Re-Evaluating Democratic Revolutions, Nationalism and Organized Crime in Ukraine from a Comparative Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Ukraine Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE Paul Kubicek The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kubicek, Paul. The history of Ukraine / Paul Kubicek. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096 –2095) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 – 0 –313 – 34920 –1 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine —History. I. Title. DK508.51.K825 2008 947.7— dc22 2008026717 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by Paul Kubicek All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008026717 ISBN: 978– 0– 313 – 34920 –1 ISSN: 1096 –2905 First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48 –1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. -

'Krym Nash': an Analysis of Modern Russian Deception Warfare

‘Krym Nash’: An Analysis of Modern Russian Deception Warfare ‘De Krim is van ons’ Een analyse van hedendaagse Russische wijze van oorlogvoeren – inmenging door misleiding (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 16 december 2020 des middags te 12.45 uur door Albert Johan Hendrik Bouwmeester geboren op 25 mei 1962 te Enschede Promotoren: Prof. dr. B.G.J. de Graaff Prof. dr. P.A.L. Ducheine Dit proefschrift werd mede mogelijk gemaakt met financiële steun van het ministerie van Defensie. ii Table of contents Table of contents .................................................................................................. iii List of abbreviations ............................................................................................ vii Abbreviations and Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... vii Country codes .................................................................................................................................................... ix American State Codes ....................................................................................................................................... ix List of figures ...................................................................................................... -

Organized Economic Crime and Corruption in Ukraine

Document Title: Organized Economic Crime and Corruption in Ukraine Author(s): Alexander G. Kalman Document No.: 204374 Date Published: 2004 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this document available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the Department. Organized Economic Crime and Corruption in Ukraine Alexander G. Kalman Yaroslav Mudry National Law Academy of Ukraine One of the most disastrous consequences of the collapse of the Ukrainian communist system has been the wide-spread increase of economic crime. This phenomenon is self-sustaining, penetrating all levels of Ukraine’s economy and administrative sectors. Criminal activity helps to sustain the shadow economy in Ukraine, which has been estimated by various sources to constitute 50-60% of the economy. Law enforcement and administrative efforts have been largely futile in curbing this corruption. Nevertheless, it is possible to overcome the criminal social and economic order that has become ingrained in this “shadow economy.” This paper seeks to propose policy solutions for Ukrainian economic crime and corruption, that could be implemented at the national level. Present day organized crime and corruption in Ukraine, complex in both content and structure, are a direct result of the profound economic, cultural, and political changes brought about during Ukraine’s transition as a Newly Independent State. -

LEGEA ŞI VIAŢA СОДЕРЖАНИЕ Publicaţie Ştiinţifico-Practică ISSN 1810-309X Александр БАКУМОВ

LEGEA ŞI VIAŢA СОДЕРЖАНИЕ Publicaţie ştiinţifico-practică ISSN 1810-309X Александр БАКУМОВ. Проблема изменения правовых позиций Конституционного Суда Украины Întreprindere de stat в контексте обеспечения юридической Fondator – Agenția Proprietății Publice ответственности государства ................................................ 3 al Republicii Moldova Certificat de înregistrare Андрей БОРОВИК. О сущности и содержании nr. 10202264 din 11.02.1993 специально-криминологического предупреждения злостного неповиновения требованиям администрации Publicaţie acreditată de Consiliul учреждения исполнения наказаний ..................................... 9 Suprem pentru Ştiinţă şi Dezvoltare Tehnologică al Academiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei prin Анна ВИТЮК. Профессиональная этика судьи Hotărîrea nr. 169 din 21.12.2017 в контексте ограничения реализации судьями политических и гражданских прав человека ...................... 13 Revista este inclusă în baza științifică internațională Index Copernicus International (Republica Polonă) Артур ГИЛЬБУРТ. Закрепление политической системы в конституциях постсоветских государств .......................... 17 Categoria C Asociaţi: Curtea Constituţională, Curtea Supremă Карина ГНАТЕНКО. Принципы права социального de Justiţie, Ministerul Afacerilor Interne, Institutul обеспечения: мировые стандарты ........................................ 22 de Ştiinţe Penale şi Criminologie Aplicată, Institutul de cercetări Juridice și Politice al Academiei de Мария ГУДЫМА-ПИДВЕРБЕЦКАЯ. Ştiinţe a Moldovei, Academia ,,Ştefan cel -

1 4) Survivor Testimonies, Memoirs, Diaries, And

4) SURVIVOR TESTIMONIES, MEMOIRS, DIARIES, AND LETTERS Introduction The fourth section of the Reader consists of testimonies, memoirs, and letters by famine victims. Most are by ordinary folk and are usually of a personal nature. At the same time, they provide a plethora of oftentimes painful and gut-wrenching details about the fate of family members and particular villages. Interestingly, several testimonies emphasize the limitation of the famine to Ukraine, noting that conditions just across the border in Russia were significantly better. A letter from German settlers in southern Ukraine to their relatives in North Dakota illustrates the fate of the German minority in Ukraine during the famine. Some testimonies were given before U.S. government-sponsored investigative bodies. Some, such as those published in The Black Deeds of the Kremlin, were collected and published by Ukrainian émigrés and Holodomor survivors at the height of the Cold War. This made it easy for those holding pro-Soviet views to dismiss them as anticommunist propaganda. A noteworthy personal account is that of Maria Zuk, who emigrated from southern Ukraine to western Canada to join her husband in the late summer of 1933, when she gave her interview to journalists working for a Ukrainian- language newspaper in Winnipeg. Another is Miron Dolot’s Execution by Hunger, published by a major American press in 1985. This section also contains materials from non-peasants: Fedir Pigido- Pravoberezhny, who worked as an engineer in Ukraine; Yurij Lawrynenko and Mykola Prychodko, both literary scholars; and Vladimir Keis, an urban worker at the time of the famine who retained strong ties with the Ukrainian village. -

Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis Nicholas Pehlman The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3073 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © Copyright by Nick Pehlman, 2018 All rights reserved ii Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Mark Ungar Chair of Examining Committee Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Julie George Jillian Schwedler THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional -

Antonovych Myroslava

Dr Myroslava Antonovych Doctor of Law (Germany), Candidate of Philology, Associate Professor of the International and European Law Department, Director of the Center for International Human Rights, Law School, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy https://scholar.google.com.ua/citations?user=Ts9GKKgAAAAJ https://ukma.academia.edu/MyroslavaAntonovych https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Myroslava_Antonovych http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1803-5079 Сurrent Business Address: Law School, University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy 2 Skovoroda St. Kyiv 04070 Ukraine Tel.: (380-44) 425-6073; Fax: (380-44) 463-7109 e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Education 2008 UWU, Munich, Germany, Doctor of Law Magna Cum Laude 1999 McGill University, Canada, LL.M. 1995 Lviv National University, Ukraine, Degree in Law 1988 Kyiv Linguistic University, Ukraine, Candidate of Philology (English) 1981 Dnipropetrovsk State University, Ukraine, Degree in English, with honors 1976 Novyi Rozdol High School, Ukraine, with Gold Medal Professional experience 2010 – by now National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Kyiv Director of the Center for International Human Rights 2010 - 2014 Judge ad hoc of the European Court of Human Rights 2006 - 2015 National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Kyiv Head of International Law Department, Law School 2000 - 2001 Commercial Law Center, USAID, Kyiv Professional Development Director (part-time) 1999 - 2000 National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Kyiv Executive Director of the Legal Information Research Center, 1998 -

English%20FINAL.Pdf

ALMANAC ON SECURITY SECTOR GOVERNANCE IN UKRAINE 2012 Geneva-Kyiv, 2013 Editors: Joseph L. DERDZINSKI, Valeriya KLYMENKO Design and layout: Oleksandr SHAPTALA This volume offers a selection of articles by the Ukrainian and international authors. They present different points of view and assessments of the current state and perspectives of the Ukrainian Security Sector development including its defence, internal security and defence industry. The analysis also covers broader issues of national domestic and foreign policy directly infl uencing security of the Ukrainian citizens, society and the state. Such an approach helps better appreciate ongoing developments in the Security Sector and the essence of problems related to national security. General assessments, conclusions and proposals are those of the authors and do not necessarily coincide with the positions of DCAF or the Razumkov Centre. Publication was made possible in the framework of NATO-Ukraine Partnership Network and thanks to the fi nancial support of the Swiss Ministry of Defence Partnership for Peace programme © DCAF, 2013 © Razumkov Centre, 2013 ISBN 978-966-7272-93-7 © “Zapovit” Publishing House, 2013 А Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS . .7 FOREWORD Philipp FLURI . .9 SECURITY SECTOR Chapter 1. SECURITY SECTOR IN THE CONTEXT OF GENERAL SOCIO-POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT OF UKRAINE Oleksiy MELNYK, Mykola SUNGUROVSKYI . .13 Chapter 2. UKRAINE’S SECURITY SECTOR MANAGEMENT SYSTEM: A MODERNISED SOVIET MODEL Oleksandr LYTVYNENKO . .29 Chapter 3. UKRAINE’S SECURITY: PROGRESS AND REGRESSION James SHERR . .37 DEFENCE SECTOR Chapter 4. NEW MILITARY DOCTRINE: PRINCIPLES OF UKRAINE’S MILITARY POLICY IN THE CONDITIONS OF A NON-BLOC STATUS Volodymyr MOZHAROVSKYI, Oleksandr ZATYNAIKO, Viktor PAVLENKO, Viktor BOCHARNIKOV, and Serhiy SVESHNIKOV . -

Antonovych Myroslava

Dr Myroslava Antonovych, LLM McGill Сurrent Business Address: Law School, University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy 2 Skovoroda St. Kyiv 04655 Ukraine Tel.: (380-44) 425-6073; Fax: (380-44) 463-7109 e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Education 2008 UWU, Munich, Germany, Doctor of Law Magna Cum Laude 1999 McGill University, Canada, LL. M. 1995 Lviv National University, Ukraine, Degree in Law 1988 Kyiv Linguistic University, Ukraine, Candidate of Philology (English) 1981 Dnipropetrovsk State University, Ukraine, Degree in English, with honors 1976 Novyi Rozdol High School, Ukraine, with Gold Medal Professional experience 2009 - 2014 Judge ad hoc of the European Court of Human Rights 2006 - by now National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Kyiv Head of International Law Department, Law School 2000 - 2001 Commercial Law Center, USAID, Kyiv Professional Development Director (part-time) 1999 - 2000 Legal Information Research Center, University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Executive Director 1998 - by now University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Associate Professor, Law School 1998 - 2001 Center for Legal Studies, Ukrainian Legal Foundation, Kyiv Associate Professor, Department of Constitutional and Municipal Law (part-time) 1988 - 1998 Precarpathian State University, Ivano-Frankivsk Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, English Department Visiting Positions and Research Affiliations 2013- Visiting Professor, Faculty of State and Economics, Ukrainian Free University, 2015 Munich 2010 Visiting Professor, Faculty of Law, Washington and Lee University, -

For Free Distribution

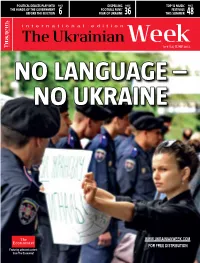

POLITICAL DEUCES PLAY INTO PAGE DISPELLING PAGE TOP 12 MUSIC PAGE THE HANDS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOOTBALL FANS' FESTIVALS BEFORE THE ELECTION 6 FEAR OF UKRAINE 36 THIS SUMMER 48 № 9 (32) JUNE 2012 NO LANGUAge – NO UKRAINE WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION Featuring selected content from The Economist Opposition vote |CONTENTS BRIEFING FOCUS ealers 9.8- Russification Redux? Total Political(eimates b yDeuces: A Royal Gift for the Language policy of the TPseudo-oppositionhe Ukrainian Government: A slew of facts party in power puts the projectsWeek) are stealing11.5 signal that the Presidential Ukrainian language the opposition’s Administration is promoting as well as Ukraine’s votes and play Natalia Korolevska’s political sovereignty and European foul in electoral project to help it take control choice at risk 4 commissions 6 of the future parliament 8 POLITICS Why Invest in European Stories: Matej Šurc and Blaž Culture? How Leonidas Donskis Zgaga investigate 5.4 2.9 – 0.4 0.3▪ 0.5- Ukrainian – on the role of0.7 the role of Slovenian officials4.1 are 3.1 1.6 literature and and Ukrainian top distorting storytelling in officials in arms Ukrainian politics trade with the cultureNatalia Hr10omadianska Nasha Oleh Ukrainian Others 12 Balkans 13 Korolevska's pozytsia Ukrayina Liashko's People's (eimates NEIGHBOURS SECURITY Ukrayina - (Civil (Our Radical Party by The The Difficult Vpered! Position) UkrEdwardaine) ChowPart ony how Ukrainian Bernard Path towards (Ukraine - Forwrwaarrdd!)!) Ukrainian authorities Week) Kouchner: Security Reform can decrease If you want to live in Ukraine dependence on Russian in a better world, Support from voters gas, yet put themselves it's all possible intending to vote in the eleion, % 16 in an ever worse 18 in the EU 20 Based position instead 0,0 on Razumkov ECONOMICS Centre poll held INVESTIGATION on 14-19 April 23.3 2012 The Illusion of Reforms26.7 According to Armed and 7.7 10.1 5.7 Based Macroeconomic28.2 Schumpeter: Unpunished: The 0,0 28.6 5.1 on KMIS Stability: why 8.5 The book confirms that10. -

EU-Forest-Crime-Initiative-Ukraine

1 Photos credit: © WWF-Ukraine Published in August 2020 by WWF – World Wide Fund For Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund), Brussels, Belgium. Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © Text 2020 WWF. All rights reserved. The content of this publication represents the views of WWF only and is its sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains. This project was funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund — Police Project-Nr. "821579 -Forest Crime - ISFP-2017-AG-ENV" 2 Illegal logging accounts for as much as 10–30 % of the total logging worldwide, with some estimates as high as 20–50 %1 when laundering of illegal wood is included, with a growing involvement of organized crime. A significant proportion of forestry crimes are now carried out by organized criminal networks utilising an international network of quasi-legitimate businesses and corporate structures to hide their illegal activities, which include creative accounting to launder criminal proceeds or collusion with senior government officials. Organized forest crime continues to evolve and develop new methods to conduct forestry crime operations and launder illegal timber. In the Danube-Carpathian Region and Ukraine, forestry crime is a recognised problem, damaging Europe’s last primeval forests and undermining government policies to sustainably manage and protect forests. Depending on sources and dates, estimates of illegal logging range from 0,1% to 40% throughout the country. Though the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR) came into force in 2013 to stop illegal wood and paper products being placed on the European market, the EUTR and national laws in Ukraine against forestry crimes have up to now not been implemented with full effect due to different gaps and obstacles. -

1 January 5, 1997

INSIDE: • A look at five years of Ukraine’s independence — page 2. • Ukrainian Christmas symbolism — page 8. • Yara Arts Group in Buryatia — page 9. HE KRAINI A N EEKLY T PublishedU by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profitW association Vol. LXV No. 1 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 5, 1997 $1.25/$2 in Ukraine Kuchma thanks diaspora for support Conference reflects on 20 years WASHINGTON — In a special mes- our victories. 1996 is marked by one of the sage to “our brothers and sisters abroad,” most important victories: the adoption of President Leonid Kuchma thanked the Constitution of Ukraine, which codified of Ukrainian human rights activism by Irene Jarosewich a security and cooperation agreement to Ukrainians of the diaspora for “decades of our achievements in the process of state- which the government of the USSR was work at the time of the Iron Curtain’s exis- building, delineated further steps in its NEW YORK — Twenty years ago, a s i g n a t o r y . tence that created a positive posture toward development and became the fundamental small group of determined individuals To commemorate the 20th anniversary Ukraine” and five years ago resulted in consolidating factor of our society. gathered together with a pledge to unveil of the founding of the UHG, its External speedy recognition of its independence. “I want to sincerely thank all of you, the hypocrisy of the Soviet system, to Representation in the United States orga- Addressing his fellow Ukrainians dear countrymen in the U.S.A. and Canada, reveal its oppressive grip on the lives of nized a conference held on December 15, around the world just over five years Great Britain and Australia, France and its citizens and the brutality with which it 1996, at the Shevchenko Scientific Society since Ukraine declared its independence Germany, Brazil and Argentina, Russia and treated its opponents.