UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Commodification, Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Ofthe Council

Report ofthe Council October 21, ip8y AN ANNUAL MEETING marks the end ofan old year and the be- ginning of a new one. In that respect, this one is no different from the previous 174 during which you, our faithful members (or your predecessors), have suffered through narrations about the amazing successes, the fantastically exciting acquisitions, and the continu- ing upward ascent of our great and ever more elderly society. But this year has been a remarkable one for the American Antiquarian Society in terms of change, achievement, and, now, celebration. In this country, there are not very many secular institutions more ancient than ours, certainly not cultural ones—perhaps sixty col- leges, a handful of subscription libraries, a few learned societies. For 175 years we, and our friends of learning, have built and strengthened a great research library and its staff; have presented our collections to scholars and students of American history and life through service and publications; and now, at the beginning of our 176th year, are looking forward to new challenges to enable the Society to become even more useful as an agency of learning and to the understanding of our national life. Dealing with change takes first place in daily routine and there have been many important ones during the past twelve months, more so than in recent memory. Among the membership we lost a longtime friend and colleague, John Cushing. John served as librarian of the Massachusetts Historical Society since 1961 and during this past quarter century had been our constant col- laborator in worthwhile bibliographical and historical enterprises. -

The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2012 Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820 Christian Pinnen University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pinnen, Christian, "Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820" (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND EMPIRE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF SLAVERY IN THE NATCHEZ DISTRICT, 1720-1820 by Christian Pinnen May 2012 “Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720- 1820,” examines how slaves and colonists weathered the economic and political upheavals that rocked the Lower Mississippi Valley. The study focuses on the fitful— and often futile—efforts of the French, the English, the Spanish, and the Americans to establish plantation agriculture in Natchez and its environs, a district that emerged as the heart of the “Cotton Kingdom” in the decades following the American Revolution. -

ACADIA PLANTATION RECORDS Mss

ACADIA PLANTATION RECORDS Mss. 4906 Inventory Compiled by Catherine Ashley Via and Rebecca Smith Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana 2005 Revised 2015 Updated 2020, 2021 ACADIA PLANTATION RECORDS Mss. 4906 1809-2004 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, LSU LIBRARIES CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 4 HISTORICAL NOTE ..................................................................................................................... 5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ............................................................................................................... 8 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................. 10 LIST OF SERIES AND SUBSERIES .......................................................................................... 11 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS ............................................................................................................ 12 INDEX TERMS ............................................................................................................................ 25 CONTAINER LIST ...................................................................................................................... 28 Appendix A: Oversized materials from Series II, Legal Records, Subseries 1, General Appendix B: Oversized -

Cultural Resources Overview

United States Department of Agriculture Cultural Resources Overview F.orest Service National Forests in Mississippi Jackson, mMississippi CULTURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW FOR THE NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI Compiled by Mark F. DeLeon Forest Archaeologist LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI USDA Forest Service 100 West Capitol Street, Suite 1141 Jackson, Mississippi 39269 September 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures and Tables ............................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 1 Cultural Resources Cultural Resource Values Cultural Resource Management Federal Leadership for the Preservation of Cultural Resources The Development of Historic Preservation in the United States Laws and Regulations Affecting Archaeological Resources GEOGRAPHIC SETTING ................................................ 11 Forest Description and Environment PREHISTORIC OUTLINE ............................................... 17 Paleo Indian Stage Archaic Stage Poverty Point Period Woodland Stage Mississippian Stage HISTORICAL OUTLINE ................................................ 28 FOREST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ............................. 35 Timber Practices Land Exchange Program Forest Engineering Program Special Uses Recreation KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE FOREST........... 41 Bienville National Forest Delta National Forest DeSoto National Forest ii KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE -

Land Surveying in Alabama J. M. Faircloth

LAND SURVEYING IN ALABAMA J. M. FAIRCLOTH PREFACE There are numerous treatises on land surveying available to the engineer or surveyor today. The legal, theoretical, and practical aspects of general land surveying are all easily available in great detail.* However, there is no writing known to the author which deals specifically with surveying in Alabama or which touches in any appreciable degree upon the problems encountered in Alabama. This manual is not intended to cover the general type of material easily available in the usual surveying text, the manual of the U.S. Land Office or the many other references on surveying; but rather is intended to supplement these writings with information specific to Alabama. The author recognizes a growing need in Alabama for some source of information for the young land surveyor. Few colleges continue to include courses in land surveying in their required curricula, and few references are made to land surveying in the engineering courses on surveying. The increasing values of real property creates a growing public demand for competent land surveyors. The engineering graduate has little training or background for land surveying and has no avenue available for obtaining this information other than through practical experience. One of the purposes of this manual is to provide some of this information and to present some of the problems to be encountered in Alabama. The Board of Licensure for Professional Engineers and Land Surveyors in Alabama is faced with the problem of a large public demand for land surveyors that cannot be filled on the one hand, and the maintenance of high professional standards with adequate means for training land surveyors on the other. -

Spring/Summer 2016 No

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXVIII Spring/Summer 2016 No. 1 and No. 2 CONTENTS Introduction to Vintage Issue 1 By Dennis J. Mitchell Mississippi 1817: A Sociological and Economic 5 Analysis (1967) By W. B. Hamilton Protestantism in the Mississippi Territory (1967) 31 By Margaret DesChamps Moore The Narrative of John Hutchins (1958) 43 By John Q. Anderson Tockshish (1951) 69 By Dawson A. Phelps COVER IMAGE - Francis Shallus Map, “The State Of Mississippi and Alabama Territory,” courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. The original source is the Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection. Recent Manuscript Accessions at Mississippi Colleges 79 University Libraries, 2014-15 Compiled by Jennifer Ford The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi Museum Store; call 601-576-6921 to check availability. The Journal of Mississippi History is a juried journal. Each article is reviewed by a specialist scholar before publication. Periodicals paid at Jackson, Mississippi. Postmaster: Send address changes to the Mississippi Historical Society, P.O. Box 571, Jackson, MS 39205-0571. Email [email protected]. © 2018 Mississippi Historical Society, Jackson, Miss. The Department of Archives and History and the Mississippi Historical Society disclaim any responsibility for statements made by contributors. INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction By Dennis J. Mitchell Nearing my completion of A New History of Mississippi, I was asked to serve as editor of The Journal of Mississippi History (JMH). -

View National Register Nomination Form

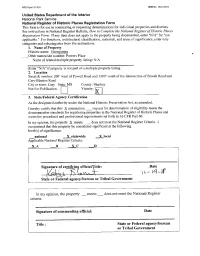

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Name of Property Georgianna County and State: Sharkey County, Mississippi ______________________________________________________________________________ 4. National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register determined eligible for the National Register determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain:) _____________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Signature of the Keeper Date of Action ____________________________________________________________________________ 5. Classification Ownership of Property (Check as many boxes as apply.) Private: X Public – Local Public – State Public – Federal Category of Property (Check only one box.) X Building(s) District Site Structure Object Sections 1-6 page 2 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Name of Property Georgianna County and State: Sharkey County, Mississippi Number of Resources within Property (Do not include previously listed resources in the count) Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings _____________ 1 sites 1 (cistern) structures _____________ _____________ objects ____2_________ _______1_______ Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National -

Length Conversion Table

Category: Length / Distance Provided by: Smart Conversion SmartConversion URL: http://www.smartconversion.com Conversion Table: Length / Distance Unit Name Relation to: meter [m] ångström [Å] 1E-10 [m] arm length 0.7 [m] arpent length [Canada] 58.5216 [m] astronomical unit [AU] 1.495979E+11 [m] big point [bp][Adobe] 3.527778E-4 [m] cable length [UK imperial] 185.3184 [m] cable length [international] 185.2 [m] cable length [US] 219.456 [m] caliber 2.54E-4 [m] chain [ch][Engineer, Ramsden's chain] 30.48 [m] chain [ch][metric] 20 [m] chain [ch][Survey, Gunter's chain] 20.1168 [m] chi [China] 0.35814 [m] click [US military] 1000 [m] cubit 0.4572 [m] didot point [Adobe] 3.527778E-4 [m] didot point [Europe] 3.77E-4 [m] digit [Europe] 0.019 [m] douzième 1.88E-4 [m] ell [ell][English] 1.143 [m] em 3.527337E-4 [m] fall [English] 6.858 [m] fall [Scotland] 5.67 [m] fathom [fth] 1.8288 [m] fermi [fm] 1E-15 [m] finger 0.022225 [m] finger [cloth] 0.1143 [m] fist 0.1 [m] fod [Danish] 0.3141 [m] foot [ft][international] 0.3048 [m] foot [ft][US, survey] 0.304800609601219 [m] football field [Canada] 100.584 [m] football field [US] 91.44 [m] furlong [fur] 201.168 [m] Category: Length / Distance Provided by: Smart Conversion SmartConversion URL: http://www.smartconversion.com gauge [standard] 1.435 [m] goad 1.3716 [m] hand 0.1016 [m] heer [cloth] 73.152 [m] inch [in][international] 0.0254 [m] inch [in][US, survey] 0.025400051 [m] klafter 1.8288 [m] lap [international] 400 [m] league [lea] 4828.032 [m] li 500 [m] light-second 2.997925E+8 [m] light-year [l.y.] -

Charles University in Prague Faculty of Social Sciences The

Charles University in Prague Faculty of Social Sciences Institute of International Studies Department of American Studies The Aspirations and Ascent of George Washington in the Context of His Times: From His Early Years to the End of the Revolutionary War Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Author: Mgr. Stanislav Sýkora Supervisor: Prof. PhDr. Svatava Raková, CSc. Year: 2012 ABSTRACT George Washington’s relatively obscure beginnings did not preclude him from admiring and acquainting himself with chivalrous role models and genteel guidelines. Longing for recognition, Washington sought opportunities to serve his influential patrons to merit their further approbation. The dissertation sets Washington’s aspirations in the context of honor-based sociocultural milieu of his day and thus provides the reader with an insight into the conventional aspects of his ascent to the upper echelons of the colonial society of Virginia. At the time of the Revolution, Washington’s military reputation, leadership, and admirable character earned him a unanimous election to the chief command of the American armies. The complexity of Washington’s venture of accepting, exercising, and ultimately resigning the supreme military powers in relation to his reputation and sense of patriotic duty is thoroughly analyzed. Key words: George Washington, convention, ascent, ambition, patriotism, virtue iii I declare that I have worked on this dissertation independently, using the sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………… Author’s signature iv CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter One: The Early Influences 11 Chapter Two: “Honour and Glory” 42 Chapter Three: The Gentleman of Mount Vernon 113 Chapter Four: “It Surely Is the Duty of Every Man Who Has Abilities to Serve His Country” 123 Chapter Five: “My Plan Is to Secure a Good Deal of Land” 168 Chapter Six: “Certain I Am No Person in Virginia Takes More Pains to Make Their Tobo Fine than I Do” 184 Chapter Seven: “George Washington, Esq. -

1 Record Group 1 Judicial Records of the French

RECORD GROUP 1 JUDICIAL RECORDS OF THE FRENCH SUPERIOR COUNCIL Acc. #'s 1848, 1867 1714-1769, n.d. 108 ln. ft (216 boxes); 8 oversize boxes These criminal and civil records, which comprise the heart of the museum’s manuscript collection, are an invaluable source for researching Louisiana’s colonial history. They record the social, political and economic lives of rich and poor, female and male, slave and free, African, Native, European and American colonials. Although the majority of the cases deal with attempts by creditors to recover unpaid debts, the colonial collection includes many successions. These documents often contain a wealth of biographical information concerning Louisiana’s colonial inhabitants. Estate inventories, records of commercial transactions, correspondence and copies of wills, marriage contracts and baptismal, marriage and burial records may be included in a succession document. The colonial document collection includes petitions by slaves requesting manumission, applications by merchants for licenses to conduct business, requests by ship captains for absolution from responsibility for cargo lost at sea, and requests by traders for permission to conduct business in Europe, the West Indies and British colonies in North America **************************************************************************** RECORD GROUP 2 SPANISH JUDICIAL RECORDS Acc. # 1849.1; 1867; 7243 Acc. # 1849.2 = playing cards, 17790402202 Acc. # 1849.3 = 1799060301 1769-1803 190.5 ln. ft (381 boxes); 2 oversize boxes Like the judicial records from the French period, but with more details given, the Spanish records show the life of all of the colony. In addition, during the Spanish period many slaves of Indian 1 ancestry petitioned government authorities for their freedom. -

James' River Guide

7 '^^^^ « THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS :/ m LIBRARY an. t * IILINOIS HISTORICAL SURVEY T^T^i^-'. ** ... >^ ^.^ ^y JAMES' K I V E R GUIDE: CONTAINING DESCKIPTIONS OF ALL THE CITIES, TOWNS, AND PEINCIPAL OBJECTS OF INTEREST, ON THE NAVIGABLE TITERS OF THE MISSISSIPPI VALLEY, FLOWING WEST FROM THE ALLEOnANY MOUNTAINS, EAST FROM THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS, AND SOUTH FROM NEAR THE NORTHERN LAKES, INCLUDING THE RIVERS OF ALABAMA AND TEXAS, FLOWING INTO THE GULF OF MEXICO : ALSO, AN ACCOUNT OF THE SOURCES OF THE RIVERS; WITH , FULL TABLES OF DISTANCES, AND MANY INTERESTING HISTORICAL SKETCHES OF THE COUNTRY, STATISTICS OF POPULATION, PRODUCTS, COJIMERCE, MANUFACTtTRES, MINERAL BB- SOURCES, Scenery, &c., &c. ILLUSTRATED WITH FORTY-FOUS MAPS, AND A NUMBER OF ENGRAVINGS. ^"' t. CINCINNATI: PUBLISHED BY U. P. JAMES. '* 167 WALNUT STREET. 1857. PUBLISIIEE^S NOTICE. The former edition of the River Guide, published under the name of " Conclms New River Guide," is embodied in this edition so far as it suits the present time. The work has been tliorouglily revised and cor- rected, very much enlarged, in amount of matter, and brought down to the latest date. It is confidently believed that the book is now as com- plete and accurate as it is possible to make a work of this character. To the traveler on the Western Waters desiring correct information respecting the Rivers, Towns, Products and Resources of the country, it will prove an invaluable companion. ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS WORK. Ala. stands for Alabama. Ark. TABLES OF DISTANCES. The jniSSISSIPPl RIV£R, from Fort Kipley to the Guif oi ITIexico. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections________________ 1. Name__________________ historic__________________________________________ and/or common Rodney Center Historic District__________ 2. Location street & number not for publication city, town Lorman vicinity of congressional district Fourth state Mississippi code 28 county Jefferson code 63 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public occupied X agriculture museum building(s) X private X unoccupied _ X commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment X religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered _ X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple Ownership street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description Office of the Chancery Clerk courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. .T» ff<arafm Cmmf-v rjnurthotise street & number Main Street city, town Fayette state Mississippi 39069 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Statewide Survey of Historic Sites has this property been determined elegible? yes no date 1972, 1973 federal X state county local depository for survey records Mississippi Department of Archives and History city, town Jackson state Mississippi 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent X deteriorated X unaltered X original site ^ good ruins X altered moved date X fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The rural town site of Rodney is located in southwestern Mississippi, approximately five miles east of the Mississippi River, ten miles west of the town of Lorman, fifteen miles southwest of Port Gibson, and twenty miles north of Natchez.