Bigelow Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zero Dark Thirty Error

Issue 7 | Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism | 23 troop carrier with no clear sense of destination, speaks again understated performances further serve to create what might as much to a national as a personal loss of purpose, afer the be described as a reality afect. quest is over. Te 9/11 sequence ofers an extreme version of the real- Te flm’s epilogue has received considerable critical atten- ist aesthetic and the rejection of spectacle. From the second tion1; the prologue less so. And where critics do mention it, plane hitting the tower, to the falling man, to the rubble details are ofen misremembered. In an interview with Kyle of ground zero, there are any number of iconic images the Buchanan, screenwriter Mark Boal refects on the difculties flmmakers might have selected to represent the destruction of writing the ‘opening scene’ of Zero Dark Tirty (2013). Te wrought by the attacks. However, what such images have in scene he is referring to in this discussion, however, is the infa- common, what potentially makes them efective as a form of mous torture scene that begins the narrative proper (to which cultural shorthand, also renders them problematic in terms I will return). It is as if he has momentarily forgotten the scene of eliciting a fresh response – and certainly in terms of the Intimacy, ‘truth’ and the gaze: that precedes it in the original shooting script as well as the slow-burn, reality afect. Teir very familiarity can render flm. Given this oversight by the writer himself, it is under- such images hackneyed and over-determined. -

Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The Hurt Locker"

Cinesthesia Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 12-1-2012 Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The urH t Locker" Kelly Meyer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Kelly (2012) "Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The urH t Locker"," Cinesthesia: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol1/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meyer: Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The Hurt Locker" Cinematic Realism in Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker No one has ever seen Baghdad. At least not like explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) squad leader William James has, through a lens of intense adrenaline and deathly focus. In the 2008 film The Hurt Locker, director Katherine Bigelow creates a striking realist portrait of an EOD team on their tour of Baghdad. Bigelow’s use of deep focus and wide- angle shots in The Hurt Locker exemplify the realist concerns of French film theorist André Bazin. Early film theory has its basis in one major goal: to define film as art in its own right. In What is Film Theory, authors Richard Rushton and Gary Bettinson state that “…each theoretical inquiry converges on a common objective: to defend film as a distinctive and authentic mode of art” (8). Many theorists argue relevant and important points regarding film, some from a formative point of view and others from a realist view. -

Film & Literature

Name_____________________ Date__________________ Film & Literature Mr. Corbo Film & Literature “Underneath their surfaces, all movies, even the most blatantly commercial ones, contain layers of complexity and meaning that can be studied, analyzed and appreciated.” --Richard Barsam, Looking at Movies Curriculum Outline Form and Function: To equip students, by raising their awareness of the development and complexities of the cinema, to read and write about films as trained and informed viewers. From this base, students can progress to a deeper understanding of film and the proper in-depth study of cinema. By the end of this course, you will have a deeper sense of the major components of film form and function and also an understanding of the “language” of film. You will write essays which will discuss and analyze several of the films we will study using accurate vocabulary and language relating to cinematic methods and techniques. Just as an author uses literary devices to convey ideas in a story or novel, filmmakers use specific techniques to present their ideas on screen in the world of the film. Tentative Film List: The Godfather (dir: Francis Ford Coppola); Rushmore (dir: Wes Anderson); Do the Right Thing (dir: Spike Lee); The Dark Knight (dir: Christopher Nolan); Psycho (dir: Alfred Hitchcock); The Graduate (dir: Mike Nichols); Office Space (dir: Mike Judge); Donnie Darko (dir: Richard Kelly); The Hurt Locker (dir: Kathryn Bigelow); The Ice Storm (dir: Ang Lee); Bicycle Thives (dir: Vittorio di Sica); On the Waterfront (dir: Elia Kazan); Traffic (dir: Steven Soderbergh); Batman (dir: Tim Burton); GoodFellas (dir: Martin Scorsese); Mean Girls (dir: Mark Waters); Pulp Fiction (dir: Quentin Tarantino); The Silence of the Lambs (dir: Jonathan Demme); The Third Man (dir: Carol Reed); The Lord of the Rings trilogy (dir: Peter Jackson); The Wizard of Oz (dir: Victor Fleming); Edward Scissorhands (dir: Tim Burton); Raiders of the Lost Ark (dir: Steven Spielberg); Star Wars trilogy (dirs: George Lucas, et. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

The “Genre Bender”: the Creative Leadership of Kathryn Bigelow

THE “GENRE BENDER”: THE CREATIVE LEADERSHIP OF KATHRYN BIGELOW Olga Epitropaki and Charalampos Mainemelis ABSTRACT In the present chapter, we present the case study of the only woman film director who has ever won an Academy Award for Best Director, Kathryn Bigelow. We analyzed 43 written interviews of Kathryn Bigelow that have appeared in the popular press in the period 1988 2013 and outlined eight main themes emerging regarding her exercise ofÀ leadership in the cinematic context. We utilize three theoretical frameworks: (a) paradoxical leadership theory (Lewis, Andriopoulos, & Smith, 2014; Smith & Lewis, 2012); (b) ambidextrous leadership theory (Rosing, Frese, & Bausch, 2011), and (c) role congruity theory (Eagley & Karau, 2002) and show how Bigelow, as a woman artist/leader working in a complex organizational system that emphasizes radical innovation, exercised paradoxical and ambidextrous leadership and challenged Downloaded by Doctor Charalampos Mainemelis At 07:19 09 March 2016 (PT) Leadership Lessons from Compelling Contexts Monographs in Leadership and Management, Volume 8, 275 300 À Copyright r 2016 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 1479-3571/doi:10.1108/S1479-357120160000008009 275 276 OLGA EPITROPAKI AND CHARALAMPOS MAINEMELIS existing conventions about genre, gender, and leadership. The case study implications for teaching and practice are discussed. Keywords: Creative leadership; ambidextrous leadership; paradoxical leadership; role congruity theory; director; film industry She’s acting out desires. She represents what people want to see, and it’s upsetting, because they don’t know exactly what to do with it. Cultural theorist Sylve´ re Lotringer INTRODUCTION Organizations are abounding with tensions and conflicting demands (e.g., flexibility vs. -

Blurring the Boundaries: Auteurism & Kathryn Bigelow Brenda Wilson

Blurring the Boundaries: Auteurism & Kathryn Bigelow Brenda Wilson Born in California in 1952, Katherine Bigelow is one of group of outsiders living by different rules are presented the few women directors working in Hollywood today. She here as whole- heartedly cool. And the aesthetic style of is exceptional because she works primarily within the the film is indicative of Bigelow's increasingly idiosyncratic traditionally male- dominated genres of the action cinema. choices that create arresting images and innovative action Bigelow's films often reflect a different approach to these sequences. Strange Days (1995) is the film in Bigelow's genres as she consistently explores themes of violence, oeuvre that has received the most critical and theoretical voyeurism and sexual politics. Ultimately she seems to be attention, and so for the purposes of this analysis it will be concerned with calling the boundaries between particular referred to but not fully theorized. Strange Days is a neo- genres into question. Bigelow's visual style echoes this noir science fiction film that presents the future on the eve thematic complexity, often introducing elements of an art- of the new millennium, a dystopic Los Angeles which is on house aesthetic. Bigelow emerged from the New York art the verge of erupting into a race war. The film was a critical scene in the 1970s, having won a Whitney Scholarship to if not commercial success, building upon recognizable study painting. She later transferred to the Columbia Film Bigelow motifs. The film is a rich tapestry of narrative program. Critics such as Yvonne Tasker have commented threads, stunning visuals and soundtrack, all of which on the amalgamation of spectacle and adrenaline with compete for attention. -

April 14 2019

APRIL 5 - APRIL 14 SPONSORSHIP 2019 323 Central Ave | Sarasota, FL 34236 | www.sarasotafilmfestival.com | 941.364.9514 A 501(C)(3) Non Profit Organization The Sarasota Film Festival is a ten-day celebration of the art of filmmaking and the contribution that film makes to our culture. Celebrating 21 years and beyond, SFF has an esteemed reputation as a destination festival while providing a platform for filmmakers in all stages of their careers locally, nationally, and globally. 2018 Sarasota Film Festival 14 56 43 124 World Documentary Narrative Shorts Premieres Features Features 2 MEET OUR ATTENDEES 3 About our Attendees SFF patrons are well educated, brand savvy, sponsor friendly and have high disposable income. With a satisfaction rating over 90%, our audiences are loyal and engaged throughout the Festival. • Physical Attendance 50,000 + patrons • 80% live in Sarasota year-round • 20% make over $200,000/year • 47% own two or more homes • 55% make $100k/year with average income of • 72% earn more than double the median $122,000 income of other Florida residents • 91% have bachelor’s degree or above • 55% regular retail shoppers • 26% Male • 40% drive a luxury vehicle • 73% Female 4 Social, Digital, and Traditional Media Impressions • Social Media delivers 3+ million impressions annually • IMDb partnership delivers 3+ million impressions • Television advertising delivers 2+ million impressions • Film guide reaches 250k+ viewers • Website delivers 1+ million impressions • Email list of 10k+ patrons • On-screen theatrical branding reaches 50k+ patrons • Press outlets include Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, IndieWire, and IMDb 5 FILM REPRESENTATION 6 Sarasota Film Festival programmers find the best in indie cinema to present a diverse array of domestic, foreign, and studio films that receive critical acclaim, national and international awards consideration. -

A Look at the Forthcoming Remake of Point Break | DIY

10/28/2015 A look at the forthcoming remake of Point Break | DIY PREVIEW: A LOOK AT THE FORTHCOMING REMAKE OF POINT BREAK This week, DIY were among the very first people in the world to see footage from the upcoming Point Break. By Christa Ktorides on 27th October 2015 This week, DIY were among the very first people in the world to see footage from the upcoming Point Break, the highly anticipated remake of the http://diymag.com/2015/10/27/a-look-at-the-forthcoming-remake-of-point-break 1/6 10/28/2015 A look at the forthcoming remake of Point Break | DIY 1991 action classic courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Screening in the rather luxurious new Picturehouse Central in London, we’re treated to some extended scenes of the unfinished film in the company of director Ericson Core, star Édgar Ramírez and renowned extreme athletes Xavier De Le Rue and Chris Sharma. So why re-make the cult film now? Core explains: “Pretty much every one of our extreme athletes who participated in the film came to it because they were highly influenced by the original film and pursued their various sports partially charged with that sort of spirit of that original film. Ramírez for his part reveals a long-standing relationship with the original Keanu Reeves/Patrick Swayze starrer: “I belong to the generation of the first one, I was 13 years old when that came out. I was very attracted to the movie, very inspired by it. Little did I know that eventually, a few years later I would be playing Bodhi which was definitely the character I was impressed by.” First up we’re shown the opening sequence of the film where YouTube superstar and extreme motorcross rider, Johnny Utah (Luke Bracey) is performing a seemingly impossible stunt for the cameras with his friend Jeff (Max Thieriot). -

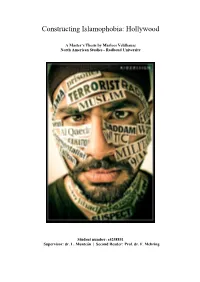

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood A Master’s Thesis by Marloes Veldhausz North American Studies - Radboud University Student number: s4258851 Supervisor: dr. L. Munteán | Second Reader: Prof. dr. F. Mehring Veldhausz 4258851/2 Abstract Islam has become highly politicized post-9/11, the Islamophobia that has followed has been spread throughout the news media and Hollywood in particular. By using theories based on stereotypes, Othering, and Orientalism and a methodology based on film studies, in particular mise-en-scène, the way in which Islamophobia has been constructed in three case studies has been examined. These case studies are the following three Hollywood movies: The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, and American Sniper. Derogatory rhetoric and mise-en-scène aspects proved to be shaping Islamophobia. The movies focus on events that happened post- 9/11 and the ideological markers that trigger Islamophobia in these movies are thus related to the opinions on Islam that have become widespread throughout Hollywood and the media since; examples being that Muslims are non-compatible with Western societies, savages, evil, and terrorists. Keywords: Islam, Muslim, Arab, Islamophobia, Religion, Mass Media, Movies, Hollywood, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, American Sniper, Mise-en-scène, Film Studies, American Studies. 2 Veldhausz 4258851/3 To my grandparents, I can never thank you enough for introducing me to Harry Potter and thus bringing magic into my life. 3 Veldhausz 4258851/4 Acknowledgements Thank you, first and foremost, to dr. László Munteán, for guiding me throughout the process of writing the largest piece of research I have ever written. I would not have been able to complete this daunting task without your help, ideas, patience, and guidance. -

American Myth-Busting

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship & Creative Works 2012 American Myth-Busting Joe Wilkins Linfield College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englfac_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons DigitalCommons@Linfield Citation Wilkins, Joe, "American Myth-Busting" (2012). Faculty Publications. Published Version. Submission 17. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englfac_pubs/17 This Published Version is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Published Version must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. MEDIA THE ARTS much sway in our contemporary cul- American Myth-Busting tural psyche, consider instead Rambo, or A the latest iteration of Die Hard, or even new breed ofwesterns tells it like it is The Hurt Locker- really any big-screen BY JOE WILKINS affair featuring an honorable, lonely, de- cidedly masculine hero staring down the bad guys. Truly, many of the shoot' em-up GROWING UP ON THE PLAINS of eastern history ofcivilization , the event which in blockbusters we see each summer are di- Montana, I saw my fair share of westerns. spite of stupendous difficulties was con- rect mythological descendants of those We didn't have a VCR when I was a boy, and summated more swiftly, more completely, dime-novel westerns, which posited that, my mother didn't allow us to watch much more satisfactorily than any like event with right intention, violence will lead to TV, but westerns were part ofthe general at- since the westward migration began-I stability and community; that the present mosphere. -

Creative Industries: Behind the Scenes Inequalities

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Theses Department of Sociology Fall 12-17-2019 CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: BEHIND THE SCENES INEQUALITIES Sierra C. Nicely Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses Recommended Citation Nicely, Sierra C., "CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: BEHIND THE SCENES INEQUALITIES." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses/86 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: BEHIND THE SCENES INEQUALITIES by SIERRA NICELY Under the Direction of Wendy Simonds, PhD ABSTRACT Film has been a major influence since its creation in the early 20th century. Women have always been involved in the creation of film as a cultural product. However, they have rarely been given positions of power in major film productions. Using qualitative approaches, I examine the different ways in which men and women directors approach creating film. I examine 20 films, half were directed by men and half by women. I selected the twenty films out of two movie genres: Action and Romantic Comedy. These genres were chosen because of their very gendered marketing. My focus was on the different ways in which gender was shown on screen and the differences in approach by men and women directors. The research showed differences in approach of gender but also different approaches in race and sexuality. Future studies should include more analysis on differences by race and sexuality. -

06 SM 9/7 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 7, 2004 Monday Evening September 13, 2004 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Benefactor Monday Night Football: Packers @ Panthers Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Yes Dear Raymond Two Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor Las Vegas TBA Local Tonight Show Conan FOX North Shore Renovate My Family Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Parole Squad Plots Gotti Airline Airline Crossing Jordan Parole Squad AMC The Blues Brothers Tough Guys Date With ANIM Growing Up Oranguta That's My Baby Animal Cops Houston Growing Up Oranguta That's My Baby CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage Norton TV DISN Disney Movie: TBA Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS E!ES Dr. 90210 Howard Stern SNL ESPN Monday Night Countdown World Series of Poker Sportscenter ESPN2 Poker Kurt Brow UCA College Cheerleading Who's #1 FAM Great Outdoors Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX Point Break Fear Factor Point Break HGTV Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce Organize Dsgn Chal Dsgn Dim Dsgn Dme To Go Hunters Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce HIST Civil War Combat Civil War Combat Quarries Tactical To Practical Civil War Combat LIFE It Had To Be You IDo(But I Don't) How Clea Golden Nanny Nanny MTV MTV Special Road Rules The Osbo Real World Video Clash Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate SG-1 Stargate