Candidate Anthropology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Ronda Brulotte, Chairperson Dr. Les Field Dr. David Dinwoodie Dr. Roberto Ibarra i Paradise Found? Local Cosmopolitanism, Lifestyle Migrant Emplacement, and Imaginaries of Sustainable Development in La Manzanilla del Mar, Mexico by JENNIFER CARDINAL B.A., Anthropology, University of Kansas, 2004 M.A., Anthropology, University of New Mexico, 2009 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anthropology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2017 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who played a role in this dissertation, including those who participated in and funded research, those who provided support and guidance during the writing process, and those who generally made things cool during the years of researching and writing. -

Smarter Crowdsourcing for Anti-Corruption a Handbook of Innovative Legal, Technical, and Policy Proposals and a Guide to Their Implementation

SMARTER CROWDSOURCING ANTI-CORRUPTION Smarter Crowdsourcing for Anti-corruption A Handbook of Innovative Legal, Technical, and Policy Proposals and a Guide to their Implementation Beth Simone Noveck Kaitlin Koga Rafael Aceves Garcia Hannah Deleanu Dinorah Cantú-Pedraza APRIL 2018 anticorruption.smartercrowdsourcing.org SMARTER CROWDSOURCING anticorruption.smartercrowdsourcing.org ANTI-CORRUPTION Acknowledgments We acknowledge the contribution to the execution of this project to the following individuals from the Inter- American Development Bank (IDB): ‣ Nicolás Dassen, Senior Specialist, Modernization of the Public Sector (ICS/IFD) ‣ Arturo Muente, Senior Specialist, Modernization of the Public Sector (ICS/IFD) ‣ Mario Sanginés, Principal Specialist in Mexico, Modernization of the Public Sector (ICS/IFD) ‣ Darinka Vásquez Jordan, Consultant, Innovation in Citizen Services (ICS/IFD) ‣ Michelle Marshall, Consultant, Knowledge Management and Open Innovation (KNM/KNL) Copyright © 2018 Inter-American Development Bank (“IDB”). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons IGO 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license (CC-IGO 3.0 BY-NC-SA) (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode) and may be reproduced with attribution to the IDB and for any non-commercial purpose in its original or in any derivative form, provided that the derivative work is licensed under the same terms as the original. The IDB is not liable for any errors or omissions contained in derivative works and does not guarantee that such derivative works will not infringe the rights of third parties. Any dispute related to the use of the works of the IDB that cannot be settled amicably shall be submitted to arbitration pursuant to the UNCITRAL rules. -

Mexico and Mexican Communities in the United States

The Melting Borde r Mexico and Mexican Comm unities in the United Sta t e s by Robert S.Leiken Center for Equal Opportunity The Melting Borde r Mexico and Mexican Comm unities in the United Sta t e s Robert S.Leiken Center for Equal Opportunity ©2000 by the Center for Equal Opportunity, Washington, D.C. Table of Cont e n t s EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 CHAPTER ONE: A BACKGROUND OF CHANGE 6 Acercamiento:Getting Closer / Page 6 The Mexican Populations in the U.S. / Page 7 Developments on the U.S.Side / Page 8 Developments on the Mexican Side / Page 8 CHAPTER TWO: THE PROGRAM FOR MEXICAN COMMUNITIES ABROAD (PCME) 9 1990:The Initiative of the Mexican Government / Page 9 Current Structure and Activities of the PCME / Page 10 CHAPTER THREE: HOMETOWN ASSOCIATIONS (HTAs) 11 Origins / Page 11 Number,Size, and Composition / Page 12 The Role of the Mexican Consulates in the Formation of HTAs / Page 13 Rural Derivation / Page 14 Historical Precedents / Page 14 Purposes and Activities / Page 15 Local, State, and National Ties:The Federation of HTAs / Page 17 The Impact of HTAs on Governance and Politics in Mexico / Page 18 The Automobile Deposit Affair / Page 20 Future Prospects / Page 21 The American Character of the HTAs / Page 21 HTA Citizenship Promotion and Political Participation in the Host Country / Page 22 Educational Efforts of the HTAs / Page 23 CHAPTER FOUR: EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES 24 Historical Background / Page 24 Bilingual Education / Page 25 Immersion Courses for Bilingual Teachers in the U.S. and Teacher Exchange Programs / Page 26 Adult Education -

2011 San Antonio Meeting

Western Political Science Association CONFERENCE THEME: TRANSNATIONAL BORDERS, EQUITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE April 21 – 23, 2011 San Antonio, Texas TABLE OF CONTENTS Page WELCOME AND SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................ ii WESTERN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION OFFICERS .................. v COMMITTEES OF THE WESTERN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION ..................................................................................... vii WPSA ANNUAL AWARDS GUIDELINES ................................................... ix WPSA AWARDS TO BE ANNOUNCED AT THE 2011 MEETING ............. xi CALL FOR PAPERS 2012 MEETING ........................................................ xii MEETING SCHEDULE AND SPECIAL EVENTS ........................................ 1 SCHEDULE OF PANELS ............................................................................ 4 PANEL LISTINGS: THURSDAY, 8:00 AM – 9:45 AM .................................................. 33 THURSDAY, 10:00 AM – 11:45 AM .................................................. 41 THURSDAY, 1:15 PM – 3:00 PM .................................................. 51 THURSDAY, 3:15 PM – 5:00 PM .................................................. 62 FRIDAY, 8:00 AM – 9:45 AM ................................................. 73 FRIDAY, 10:00 AM – 11:45 AM ................................................. 84 FRIDAY, 1:15 PM – 3:00 PM ................................................. 94 FRIDAY, 3:15 PM – 5:00 PM ............................................... 106 SATURDAY, 8:00 AM – 9:45 PM -

Dekalb Agresearch Dekalb, Illinois

Inventory of the DeKalb AgResearch DeKalb, Illinois Collection In the Regional History Center RC 190 1 INTRODUCTION Leo Olson, Communications Director for DeKalb Genetics, donated the company's records to the Northern Illinois Regional History Center throughout 1980 and continued to donate additions until July 1988. An addendum was added in March 2001 by Monsanto through the DeKalb Alumni Group. Property rights in the collection belong to the Regional History Center; literary rights are dedicated to the public. There are no restrictions on access to the collection. Twenty- four hours advanced notice is requested for the audio-visual material due to the need of special equipment. Linear feet of shelf space: 196 l.f. Number of containers: 428 + 2 volumes Northern Illinois Regional History Center Collection 190 SCOPE AND CONTENT This collection contains many of the records generated by the DeKalb Genetics Corporation. The materials, dating from 1910-2011, provide information for a basic history of the company; for ascertaining the role played by the industry in the DeKalb area, the United States, and around the world; for the research in the company's areas of expertise; and for analyzing marketing techniques and approaches. The collection is organized into 10 series: Historical Research and General Corporate Records, Sales and Production, Research, Publications, Subject Files, Subsidiaries, Charlie Gunn, Dave Wagley, Rubendall, and Audio-visuals. While most of the collection is in English, there is material in various languages. The Historical Research and General Corporate Records series (I) is divided into two subseries. The Historical Research subseries consists of histories, historical research, and merger information from DeKalb Genetics subsidiaries. -

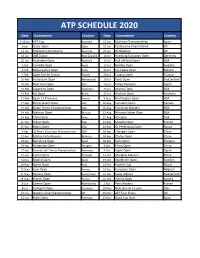

Atp Schedule 2020

ATP SCHEDULE 2020 Date Tournament Country Date Tournament Country 3-12-Jan ATP Cup Australia 22-Jun Mallorca Championships Spain 6-Jan Qatar Open Qatar 22-Jun Eastbourne International UK 13-Jan Adelaide International Australia 29-Jun Wimbledon UK 13-Jan ASB Classic New Zealand 13-Jul Hamburg European Open Germany 20-Jan Australian Open Australia 13-Jul Hall of Fame Open USA 3-Feb Cordoba Open Spain 13-Jul Nordea Open Sweden 3-Feb Maharashtra Open India 20-Jul Los Cabos Open Mexico 3-Feb Open Sud de France France 20-Jul Croatia Open Croatia 10-Feb Rotterdam Open Netherlands 20-Jul Swiss Open Switzerland 10-Feb New York Open USA 25-Jul Tokyo Olympics Japan 10-Feb Argentina Open Argentina 27-Jul Atlanta Open USA 16-Feb Rio Open Brazil 27-Jul Austrian Open Australia 17-Feb Open 13 Provence France 2-Aug Washington Open USA 17-Feb Delray Beach Open USA 10-Aug Canadian Open Canada 24-Feb Dubai Tennis Championships UAE 16-Aug Cincinnati Masters USA 24-Feb Mexican Open Mexico 23-Aug Winston-Salem Open USA 24-Feb Chile Open Chile 31-Aug US Open USA 12-Mar Indian Wells USA 21-Sep Moselle Open France 25-Mar Miami Open USA 21-Sep St. Petersburg Open Russia 6-Apr US Men's Clay Court Championships USA 28-Sep Chengdu Open China 12-Apr Monte Carlo Masters Monaco 28-Sep Zhuhai Open China 20-Apr Barcelona Open Spain 28-Sep Sofia Open Bulgaria 20-Apr Hungarian Open Hungary 5-Oct China Open China 27-Apr Bavarian Int'l Tennis Championships Germany 5-Oct Japan Open Japan 27-Apr Estoril Open Portugal 11-Oct Shanghai Masters China 3-May Madrid Open Spain 19-Oct Stockholm Open Sweden 10-May Italian Open Italy 19-Oct Kremlin Cup Russia 17-May Lyon Open France 19-Oct European Open Belgium 17-May Geneva Open Switzerland 26-Oct Swiss Indoors Switzerland 24-May French Open France 26-Oct Vienna Open Austria 8-Jun Libema Open Netherlands 2-Nov Paris Masters France 8-Jun Stuttgart Open Germany 10-Nov Next Gen ATP Finals Italy 15-Jun Queen's Club Championships UK 15-Nov ATP Tour Finals UK 15-Jun Halle Open Germany 23-Nov Davis Cup final Spain. -

Sixteenth-Century Mexican Architecture Monika Brenišínová

Sixteenth-century Mexican Architecture Monika Brenišínová To cite this version: Monika Brenišínová. Sixteenth-century Mexican Architecture: Transmission of Forms and Ideas be- tween the Old and the New World. Historie, otázky, problémy, Faculty of Arts, Charles University, 2016, pp.9-24. halshs-01534717 HAL Id: halshs-01534717 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01534717 Submitted on 8 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Sixteenth-century Mexican Architecture: Transmission of Forms and Ideas OPEN ACCESS between the Old and the New World* Monika Brenišínová This article deals with the subject of 16th century Mexican monastic architecture and its artistic em- bellishments. Its aim is to present the architecture and its decoration program within an appropriate historical context, putting a particular emphasis on the process of cultural transmission and sub- sequent changes between the Old and the New World. Some attention is also paid to the European art of the modern age with regard to the discovery of America and its impact on the western world- view (imago mundi). The article concludes that the Mexican culture represents an example of a very successful and vivid translation of Western culture (translatio studii) towards the America, albeit it stresses that the process of cultural transmission was reciprocal. -

HORIZONS of the WESTERN SADDLE 4 Richard E

MAN MADE MOBILE Early Saddles of Western North America <. HSKIS^ Richard E. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given sub stantive review. -

Games & Sports

IMPORTANT MCQ SESSION ON: GAMES & SPORTS CURRENT AFFAIRS 2020 instagram.com/knowvation1 [email protected] fb.com/knowvation twitter.com/knowvation1 knowvation.in Which of the following teams won the Indian Premier League (IPL) 2020? A. Chennai Super Kings B. Delhi Capitals C. Mumbai Indians D. Rajasthan Royals Points to Know (PTN): Orange Cap winner: KL Rahul (670 runs) Purple Cap winner: Kasigo Rabada (29 wickets) Who among the following Indian boxers won gold medal at the recently concluded Alexis Valentine International Boxing Tournament? A. Amit Phangal B. Sanjeet C. Ashish Kumar D. All of these Sources: loksatta.com PTN: The tournament was held at Nantes, France. Kavinder Singh Bisht, the boxer in the 57 kg weight category claimed the silver medal. In Badminton, who won the men’s single title in the Denmark Open 2020? A. Chris Langridge B. Anders Antonsen C. Rasmus Gemke Sources: wimbledonclub.co.uk D. Mark Lamsfuss PTN: World number seven Anders Antonsen of Denmark defeated his compatriot Rasmus Gemke. Nozomi Okuhara of Japan clinched the Denmark Open 2020 title beating three-time world champion Carolina Marin. Which of the following teams won the NBA Championship 2020? A. Los Angeles Lakers B. Miami Heat C. Boston Celtics D. Toronto Raptors PTN: LA Lakers crushed Miami Heat to win a record-equaling 17th NBA championship with Boston Celtics. LeBron James was adjudged the MVP for the NBA Finals for the fourth time. Name the Indian shuttler who has been roped in as the brand ambassador of India's first-ever badminton brand 'Transform'? A. Srikanth Kidambi B.