Appendix E Recreation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bigelow Masculinity

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Article TOUGH GUY IN DRAG? HOW THE EXTERNAL, CRITICAL DISCOURSES SURROUNDING KATHRYN BIGELOW DEMONSTRATE THE WIDER PROBLEMS OF THE GENDER QUESTION. RONA MURRAY, De Montford University ABSTRACT This article argues that the various approaches adopted towards Kathryn Bigelow’s work, and their tendency to focus on a gendered discourse, obscures the wider political discourses these texts contain. In particular, by analysing the representation of masculinity across the films, it is possible to see how the work of this director and her collaborators is equally representative of its cultural context and how it uses the trope of the male body as a site for a dialectical study of the uses and status of male strength within an imperialistically-minded western society. KEYWORDS Counter-cultural, feminism, feminist, gender, masculinity, western. ISSN 1755-9944 1 Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Whether the director Kathryn Bigelow likes it or not, gender has been made to lie at the heart of her work, not simply as it figures in her texts but also as it is used to initiate discussion about her own function/place as an auteur? Her career illustrates how the personal becomes the political not via individual agency but in the way she has come to stand as a particular cultural symbol – as a woman directing men in male-orientated action genres. As this persona has become increasingly loaded with various significances, it has begun to alter the interpretations of her films. -

Zero Dark Thirty Error

Issue 7 | Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism | 23 troop carrier with no clear sense of destination, speaks again understated performances further serve to create what might as much to a national as a personal loss of purpose, afer the be described as a reality afect. quest is over. Te 9/11 sequence ofers an extreme version of the real- Te flm’s epilogue has received considerable critical atten- ist aesthetic and the rejection of spectacle. From the second tion1; the prologue less so. And where critics do mention it, plane hitting the tower, to the falling man, to the rubble details are ofen misremembered. In an interview with Kyle of ground zero, there are any number of iconic images the Buchanan, screenwriter Mark Boal refects on the difculties flmmakers might have selected to represent the destruction of writing the ‘opening scene’ of Zero Dark Tirty (2013). Te wrought by the attacks. However, what such images have in scene he is referring to in this discussion, however, is the infa- common, what potentially makes them efective as a form of mous torture scene that begins the narrative proper (to which cultural shorthand, also renders them problematic in terms I will return). It is as if he has momentarily forgotten the scene of eliciting a fresh response – and certainly in terms of the Intimacy, ‘truth’ and the gaze: that precedes it in the original shooting script as well as the slow-burn, reality afect. Teir very familiarity can render flm. Given this oversight by the writer himself, it is under- such images hackneyed and over-determined. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

The “Genre Bender”: the Creative Leadership of Kathryn Bigelow

THE “GENRE BENDER”: THE CREATIVE LEADERSHIP OF KATHRYN BIGELOW Olga Epitropaki and Charalampos Mainemelis ABSTRACT In the present chapter, we present the case study of the only woman film director who has ever won an Academy Award for Best Director, Kathryn Bigelow. We analyzed 43 written interviews of Kathryn Bigelow that have appeared in the popular press in the period 1988 2013 and outlined eight main themes emerging regarding her exercise ofÀ leadership in the cinematic context. We utilize three theoretical frameworks: (a) paradoxical leadership theory (Lewis, Andriopoulos, & Smith, 2014; Smith & Lewis, 2012); (b) ambidextrous leadership theory (Rosing, Frese, & Bausch, 2011), and (c) role congruity theory (Eagley & Karau, 2002) and show how Bigelow, as a woman artist/leader working in a complex organizational system that emphasizes radical innovation, exercised paradoxical and ambidextrous leadership and challenged Downloaded by Doctor Charalampos Mainemelis At 07:19 09 March 2016 (PT) Leadership Lessons from Compelling Contexts Monographs in Leadership and Management, Volume 8, 275 300 À Copyright r 2016 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 1479-3571/doi:10.1108/S1479-357120160000008009 275 276 OLGA EPITROPAKI AND CHARALAMPOS MAINEMELIS existing conventions about genre, gender, and leadership. The case study implications for teaching and practice are discussed. Keywords: Creative leadership; ambidextrous leadership; paradoxical leadership; role congruity theory; director; film industry She’s acting out desires. She represents what people want to see, and it’s upsetting, because they don’t know exactly what to do with it. Cultural theorist Sylve´ re Lotringer INTRODUCTION Organizations are abounding with tensions and conflicting demands (e.g., flexibility vs. -

Blurring the Boundaries: Auteurism & Kathryn Bigelow Brenda Wilson

Blurring the Boundaries: Auteurism & Kathryn Bigelow Brenda Wilson Born in California in 1952, Katherine Bigelow is one of group of outsiders living by different rules are presented the few women directors working in Hollywood today. She here as whole- heartedly cool. And the aesthetic style of is exceptional because she works primarily within the the film is indicative of Bigelow's increasingly idiosyncratic traditionally male- dominated genres of the action cinema. choices that create arresting images and innovative action Bigelow's films often reflect a different approach to these sequences. Strange Days (1995) is the film in Bigelow's genres as she consistently explores themes of violence, oeuvre that has received the most critical and theoretical voyeurism and sexual politics. Ultimately she seems to be attention, and so for the purposes of this analysis it will be concerned with calling the boundaries between particular referred to but not fully theorized. Strange Days is a neo- genres into question. Bigelow's visual style echoes this noir science fiction film that presents the future on the eve thematic complexity, often introducing elements of an art- of the new millennium, a dystopic Los Angeles which is on house aesthetic. Bigelow emerged from the New York art the verge of erupting into a race war. The film was a critical scene in the 1970s, having won a Whitney Scholarship to if not commercial success, building upon recognizable study painting. She later transferred to the Columbia Film Bigelow motifs. The film is a rich tapestry of narrative program. Critics such as Yvonne Tasker have commented threads, stunning visuals and soundtrack, all of which on the amalgamation of spectacle and adrenaline with compete for attention. -

A Look at the Forthcoming Remake of Point Break | DIY

10/28/2015 A look at the forthcoming remake of Point Break | DIY PREVIEW: A LOOK AT THE FORTHCOMING REMAKE OF POINT BREAK This week, DIY were among the very first people in the world to see footage from the upcoming Point Break. By Christa Ktorides on 27th October 2015 This week, DIY were among the very first people in the world to see footage from the upcoming Point Break, the highly anticipated remake of the http://diymag.com/2015/10/27/a-look-at-the-forthcoming-remake-of-point-break 1/6 10/28/2015 A look at the forthcoming remake of Point Break | DIY 1991 action classic courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Screening in the rather luxurious new Picturehouse Central in London, we’re treated to some extended scenes of the unfinished film in the company of director Ericson Core, star Édgar Ramírez and renowned extreme athletes Xavier De Le Rue and Chris Sharma. So why re-make the cult film now? Core explains: “Pretty much every one of our extreme athletes who participated in the film came to it because they were highly influenced by the original film and pursued their various sports partially charged with that sort of spirit of that original film. Ramírez for his part reveals a long-standing relationship with the original Keanu Reeves/Patrick Swayze starrer: “I belong to the generation of the first one, I was 13 years old when that came out. I was very attracted to the movie, very inspired by it. Little did I know that eventually, a few years later I would be playing Bodhi which was definitely the character I was impressed by.” First up we’re shown the opening sequence of the film where YouTube superstar and extreme motorcross rider, Johnny Utah (Luke Bracey) is performing a seemingly impossible stunt for the cameras with his friend Jeff (Max Thieriot). -

06 SM 9/7 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 7, 2004 Monday Evening September 13, 2004 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Benefactor Monday Night Football: Packers @ Panthers Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Yes Dear Raymond Two Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor Las Vegas TBA Local Tonight Show Conan FOX North Shore Renovate My Family Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Parole Squad Plots Gotti Airline Airline Crossing Jordan Parole Squad AMC The Blues Brothers Tough Guys Date With ANIM Growing Up Oranguta That's My Baby Animal Cops Houston Growing Up Oranguta That's My Baby CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage Norton TV DISN Disney Movie: TBA Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS E!ES Dr. 90210 Howard Stern SNL ESPN Monday Night Countdown World Series of Poker Sportscenter ESPN2 Poker Kurt Brow UCA College Cheerleading Who's #1 FAM Great Outdoors Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX Point Break Fear Factor Point Break HGTV Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce Organize Dsgn Chal Dsgn Dim Dsgn Dme To Go Hunters Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce HIST Civil War Combat Civil War Combat Quarries Tactical To Practical Civil War Combat LIFE It Had To Be You IDo(But I Don't) How Clea Golden Nanny Nanny MTV MTV Special Road Rules The Osbo Real World Video Clash Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate SG-1 Stargate -

Kellett to Arrive with Procession

Call (906) 932-4449 Ironwood, MI This Is My Crew Volleyball Soto lifts Nats to 4-3 comeback Mercer beats archrival Redsautosales.com wild-card win over Brewers Washburn SPORTS • 9 SPORTS • 9 DAILY GLOBE Wednesday, October 2, 2019 Few showers yourdailyglobe.com | High: 48 | Low: 40 | Details, page 2 WWII POW COMING HOME Schools Kellett to arrive celebrate with procession homecoming By TOM LAVENTURE Funeral Honors Team, said [email protected] members from the Upper week IRONWOOD – Members of Peninsula who train with the By TOM LAVENTURE the Wisconsin and Michigan team will take part in both the [email protected] Patriot Guard Riders will escort ceremony to receive the IRONWOOD – Area schools the funeral coach with the remains on Thursday, and for are celebrating homecoming this remains of a POW/MIA soldier the funeral home service Satur- week with parades, dress-up from World War II to Ironwood day, and the burial service fol- days and activities all leading up on Thursday. lowing at Riverside Cemetery. to the big games on Friday. “We will have the Patriot “There will be full military The Gogebic Miners, a triad Guard coming on Thursday,” honors provided,” Larson said. football team of Ironwood, Besse- said Michael Patrick, director of John Curran, the Wisconsin mer and Wakefield-Marenisco McKevitt-Patrick Funeral State Captain, said the family school districts, has Luther L. Home, Inc., who is handling has expressed that the Patriot Wright hosting home games this arrangements on behalf of the Guard escort would be wel- year to include the homecoming family of Walter Kellett, a come. -

Hurt Locker Study Notes

The Hurt Locker Study Notes Directed by: Kathryn Bigelow Certificate: 15 Running time: 126 mins Release date: 28 August 2009 Synopsis An intense action thriller set in Iraq, The Hurt Locker concerns the actions of three soldiers responsible for one of the most dangerous and unpredictable jobs in war: bomb disposal. Sergeant Sanborn and Specialist Eldridge are under intense pressure to make the area safer for civilians and their fellow soldiers, but when Sergeant James arrives to take charge of their unit, the three find themselves split because of their radically different approaches to combat. While Sanborn and Eldridge are ‘by-the-book’, James reveals himself to be a renegade who puts the thrilling adrenaline rush of bomb disposal before the safety of his colleagues. On top of this, the soldiers are thrown into increasingly dangerous situations where anything, or anyone, could be a bomb. www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2010. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites. Before Viewing Director Kathryn Bigelow is renowned for making action-packed thrillers that are big and glossy. Issues of gender and identity underpin many of her films and aside from The Hurt Locker, Point Break is probably her most famous film. Like The Hurt Locker, Point Break features characters that put themselves in mortal danger in order to experience an adrenaline rush (in the case of Point Break, bank robbers who risk their lives and freedom in order to fund their skydiving and surfing lifestyles). I Watch a trailer or sequence from Point Break. How does Bigelow represent men? I How might these representations be different if the film were directed by a male? I Now watch the trailer for The Hurt Locker . -

Point Break Pb Ita Def

presenta di Ericson Core con Edgar Ramirez, Luke Bracey, Teresa Palmer, Delroy Lindo e Ray Winstone AL CINEMA DAL 27 GENNAIO Durata: 114 minuti I materiali sono scaricabili dall’area stampa di www.eaglepictures.com Ufficio stampa film Ufficio stampa Eagle Pictures Ornato Comunicazione Via Flaminia, 954 [email protected] 00191 Roma Tel. + 39 06.3341017 + 39 06.33213374 [email protected] 2 CAST TECNICO Diretto da Ericson Core Sceneggiatura di Kurt Wimmer Storia di Rick King Peter Iliff Kurt Wimmer Produttori Andrew A. Kosove Broderick Johnson John Baldecchi David Valdes Christopher Taylor Kurt Wimmer Produttori Esecutivi Robert L. Levy Peter Abrams Dan Mintz Wu Bing John McMurrick Direttore della fotografia Ericson Core Scenografia Udo Kramer Montaggio Thom Noble Jerry Greenberg, A.C.E. John Duffy, A.C.E. Costumi Lisy Christl Musiche Tom Holkenborg Casting John Papsidera, CSA 3 CAST ARTISTICO BODHI Edgar Ramirez UTAH Luke Bracey SAMSARA Teresa Palmer PAPPAS Ray Winstone ISTRUTTORE HALL Delroy Lindo GROMMET Matias Varela ROACH Clemens Schick CHOWDER Tobias Santelmann SURFISTA VAGABONDO Laird Hamilton CAMEO FESTA YACHT Bob Burnquist Faris Al-Sultan Sal Masekela Seth Troxler CAMEO FESTA CHALET Steve Aoki Jeb Corliss Xavier De Le Rue Chris Sharma 4 In POINT BREAK, action thriller concentrato di pura adrenalina della Alcon Entertainment, Johnny Utah (Luke Bracey, che vedremo prossimamente in “Hacksaw Ridge” di Mel Gibson), giovane agente dell’FBI, s’infiltra in un gruppo itinerante di atleti amanti del brivido, capeggiati dal carismatico Bodhi (Edgar Ramirez, che vedremo prossimamente in “Joy” di David O. Russell). Gli atleti sono sospettati di crimini perpetrati in maniera estremamente inusuale. -

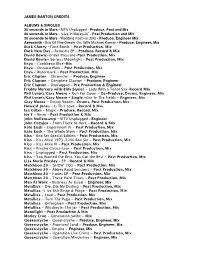

Jb-Website Credits

JAMES BARTON CREDITS ALBUMS & SINGLES 30 seconds to Mars - MTV Unplugged - Produce, Post and Mix 30 seconds to Mars - “Live In Malaysia” - Post Production and Mix 30 seconds to Mars -“Redding Festival (UK) - Produce, Engineer Mix Aerosmith - Box Of Fire-Dream On, With Michael Kaman - Produce, Engineer, Mix Buck Cherry -Time Bomb - Post Production, Mix Dark New Day – Acoustic EP – Produce, Record & Mix David Bowie-Under Pressure-Post Production, Mix David Bowie- Serious Moonlight – Post Production, Mix Enya - Caribbean Blue-Mix Enya - Orinoco Flow - Post Production, Mix Enya – Watermark - Post Production, Mix Eric Clapton – Chronicles - Produce, Engineer Eric Clapton - Complete Clapton - Produce, Engineer Eric Clapton – Unplugged - Pre Production & Engineer Freddy Mercury with Billy Squier - Lady With a Tenor Sax-Record Mix Phil Lynott/Gary Moore - Run For Cover – Co-Produce, Drums, Engineer, Mix Phil Lynott/Gary Moore – Single -Out In The Fields - Engineer, Mix Gray Moore - Empty Rooms- Drums, Post Production, Mix Howard Jones – Is This Love – Record & Mix Ian Gillan – Magic – Produce, Record, Mix Ice T – 9mm – Post Production & Mix John Mellencamp - MTV Unplugged - Engineer John Oszajca - From There to Here – Record & Mix Kate Bush - Experiment IV - Post Production, Mix Kate Bush - The Whole Story - Post Production, Mix Kiss - Box Set Special Edition – Post Production, Mix Kiss - Kiss Alive 1975-2000 Box Set - Post Production, Mix Kiss - Kiss Alive III - Post Production, Mix Kiss - Psycho Circus-Live - Post Production, Mix Kiss – Unplugged -

Christina Lane: Feminist Hollywood. from Born in Flames to Point Break Detroit: Waync Statt: Unin:Rsity Press 2000

Forog1·<1/ie 1111d Fi/111 Christina Lane: Feminist Hollywood. From Born in Flames to Point Break Detroit: Waync Statt: Unin:rsity Press 2000. 261 S .. ISBN 0-8 l--U-2922-5. S 19.95 lt rnust be frustrating that the only example of a publicly recognisable fernale auteur Christina Lane has to offer is Kathryn Bigelow \\ ho has not only col laborated closely with Hollywood .überrnensch· \\illiarn Cameron but was in fact marricd to him. To further muddy thc idcological ,, atcrs. Bigelm, ·s ]ist of favourite dircctors includes Sam Peckinpah. \\/alter I-!ill. Oliwr Sterne and Martin Scorscse, male directors not oftcn idcntificd \\'ith \\OI11e11's issues or feminist politics. Finding female directors. feminist auteur or othcrn ise. in an industry which has permitted only fifteen mainstream films to bc directcd by \\Omen bet,,een 1949 and 1979. is to say the least. diffieult. As Lane points out. perhaps Bigelow·s publ ic rccognition stcms rnore frnm thc male cstahlishmenrs appreciation of her good looks and their inability to sec thc challenges to their .natura]· position in society inherent 111 her rc-workings of genre films. Thc issuc of autcurisrn is only one of rnany discussed in Lane·s study of fcminist dircctors ,,orking in conternporary Amcrican cinema. By analysing the carccr trajectorics of six eontemporary directors: Sföan Seidel man. lvlartha Coo lidgc. Kathryn Bigclow. Lizzie Bordcn. Darnell Martin and Tamra Dm ies. Lane interrogates thc currcnt intcr-rclatiL1nship bernccn countcr einema and mainstream film. Through carcful textual analysis ofthcir \\Ork iföide and outsidc thc system. shc dernonstratcs ho\\' thc dominant cincmatic codes of th1: former ha, c bccn challcnged by thc feminist a\ ant-garde real ist ideologies of th1: latter.