Ceramic Diversity and Its Relation to Access to Market for Slaves on a Plantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820 Christian Pinnen University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pinnen, Christian, "Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820" (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen May 2012 “Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720- 1820,” examines how slaves and colonists weathered the economic and political upheavals that rocked the Lower Mississippi Valley. The study focuses on the fitful— and often futile—efforts of the French, the English, the Spanish, and the Americans to establish plantation agriculture in Natchez and its environs, a district that emerged as the heart of the “Cotton Kingdom” in the decades following the American Revolution. -

Cultural Resources Overview

United States Department of Agriculture Cultural Resources Overview F.orest Service National Forests in Mississippi Jackson, mMississippi CULTURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW FOR THE NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI Compiled by Mark F. DeLeon Forest Archaeologist LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI USDA Forest Service 100 West Capitol Street, Suite 1141 Jackson, Mississippi 39269 September 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures and Tables ............................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 1 Cultural Resources Cultural Resource Values Cultural Resource Management Federal Leadership for the Preservation of Cultural Resources The Development of Historic Preservation in the United States Laws and Regulations Affecting Archaeological Resources GEOGRAPHIC SETTING ................................................ 11 Forest Description and Environment PREHISTORIC OUTLINE ............................................... 17 Paleo Indian Stage Archaic Stage Poverty Point Period Woodland Stage Mississippian Stage HISTORICAL OUTLINE ................................................ 28 FOREST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ............................. 35 Timber Practices Land Exchange Program Forest Engineering Program Special Uses Recreation KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE FOREST........... 41 Bienville National Forest Delta National Forest DeSoto National Forest ii KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE -

Spring/Summer 2016 No

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXVIII Spring/Summer 2016 No. 1 and No. 2 CONTENTS Introduction to Vintage Issue 1 By Dennis J. Mitchell Mississippi 1817: A Sociological and Economic 5 Analysis (1967) By W. B. Hamilton Protestantism in the Mississippi Territory (1967) 31 By Margaret DesChamps Moore The Narrative of John Hutchins (1958) 43 By John Q. Anderson Tockshish (1951) 69 By Dawson A. Phelps COVER IMAGE - Francis Shallus Map, “The State Of Mississippi and Alabama Territory,” courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. The original source is the Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection. Recent Manuscript Accessions at Mississippi Colleges 79 University Libraries, 2014-15 Compiled by Jennifer Ford The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi Museum Store; call 601-576-6921 to check availability. The Journal of Mississippi History is a juried journal. Each article is reviewed by a specialist scholar before publication. Periodicals paid at Jackson, Mississippi. Postmaster: Send address changes to the Mississippi Historical Society, P.O. Box 571, Jackson, MS 39205-0571. Email [email protected]. © 2018 Mississippi Historical Society, Jackson, Miss. The Department of Archives and History and the Mississippi Historical Society disclaim any responsibility for statements made by contributors. INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction By Dennis J. Mitchell Nearing my completion of A New History of Mississippi, I was asked to serve as editor of The Journal of Mississippi History (JMH). -

MSSDAR STATES CATALOG Updated 10/4/14 Bobby L. Lindsey

MSSDAR STATES CATALOG Alabama Barbour / Henry Newspapers Barbour & Henry County Newspaper Notices Alabama Chambers History The Reason for the Tears, A History of Chambers Co., AL 1832-1900 Bobby L. Lindsey Alabama Etowah CO Heritage The Heritage of Etowah County, Alabama Vol. 28 Alabama Fayette History 150 Yesteryears: Fayette County, Alabama Alabama Greene History A Goodly Heritage: Memories of Greene County, AL Alabama Henry History History of Henry County, Alabama Alabama Jefferson Death/Marriage Death & Marriage Notices from Jefferson Co., AL newspapers Volume II 1862-1906 Alabama Jefferson Death/Marriage Death & Marriage Notices from Jefferson Co., AL newspapers Volume II 1862-1906 Alabama Lamar Co. Vernon Links to Lamar County, Vernon, Alabama Alabama Montgomery Newspapers Death/ Marriage/Probate Rec Fr Montgomery, AL Newspapers Vol I, 1820-1865 Alabama Montgomery Newspapers Death/ Marriage/Probate Rec Fr Montgomery, AL Newspapers Vol II 1866-1875 Caver Alabama Randolph Historical Sketches of Randolph County, AL Alabama Washington Tax Rolls Washington County, Mississippi Territory, 1803-1817, Tax Rolls Alabama WashinGton History History of Washington County (Alabama) Alabama Washington Residents of the Southeastern Mississippi Territory / Washington and Baldwin Counties, Alabama / Wills Baldwin Deeds and Superior Court Minutes Book Five Alabama 1820 Census Alabama Census Returns of 1820 Alabama 1840 Census Alabama 1840 Census Index Volume I: The Counties formed from the Creek and the Cherokee Cessions of the 1830's Alabama DAR Alabama Regents (DAR) 1894-1973 Alabama Families History and genealogy of some pioneer northern Alabama families Alabama General Alabama Notes Volumes I & II (1 book) Alabama History Report of the Alabama Historical Society (1901) Alabama Rev Soldiers A Roster of Revolutionary Soldiers and Patriots in Alabama L. -

![X] Structure S Private D '" Process IAJ Unoccupied Jj-.-J](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1537/x-structure-s-private-d-process-iaj-unoccupied-jj-j-1311537.webp)

X] Structure S Private D '" Process IAJ Unoccupied Jj-.-J

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Mississippi COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Claiborne INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) nrr 2 7 4974 '.T.n.'.'i1 ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^Ki^^^^^^^^^^^ COMMON: Buena Vista Cotton Gin AND/ OR HISTORIC: Watson Steam Gin Hi! .STREET AND,NUMBER: A" f~ !~~^ } < ' ._ Township 12 N, Range 3 E, Section 55 (irregular) CITY OR TOWN: COr 4GRESSIONAL DISTRICT: -Rear "Port Gibson - V Fourth ST * TE CODE COU NTY: CODE Mississippi 39150 28 C Laiborne 021 STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC | | District Q Building CH Public Public Acquisition: D Occupied Yes: rrn 1 1 .1 I I Restricted D Site [X] Structure S Private D '" Process IAJ Unoccupied jj-.-j . _ , 1 1 Unrestricted Q Object D Botn S Being Cons iderea Q Preservation work * J ~ in progress IC-J PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government [ | Park I | Transportation 1 1 Comments nCommercial d Industrial fj Private Residence 51 Other (Sper.ify) . O Educational d Military Q Religious Abandoned [ | Entertainment [~~l Museum | | Scientific .,.»., ,. SSSSSB^^ :::;:¥::::i::;:;J:::S::*:;:S:::j;::::M::5S^ OWNER'S NAME: STATE' Charles E. Bar land and Harold Barland Mississippi STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: STATE: 'ZODE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 28 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: o 8 Claiborne County Courthouse M c P z STREET AND NUMBER: o*H- H-< Market Street at Orange o CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE rt» Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 28 J t TITLE OF SURVEY: X ^ ~^C/'^u\. -

Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J. McCall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McCall, Ronald J., "Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1121. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1121 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move __________________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ___________________________ by Ronald J. McCall May 2013 ________________________ Dr. Steven N. Nash, Chair Dr. Tom D. Lee Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Family History, Southern Plain Folk, Herder, Mississippi Territory ABSTRACT Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move by Ronald J. McCall This thesis explores the settlement of the Mississippi Territory through the eyes of John Hailes, a Southern yeoman farmer, from 1813 until his death in 1859. This is a family history. As such, the goal of this paper is to reconstruct John’s life to better understand who he was, why he left South Carolina, how he made a living in Mississippi, and to determine a degree of upward mobility. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

. ~-tJ Nil LlJ S r A 1 LS DLPi\ RTMENT OF THE I NTERIOR FOR NPS USE ONLY , NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEI VEQ INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE EN TER ED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORM S TY PE ALL ENT RI ES -- COM PL ETE APPLICA BLE SECTION S ONAME HISTORIC AND/ OR COMMON .. :J IIi storje ReSO l1 rces Of Port Gjhson (Partial Inventory : Historic and Architec tural Sites) DLOCATION ',...(~~tI<o STREET & NUMBER "-. not e c1. I The incorporated limi ts of the City of Port Gibson except a~NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Port Gibson VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi .', 28 Claiborne 21 DCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESE NT USE _DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED UGRICULTURE _MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _ PRIVATE X-U NOCCU PIE D x...CDMMERCIAL _ PARK _STRUCTURE XBOTH X-WDRK IN PROGRESS llEDUCATIONAL A.PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE P UBLIC ACQUISIT ION ACCESSIBLE llENTERTAINMENT ~ RELIGIOUS _ OBJECT _ IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTR ICTED x...GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC ~HultipJ.e Resource _ BEING CONSIDERED x... YES: UNRESTRICTED X-'NDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION _ NO _ MILITARY x... OTHEiCem e t e rie~ DOWNER OF PR OPERTY NA ME M!!J tipJ e Ownership STREET & NUMBER - - --- - ---.. - ----------:S=T-:-:AT=E------~- CITY. TOWN _ VICINITY OF DLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Office of the Chancery Clerk, Claiborne County Courthous e STREET & NUMBER 410 Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississip~i 39150 o REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE Sta t e wid e Survey of Historic Sites DATE ~~~~--------------------- 1978 , 1979 _ FEDERAL -XSTATE _ COUNTY _ LOCAL DEPOSITOR Y FOR SU RVE Y REC ORDS Mississippi Department of Archi ves an!!.\..!d---...llH...!.iJ;lsu.t...l,oQ1.J.r-)y~_---::-:::-:-=-::--_________ CI TY . -

6 European Colonization in Mississippi

6 EUROPEAN COLONIZATION IN MISSISSIPPI1 JACK D. ELLIOTT, JR. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this report is to identify the cultural resources of Mississippi pertaining to the Period of European Colonization. The cultural resources include both sites and buildings. The term “sites” is the more inclusive of the two terms. Sites are the places at which past activities occurred and consequently include sites on which are located historic building, sites with archaeological remains, and even sites which were the scenes of past activities, yet at which there are no extant physical remains other than the physical landscape, associated with those events. The Period of European Colonization is separated from the preceding Period of European Exploration by the beginning of permanent European settlement. Permanent settlement is particularly important for the aspect of historic preservation programs that deal with Euro-American culture in that it marks the inception of a time period in which we first find significant numbers of sites and other remains of occupation. Prior to the beginning of permanent European settlement in Mississippi the European presence was confined to merely sporadic expeditions and wanderers that seldomed on the same site for more than a season at most. Such sites have typically been difficult if not impossible to identify. It has only been with the inception of permanent European settlement that we first have settlements that were sufficiently permanent that they can be identified through maps, written sources, and archaeological remains. Consequently, the distinction between the periods of exploration and colonization is more fundamental than that between the period of colonization and the succeeding periods under American jurisdiction. -

6* I If Frf I I Determined Eligible for the National Register

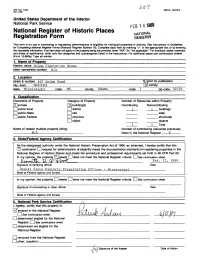

NPS Fwm 10-900 OMB No. 10240018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FEB16 National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1 . Name of Property historic name Selma Plantation House other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 467 Selma Road ftl/Anot for publication city, town Natchez Ixl vicinity state Mississippi code MS county Adams code 1 zip code 39120 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property [X] private [X] building(s) Contributing Noncontributing I I public-local I I district 1 buildings I I public-State I [site ____ sites I I public-Federal I I structure ____ structures I I object ____ objects 1 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously _______N/A____________ listed in the National Register 0_____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this H nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta As Plantation Country

The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta as Plantation Country JOHN C. HUDSON Professor of Geography Northwestern University Evanston, Illinois 60201 "The Mississippi Delta," wrote David Lewis Cohn, "begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg, "1 Cohn's depression-era account is past history. The shell of the Peabody is no longer a fit place for the planter aristocaracy to mingle, and Catfish Row in Vicksburg is mere ly a memory of the black culture that once flourished in the Delta. In between these two cities that bound the Delta on the north and south, the four and one-half million acres of this great alluvial empire are still yielding the bumper crops that have kept the Delta among the richest agricultural regions of the nation for decades. The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta is plantation country, and it has been plantation country ever since the Choctaw cession of 1820 opened the lower end of the basin to settlement. In 1860, at the height of the prewar cotton prosperity, only nine of the 95 agricultural operators in Issaquena County, Mississippi, owned no slaves, compared with a state-wide average of approximately 50 percent nonslave owners. 2 Today's Delta plantation is a far cry from the fabled antebellum estate, but it is hard to think of any region in the South where there are more self-proclaimed planters and fewer just plain farmers than in the Delta. The continuity of the planter tradition was not a foregone conclu sion. In fact, the largest landowners were not planters at all. -

The Theatre in Mississippi from 1840 to 1870. Guy Herbert Keeton Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 The Theatre in Mississippi From 1840 to 1870. Guy Herbert Keeton Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Keeton, Guy Herbert, "The Theatre in Mississippi From 1840 to 1870." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3399. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3399 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Pagefs)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing pagefs) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

The Development of the Natchez District, 1763-1860 Lee Davis Smith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2004 A settlement of great consequence: the development of the Natchez District, 1763-1860 Lee Davis Smith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Lee Davis, "A settlement of great consequence: the development of the Natchez District, 1763-1860" (2004). LSU Master's Theses. 2133. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2133 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SETTLEMENT OF GREAT CONSEQUENCE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1763 - 1860 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Lee Davis Smith B.A., Louisiana State University, 2002 August, 2004 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Tiwanna M. Simpson for her careful guidance and steadfast support throughout the process of writing this thesis. Her ability to give me freedom, yet reel me back in when necessary, has been invaluable. I treasure her friendship and her counsel. Dr. Rodger M. Payne has opened my eyes to the true significance of religion in America, and I thank him for shining a spotlight where I had previously held a candle.