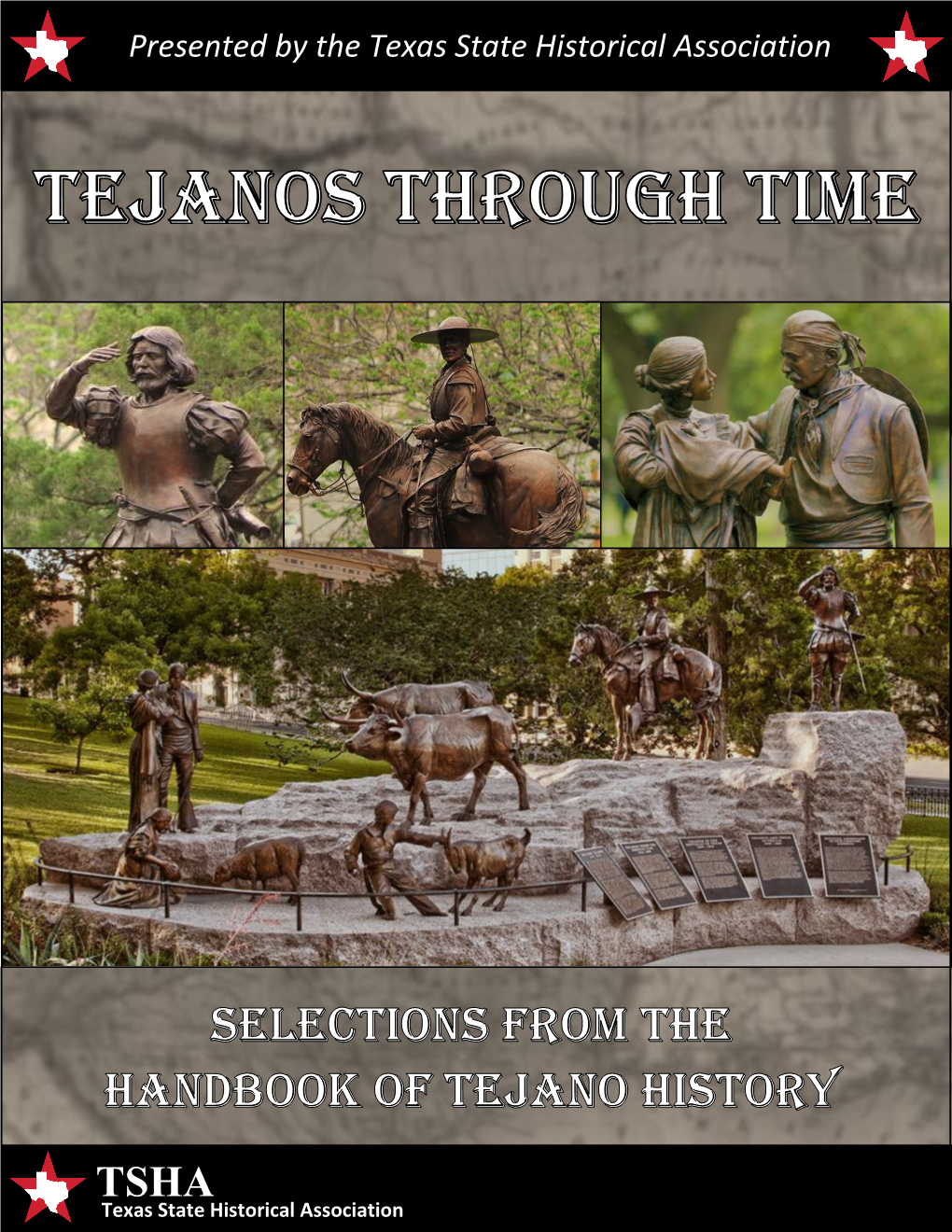

Presented by the Texas State Historical Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME Chicano Studies Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 119 923 ric 009 066 AUTHOR Marquez, Benjamin, Ed. TITLE Chicano Studies Bibliography: A Guide to the Resources of the Library at the University of Texas at El Paso, Fourth Edition. INSTITUTION Texas Univ., El Paso. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 138p.; For related document, see ED 081 524 AVAILABLE PROM Chicano Library Services, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79902 ($3.00; 25% discount on 5 or more copies) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$7.35 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Audiovisual Aids; *Bibliographies; Books; Films; *library Collections; *Mexican Americans; Periodicals; *Reference Materials; *University Libraries IDENTIFIERS Chicanos; *University of Texas El Paso ABSTRACT Intended as a guide to select items, this bibliography cites approximately 668 books and periodical articles published between 1925 and 1975. Compiled to facilitate research in the field of Chicano Studies, the entries are part of the Chicano Materials Collection at the University of Texas at El Paso. Arranged alphabetically by the author's or editor's last name or by title when no author or editor is available, the entries include general bibliographic information and the call number for books and volume number and date for periodicals. Some entries also include a short abstract. Subject and title indices are provided. The bibliography also cites 14 Chicano magazines and newspapers, 27 audiovisual materials, 56 tape holdings, 10 researc°1 aids and services, and 22 Chicano bibliographies. (NQ) ******************************************14*************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. -

Examining the Lives of Five Mexican American Female

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository EXAMINING THE LIVES OF FIVE MEXICAN AMERICAN FEMALE EDUCATORS WITH MORE THAN 25 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE IN SOUTH TEXAS BORDER SCHOOLS A Dissertation by GEORGEANNE RAMON-REUTHINGER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2005 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction © 2005 GEORGEANNE RAMON-REUTHINGER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED EXAMINING THE LIVES OF FIVE MEXICAN AMERICAN FEMALE EDUCATORS WITH MORE THAN 25 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE IN SOUTH TEXAS BORDER SCHOOLS A Dissertation by GEORGEANNE RAMON-REUTHINGER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Patricia J. Larke Committee Members, Norvella P. Carter Juan Lira Salvador Hector Ochoa Head of Department, Dennie L. Smith December 2005 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction iii ABSTRACT Examining the Lives of Five Mexican American Female Educators With More Than 25 Years of Experience in South Texas Border Schools. (December 2005) GeorgeAnne Ramon-Reuthinger, B.S., Texas A&I University; M.Ed., Texas A&I University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Patricia J. Larke This study was a qualitative study that explored the lives of Mexican American female educators with more than 25 years of experience teaching in South Texas border schools. The purpose of the study was to explore the participants’ views and perceptions regarding their educational experiences, both formal and informal, within the contexts of community, political climate, family, religious, and educational institutions. -

Siete Lenguas: the Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2016 Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Beagle, Christine. "Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/34 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Garcia i Christine Beagle Candidate English, Rhetoric and Writing Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Michelle Hall Kells, Chairperson Irene Vasquez Natasha Jones Melina Vizcaino-Aleman Garcia ii SIETE LENGUAS: THE RHETORICAL HISTORY OF DOLORES HUERTA AND THE RISE OF CHICANA RHETORIC by CHRISTINE BEAGLE B.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2005 M.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico November 10, 2015 Garcia iii DEDICATION To my children Brandon, Aliyah, and Eric. Your brave and resilient love is my savior. I love you all. Garcia iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, to my dissertation committee Michelle Hall Kells, Irene Vasquez, Natasha Jones, and Melina Vizcaino-Aleman for the inspiration and guidance in helping this dissertation project come to fruition. -

NORMA Ella CANTÚ Professor Emerita, University of Texas, San

NORMA ELlA CANTÚ Professor Emerita, University of Texas, San Antonio Professor of Latina/o Studies and English, University of Missouri, Kansas City Web page : http://colfa.utsa.edu/English/cantu.html Blog: www.wordpress.normacantu.com Office Address : Home Address : E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Telephone : Haag Hall 204 G 5643 Locust St Office : 816-235-4125 5120 Rockhill Road Kansas City, MO 65110 Cell : 210-363-4736 Kansas City, MO 64113 Education/Certification 1984 Secondary English and Government Certification by the State of Texas 1982 Ph.D. University of Nebraska—Lincoln Co-Chairs: Profs. Paul Olson and Ralph Grajeda Dissertation: The Offering and the Offerers: A Generic Illocation of a Laredo Pastorela in the Tradition of the Shepherds’ Plays 1976 M.S. Texas A&I University--Kingsville, with honors Major: English Minor: Political Science 1973 B.S. Texas A&I University--Laredo, cum laude Major: Education: English/Political Science 1970 A.A. Laredo Junior College Areas of Teaching and Research Interest Latino/a Studies, Chicano/a Literature, Border Studies, Folklore, Women Studies, Cultural Studies, Creative Writing Teaching Experience 2013-Present University of Missouri, Kansas City—Full Professor of Latina/o Studies 2012-Present University of Texas, San Antonio—Professor Emerita 2000-2012 University of Texas, San Antonio—Full Professor of Latina/o Literatures 1993-2000 Texas A&M International University—Full Professor 1994-1995 Georgetown University--School for Continuing Education—Visiting Professor, Literature -

FARMWORKER JUSTICE MOVEMENTS (4 Credits) Syllabus Winter 2019 Jan 07, 2019 - Mar 15, 2019

1 Ethnic Studies 357: FARMWORKER JUSTICE MOVEMENTS (4 credits) Syllabus Winter 2019 Jan 07, 2019 - Mar 15, 2019 Contact Information Instructors Office, Phone & Email Ronald L. Mize Office Hours: Wed 11:30-12:30, or by Associate Professor appointment School of Language, Culture and Society 541.737.6803 Office: 315 Waldo Hall Email [email protected] Class Meeting: Wednesdays, 4:00 pm - 7:50 pm, Learning Innovation Center (LINC) 360, including three off- campus service/experiential learning sessions. The course is four credits based on number of contact hours for lecture/discussion and three experiential learning sessions. Course Description: Justice movements for farmworkers have a long and storied past in the annals of US history. This course begins with the 1960s Chicano civil rights era struggles for social justice to present day. Focus on the varied strategies of five farmworker justice movements: United Farm Workers, Farm Labor Organizing Committee, Pineros y Campesinos Unidos Noroeste, Migrant Justice, and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. This course was co-designed with a founder of PCUN, Larry Kleinman, who actively co-leads the course as his schedule allows. The course is structured around the question of the movement and its various articulations. Together, we will cover some central themes and strategies that comprise the core of farm worker movements but the course is designed to allow you, the student, to explore other articulations you find personally relevant or of interest. This course is designated as meeting Difference, Power, and Discrimination requirements. Difference, Power, and Discrimination Courses Baccalaureate Core Requirement: ES357 “Farmworker Justice Movements” fulfills the Difference, Power, and Discrimination (DPD) requirement in the Baccalaureate Core. -

Latin Neighborhoods in the United States Ernesto Castañeda Assistant

Latin Neighborhoods in the United States Ernesto Castañeda Assistant Professor of Sociology American University, Washington DC MARCH 1, 2019 Abstract Inner-cities, African-American neighborhoods, Chinatowns and other abstract concepts of racialized spaces occupy important roles in social theory and policy, yet the concept of the Barrio, or Mexican-American neighborhood, has faded away since Oscar Lewis’ work on “the culture of poverty.” Is there a policy or theoretical use to talking about U.S. Barrios in general or should the discussion of Mexican neighborhoods be place-specific? The presentation compares two Latino neighborhoods: El Barrio/East Harlem, New York City, NY; and El Segundo Barrio, El Paso, TX. Levels of Analysis Demographers use Census data and large surveys ◦ Good to look at trends in the size of the Latino population ◦ Macro Level Less common to look at ethnic groups beyond neighborhood boundaries and to compare between cities ◦ Good to look at particulars and generalizable processes ◦ Meso level Community Studies – look at particular neighborhoods ◦ Good to discover processes and social dynamics ◦ Micro Level (Castañeda et al. 2013) Chicago School Studied immigrants as communities in bounded urban areas. Urban Communities A theoretical, tourist, and mental map fetish? Research Questions Does it make sense to talk about a general Latino experience across the U.S.? Is there a policy or theoretical use to talking about U.S. Barrios in general or should the discussion of Mexican neighborhoods be place-specific? How do local contexts and built environments affect inter-ethnic relations? Barrios ❑ There is relatively small amount of academic work published about Barrios or Latino neighborhoods. -

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER 6-9 JoinJoin UsUs inin T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A CONTENTS N 3 Why Come to Austin? PRE-MEETING WORKSHOPS 37 AASLH Institutional A 6 About Austin 20 Wednesday, September 6 Partners and Patrons C I 9 Featured Speakers 39 Special Thanks SESSIONS AND PROGRAMS R 11 Top 12 Reasons to Visit Austin 40 Come Early and Stay Late 22 Thursday, September 7 E 12 Meeting Highlights and Sponsors 41 Hotel and Travel 28 Friday, September 8 M 14 Schedule at a Glance 43 Registration 34 Saturday, September 9 A 16 Tours 19 Special Events AUSTIN!AUSTIN! T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A N othing can replace the opportunitiesC ontents that arise A C when you intersect with people coming together I R around common goals and interests. E M A 2 AUSTIN 2017 oted by Forbes as #1 among America’s fastest growing cities in 2016, Austin is continually redefining itself. Home of the state capital, the heart of live music, and a center for technology and innovation, its iconic slogan, “Keep Austin Weird,” embraces the individualistic spirit of an incredible city in the hill country of Texas. In Austin you’ll experience the richness in diversity of people, histories, cultures, and communities, from earliest settlement thousands of years in the past to the present day — all instrumental in the growth of one of the most unique states in the country. -

May 14, 2016 Don Haskins Center Class of 2016

CLASS OF 2016 MAY 14, 2016 DON HASKINS CENTER THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO CLASS OF 2016 MAY 14, 2016 DON HASKINS CENTER TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Regents/Senior Administrative Officials 3 Morning Ceremony Program 4 Order of Academic Procession 5 Members of Faculty/Candidates for Degree 6 Recessional 7 Afternoon Ceremoniy Program 8 Order of Academic Procession 9 Members of Faculty/Candidates for Degree 10 Recessional 11 Evening Ceremony Program 12 Order of Academic Procession 13 Members of Faculty/Candidates for Degree 14 Recessional 15 TIME’s 100 Most Influential People 16 Distinguished Alumni 17 Candidates for Degrees College of Liberal Arts 22 College of Education 26 College of Business Administration 27 School of Nursing 29 College of Engineering 30 College of Science 31 College of Health Sciences 32 Graduate School 34 University Honors 41 Honors Candidates 42 Student Honors 46 Honors Regalia 49 Regalia 50 Men O’ Mines 57 Commencement Committee 59 BOARD OF REGENTS The University of Texas System Paul L. Foster, Chairman . El Paso R. Steven Hicks, Vice Chairman . Austin Jeffery D. Hildebrand, Vice Chairman . Houston Ernest Aliseda . McAllen David J. Beck . .Houston Alex M. Cranberg . Houston Wallace L. Hall, Jr. Dallas Brenda Pejovich. Dallas Sara Martinez Tucker. Dallas Justin A. Drake (Student Regent) . Galveston Francie A. Frederick General Counsel to the Board of Regents SENIOR ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICIALS The University of Texas System William H. McRaven Chancellor David E. Daniel, Ph.D. Deputy Chancellor Steven Leslie, Ph.D. Executive Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Raymond S. Greenberg, M.D., Ph.D. Executive Vice Chancellor for Health Affairs Scott C. -

PDF, Guide to Comisión Femenil Mexicana

University of California, Santa Barbara Davidson Library Department of Special Collections California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives GUIDE TO COMISIÓN FEMENIL MEXICANA NACIONAL ARCHIVES 1967-1997 [Bulk dates 1970-1990] Collection Number: CEMA 30. Size Collection: 31 linear feet (63 boxes). Acquisition Information: Donated by CFMN extant board of directors. Gift agreement dated January, 2001. Access restrictions: None. Use Restriction: Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. Processing Information: Project Director Salvador Güereña, principle processor Alexander Hauschild, assistant Michelle Welch, 2003. Location: Del Norte. M:\CEMA COLLECTIONS\CFMN\cfmn_guide.doc 1 HISTORY The Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional, Inc. was founded by resolution at the 1970 National Issues Conference in Sacramento California. The Founding President was Francisca Flores, a Chicana activist already well respected for her many decades of community works. Recognizing that there were few organizations that met the needs of Latina women, nine resolutions were presented to the full body calling for the establishment of a Chicana/Mexicana women's commission. The resolution called for a commission that could direct it’s efforts toward organizing and networking women that they might assume leadership positions within the Chicano movement and in the community. Designed to disseminate news and information regarding the achievements of Chicana/Mexican women, and promote programs that provide solutions for women and their families; the resolutions read as follows: RESOLUTION TO ESTABLISH COMISIÓN FEMENIL MEXICANA NACIONAL, INC. -

The Early Utilization and the Distribution of Agave in The

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository UNM Bulletins Scholarly Communication - Departments 1938 The ae rly utilization and the distribution of agave in the American southwest Edward Franklin Castetter Willis Harvey Bell Alvin Russell Grove Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/unm_bulletin Recommended Citation Castetter, Edward Franklin; Willis Harvey Bell; and Alvin Russell Grove. "The ae rly utilization and the distribution of agave in the American southwest." University of New Mexico biological series, v. 5, no. 4, University of New Mexico bulletin, whole no. 335, Ethnobiological studies in the American Southwest, 6 5, 4 (1938). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/unm_bulletin/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarly Communication - Departments at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNM Bulletins by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. hlliig4 The University olNewMexico Bulletin 1 Ethnobiolbgical Studies in the American SouthweSt VI. \The Early Utilization and the Diftribution ofAgave in the American Southweft EDWARD F. CASTETTER, WILLIS H. BELL and ALVIN R. GROVE • .~ ~ r v~r4..f.2.,,",,~- A , ,-' "W'/ I))j j'A1' WJl\( ;JJ;,£~/:(Jcu~~/ HI" I' ~~fi!:~~e . M>rX~;;fre~ UNIVERSITY OF NEW ...//f ':iT' 1938 . Price 50 cents .':.W\~) e.s<:-f1} Qr~: rvJrl The University of New Mexico Vl5 . ,r Bulletin ~('J I 'j"' Ethnobiological Studies In the American Southwest VI. The Early Uttlization and the Distribution ofAgave in the American Southrzvest By EDWARD F. CASTETTER WILLIS H. BELL ALVIN R. GROVE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO BULLETIN Whole Number 335 December 1, 1938 Biological Series, Vol. -

Cultural Landscape Study of Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2000 Cultural Landscape Study of Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas David Keith Myers University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Myers, David Keith, "Cultural Landscape Study of Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas" (2000). Theses (Historic Preservation). 398. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/398 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Myers, David Keith (2000). Cultural Landscape Study of Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/398 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Landscape Study of Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Myers, David Keith (2000). Cultural Landscape Study of Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/398 'M'- UNIVERSITY^ PENNSYLVANIA. LIBRARIES CULTURAL LANDSCAPE STUDY OF FORT DAVIS NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE, TEXAS David Keith Myers A THESIS Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2000 Supervisor Gustavo Araoz ^ j^ Lecturer in Historic Preservatfon 4V Ik^l^^ ' Graduate Group Chair Fra'triUlL-Matero Associate Professor in Architecture j);ss.)?o5 Zooo. -

Mexican American Resource Guide: Sources of Information Relating to the Mexican American Community in Austin and Travis County

MEXICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE: SOURCES OF INFORMATION RELATING TO THE MEXICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN AUSTIN AND TRAVIS COUNTY THE AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY Updated by Amanda Jasso Mexican American Community Archivist September 2017 Austin History Center- Mexican American Resource Guide – September 2017 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use so that customers can learn from the community’s collective memory. The collections of the AHC contain valuable materials about Austin and Travis County’s Mexican American communities. The materials in the resource guide are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This guide is one of a series of updates to the original 1977 version compiled by Austin History staff. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals, support groups and Austin History Center staff. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the Find It: Austin Public Library On-Line Library Catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing individual items in the collection with entries under author, title, and subject. These tools lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be very difficult to find. It must be noted that there are still significant gaps remaining in our collection in regards to the Mexican American community.